7

Chronic Inflammatory Processes

There are seven-day wars and there are hundred-day wars, and having experienced both we can tell you that there is definitely a difference. The common factor is that there is conflict even though the “style” changes. When does the acute short-term blitz become a long drawn-out conflict? That’s s what this chapter is all about. A lot of shells have gone over the trench since we began exploring the defensive system of inflammation, so we would like to do a quick review of some of the essential aspects. Please turn to the Introduction (page ix) and review the basic types of inflammatory reactions. Once you have done that, come right back here (we are waiting, and the clock is ticking… ).

Why did we insert this chapter after the chapters on the immune system and hypersensitivity? Because chronic inflammation involves the immune system and immunologic responses. The cell that orchestrates most chronic inflammatory reactions is the CD4+ T cell. Without knowledge of the immune system, chronic inflammation would be unfathomable.

It is important to point out that there is no clear dividing line between acute and chronic inflammation. If the cause of the initial injury is not completely eliminated, acute inflammation will gradually give way to chronic inflammation, but there is no set time sequence.

How do you know a chronic situation when you see it?

Whereas acute inflammation involves exudative reactions, in which fluid, plasma proteins, and cells leave the bloodstream and enter the tissues, chronic inflammation is characterized by infiltration of injured tissue by leukocytes, as well as by proliferative responses, where cells are stimulated to multiply.

Interestingly, a majority of the most crippling diseases of humans involves chronic rather than acute inflammatory reactions. Leprosy, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, chronic pyelonephritis, syphilis, liver cirrhosis, and periodontal disease are all examples of chronic inflammatory diseases.

When we said there is a difference in “style” we meant that tissue damage frequently begins “quietly” as a low-grade, smoldering response that becomes apparent only after much damage has been inflicted on the tissue.

General considerations

Chronic inflammation may develop in two ways, depending on the nature of the inflammatory stimulus or stimuli involved:

- It may supersede an acute inflammatory response that is not completely resolved. This occurs when the inflammatory response is unable to eliminate the injurious agent.

- It may develop in the absence of an antecedent acute response. This is the case when the immune system responds to a foreign antigen. Or, this may occur when the infectious agent is of low toxicity as compared with agents that are capable of initiating an acute inflammatory response.

The term chronic denotes an inflammatory response that persists for more than a few days or weeks. A chronic inflammatory response is characterized by a proliferation of:

- Fibroblasts,

- Vascular elements,

and an infiltration of “round cells” (also referred to as “mononuclear cells”). These are:

- Lymphocytes

- Macrophages

- Plasma cells (sometimes)

Collectively, these elements comprise chronic inflammatory tissue. In chronic inflammation, macrophages and lymphocytes may at times be the first cells to respond. (In an acute response you would expect neutrophils first.) In fact, the T-helper cell and the macrophage are the key cells in initiating a chronic inflammatory response.

Chronic inflammation is basically an immune response initiated in response to persistent antigen.

In chronic inflammation, the number of neutrophils is reduced relative to the number of mononuclear cells. (Why do neutrophils predominate in acute inflammation? What attracts them to a site of injury? We know you are growing weary, but if you can’t t handle these questions you had better review chapter 2—we won’t t tell anyone!)

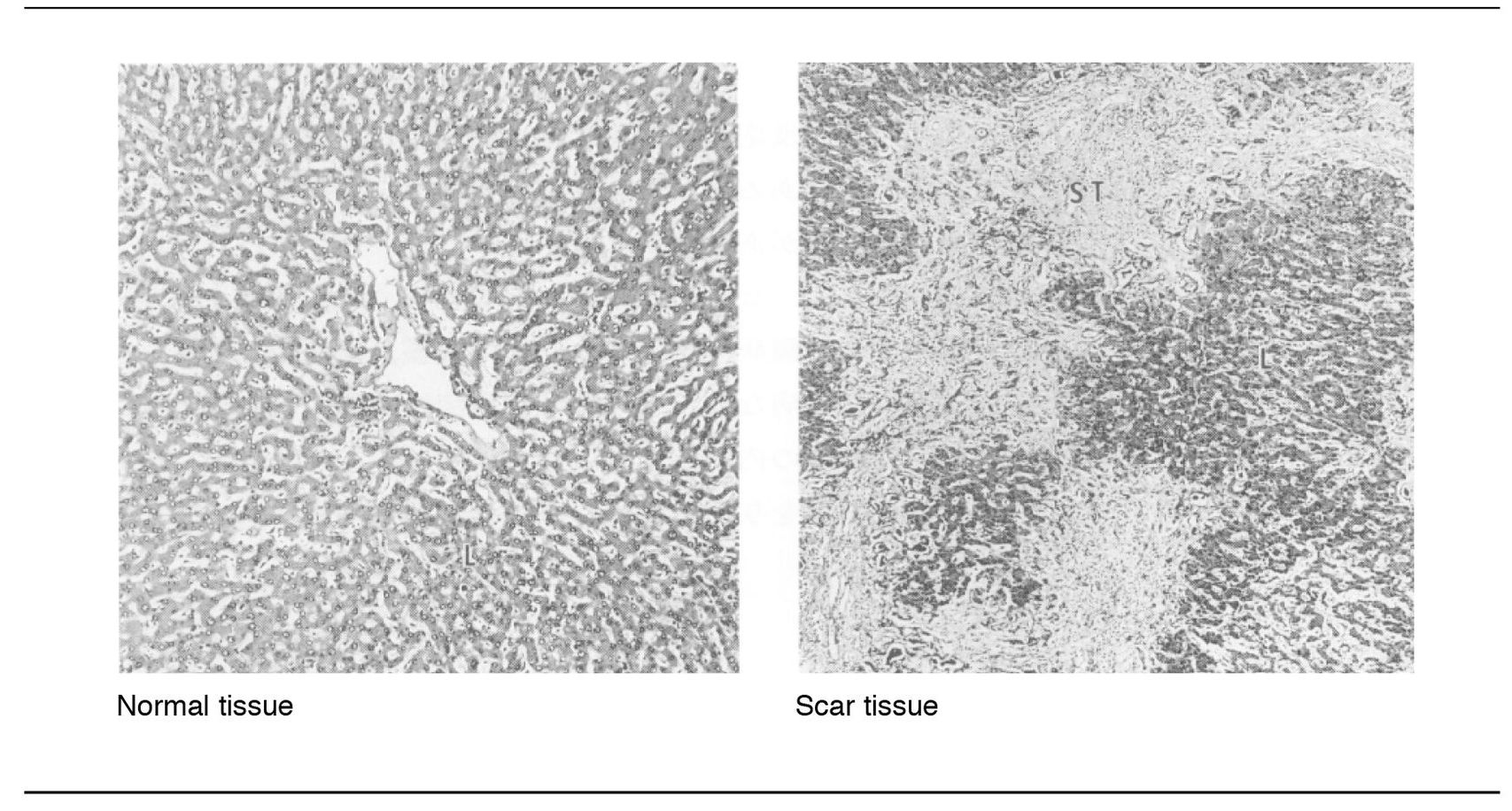

Chronic inflammation is often associated with irreversible destruction of normal parenchyma. Fibrous connective tissue then fills the resultant defects. A good example of this is liver cirrhosis, where hepatic lobules are replaced by collagen fibers (Fig 7-1).

Fig 7-1 Replacement of liver tissue by fibrous connective tissue.

What occurs is a seesaw process of destructive mechanisms (inflammatory-degenerative) and healing (scar tissue), the end result of which may be permanent loss of function in the affected parts of the body.

Clinically, pain is often minimal or absent. Chronic inflammation may go unnoticed by the patient until it is too late to save the affected organ or organs. Thus, it lacks the warning signals that are so prominent in acute inflammation—swelling, heat, redness, and pain.

There, now you have all the general considerations. Proceed only if you hunger for juicy details. But, before we launch into details, you should remember that there is no clear boundary between acute and chronic inflammation (except in our chapters, of course). You can see that this may be so because such things as infectious agents, foreign bodies, chemicals, and immunologic factors may each produce inflammatory reactions, acute and chronic. Consequently, one could expect to see a great deal of overlap between acute and chronic responses.

Causes of chroni inflammation

The basic cause of chronic inflammation is the persistence of etiologic factors that are difficult for the body to eliminate. Several major groups of causative agents are recognized.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses