Chapter 7

Finishing and Polishing Restorations

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe the armamentarium that can be used to finish and polish different types of restorative material.

Outcome

Readers will gain increased understanding of the best methods of finishing and polishing restorations, as determined by material type, filler particle size and restoration location.

Introduction

Finishing a restoration involves contouring to create optimal marginal finish, without overhangs or excess material extending beyond the cavity margin, and establishing an occlusal anatomy in harmony with the rest of the dentition. Polishing a restoration involves smoothing the surface with a series of abrasives to create the lowest surface roughness and a high surface lustre or polish.

The advantages of finishing and polishing include:

-

minimising plaque accumulation at margins and on surfaces of restorations

-

minimising the risk of surface staining

-

minimising surface degradation and wear in clinical service

-

maximising the aesthetics of the restoration by creating a high lustre or polish

-

enhanced patient and dentist satisfaction

-

reduced likelihood that a dentist will decide to replace the restoration unnecessarily (Oleinisky et al., 1996).

There are, however, some potential disadvantages of excessive finishing and polishing; a notable problem is increased heat generation, which may adversely affect the pulp.

Dental Amalgams

At placement, contouring of the amalgam is carried out using various instruments, according to the clinician’s preference and the specific circumstances. Carving should always be across margins on to adjacent tooth tissue to optimise marginal adaptation. The surface of the carved amalgam should be lightly compacted and smoothed with a burnisher hand instrument. This technique, sometimes referred to as resurfacing, aims to homogenise the amalgam forming the surface of the restoration and to readapt the material to cavity margins – in particular, where it may have been carved away (see Fig 5-14).

The surface of the amalgam may be given a uniform lustre with a damp cotton wool pellet held in tweezers. This procedure aids refinements at a subsequent visit and improves marginal integrity. Excessive manipulation of the surface of a newly placed amalgam should be avoided to prevent gouging or damage to the structure.

At the next appointment, the surface of the amalgam can be refined, if required, using steel finishing burs, with water coolant to avoid overheating and to reduce the amount of mercury vapour released. Steel finishing burs are available in a range of sizes and shapes to aid access to all aspects of the restoration (Fig 7-1).

Fig 7-1 Examples of burs used to polish dental amalgam. Steel finishing burs are shown in the lower part of the picture, and “greenies” and “brownies” – abrasive finishing points – in the upper part.

An exception to the normal protocol is high-copper amalgams with high early strength (see Chapter 5, page 74). Restorations of these amalgams may be polished 8–10 minutes after the start of trituration, to avoid the need for the patient to attend for a second appointment.

Polishing is a procedure that makes amalgam restorations look their best, but it makes little difference to clinical performance. Polishing can be carried out in a number of different ways. The traditional method entails polishing with flours of pumice, mixed with water, followed by zinc oxide powder in an alcohol slurry, applied using a prophylaxis cup in a low-speed handpiece. This is a low-cost option for polishing, but it has the disadvantage of splatter from the rotating cup, which can be very messy and unpleasant for the patient. These procedures produce a mirror-like surface finish on an amalgam.

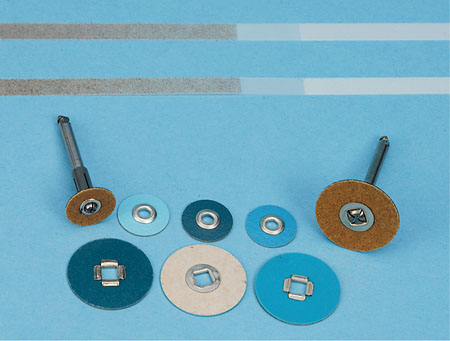

Amalgam restorations may also be polished using rubber cups impregnated with abrasive particles (Fig 7-1) or aluminium oxide discs (see Fig 7-2). These devices should be used with water coolant to avoid excessive heat generation in the restored tooth.

Fig 7-2 Examples of aluminium oxide abrasive discs and strips. Note the clear section in the centre of the strip, which contains no abrasive particles. This is the thinnest area, to aid movement of the strip through a tight dental contact point. The darker area to the left of the strip is more abrasive for shaping, and the lighter area to the right less abrasive for polishing. Smaller-diameter abrasive discs are useful in areas of limited access, such as around cervical cavities and palatally. Larger-diameter discs are useful for larger, flatter areas, such as when polishing extensive restorations involving the labial and incisal edge surfaces of anterior teeth.

Old, corroded amalgams with ditched margins that are restoring teeth free from caries may often be refurbished by recontouring with steel burs and polishing. This may restore a satisfactory surface finish and marginal adaptation, extending the life expectancy of the restoration. This is preferable to premature removal of the restoration, which invariably results in the unnecessary loss of additional tooth substance and increases the risk of irreversible pulpal complications. The refurbishment of an old corroded amalgam restoring the occlusal surface of a lower left second premolar tooth is illustrated in Figs 7-3 to 7-5.

Fig 7-3 An old, corroded amalgam restoring the occlusal surface of a lower left second premolar tooth. The surface is rough and the margins are ditched.

Fig 7-4 Reshaping the old amalgam with steel finishing burs. This procedure should be carried out with water coolant to avoid overheating of the amalgam, minimising the release of mercury vapour, and followed by polishing with abrasive points.

Fig 7-5 The finished, polished amalgam.

Composite Resins

Anterior composite resin restorations require optimum aesthetics. Effective methods of achieving a smooth, well-contoured surface and a high surface lustre are important. Many different abrasive systems are available to help achieve this aim. The most popular methods include polishing discs and strips impregnated with aluminium oxide particles, tungsten carbide finishing burs, finishing diamonds, rubber cups and points impregnated with abrasives and polishing pastes that can be used in association with discs, cups and points. Achieving a smooth transition from restoration to tooth without deficiencies or overhangs is of particular importance with composite resin restorations. This avoids unsightly staining of margins in clinical service. If the surface of the composite restoration is rough, it too will attract increased amounts of surface stains. The ability to achieve a smooth surface when polishing a composite resin depends on the:

-

finishing system used

-

shape of the surface being polished

-

size and percentage volume of filler particles within the composite resin

-

durability of bond between the filler particles and the matrix

-

degree of air inclusion within the bulk of the c/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses