Chapter 6

Neuropathic Orofacial Pain

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to provide insight into those neuropathic conditions that may present to the dental practitioner.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the practitioner should:

-

be able to differentiate neuropathic pain conditions from other orofacial pain (OFP) disorders

-

understand the basic mechanisms of neuropathic pain

-

appreciate the diverse presentation of neuropathic OFP.

Case Presentation

-

Complaint. A 52-year-old married woman presented to a dentist for an initial consultation complaining of right-sided facial pain. She described an episodic pain occurring several times a day. The pain was shooting in quality and might last for a few seconds only in duration. When intense, the pain might be shooting for one or two minutes before subsiding. It tended to occur over several weeks before becoming quiescent for weeks or months. It was strictly right sided, closely related to the right maxillary molar teeth, radiating back into the right ear. It could be triggered by eating or smiling, but it could also be spontaneous. Following each bout of pain, there tended to be a pain-free window of several minutes before the next episode. The patient has complained of episodes of the pain for approximately 10 years.

-

Clinical history and examination. In the past, she had been referred to an endodontist, who carried out endodontic treatment of the maxillary right first molar. At that time, the endodontist expressed reservations as to whether this tooth was responsible for her pain. She felt, however, it was the “most likely tooth” to be the cause of the problem. After the root canal treatment, the pain subsided. A similar pain returned three months later. Intraoral soft tissue examination was normal.

-

Investigations. Bitewing and periapical radiographs failed to reveal any dental or periodontal pathology. The temporomandibular joints (TMJs) and masticatory jaw muscles displayed no tenderness.

-

Conclusion. The patient was referred to an OFP clinic and was diagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia. A brain scan was performed to exclude posterior fossa pathology. Gabapentin was prescribed and the pain subsided after titration to 1200 mg per day. The patient tolerated the medication well. Following a pain-free period of three months, the medication was slowly withdrawn and the patient remained pain free.

Introduction

The scourge of neuropathic pain is becoming increasingly recognised in the field of pain management. In the dental context, there is a tendency to focus immediately on trigeminal neuralgia. A greater appreciation of the basic pathophysiology increases the understanding that other orofacial conditions, including burning mouth syndrome and persistent idiopathic facial pain (atypical facial pain), are neuropathic in origin. What is surprising, however, is the rarity of neuropathic conditions presenting dentally, given that tooth extraction and root canal therapy may inflict significant trauma to the various dental nerves.

Neuropathic Pain

Pain can be categorised into nociceptive (transient), inflammatory and neuropathic. Nociceptive pain is experienced when, for example, sensitive teeth are exposed to cold drinks. It serves a protective function, therefore by removing the stimulus, the pain subsides. Inflammatory pain occurs following tissue injury and inflammation. An example of this is the pain experienced following the extraction of a tooth. This also serves a purpose in so far as we protect the tender tissue and thereby facilitate the healing process. Both nociceptive and inflammatory pain represent normal, adaptive functioning of the pain system.

Neuropathic pain, in contrast, does not serve a protective role. It arises from injury to nerves or to sensory transmitting systems. The pain system has been likened to an electronic burglar alarm (Fig 6-1). When primed, the alarm will activate on opening a window or on detection of an intruder. This can be compared to nociceptive and inflammatory pain – it does what it is designed to do. If, however, the wiring short-circuits, the system will malfunction. Short-circuiting of the nervous system gives rise to various neuropathic conditions.

Fig 6-1 A malfunctioning trigeminal nerve may be likened to a malfunctioning burglar alarm.

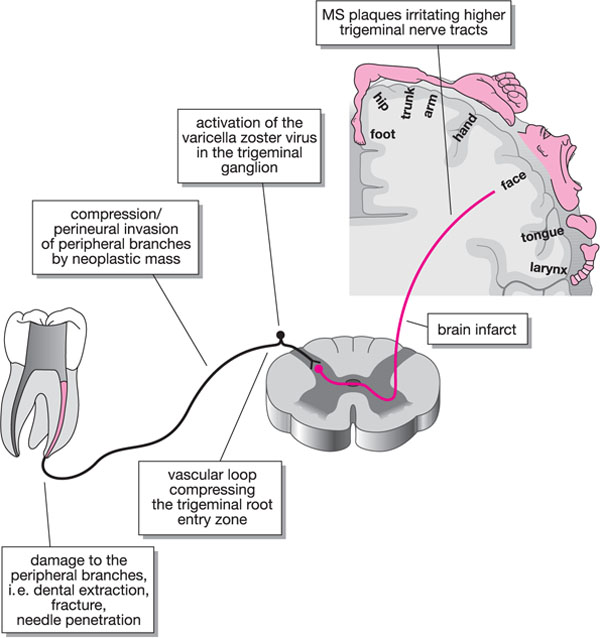

Neuropathic pain has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system”. Common examples encountered in dental practice include trigeminal neuralgia and the pain caused by injury to the inferior dental nerve following the extraction of a mandibular third molar tooth. Irritation, or short-circuiting, of the trigeminal nerve may occur throughout its course from its peripheral extremities in the facial region to more central portions in the brainstem and higher brain tracts. Although some neuropathic conditions improve with time, others pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas.

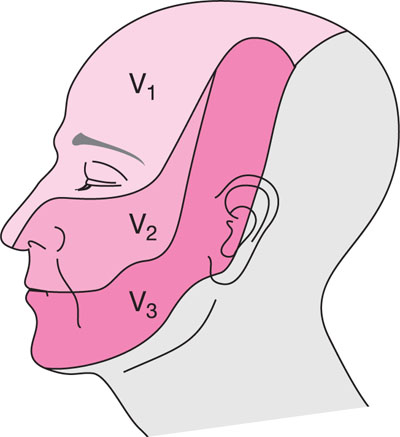

Anatomy

The trigeminal nerve conveys most pain impulses from the orofacial region. These impulses are transmitted via the three main branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary and mandibular nerves (Fig 6-2). In addition, several other cranial and cervical nerves are implicated in OFP transmission (Fig 6-3 and Table 6-1).

Fig 6-2 The trigeminal nerve is divided into the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3) branches.

Fig 6-3 “Short-circuiting” of the trigeminal nerve may occur anywhere along its course resulting in orofacial neuropathic pain.

| Nerve | Area affected |

| Trigeminal nerve | Oral cavity, nasal cavity, temporomandibular joint, anterior scalp, face and most of the external ear |

| Facial nerve | Tympanic membrane, external auditory canal |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve | Base of tongue, external ear, tympanic membrane |

| Vagus nerve | Posterior wall of external auditory canal and skin behind the ear |

| Cervical nerves (C2-3): greater auricular nerve | Angle of mandible, postauricular region and auricle |

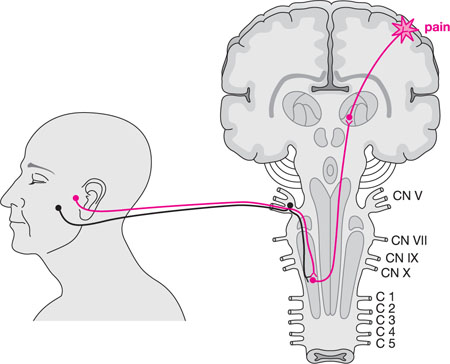

When a cranial nerve transmits noxious sensation from the orofacial region, the impulse travels to the trigeminal nucleus in the brainstem. In fact there is extensive convergence of orofacial sensory afferents from trigeminal, cervical and non-trigeminal nerves in the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Fig 6-4). This is thought to underpin the various referral patterns commonly seen in patients with OFP and thus contributes to diagnostic conundrums. A detailed knowledge of the cranial and spinal nerves implicated in OFP transmission is essential if undertaking the management of complex OFP.

Fig 6-4 The convergence of primary sensory afferents from the maxillary molar teeth and TMJ converging onto the same second-order neuron. This may give rise to pain referral from the TMJ to the maxillary molar region. (Adapted from JP Okeson, Bell’s Orofacial Pain, Chicago: Quintessence, 2005.)

Basic Neuropathic Mechanisms

Table 6-2 outlines the definitions used to describe neuropathic conditions. A common misconception in dentistry is the rarity of neuropathic phenomena that can present in clinical practice. Allodynia and hyperalgesia are everyday neuropathic occurrences. When a patient presents with a suspected dental abscess, the practitioner will typically percuss the teeth in the painful region. This may identify the offending tooth, as tenderness to percussion is a common manifestation of periapical pathology secondary to irreversible dental pulpitis. The production of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinins and histamine will often sensitise the pulpal and periapical pain fibres, lowering their firing thresholds. Subthreshold stimulation – gently tapping a tooth with a mirror handle – of sensitised nerves will produce pain – allodynia.

| Term | Description |

| Neuropathy | Pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system |

| Allodynia | Pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain |

| Hyperalgesia | An increased response to a stimulus that is normally painful |

| Hypoalgesia | A diminished response to a stimulus that is normally painful |

| Hyperpathia | An abnormal exaggerated reaction to a stimulus that is normally painful |

| Anaesthesia |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses