7 Cosmetic Blepharoplasty

Orbital Anatomy

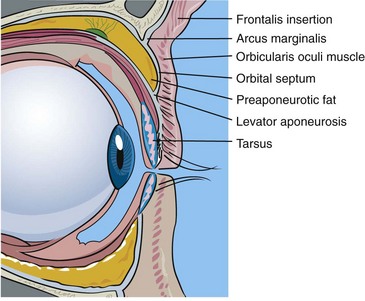

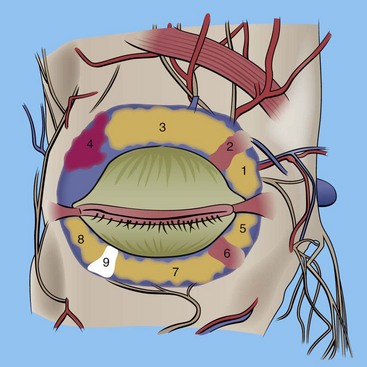

One must be particularly familiar with the structures of the upper eyelid (Figure 7-1):

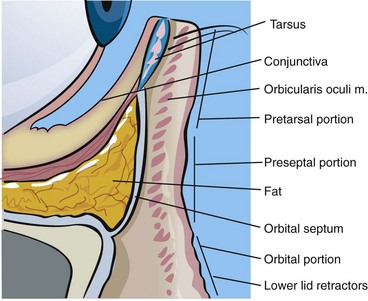

The key structures of the lower eyelid (Figure 7-2) are:

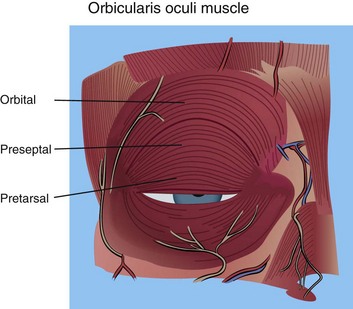

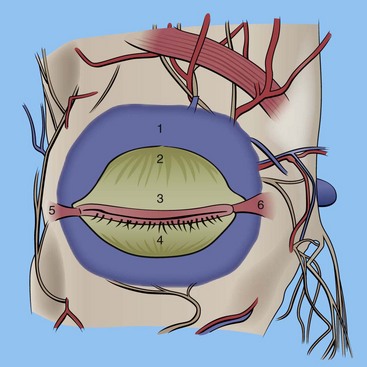

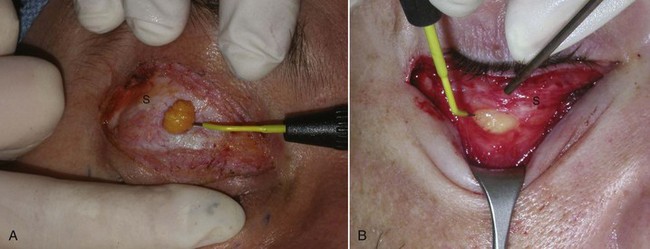

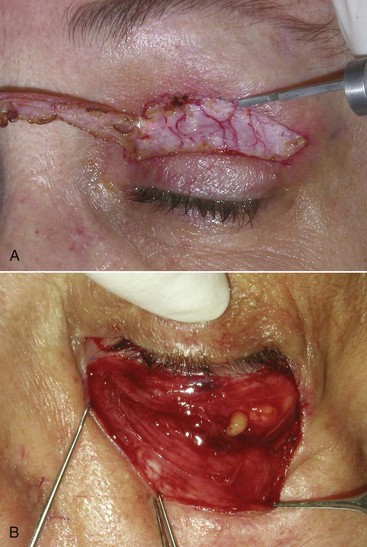

The eyelid skin is some of the thinnest in the body—sometimes as thin as 0.2 mm. The underlying concentric orbicularis oculi muscle is described in three portions: the pretarsal portion, which overlies the cartilaginous framework of the lids; the preseptal portion, which overlies the orbital septum; and the orbital portion, which overlies the bony orbit (Figure 7-3). Figure 7-4 shows the actual muscle intraoperatively. The orbital septum is a connective-tissue layer that is an extension of the periosteum and separates the muscle layer from the periorbital fat (Figure 7-5). Figures 7-6 and 7-7 show clinical views of the orbital septum.

FIGURE 7-4 A, Orbicularis oculi muscle in the upper eyelid. B, Concentric muscle fibers in the lower lid.

Müller’s muscle is an autonomic muscle that lies deep to the levator palpebrae superioris muscle (Figure 7-8) and is responsible for approximately 2 mm of upper eyelid opening.

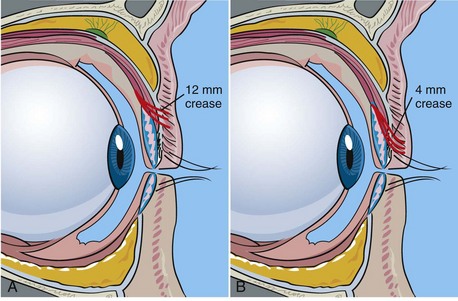

The upper eyelid crease is determined by the insertion of the fibers of the levator aponeurosis into the eyelid skin. The normal Caucasian upper eyelid crease is 10 to 12 mm above the lashes in females and about 8 to 10 mm above the lashes in males (Figure 7-9, A). The Asian eyelid crease is 4 to 6 mm above the lash line and is inferiorly positioned because the levator aponeurosis fibers attach at a lower level (see Figure 7-9, B).

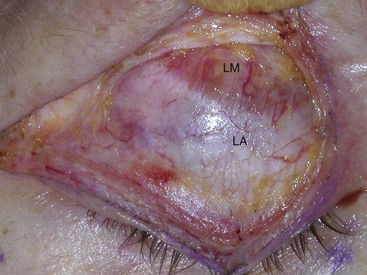

The globe is cushioned by periorbital fat positioned into distinct fat pads in the upper and lower eyelid. These fat pads are frequently reduced or repositioned in cosmetic blepharoplasty. There are two fat pads in the upper eyelid: the medial (sometimes called nasal) and the central (Figure 7-10). The superior oblique muscle separates the medial and central fat pads in the upper lid. Also sitting in the lateral upper orbit is the lacrimal gland. This gland is pinkish and similar in consistency to salivary glands; despite its appearance, it is sometimes mistaken for fat and removed, with disastrous consequences. It is imperative for the novice surgeon to remember that there are only two fat pads in the upper lid. The lower eyelid has three fat pads: the medial (sometimes called nasal), the central, and the lateral (sometimes called temporal). In the lower eyelid, the inferior oblique muscle separates the medial and central fat pads, and the arcuate expansion of the inferior oblique muscle separates the central and lateral fat pads (see Figure 7-10). Figure 7-11 shows the right upper lid lacrimal gland. Innervation of the periorbital area is complex; the main innervation of the eyelids and associated structures is given in Box 7-1.

Aging Conditions of the Eyelids and Periorbital Areas

As we age, various changes become evident in the eyelids (Figure 7-12). The most obvious is the presence of brow ptosis. Most young males have flat brows at or above the level of the upper orbital rim, and most young females have arched brows above the level of the upper orbital rim. As we age, the brows and forehead begin to droop, and this ptosis causes redundant tissue. This is especially obvious in the lateral orbital region of the upper eyelids, a condition known as hooding.

Some patients will present with a chief complaint of “fat bags,” but in reality they have hypertrophic orbicularis oculi muscles in the lower lids. Patients with orbicularis hypertrophy show increased lower lid bulges when asked to smile and squint. Figure 7-13 shows a patient with lower eyelid orbicularis oculi hypertrophy.

Xanthelasma is an accumulation of yellowish plaques in the upper eyelid skin (Figure 7-14). This condition is related to increased blood levels of cholesterol or hyperlipidemia and sometimes with diabetes. These lesions are treated by surgical excision or laser ablation and frequently recur.

Periorbital festoons are swellings from skin damage and fat in the infraorbital or midface area (Figure 7-15). These are challenging areas to correct. They are frequently treated with skin resurfacing or direct excision.

Diagnosis and Patient Selection

Adequate time must be scheduled for eyelid evaluation—on average 30 to 45 minutes. During that time, health history, procedures, complications, pre- and postoperative considerations, fees, and anesthesia evaluation must be discussed (Box 7-2). Pictures are everything in cosmetic surgery, and representative before-and-after images should be shown to give the patient an idea of what to expect. Having a list of patients who will serve as references to discuss their surgical experience with your prospective patients is a very useful adjunct. Additional information such as brochures, websites, before-and-after images, slide shows, and the like are very useful in supplementing patient information.

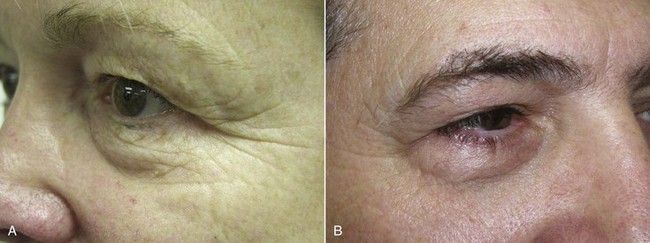

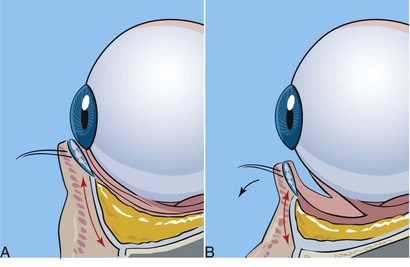

Several simple exams can be performed to evaluate the function of integral functions of related anatomy. The snap test involves pulling the lower eyelid inferiorly away from the globe and letting it go. The lid should snap back into position within 1 second (Figure 7-16). Failure to snap back into position or an elapsed time over a second to return to position indicates a lax lower eyelid and merits caution (Figure 7-17).

FIGURE 7-17 A snap test on a patient with very lax lids. Note the lid does not return to normal position.

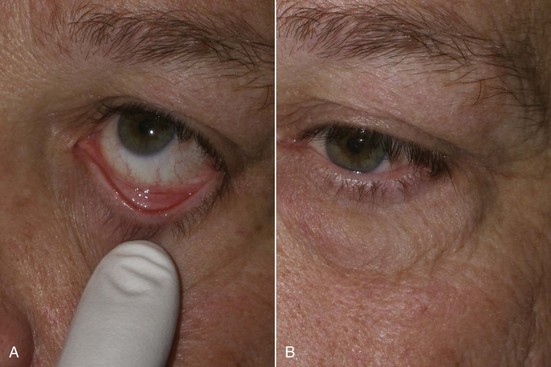

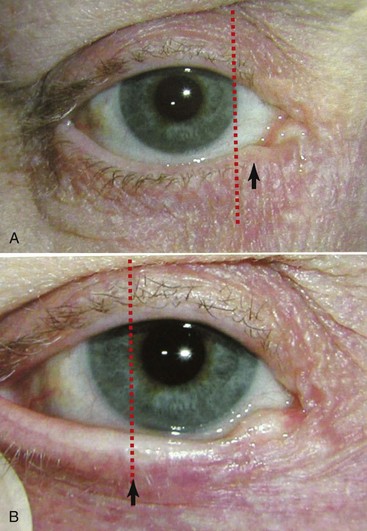

An additional test to evaluate eyelid laxity involves stretching the lower eyelid laterally and assessing the distance of travel of the punctum. When the normal lower eyelid is stretched laterally, the punctum does not move beyond the medial limbus (Figure 7-18, A). In the lax lower eyelid, the same maneuver will cause the punctum to move lateral to the medial limbus (see Figure 7-18, B).

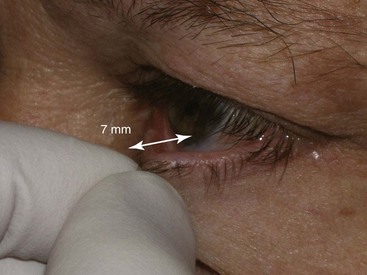

The pull test also assesses lower eyelid laxity and is performed by pulling the lower eyelid anteriorly from the globe and measuring the distance (Figure 7-19). A gap of over 7 mm indicates lower lid laxity and again merits caution and conservative blepharoplasty if not an adjunctive tightening procedure such as canthopexy.

A mechanism exists to protect the cornea during sleep or unconsciousness. This phenomenon causes the globe to rotate superiorly and cover the cornea behind the upper eyelid to prevent desiccation and is known as Bell’s phenomenon. It can be witnessed in some patients who sleep with their eyes partially open, showing the white sclera. A patient with dry eyes or without a protective Bell’s phenomenon could have catastrophic corneal damage from corneal exposure and drying if a lagophthalmos (inability to close the lids) should occur post blepharoplasty. To check for the presence of Bell’s phenomenon, the patient is asked to close the eyes, and the examiner gently pries the lid open with their fingers; the eyeball should roll back and protect the cornea, and the examiner should see only the white sclera (Figure 7-20, A). A patient with an abnormal Bell’s phenomenon has their corneal surface exposed and visible with eyes closed and pried open (see Figure 7-20, B).

As we addressed in depth in Chapter 3, photographic images should be standardized or they are useless. Common background, position, lighting, and pose are requirements.

A minimum preoperative series should include:

Figure 7-21 shows a typical preoperative series used by the author.

Treatment Planning

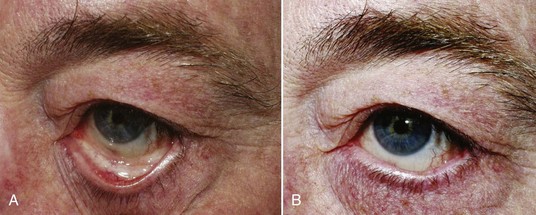

Although some patients will present for isolated upper or lower eyelid procedures, many patients will request four-quadrant blepharoplasty with browlift and possibly other cosmetic facial procedures. Upper eyelid blepharoplasty is pretty standard in technique, but lower lid approaches vary in internal and external approaches to the fat. For years, external skin-muscle approaches were used with a subciliary incision. This involves violating the middle lamella (orbital septum) and excising skin and/or muscle from the external surface. This approach is still utilized, but most contemporary oculoplastic surgeons maintain that violating the middle lamella can be a prime cause of lower lid malposition, which can result in lid retraction with scleral show, ectropion, and dry eyes (Figure 7-22). Transconjunctival approaches have become more popular because the orbital septum is spared, there is no external incision, and lower lid malposition is rare. The conventional transconjunctival approach is a retroseptal surgical approach and spares violation of the orbital septum. When dealing with transconjunctival approaches, alternate methods are used to address excess skin. In young patients, no ancillary skin removal may be required. In older patients, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser resurfacing of the eyelid skin is my treatment of choice. My second most common choice is 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and skin-pinch techniques are my third choice and can address the skin excess without invading the lower septum. These techniques will be discussed in detail later in the chapter.

Preoperative Marking

Upper Eyelid

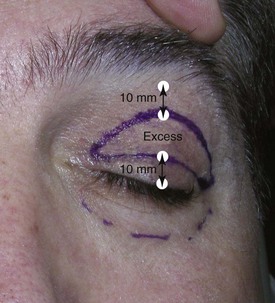

The first step is to decide where to locate the upper lid crease. Most males (non-Asian) have an upper lid crease of about 8 mm above the lashes, and most females (non-Asian) have upper lid creases of 10 to 12 mm above the lashes. Generally the lid crease is marked using the patient’s existing lid crease. Females desire a high lid crease to have a significant lid shelf on which to apply eye shadow. A high crease in males can feminize the result; 8 mm is an average position in the Caucasian male. The position of the upper lid crease can be discussed preoperatively, but I prefer 10 to 12 mm for females and 8 mm for males. I elevate the brow to a normal position (at the orbital rim for males, above the orbital rim for females) and have the patient open and close their eyelid to visualize the crease. The crease is then marked from the lateral canthus to the lacrimal punctum (Figure 7-23). Generally the center of the crease is at the 8 to 10 mm mark, and the ends of the crease taper to 4 to 5 mm high, creating an arc. But in many patients, their natural crease is almost a straight line, so attempting to make too high an arch can cause an artificial look.

The next step is to mark the upper extent of the blepharoplasty incision. The upper portion of the upper eyelid marking is made approximately 10 mm inferior to the junction of the forehead and eyelid skin. If one closely examines the skin inferior to the eyebrow, an area (generally corresponding to the bony orbit) where the smooth, thicker forehead skin meets the thinner crinkly upper eyelid skin can be seen. This is usually just below the finest hairs of the eyebrow but can be lower in some patients. A mark is made 10 mm below this junction; this defines the upper extent of the skin excision (Figure 7-24). If the surgeon leaves 10 mm from the lash to the lid crease and leaves 10 mm from the forehead/eyelid skin junction, this will give a total of 20 mm of upper eyelid skin preserved and enable lid closure. Always leave at least 20 mm of upper eyelid skin intact for normal lid function (Figure 7-25). This is, in the author’s opinion, the most critical point of successful upper eyelid blepharoplasty. Failure to observe can result in overexcision of upper eyelid skin with permanent lagophthalmos.

FIGURE 7-24 Upper extent of the eyelid incision is marked 10 mm inferior to the junction of forehead and eyelid skin.

The final step is to connect the incision at the lateral canthal area. If a brow lift is not planned, then a “Bird beak” incision is used with a lateral extension of extra lid skin excised to correct hooding (see Figure 7-26, A). If simultaneous brow lift is planned, lateral hooding of the upper lid is corrected, and a “Napoleon’s hat” incision is used for the lid skin (Figure 7-26, B). Since the brow lift elevates the lateral lid skin, excision of lateral lid skin is unnecessary. (These nicknames are used by the author for teaching purposes and are not official nomenclature in the ophthalmologic literature.) It can be of value to extend the lateral excision into a natural crow’s-foot wrinkle; this may better blend the scar. Although some authors recommend extending the lateral incision up to 15 mm lateral to the orbit, this can leave a scar that looks unnatural and takes much longer to heal. I personally do not extend the lateral portion of the incision past the bony lateral orbital in most patients. When I do, it is generally not more than 5 mm or so. Another important pearl is that this lateral incision extension should always taper up (like a smile) and never inferiorly (like a frown). The latter can look unnatural.

When addressing the medial junction of the upper and lower marks, it is important to avoid the multicontoured depression lateral to the nose. Generally, the medial corner of this incision ends at the punctum. If the excision is carried out laterally onto the nose, an obvious scar will be apparent, and scar webbing of this multicontoured area can occur (Figure 7-27).

After the lid markings are made, a “pinch test” is made to check that the lids can still be closed with the prospective skin excised. With the brow elevated to a normal position, the skin is pinched with a forceps; the lashes should just evert, but the eyes should still be able to remain closed (Figure 7-28). This test reinforces that excessive skin is not removed and is especially critical when simultaneous brow lift is planned. If simultaneous brow lift is planned, much less skin should be removed relative to the amount of anticipated lift.

An additional means of marking the upper eyelid is to mark the upper lid fold. This not only provides an alternative means of determining the superior extent of the upper lid incision but can serve to verify other marking methods for accuracy. This is done by having the patient stand in front of the surgeon and stare at a fixed point. I generally place my index finger on the tip of my nose and ask the patient to focus on that point. The patient must be able to stare straight ahead at my fingertip without looking up or down, so I adjust my position to accommodate patient height. The point is to have the patient look straight ahead with a focused gaze, brows relaxed. I then use the surgical marker to make dots on the bottom of the overhanging skin fold of the upper lid (Figure 7-29). These dots are amazingly accurate in relation to what will become the superior extent of the upper blepharoplasty incision and will usually correspond to the line marked in Figure 7-24.

I generally use both of these methods to mark my superior extent of the upper blepharoplasty incision. First I use the “stare at my finger” technique and make a series of dots across the bottom of the upper lid fold, as shown in Figure 7-29. Then with the patient seated and the brow elevated, I reconfirm these marks by measuring 10 mm below the junction of the forehead/eyelid skin, as shown in Figure 7-24. These dots and lines usually correspond very closely and serve as affirmation of the proper excision of the superior margin.

A third means of determining the upper extent of the incision is usually reserved for the experienced blepharoplasty surgeon. With the patient lying down (or the brow manually elevated to its normal position), the center of the upper lid is pinched with a forceps until the upper lashes just begin to evert (Figure 7-30). A mark is made at the pinch point. This is repeated on the lateral and medial portions of the upper lid, and these marks are then connected. This ensures adequate skin preservation to close the lids. Again, this technique is best reserved for the experienced blepharoplasty surgeon.

Lower Eyelid Markings

If an external skin-muscle incision is planned for the lower lid, a line is marked 2 mm below the ciliary margin. This mark is then extended just to the orbital rim in a horizontal direction (Figure 7-31). This lateral incision can be incorporated in a natural crow’s-foot wrinkle, but if extended too far beyond the orbital rim, an unsightly scar may result that takes months to resolve. It is important to leave at least 5 to 7 mm of intact skin between the upper and lower lateral incisions (see Figure 7-31).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses