Mycotic Infections of the Oral Cavity

Mycology, the study of fungal infections, has gained remarkable impetus in the past few decades, owing at least in part to the fact that fungal diseases are far more common than was previously suspected. Many erroneous conceptions of this branch of microbiology existed until only recently, but careful scientific investigation of various aspects of mycology, such as epidemiology, pathogenesis, immunology, diagnosis and treatment, has done much to eliminate the confusion. Furthermore, excellent monographs and reviews on certain fungal diseases, such as those on blastomycosis by Witorsch and Utz and by Sarosi and Davies; on coccidioidomycosis by Fiese and by Stevens; on cryptococcosis by Littman and Zimmerman; on histoplasmosis by Sweany and by Goodwin and his colleagues; and on mucormycosis (phycomycosis) by Lehner, have been valuable contributions to our understanding of these conditions.

North American Blastomycosis: (Gilchrist’s disease)

Clinical Features

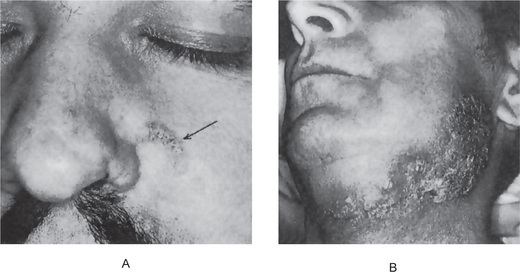

North American blastomycosis is far more common in men than in women and typically occurs in middle age. Skin lesions usually begin as small red papules which gradually increase in size and form tiny miliary abscesses or pustules which may ulcerate to discharge the pus through a tiny sinus. Crateriform lesions are typical and these often exhibit indurated and elevated borders (Figs. 7-1, 7-2). The infection commonly spreads through the subcutaneous tissues and becomes disseminated through the blood stream. The systemic disease is characterized by fever, sudden weight loss, and in cases of lung involvement, a productive cough associated with other symptoms typical of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Oral Manifestations

Lesions of the oral cavity have been reported occurring in blastomycosis and may resemble those of actinomycosis, although abscess formation is not usually as prominent. Tiny ulcers may be the chief feature. The oral infection may be either the primary lesion or secondary to lesions elsewhere in the body. In an extensive discussion of this disease, Witorsch and Utz have reported that 25% of their group of patients had oral or nasal mucosal lesions. Bell and his coworkers have also pointed out that the oral lesions, which may be the first apparent manifestation of the disease, are probably more common than has been thought. In two cases reported by Page and his associates, the oral lesions bore enough resemblance to epidermoid carcinoma to warrant it as a consideration in the differential diagnosis.

Histologic Features

The microscopic features of North American blastomycosis are similar to those of other chronic granulomatous infections. The inflamed connective tissue shows occasional giant cells and macrophages and the typical round organisms, often budding, which appear to have a doubly refractile capsule (Fig. 7-2). The organisms, usually measuring between 5μ and 15μ in diameter, are common within giant cells. Microabscesses are frequently found. If the lesions are not ulcerated, overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be prominent.

South American Blastomycosis: (Lutz’s disease, Paracoccidioidomycosis)

Oral Manifestations

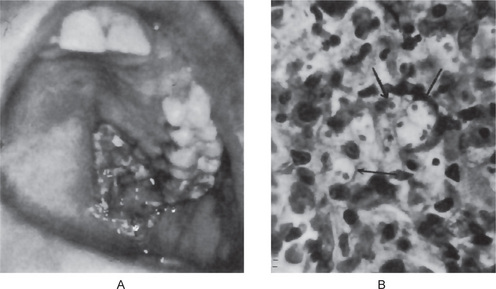

Bogliolo reported that the organisms may enter the body through the periodontal tissues and subsequently reach the regional lymph nodes, producing a severe lymphadenopathy. He has demonstrated the organisms in both the periodontal membrane and in a periapical granuloma and has cultivated them from these sites. The microorganisms also have been shown to penetrate the tissues and establish infection after extraction of teeth, producing papillary lesions of the oral mucosa. Widespread oral ulceration is also a common finding.

Histoplasmosis: (Darling’s disease)

Oral Manifestations

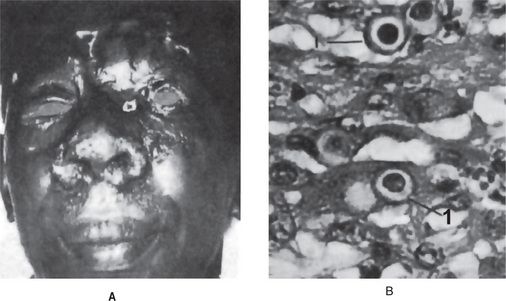

The oral lesions of histoplasmosis have been reviewed by Levy and by Stiff. They appear as nodular, ulcerative or vegetative lesions on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, palate, or lips (Fig. 7-3). The ulcerated areas are usually covered by a nonspecific gray membrane which is indurated with raised and rolled out borders resembling carcinoma. The organisms may be demonstrated in tissue sections in many, but not all cases. Thus it is wise in suspected cases to preserve a piece of tissue at the time of biopsy for microbiologic examination. The organism may be readily isolated by inoculating the emulsified tissue onto blood agar containing penicillin and streptomycin. Occasionally cases have been mistaken for carcinoma or even Vincent’s infection, while the lymphadenopathy has suggested Hodgkin’s disease.

Histologic Features

Histoplasmosis appears basically to be a granulomatous infection which affects chiefly the reticuloendothelial system. Thus the organisms are found in large numbers in phagocytic cells and appear as tiny intracellular structures measuring little more than 1μ in diameter (Fig. 7-3).

Coccidioidomycosis: (Valley fever, San Joaquin valley fever)

Oral Manifestations

Lesions of the head and neck, including the oral cavity, occur with some frequency as has been pointed out by Frauenfelder and Schwartz. The lesions of the oral mucosa and skin are proliferative granulomatous and ulcerated lesions that are nonspecific in their clinical appearance. These lesions tend to heal by hyalinization and scar. Marked chronicity is often a feature of these lesions. Lytic lesions of the jaws may also occur and such a case has been reported by Igo and his associates.

Cryptococcosis: (Torulosis, European blastomycosis)

Cryptococcosis is a chronic fungal infection caused by Cryptococcus neoformans (Torula histolytica) and Cryptococcus bacillispora, and may present widespread lesions in the skin, oral mucosa, subcutaneous tissues, lungs, joints, and particularly the meninges. The organisms are widespread and frequently found on the skin of healthy persons; for this reason, the exact mechanism of infection is not known. The organisms appear to be harbored by pigeons, but the actual infection of the human probably results from inhalation of airborne microorganisms. Since it is often an opportunistic infection, the disease has increased in incidence as immunosuppression has become more prevalent.

Oral Manifestations

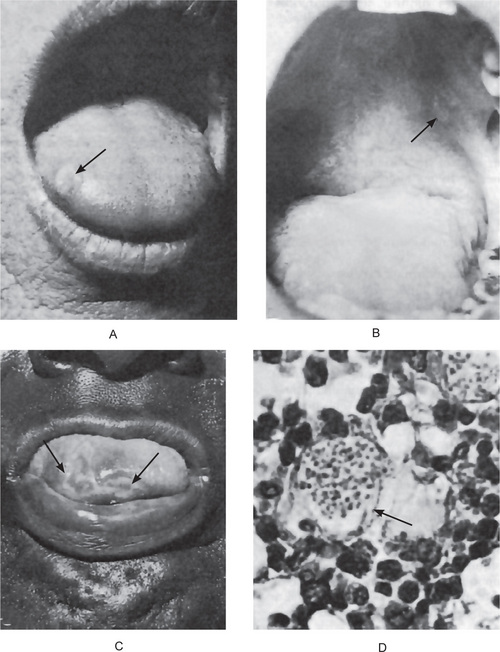

The oral lesions appear as simply nonspecific single or multiple ulcers, which in a patient known to have leukemia, may be mistaken for the widespread ulceration often seen in leukemic patients as a result of their inability to react to a mild, nonspecific bacterial infection (Fig. 7-4A).

Histologic Features

The causative organism is a gram-positive, budding, yeast-like cell with an extremely thick, gelatinous capsule. The Cryptococcus measures 5–20μ in diameter, and in tissue sections, appears as a small organism with a large clear halo, sometimes described as ‘tissue microcyst’ (Fig. 7-4B). The capsule is colored intensely with the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain, and the organisms may be cultured on Sabouraud’s glucose agar.

Candidiasis: (Candidosis, moniliasis, thrush)

It has been shown repeatedly that this microorganism is a relatively common inhabitant of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and vagina of clinically normal persons. When the favorable condition develops, the organism transforms into pathogenic form, that is yeast form transformed into hyphae. Thus it appears that the mere presence of the fungus is not sufficient to produce the disease. There must be actual penetration of the tissues, although such invasion is usually superficial and occurs only under certain circumstances. This disease is said to be the most opportunistic infection in the world. Its occurrence has increased remarkably since the prevalent use of antibiotics, which destroy the normally inhibitory bacterial flora and immunosuppressive drugs, particularly corticosteroids and cytotoxic drugs. This is the chief cause of this disease in patients with leukemia, lymphoma or other tumors. In addition to affecting the oral cavity, monilial infection frequently involves the skin as well as the gastrointestinal tract, vaginal tract, urinary tract, and lungs. Vaginal colonization appears to be increased by diabetes, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive agents. The incidence of oral candidiasis has increased after the advent of human immunodeficiency virus. It is reported that more than 90% of the HIV infected individuals develop oral candidiasis during some part of their disease (Ellepola ANB and Samaranayake LP, 2000). Oral candidiasis, usually remains a localized disease, but on occasion it may show extension to t/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses