Chapter 6

Non-plaque-induced Periodontal Diseases I: Gingival Lesions

Aim

This chapter aims to provide an overview of less common conditions that may present as gingival lesions and which do not have plaque as the primary aetiological agent. Some are gingival manifestations of systemic diseases and some are lesions that are confined to the gingival tissues.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the practitioner should be able to identify more common non-plaque-induced gingival conditions in young patients, feel empowered to reassure parents and young adults and to manage some of these conditions in their practice. They will also be able to identify key conditions that require specialist referral for further investigation and joint medical/surgical management.

Introduction

The 1999 International Workshop for Classification of Periodontal Diseases used the term “non-plaque-induced” to describe conditions where plaque control measures alone cannot be used to treat a condition (see Chapple and Gilbert 2002 for a critique of the classification). Some of these lesions are relatively common (e.g. childhood viruses), whilst others are extremely rare (see Table 1-1). Many of the conditions do not usually present in younger patients, e.g. those of specific bacterial origin. In contrast, some other non-plaque-induced gingival conditions that may present in the younger age groups were omitted, e.g. granulomatous disease. Therefore a more comprehensive list of the non-plaque-induced gingival conditions that may present in young patients is shown in Table 6-1. The salient features of the more common conditions are briefly discussed below.

| Type of lesion | Aetiology | Condition/lesion | GDP/refer |

| Infective | viral | herpangina | GDP – r |

| hand foot and mouth | GDP – r | ||

| herpes simplex I (primary) | GDP – r | ||

| herpes simplex I (secondary) | GDP – r | ||

| molluscum contagiosum | refer | ||

| fungal | candidosis | GDP – r | |

| linear gingival erythema (candidosis) | refer | ||

| deep mycoses | aspergillosis | refer | |

| blastomycosis | refer | ||

| coccidiomycosis | refer | ||

| cryptococcosis | refer | ||

| histoplasmosis | refer | ||

| geotricosis | refer | ||

| Genetic | fibromatosis | hereditary gingival fibromatosis | GDP – r |

| coeliac disease | oral/gingival ulceration | refer | |

| anatomical variations | delayed gingival retreat | GDP | |

| Systemic diseases that manifest within the gingiva | haematological disease | ||

| – benign conditions | agranulocytosis | refer | |

| cyclical neutropenia | GDP – r | ||

| familial benign neutropenia | GDP – r | ||

| myelodysplastic syndromes | refer | ||

| – malignant conditions | myeloid leukaemia | refer | |

| b-cell lymphoma | refer | ||

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | refer | ||

| granulomatous inflammations | Crohn’s disease | refer | |

| sarcoidosis | refer | ||

| Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome | refer | ||

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | refer | ||

| tuberculosis | refer | ||

| disseminated pyogenic granulomas | refer | ||

| immunological conditions | hypersensitivity reactions | GDP – r | |

| lichen planus | refer | ||

| C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency/dysfunction (angioedema) | refer | ||

| Traumatic | thermal | burns | GDP |

| chemical | ulceration | GDP | |

| physical | gingivitis artefacta | refer | |

| electrical | burns | refer | |

| Drug-induced | immune complex reactions | erythema multiforme | refer |

| lichenoid drug reactions | GDP – r | ||

| cytotoxic drugs | methotrexate | refer | |

| hydroxychloroquine | refer | ||

| pigmenting drugs | doxycycline | GDP | |

| drugs | oral contraceptives | GDP | |

| antimalarials | GDP | ||

| anti-retroviral drugs (anti-HIV drugs) | trigeminal nerve neuropathy | refer |

GDP, manage in practice.

GDP – r, manage in practice but refer if concerned or complications arise.

Viral Infections

Herpangina

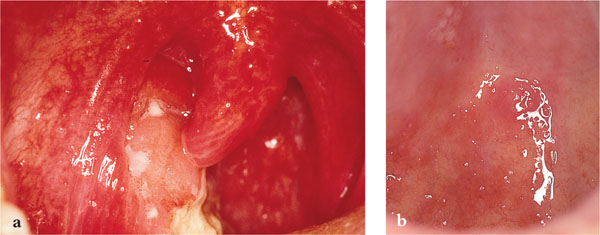

Herpangina is caused by Coxsackie viruses (usually A4 and A10), which are RNA viruses belonging to the picornavirus family. It usually presents within the first few years of life with a prodrome characteristic of viral infections. The baby or child will be irritable, febrile and will have a general malaise with loss of appetite. Cervical lymph nodes enlarge and vesicles, which typify viral infections, appear on the soft palate and fauces (Fig 6-1a,b). These can coalesce and ulcerate causing pain and problems swallowing, but the gingivae are often spared.

Fig 6-1 (a) Ulceration of the pillars of fauces, soft palate and tonsillar fossa following rupture and coalescence of several vesicles containing coxsackie virus. (b) Vesicles affecting the hard palate adjacent to the upper molar teeth are classic features of herpangina. Vesicles are also present on the soft palate.

It is essential to reassure worried parents that the condition will “burn out” after seven to 10 days. In the meantime, the infant should be adequately hydrated, 0.2% chlorhexidine gently swabbed over areas of ulceration to prevent secondary infection and the use of an analgesic/anti-pyretic elixir (e.g. sugar free paracetamol paediatric syrup) may relieve symptoms. Eating is facilitated by applying topical lidocaine over painful areas or by giving cool fluids to drink. It may be necessary for nocturnal sedation (promethazine hydrochloride for infants over 12 months). Review within seven days to ensure the lesions are resolving and if concerned about dehydration at any time, refer to a paediatric hospital for parenteral feeding.

Complications of herpangina include acute parotitis, which is rare but may be confused with mumps.

Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease

This is caused by Coxsackie virus A16 or occasionally A4, A5, A9 or A10. Transmission is usually faeco-oral. It is very similar to herpangina but skin vesicles appear on the lateral margins of the toes and fingers (Fig 6-2). Oral lesions again present as vesicles affecting the oral mucosa, particularly the soft palate, fauces and non-keratinised mucosa. Vesicles will ulcerate forming small yellow-centred ulcers with a red periphery.

Fig 6-2 Hand, foot and mouth disease often presents with fluid-filled vesicles affecting the palms of the hands.

The management is essentially the same as for herpangina, but all attempts should be made to keep the child’s hands out of their mouths – easier said than done! Complications are also largely the same as for herpangina with dehydration being the main difficulty to guard against.

Herpes Simplex Virus I (HSV-I)

This is a ubiquitous virus and the most common of the eight human herpes viruses. The primary infection may often be subclinical, but symptoms can present with varying severity. The virus remains dormant in the trigeminal ganglion (sacral ganglion in the case of HSV-II which causes genital herpes) and will cause secondary clinical infections when patients feel run down, are immunosuppressed, or following trauma or fever. Recurrent HSV-I affects about 20 – 40% of individuals who have had a primary infection. The most common recurring problem is damage to the lips from ultraviolet light resulting in a “cold sore” (herpes labialis).

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

HSV-I is the aetiological agent of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHG). PHG usually presents within the first three years of life, but the natural history is changing and reports of onset in teenagers and young adults, in particular, males are becoming more common (Fig 6-3). It is characterised by a prodrome, followed by small vesicles forming throughout the mouth on the oral mucosa, tongue and gingivae. The ulcers coalesce, develop a fibrinous coating and result in a painful stomatitis. The gingivae can appear fiery red in colour (Fig 6-4), but there are no skin lesions. There may be increased salivation because of pain on swallowing, submandibular lymphadenopathy and a raised temperature.

Fig 6-3 Irregular, shallow ulceration of the keratinised gingival margins is a classic sign of herpes simplex infection. The lesions have a ragged margin, yellow base and are very different from those of necrotising ulcerative gingivitis.

Fig 6-4 Fiery red gingivae with or without ulceration are characteristic of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Here, a fibrinous exudate is evident at the gingival margin of the deciduous upper right central incisor.

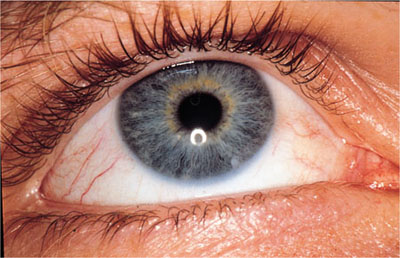

Management involves supportive therapy as for herpangina, ensuring against dehydration. Review is essential after seven days to ensure that the lesions are resolving and no complications are evident. Complications such as ocular and digit transmission (Figs 6-5 and 6-6) must be guarded against. Rarely, herpetic eczema may develop (Fig 6-7) or in extreme cases a herpetic meningoencephalitis.

Fig 6-5 A small area of ulceration around the medial can-thus of the eye due to HSV-1 transmitted from an oral infection.

Fig 6-6 A herpetic whitlow affecting the forefinger following cross-infection with HSV-1. Such lesions can have serious consequences if osteomyelitis develops as a secondary complication.

Fig 6-7 Herpetic eczema in a young boy following spread from an oral infection. Rarely, a herpetic meningoencephalitis may develop.

Secondary HSV-I Infection

Herpes labialis

Secondary HSV-I most commonly presents as herpes labialis and can be managed using topical aciclovir cream if diagnosed early. The ideal time to apply topical creams is when the first signs of a cold sore are evident (often a tingling sensation in the lips). Care should be taken treating patients with weeping cold sores, as these contain activ/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses