Treatment planning

Overall health and oral care of patients and the role of endodontics within it

Conversely, the knowledge and skills of endodontics must be deployed judiciously to ensure that the patient receives appropriate care, meaning that the specialist must also understand the broader context within which their expertise is exercised. In simple terms, this means that the dentist should be well versed in all aspects of dentistry, understanding the role of each aspect in overall patient management, as well as being aware of potential overlaps and interactions between the subdisciplines. In the context of a healthcare profession, the “endodontist” must, therefore be a human being first, dentist second and endodontist last (Fig. 5.1).

Treatment option selection and treatment planning

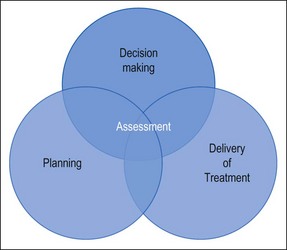

Treatment planning, as the term implies, is the planning of the management of a patient’s dental and oral problems in a systematic and ordered way that assumes a complete knowledge of the patient’s needs, the precise nature of the problems and the prognoses of possible management options under consideration. In the case of simple dental problems, the dentist may be able to identify the problem efficiently, characterize it together with the patient’s needs and select the correct management option expeditiously. In the case of complex dental problems, it may be rare for both patient and dentist to develop such complete pictures of the problems and outcomes of restorative options as early as the first consultation. The dentist must gauge the problems correctly, as well as the patient’s attitude, motivation and compliance. The phase of assessment (establishment of a more complete picture of the problem(s) and patient compliance), therefore, often overlaps with the phases of decision making, planning and delivery of treatment (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2 Interrelationship between assessment and decision making, planning and delivery of treatment

Even under the best set of circumstances, the most complete and definitive picture of the problems may not be reached because of deficiencies in diagnostic certainty and prognostic data on treatment outcomes. Despite this, dedicated, active practice, with continuous proactive personal development may propel a dentist to the state of mastery of their field relative to contemporary knowledge. Variations inherent in dentists’ philosophy, knowledge, experience, skills and judgement can give rise to differences in treatment planning between clinicians. Conscientious dentists, therefore, strive for improvement throughout their professional lives in what has now become formally recognized as continuing professional development (CPD). Active engagement in CPD is mandatory in some countries but not all. Unfortunately, some dental practitioners take the receipt of their practising licence as the end of formal professional development. Their frame of reference extends no further than the teachings at undergraduate level. Decision-making for them is a matter of following the simple heuristic decision-tree delivered as expedient undergraduate teaching. Their knowledge is therefore written in black and white, is clear and simple and may still serve the needs of those patients falling into the “central tendency” of disease presentation. It may not, however, serve those presenting with problems lying on the fringes of the normal distribution of the particular disease. The intellect and skills of such practitioners may consequently be stunted from flowering into their full potential.

The ideal treatment-planning scenario

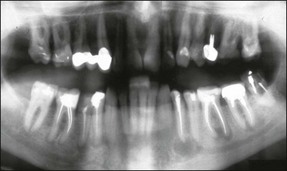

The textbook depiction of treatment planning commences at the first encounter with the patient, when a full assessment is made of the patient’s overall dental and oral problems. In this diagnostic phase, a detailed systematic appraisal is made in the classical manner described in Chapter 4. The end point of this is a series of conclusions about the general health of the patient and their current oral and dental problems; these will be juxtaposed with the patient’s own perception of their problem(s) and desires for correction of the same. The dentist’s insight will include the state of the patient’s dentition, periodontium, the teeth (presence of caries or tooth surface loss and their pulpal and periapical status), any restorations and soft tissues. A number of different solutions will be possible for management of each of the patient’s problems but the specific treatment options selected will be dictated by the particular effects of interaction of these problems on the patient’s desires, which may include their well-being, aesthetic demands, and functional requirements (eating, speaking, socializing). Factors such as technical feasibility, cost and time involved, dentist’s preferences based on their skills and knowledge, and the patient’s age, means, wishes and compliance in oral care may all play a part in determining the final outcome. In the ideal scenario, each option should be evaluated in an objective way taking the above factors into account, weighing the effectiveness and projected long-term prognosis (based on outcome data) with compliance, cost and time commitment. As the number of dental problems to be addressed increases (Fig. 5.3), so does the interaction between options for individual problems. This may have the overall effect of either complicating management or simplifying it because more radical solutions (such as extraction) become more appropriate. In any case, the options will be discussed with the patient and, after appropriate dialogue, negotiation and clarification, a mutually agreed choice of treatment or “treatment plan” will emerge (Box 5.1).

A plan is then made of the sequence in which treatment will be executed, called the “plan of treatment” (Box 5.2). This may be defined as a strategic list or maybe detailed by visit. Once the treatment is completed, the patient will be recruited to a recall system to evaluate and maintain the work. At these recall reviews, note will be taken of any changes and dealt with according to a preplanned scheme for dealing with failure. Planning for failure should be considered as part of the overall long-term treatment plan.

The reality of practice, informed consent and medical records

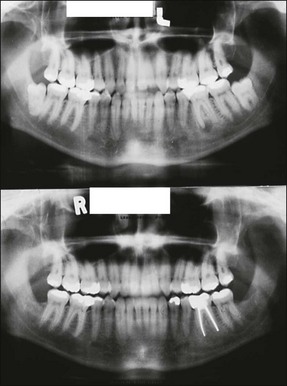

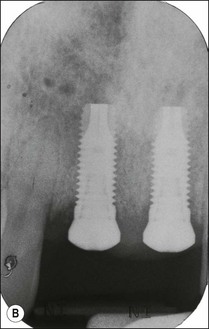

In general dental practice, where a patient has often been under long-term care by a particular practice or dentist, the majority of interactions with the patient are part of continuing care. A plan of management will have been established at the first encounter at some point in the past and, in the simplest cases, requires no more than a review (recall) to evaluate a change in overall status and provide motivation for maintenance. Under these circumstances, the sudden precipitation of a pulpal or periapical problem may be managed in isolation as long as there are no complex restorative implications (Fig. 5.4). Where there are such complex restorative implications, the lack of insight or desire (on the part of the dentist) to tackle them may influence outcome of the endodontic problem (Fig. 5.5). It is therefore important that a rational analysis of the situation is performed conscientiously and difficult restorative decisions taken promptly as necessary, rather than procrastinating to another time when the situation is likely to be worse. Recognition of personal limitations in knowledge and skills, or seeking appropriate referral, is the key to finding a solution.

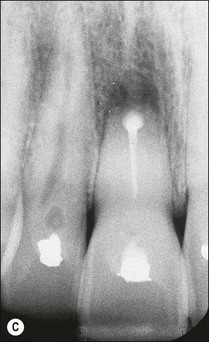

It is not uncommon and perfectly valid for patients on long-term recall, to have the supervising dentist place individual teeth on probation to review their status at a subsequent time because of uncertainty about a diagnosis or the progression of a lesion (Fig. 5.6a). A number of potential problems, not causing current difficulties will, therefore have been identified but a mutually agreed decision made between patient and dentist to leave the tooth/teeth alone and periodically review them. Such a plan of action is not uncommon both in unrestored mouths and in those that are heavily restored and on the borderland of catastrophic transition to a different, perhaps partially edentulous state. The latter situation describes the not uncommon condition of an ageing or restoratively ravaged dentition, where one further change could precipitate a radical review of the overall dental strategy for the patient, with major implications of time and cost. Small changes to the situation may be managed by minimal intervention and a “patchwork” approach but this also demands a more vigilant rather than complacent review strategy. The situation, however, must be clearly recognized and understood by both the patient and dentist using the so-called informed consent approach. The tooth in Figure 5.6a has been retreated (Fig. 5.6b) and placed on continuing review until a mutually agreed decision can be reached with regards to which of the previously discussed restorative options to pursue.

Factors influencing treatment planning

Illustration of factors affecting treatment decision making using maxillary incisors as an example

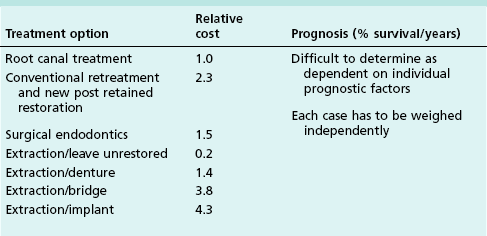

A cost–benefit analysis should be performed to aid the decision-making process as illustrated in Table 5.1. The outcome of such an analysis, though, is likely to be different depending upon the exact details of the situation. A recent health economic study using a Markov model evaluating the cost-effectiveness of clinical intervention over the life-time of an adult patient revealed that root-canal treatment is highly cost-effective as a first line intervention for a maxillary central incisor. Orthograde retreatment is also cost-effective, if a root-canal treatment subsequently fails, but surgical retreatment is not. Implants may have a role as a third line intervention if root canal retreatment fails.

Scenario 1

Consider the not uncommon scenario of the pulp in a maxillary incisor of an otherwise intact dentition becoming compromised by a severe traumatic injury in a young, mature adult (Fig. 5.7a). The options of vital pulp therapy or root-canal treatment may be considered. The choice will centre on the prognosis of each treatment (based on biological factors) and the long-term benefit to the patient. If the tooth is not restoratively compromised and the root is mature, the high prevalence of pulp necrosis in such cases may lean the decision towards root-canal treatment and the appropriate restoration as having a high chance of success (Fig. 5.7b,c). Other restorative factors may not come into the equation at this stage but will be discussed with the patient.

Scenario 2

If, under the same circumstances, the patient was younger with an incompletely formed root, the decision may now lean towards the more conservative vital pulp therapy (Fig. 5.8a) in order to aid completion of root formation and improve the long-term restorative prognosis (Fig. 5.8b). In the event that the traumatic injury in such circumstances is accompanied by severe coronal tooth fracture, the restorative prognosis may be further jeopardized (Fig. 5.9). Consideration of early replacement may have to be tempered by the psychological need to avoid loss of the tooth, as well as to delay permanent replacement during the growth phase of the individual, especially if an implant-retained crown is a possible alternative. The compromised tooth may, therefore, be retained as a suitable space maintainer until a more definitive solution can be executed.

Scenario 3

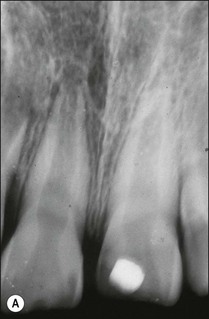

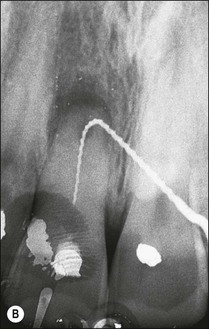

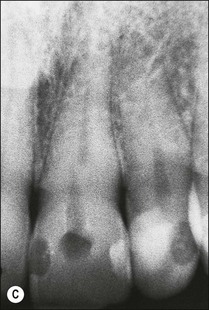

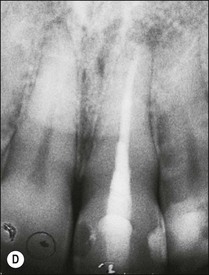

Consider an identical scenario but where a traumatized, intact, mature, maxillary central incisor has been left untreated for years as the pulp slowly succumbs and the patient seeks attention either because of an acute infection or the discoloration caused by secondary dentine formation and/or pulp necrosis (Fig. 5.10a). On radiographic examination, it is found that the canal is sclerosed (Fig. 5.10b) and only evident in the apical third of the root associated with a periapical lesion. Now other considerations come into play, including the potential for successful outcome by conventional or surgical means, as well as the desire for correcting the discoloration. In the matter of the former problem, it has to be established whether the operator is confident of locating the canal using a conventional coronal approach (Fig. 5.10c), which would improve the chances of success (Fig. 5.10d). If not, injudicious dentine removal may result in compromised restorability of the tooth. A surgical approach may stand a better chance of finding the canal but may not help eradicate the major part of the infection in the root-canal system, compromising the chances of successful healing (Fig. 5.11). In addition, the absence of access to the pulp chamber also compromises the chances of internal bleaching of the tooth to help correct the discoloration. In this scenario, there is an increasing number of uncertainties as outcomes are less predictable. The decision-making now has to be aided by weighing the relative chances of success of the different endodontic options and, finally, also the restorative/aesthetic outcome.

Fig. 5.10 (a) Discoloration of tooth following trauma; (b) radiographic evidence of pulp calcification and dentine sclerosis; (c) example of sclerosed canal in maxillary incisor; (d) canal successfully negotiated and obturated

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses