6

Hepatic Disease

I. Background

Description of Disease/Condition

Viral Hepatitis

Virally induced hepatitis can be caused by hepatitis A, B, C, D, or E strains and results in inflammation and destruction of the liver. It can present as acute or chronic persistent disease.

Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD)

Alcoholic cirrhosis is the terminal stage of ALD, where fibrosis and scarring has resulted in severe liver dysfunction. It is one of the main causes of death among alcohol abusers. Excessive alcohol intake can lead to fatty liver, hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Alcoholic hepatitis has a sudden onset typically following decades of heavy alcohol use (mean intake of 100 g per day) and is characterized by acute or chronic inflammation and parenchymal necrosis of the liver.1

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Malignant neoplasms of the liver that arise from parenchymal cells are called hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatocellular carcinomas are associated with cirrhosis in 80% of cases.

Pathogenesis/Etiology

Viral Hepatitis

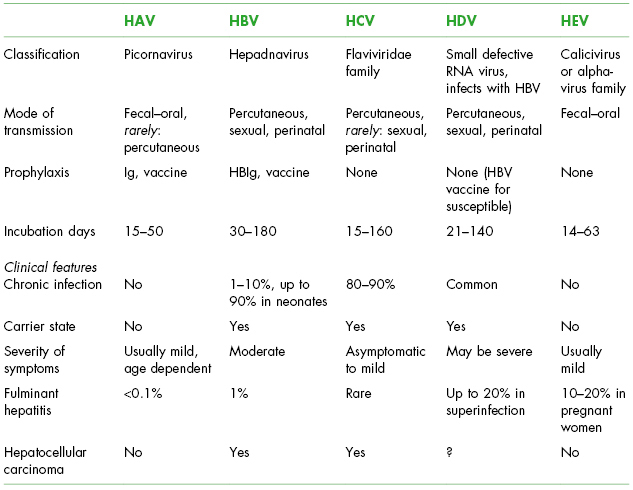

The five currently classified hepatitis viruses vary in transmission mode from primarily percutaneous (hepatitis B virus [HBV], hepatitis C virus [HCV], hepatitis D virus [HDV]) to primarily fecal–oral (hepatitis A virus [HAV], hepatitis E virus [HEV]). Characteristics are shown in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1. Characteristics of Hepatitis Viruses: Pathogenesis/Etiology/Disease Course

Adapted from Harrison’s Manual of Medicine; Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al. eds. 2009; New York, NY: The McGraw Hill Companies; 1264 pgs. Table 161-1.

HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; Ig, immune globulin.

HAV and HEV generally have clinical and morphological features of acute icteric hepatitis. Onset is usually insidious, with an initial prodromal phase lasting a few days and a variable combination of flu-like symptoms: fever, mild chills, abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. HAV viral particles are replicated only in hepatocytes and gastrointestinal epithelial cells and are released into the blood and bile. The damage of the liver cells results from a cell-mediated immune response.2 Peak infectivity correlates with the greatest viral excretion in the stool during the 2 weeks before the onset of jaundice or elevation of the liver enzymes.3

HBV and HCV infections are usually diagnosed several years and decades after acquisition on routine blood testing or after blood donation. Approximately 25% of patients with HCV infection will have hepatic fibrosis that can end in cirrhosis,4 on average 20 years after infection,5 while the other 75% have different degrees of hepatic inflammation. Factors that contribute to the development of cirrhosis are unclear; it may be genetic factors or the consumption of alcohol. If cirrhosis develops, the annual incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma is 1–4%.6

Clinical expression of HDV, that can infect only individuals who have HBV, is wide, and although it sometimes follows a benign course, the disease is clinically important. Studies have shown that most patients with HBV coinfected with HDV or HCV have more severe liver disease and more rapid progression to cirrhosis.7

ALD

Rather than being caused singularly by ethanol toxicity in hepatocytes, ALD is currently considered to be a multifactorial disease, where gender, genetic, and nutritional factors influence the disease progression to cirrhosis. The key process in the pathophysiology is the oxidative stress, inflammation, alterations in cytokine secretion, and fibrosis.8 Secondary abnormalities include malnutrition and impaired hepatic regeneration.

Epidemiology

Viral Hepatitis

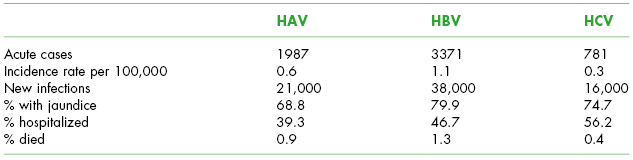

HAV, HBV, and HCV are the most common types, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimating that there are 80,000 new infections each year and an estimated 4.4 million Americans are living with chronic hepatitis, many being unaware of their infection.9 See Table 6.2 for characteristics of acute hepatitis infections.

Table 6.2. Acute Hepatitis Virus Infection Epidemiology (2009) in the United States

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/2009Surveillance/Commentary.htm#bkgrndI.

Risk factors for HAV include close personal contact with an infected person, men who have sex with men, travel outside the United States, illicit drug use, known food-borne outbreaks (fresh produce or food handlers), and contact with a child or employee in a child care center.9 Studies performed in the United States have not shown an occupational risk for health-care workers.3

The prevalence of HBV infection in the United States is 0.4%, with an estimated 0.8–1.4 million persons chronically infected. With the implementation of vaccination programs in 1991, the incidence of new infections in the United States has declined by approximately 82% to 1.5 per 100,000 in 2009.9

HCV is a common problem in the United States with an estimated prevalence of 1.8% (of which approximately 75% are chronic infections), involving approximately 2.7 million people, excluding high-risk groups, such as inmates, institutionalized, and homeless persons.10

In the United States, the prevalence of HDV and HEV are low and HDV is confined to high-risk groups, such as intravenous drug users, while outbreaks of HEV infection have rarely been observed. Vaccination programs for HBV, increased awareness of HDV and its mode of transmission, and better preventive measures (e.g., use of disposable needles) have probably contributed substantially to the decline in HDV in different regions of the world.

ALD

Cirrhosis mortality rates are higher in men than women and higher in Hispanics than Caucasians or African-Americans.11 Cirrhosis mortality is also associated with poverty, and factors such as less nutritional diets, exposure to environmental toxins, and greater stress may aggravate alcohol effects in the liver of disadvantaged populations. Finally, genetic factors influence both patterns of heavy drinking and physiological vulnerability to alcohol effects.8 True prevalence of ALD is difficult to estimate as many adults consume some level of alcohol; however, in the United States in 2009, 30,444 deaths were estimated to have resulted from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, making this the 12th leading cause of death.12

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Incidence and mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma are rising rapidly in the United States because of the increased prevalence of cirrhosis associated with HCV infection in younger patients resulting in up to 4% of patients with cirrhosis developing cancer each year.13 In developed countries, risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients known to have cirrhosis are male gender, age over 55 years, non-Caucasian ethnicity, anti-HCV positivity, and platelet count <75,000.

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

In general, diseases of the liver have several implications for a patient receiving dental care, including potential increased bleeding risk and altered metabolism of medications, requiring dose adjustment or avoidance. The medical history is essential for a correct assessment of the potential risk. The medical history must include questions regarding jaundice, cancer, autoimmune disorders, surgeries, history of alcohol intake, recreational drug use, sexual history, and bleeding tendencies.14 It is important to discuss details of the liver disease with the physician in order to have a better understanding of the patient’s medical status and degree of control. Dentists can encourage chronic alcohol users with ALD to seek counseling and support services, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (see Chapter 16).

II. Medical Management

II. Medical Management

Identification

Patients with chronic liver disease may be able to self-identify on the health history. Liver dysfunction in viral hepatitis and ALD can progress over time requiring identification of current functional status, which is critically important to help gauge coagulation status and ability of the liver to metabolize medications. Patients with acute hepatitis from viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection; autoimmune disorders; and reactions to alcohol, medications, and toxins, require prompt identification of the causative agent to facilitate patient treatment.

Medical History/Physical Examination

Viral Hepatitis

- HAV: The presence and severity of symptoms with HAV infection is related with the patient’s age, including nonspecific and flu-like symptoms, persistent fever, severe pruritus, jaundice, diarrhea, and weight loss. Chronic infection does not occur with HAV.

- HBV: The symptoms of acute HBV infection are nonspecific and include fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, low-grade fever, jaundice, and dark urine.15 Clinical signs include liver tenderness, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Acute HBV infection typically lasts for 2–4 months. Approximately 30–50% of children 5 years and older and adults are symptomatic; infants, children younger than 5 years, and immunosuppressed adults are more likely to be asymptomatic.16 In adults with healthy immune systems, approximately 95% of acute infections are self-limited, with patients recovering and developing immunity.17 Fewer than 5% of adults acutely infected with HBV progress to chronic infection, defined as disease lasting longer than 6 months. A small number (1%) develop acute hepatic failure and may die or require immediate liver transplantation.18

- HCV: The majority of acute and chronic HCV cases are asymptomatic, and patients rarely know when they acquired the infection.10 Nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, vague right upper quadrant discomfort, and pruritus may be noted. HCV infection may progress to cirrhosis with the consequent development of complications such as bleeding, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure. Extrahepatic manifestations of HCV are uncommon and include renal disease, lichen planus, seronegative arthritis, and some neurological conditions.19

ALD

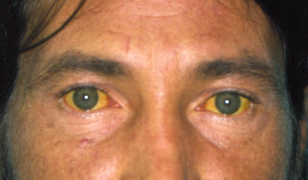

The clinical presentation of ALD can vary from an asymptomatic patient who may have an enlarged liver to a critically ill individual who dies quickly or a patient with end-stage cirrhosis. A recent period of heavy drinking, complaints of anorexia and nausea, and the demonstration of hepatomegaly and jaundice strongly suggest the diagnosis. See Fig. 6.1. Abdominal pain and tenderness, splenomegaly, ascites, fever, and encephalopathy may be present.

Figure 6.1 Jaundiced skin and sclera in a 39-year-old with end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The presence of hepatocellular carcinoma may be unsuspected until there is deterioration in the condition of a cirrhotic patient who was stable. Weakness and weight loss are associated symptoms. The sudden appearance of ascites, which may be bloody, suggests portal or hepatic vein thrombosis by a tumor or bleeding from a necrotic tumor. Physical examination may show tender enlargement of the liver with occasionally a palpable mass.

Laboratory Testing

Viral Hepatitis

HAV

- HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM) test (preferred confirmatory tes/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses