Chapter 7

Supportive Periodontal Care

Aims

To provide a comprehensive overview of those aspects of supportive periodontal care (SPC) that follow successful non-surgical management and which are essential to long-term periodontal stability and health.

Outcome

After studying this chapter, the reader should:

-

understand what is meant by supportive periodontal care (formerly called periodontal “maintenance”)

-

appreciate the goals of SPC and how they might be achieved

-

appreciate the need for patient compliance

-

understand how poor compliance is identified and improved.

Definitions

SPC can be categorised as either primary or secondary.

Primary SPC is essentially preventive and population-based. The aim is to deliver cost-effective dental healthcare measures through community education programmes to limit the development of gingivitis and, in the longer term, to prevent the progression of gingivitis to periodontitis.

Secondary SPC necessitates intervention and may be palliative or directed at the maintenance of post-treatment stability. The aim of palliative SPC is to limit or slow down the rate of progression of disease in those individuals who are unable to achieve adequate levels of plaque control. This may be because of poor motivation and poor compliance, or because the patient is medically compromised and unable to undertake effective toothbrushing on a regular basis. In such cases, the removal of plaque and calculus at regular recall visits might help to increase the longevity of a functional dentition.

The aim of post-treatment SPC is to maintain the successful outcomes of periodontal treatment and to prevent, or minimise the chance of, disease recurrence. Post-treatment SPC should be the natural extension of periodontal treatment, but may also involve re-treatment of those sites that have failed to respond. This chapter deals with those aspects of SPC that are relevant to maintaining post-treatment stability following non-surgical periodontal management.

The Rationale for Supportive Periodontal Care

In the 1970s and 1980s a series of classic, longitudinal studies were carried out to assess the efficacy of SPC in patients with advanced periodontitis and who had received surgical or non-surgical therapy. The results of these studies showed that over periods of up to six years, those patients who were recalled on a regular basis for professional prophylaxis, removal of reformed deposits, reinforcement of toothbrushing and the use of interdental cleaning aids were able to maintain:

-

excellent standards of oral hygiene

-

healthy gingival tissues

-

shallow, post-treatment periodontal pockets

-

unaltered attachment levels

-

an intact dentition.

Those patients who were not enrolled in an effective SPC programme demonstrated:

-

frank gingivitis

-

deepening of pockets

-

continued loss of attachment

-

tooth loss.

In the 1980s, it became apparent that the progression of periodontitis on a patient level did not conform to a linear pattern with time but appeared to follow a more random pattern in which periods of active disease were interspersed with periods of inactivity. If the initial treatment phase is inadequate or if some risk factors are not identified then this pattern of disease progression may persist but it will become evident during SPC and re-treatment can then be arranged.

Fortunately, most patients who comply with a SPC programme will achieve periodontal stability, although this can never be guaranteed. Studies during the 1990s confirmed that a few individuals show continued attachment loss despite the very best efforts of the dental team and regular recall visits for SPC. Affected sites tend to show a more predictable and linear pattern of disease progression and it must also be remembered that, although SPC might be considered palliative for such patients, any disease progression is likely to be much slower with SPC than without.

The Goals of Supportive Periodontal Care

The ultimate goal of attaining a disease-free mouth is commendable but is neither realistic nor practical for many patients. The three therapeutic goals of SPC that were identified in a position paper of the American Academy of Periodontology in 1998 accept that SPC should be directed towards limiting disease progression, identifying those sites that continue to break down and providing additional treatment when indicated. The goals are:

-

to prevent or minimise the recurrence and progression of periodontal disease in patients who have been previously treated for gingivitis, peri-odontitis and peri-implantitis

-

to prevent or reduce the incidence of tooth loss by monitoring the dentition and any prosthetic replacements for the natural teeth

-

to increase the chance of locating and treating, in a timely manner, other diseases or conditions found within the oral cavity.

Clearly, the first objective is achieved by maintaining optimal supra- and subgingival plaque control together with the regular removal of reformed deposits of calculus. However, any programme of SPC must be designed to meet the needs of the individual patient and will, therefore, almost always require a more wide-ranging consideration of the patient’s ongoing dental care.

Components of Supportive Periodontal Care

A visit for SPC may include any or all of the following components:

-

medical, dental and social histories

-

clinical examination and updating records

-

radiographic examination

-

communication

-

reinforcement of plaque control

-

continued support with smoking cessation

-

supragingival prophylaxis

-

subgingival instrumentation.

Medical, Dental and Social Histories

Histories should be updated regularly to confirm the presence of persistent risk factors and to identify new risk factors for periodontal disease. This might include recording a change in smoking status, an alteration of glycaemic control in a diabetic patient, or possibly identifying the development of stress.

Clinical Examination and Updating Records

The periodontal examination will provide data that should be compared directly either to the pre-treatment measurements or to clinical measurements made after treatment has been completed:

-

a formal assessment of the patient’s oral hygiene status

-

probing depths

-

clinical attachment levels including the extent of gingival recession

-

furcation involvement

-

presence or absence of bleeding on probing (BoP)

-

presence or absence of suppuration on probing

-

tooth or implant mobility.

The assessment of plaque control should be made at every visit for SPC as this will help to inform the need for reinforcement of toothbrushing measures. The amount of plaque on the teeth tells us very little, if anything, about the disease status of the patient. Nevertheless, the compliance and motivation of those patients who attend for SPC with gross deposits of supragingival plaque might be questioned.

The remaining measurements should be made according to a predetermined time schedule (e.g. at six and 12 months, and then at 12-month intervals thereafter). There is an argument, however, for not probing those sites, which, on usual inspection, appear to have minimal plaque deposits and only superficial gingival inflammation. Sites heal by the formation of a long junctional epithelium and it is important, particularly during the first few months after treatment, that this structure is allowed to adapt tightly to the root surface rather than being persistently traumatised by repeated periodontal probing.

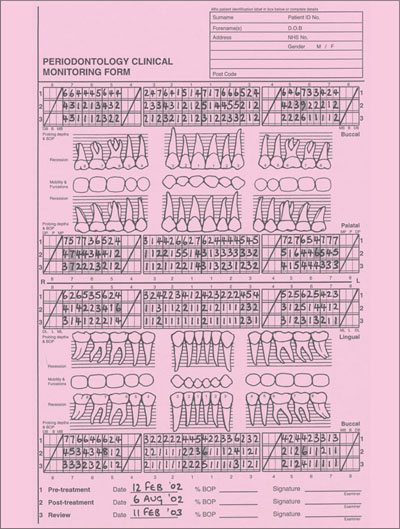

The recording of probing depths and attachment levels are operator sensitive and may show considerable variation, even for the same operator making measurements using the same periodontal probe but on different occasions. This means that a decision has to be made whether a “deterioration” or “improvement” in probing depth is actually a real change or simply a manifestation of intra-operator variability. If a probe with 1mm gradations is used to record probing depths and attachment levels, it is helpful to set a threshold of 2mm, so that a change of 2mm or more from pre-treatment denotes an actual change, whereas a “change” of only 1mm could possibly be due to operator variability. These “changes” can then be highlighted on the patient’s periodontal chart (Fig 7-1).

Fig 7-1 Chart showing probing depth measurements pre-treatment and six and 12 months following treatment. If a threshold or cut-off of 2mm is assumed to reflect real change then a useful technique is to highlight those sites that are deteriorating and those that are improving. The deteriorating sites are then selected for retreatment.

BoP to the depth of a periodontal pocket has, traditionally, been taken to be an indication of an “active” periodontal site that is undergoing attachment loss (Fig 7-2). Research in the 1990s has determined that only about 30% of those sites that continue to bleed on consecutive visits actually demonstrate additional loss of attachment, thus sug/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses