VITAL OR NONVITAL SINGLE DISCOLORED TOOTH

Asingle dark tooth may be either vital or nonvital, and a nonvital tooth may or may not have previously received root canal therapy. A single tooth may be bleached from the inside out, or from the outside in. A third option that is occasionally used is to bleach from both the inside and the outside, with or without closing the endodontic access opening. Typically children’s primary teeth are not bleached. However, when a tooth has been darkened by trauma, and all other pathology has been eliminated, external bleaching may be the most conservative and cost-effective method to lighten it. Other options include pulpotomy and internal bleaching, or using restorative material to mask the discoloration.

Vital Teeth

Vital teeth may become darkened from trauma that causes blood cells from the pulp to invade and stain the dentinal tubules but is not significant enough to cause pulpal death. Another result of trauma can be the partial occlusion or filling of the pulp chamber with dentin, called calcific metamorphosis. Single dark vital teeth in these categories are good candidates for bleaching.

However, there are situations where the teeth are vital, yet are undergoing dramatic pathologic changes such as internal or external resorption. Radiographs and pulp testing are crucial to determining whether bleaching alone is the proper treatment, or more aggressive endodontic therapy or periodontal flap access for treatment is needed. Once clinical and radio-graphic examinations have ruled out an active pathologic condition as the cause of the discoloration, the patient’s esthetic concern of the single dark tooth may be addressed.

As part of the examination, the color of the root and gingiva apical to the anatomic crown should be analyzed. Root dentin does not bleach well, if at all, regardless of the bleaching technique or material employed. Dentin in the anatomic crown of the tooth is different from dentin in the root, and dentin close to the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) is different from dentin near the pulp; they each respond differently to bleaching. Patients should be informed of these limitations, which will also affect the esthetic appearance of a veneer or a full-ceramic crown. No reliable method exists for bleaching the roots of teeth internally or externally.

Once the patient is fully informed of the options and associated limitations, the simplest method to lighten dark teeth from the outside is using tray bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide. The question for the patient is whether they only want to lighten the single tooth, or whether they prefer to lighten all the other teeth as well. Regardless of the bleaching technique employed, the single tooth rarely will be a perfect match after bleaching. However, the single tooth always matches better than before bleaching, whether it alone is bleached, or all the teeth are bleached. Moreover, all other treatment options such as crowns or veneers are still available after bleaching and will have a better appearance when placed on a lighter tooth.

If the patient’s desire is to bleach only the single dark tooth to match the other teeth, a nonscalloped, nonreservoir tray is fabricated. The tooth molds for the teeth on either side of the single dark tooth are removed from the tray. The patient then places the bleaching material in the tray nightly until the single dark tooth either matches the remaining teeth or ceases to change color over a number of days.

If the patient would like all the teeth to be lighter, then a conventional nonscalloped, nonreservoir tray is fabricated. To identify the single tooth, a small x can be placed on the outside of the tray with an indelible marker. The patient then applies the 10% carbamide peroxide in the single tooth mold for a few nights until its shade approximates that of the other teeth, then proceeds with typical bleaching of all the teeth. An alternative method is to start with traditional nightguard vital bleaching of all teeth, then when the natural teeth no longer change color, the patient can continue placing the bleaching material on the single dark tooth alone until it ceases to alter in shade.

While there are also options for in-office bleaching of single dark teeth, the need for multiple visits make this a more costly alternative. Since the number of visits required to achieve maximum whitening is unknown, the patient must be prepared for an ongoing expense as it is determined whether the procedure will work. Also, since most single dark teeth tend to relapse over time, regardless of the bleaching technique used, the tray approach to bleaching allows the patient future options for re-treatment at a minimal expense.

Nonvital Teeth

If a nonvital tooth has not received endodontic therapy, the patient should be examined clinically for pain or drainage and radiographically for periapical radiolucency. In the absence of clinical signs and symptoms of pathology that would require endodontic therapy, the tooth can be bleached from the outside in the same manner as a vital single dark tooth. There are no reports in the literature of any nonvital tooth requiring endodontic therapy as a result of tray bleaching.

There has been a resurgence of interest in internal bleaching of endodontically treated anterior teeth. There was a time in dentistry when it was thought that all endodontically treated teeth needed a post and crown for maximum survival. However, research has shown that anterior teeth have a better survival rate without full-coverage restorations, unless a crown is needed for other reasons. The primary indicator for the long-term survival of an anterior endodontically treated tooth is the amount of remaining dentin, which is compromised by the removal of tooth structure in preparation for a crown. However, posterior endodontically treated teeth generally should receive full-coverage restorations. This different requirement is due to both the anatomic shape of the posterior teeth (multiple roots compared with the single root of an anterior tooth) and the occlusal forces placed on the posterior teeth given their location in the arch.

If the anterior discolored tooth has been treated endodontically, then the first question when choosing a bleaching technique is whether or not the endodontic therapy appears satisfactory. If the root fill of gutta percha is well below the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), the access opening is of sufficient dimension to suggest all the pulp horn remnants were removed, and there is no apparent questionable material in the pulp chamber, then the tooth can be treated externally as described above. However, if there is the possibility of inadequate pulpal debridement in the chamber, the gutta percha extends into the pulp chamber, or there is the possibility of the cement extending into the chamber, then internal bleaching would be the best approach.

In these situations, the endodontic access is reopened and the pulp chamber explored for remnants of tissue. This often requires some removal of tooth structure to gain access to the furthest reaches of the chamber. Once the chamber is cleaned, the root filling material is removed 2 mm below the CEJ. A lining is placed to seal off the pulp chamber and keep the gutta percha in the root canal. The liner material could be a glass ionomer, resin ionomer, intermediate restorative material (IRM), polycarboxylate cement, or zinc phosphate cement; the ideal material is one that bonds to dentin. After the material has hardened, a drop of 10% carbamide peroxide is placed into the chamber, followed by a cotton pellet. The orifice is then closed with a provisional sealing material. The bleaching material is left in place for a number of days, then replaced as many times as needed to achieve the maximum lightening of the tooth. The ease of use of 10% carbamide peroxide and a provisional sealing material results in minimal chair time at the additional appointments, which keeps the cost to the patient relatively low. The minimal concentration of the 10% carbamide peroxide makes it safe for oral use, as well as for handling by the dentist or contact by the patient should the seal be broken.

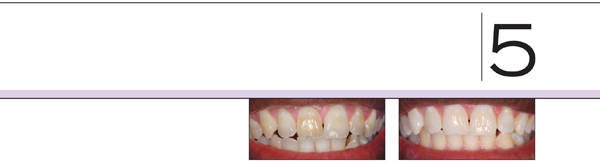

Once the tooth either matches the color of the adjacent teeth or no longer changes color with treatment, it is ready to be restored. It may be best to wait an extra 2 weeks after the last treatment to allow the color to stabilize and the bond strengths to return to normal. Then the internal chamber can be etched, primed, and bonded with composite materials. If the tooth does not match the adjacent teeth, a white opaque composite should be placed internally to further lighten the tooth. The external portion of the tooth can be restored with a shade-matched composite restoration.

Once the tooth has been adequately restored, if there is a need for later bleaching due to relapse, the outside approach is preferable. Any attempt to remove the bonded composite restoration will result in additional removal of dentin, which will weaken the tooth.

Other Bleaching Options

A number of methods have been used to bleach single dark teeth internally. One of the original methods was to place 35% hydrogen peroxide inside the coronal pulp chamber and catalyze it by heat or light to hasten the breakdown of the hydrogen peroxide and potentially accelerate the bleaching process. This process was repeated as many times as necessary until an acceptable result was achieved. A later alternative to this procedure was the walking bleach technique, so called because a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate crystals was sealed in the pulp chamber, and the bleaching occurred while the patient walked out of the office. The advantage of the walking bleach technique was that less chair time was required because the tooth whitening occurred outside of the office over a period of days or weeks. The disadvantages with both of these bleaching techniques are the caustic nature of the 35% hydrogen peroxide and the fact that the results are difficult to predict or control. There is no way to accurately predict the number of treatments required prior to initiating treatment.

A more serious problem with the use of 35% hydrogen peroxide, especially with heat, is the possibility of internal or external resorption, especially in patients with a history of trauma. A relatively limited number of teeth are affected, but when it does occur, it is a significant problem. Although the causes of this resorption are not fully known, a review of the literature indicates a number of possible causes. The most common relationship was in people who experienced traumatic injury. All the cases reported also used the high (35%) concentration of hydrogen peroxide, and heat used with bleaching seemed to be a causative factor for resorption. None of the cases in the literature employed a protective base or liner between the pulp chamber and the gutta percha. Additional possible causes include a deficiency in the cementum, exposure of the cervical dentin to the oral cavity (occurring in approximately 10% of the population), injury to the periodontal ligament triggering an inflammatory response (trauma), and infection sustaining the inflammation.

The first alternative to the caustic 35% hydrogen peroxide was the use of sodium perborate alone. No reports of resorption have been cited with sodium perborate when mixed with water or local anesthetic. However, handling of the material is somewhat difficult. It has been shown that 10% carbamide peroxide is equally effective when compared with the higher concentration of hydrogen peroxide or sodium perborate,/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses