Chapter 5 The General Practitioner’s Pivotal Role in Coordinating MDI Therapeutics

The General Practitioner’s Pivotal Role in Coordinating Therapeutics with Mini Dental Implants

Mini Dental Implants in a General Practice Hospital Residency Setting

Patients with Medical Complexities

Patients with Cardiac Conditions

Patients After Radiation Therapy

Patients with Developmental Disabilities

Everyday Problem-Solving with Mini Dental Implants: A Private Practitioner’s General Practice Retrospective

If There is One Exception to a Rule then There is Proof that the Application of That Rule Must be Guided by Judgement

A Personal Pathway of Historical Experiential Evidence for Incorporating the Use of Sendax Mini Dental Implants into a General Practice

Mini Dental Implants in a General Practice Hospital Residency Setting

Although the restoration of dental implants is becoming more commonly taught in hospital based general practice residency programs, the instruction for insertion of implants has lagged behind. The surgical placement of endosseous implants is usually limited to residents in oral maxillofacial departments or fellows in oral implantology. The scope of implant surgery will be determined by the patient pool and curriculum of that program. The guidelines for accreditation of general practice residency programs include a standard to teach general practice residents to manage implants. Manage is defined as coordinating the delivery of care using a patient-focused approach within the scope of their training. Patient-focused care should include concepts related to the patient’s social, cultural, behavioral, economic, medical, and physical status.” There is no requirement to teach the placement of or restoration of implants. Many programs now teach both placement and restoration. It is currently a luxury often seen as an attractive privilege by general practice residency applicants.

The continuing success of small-diameter dental implants as a treatment modality has become increasingly clear.10,13,8,15,14,5 The mini dental implant (MDI) system has provided a cost-effective, time-efficient, patient-satisfying option that can be easily integrated into a general practice. This supports the philosophy that implantology is a science driven primarily by the restorative phase and not the surgical phase. The surgical aspects of implants are a means to an end: the restoration of form and function for the patient. Any implant therapy needs to have the patient’s specific needs addressed in the treatment plan.9 What better group to be trained in the placement of implants than the general practitioner who will be doing the final restorations? The number of general practitioners placing implants has increased over the last decade.4 Mini dental implants are a minimally invasive treatment option that serve as a rational place for general practitioners to begin their implant experience. The philosophy of a general practice residency is to expose the residents to all areas of dentistry. This provides a springboard from which they can begin to mold their own treatment philosophy. They can acquire proficiency in many areas and still retain the insight into what to refer to specialists. The positive result for our profession of general practice residency training is that more general dentists are trained to treat patients with more complex problems.3 As we see in all areas of dentistry, the general practitioner is seeking further training to achieve a higher level of skill in any given field, and implant dentistry is an increasingly significant part of that learning equation.

The residents are asked to locate a lower lateral or central incisor, single tooth replacement case as their first patient experience. Often these cases are simple with few problems and give the residents the basics they need to treat larger more complex cases. Before treating patients with the MDI, the residents must complete training in the surgical protocol for their placement. This consists of either participating in a one day training course or having the same lecture material presented as part of the regular curriculum during the residency. The goals are for each resident to plan treatments and treat one or more single tooth replacements and one or more implant overdenture cases. There is no limitation on the clinical experience available to the residents in this area.

Resident Case Selection

When selecting a first MDI case for restoration, the residents are encouraged to limit as many variables as possible. As their experience and training progress, more complicated patient profiles and procedures are selected. Hospital dental clinics fabricate a large number of complete dentures. This is usually due to the patient populations’ financial limitations and dental history. For the same reasons, these patients are usually not offered or, if offered, able to accept conventional dental implants. Others have avoided anything but dentures due to fear of surgery, fear of pain, or, again, for lack of finances. Moreover many of the patients are kept from surgical implant therapy by their medical status. Often consultations from cardiology, hematology, and many other medical specialties advise against invasive procedures on certain patients. These cases are where MDIs shine as an option. As a first case, the residents are asked to select patients with few complicating medical conditions (ASA 1 to ASA 2) (Box 5-1).2

BOX 5-1 American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status Classification System

ASA 1: a normal healthy patient

ASA 2: a patient with mild systemic disease

ASA 3: a patient with severe systemic disease

ASA 4: a patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life

ASA 5: a moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the procedure

ASA 6: a brain dead patient whose organs are being harvested for donation purposes

Our patient population is vast and diverse. Any hospital service will draw patients from within the institution as well as from the community. The patients are varied both medically and socioeconomically. Over time we have become a center for small diameter implants, with regard to both their placement and their restoration. For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on the medical and dental parameters of our patients. We are faced daily with many different situations that require a complete understanding of the patient’s past medical history and how it will affect the proposed treatment plan.

Patients With Cardiac Conditions

The hospital dental clinic setting is a common place for referrals of patients seen for other services in the hospital. Many patients have some form of cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis and hypertension make up 40% of all organic heart diseases.9 Recent protocols for patients in cardiac rehabilitation who have medication releasing stents dictate that they must stay on oral anticoagulants for the rest of their lives. In some cases, these patients are treated with a combination of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies.12 These patients are at risk during surgical procedures for excessive bleeding. They are at times poor candidates for large incisions and flap reflections. Due to the vascularity, cutting osteotomies into medullary bone causes bleeding. Increasing the diameter of the osteotomy opens more vasculature to increase bleeding. Wide full thickness mucoperiosteal flaps causes bleeding as well. Both procedures can cause changes in crestal bone that can adversely affect implant healing.9,11 A far better option for this group of patients is the simplified nonsurgical protocol of the MDI. Because no flap is created, bleeding is minimal. The hole through the soft tissue made by the pilot drill is only 1.1-mm wide. The pilot hole is taken one-third the length of the implant (in moderately dense bone) and removed. The implant is then placed into the hole and engages bone. As the implant is progressed to full length, it is not removing bone as an osteotomy would, but rather compressing the bone around it. This tamponade stops medullary vessels from bleeding. This also contributes to its initial stabilization. This generally stops any bleeding from bone, and the procedure is completed with little or no postoperative bleeding.

Patients After Radiation Therapy

Another common referral to our dental clinic is from the departments of Medical and Radiation Oncology. These patients often present after surviving various forms of cancer and having had radiation and chemotherapy. The bone and soft tissue will be affected directly. The associated medical issues and compromised immune system place them in a fragile category in which conventional implant therapy to replace missing teeth or to stabilize a removable prosthesis is not an option. Radiation therapy has much longer lasting consequences that chemotherapy. Patients who have had radiation therapy directly to the mandible or maxilla due to oral and head and neck cancers or metastasis to the head and neck region are particularly fragile. These patients are often faced with few options for improvement of quality of life in the area of their oral health, both in form and function.6 Often radiation to the head and neck results in destruction of the salivary glands, both major and minor. Complete denture retention relies heavily on oral moisture to develop “suction.” Without this moisture denture retention suffers and denture function is severely impaired. With the concurrent loss of stability, denture sores are common and heal poorly due to decreased tissue vascularity. The minimally invasive protocols for MDIs are again of great benefit in these cases. Using the MDI to stabilize complete upper and lower dentures gives these patients the ability to function with their dentures normally.

For patients who have received radiation therapy to the mandible or maxilla, conventional implants would not be an option. The process of healing relies on the formation of a stable clot from healthy bleeding bone. Higher doses of radiation therapy decreases the ability of bone to heal properly. Radiation therapy also results in compromised vascularity of the overlying, soft tissue. Large, full thickness flaps show poor healing and are at risk for breakdown, exposing underlying bone. The margins of a surgical flap and the cut bone walls of a conventional osteotomy will have poor healing. The MDIs are placed into the pilot hole, and they are self threading and compress the bone as they engage it. After the pilot hole there is no cutting of bone when using the MDIs, and the compromised vascularity will not adversely affect the healing.1

Patients After Chemotherapy

Many types of cancer are treated with a combination of radiation and chemotherapy. Although radiation therapy may not affect the prospective implant surgical sites, if chemotherapy is used in conjunction to treat the cancer, the systemic effect is a concern. The severe neutropenia that accompanies chemotherapy places a patient at much greater risk for postoperative complications. The best option of course is to wait a prescribed amount of time before beginning any elective dental surgery. The healing of the soft tissue, response of bone to surgical trauma, and the risk for infection will benefit from waiting.7

Patients With Developmental Disabilities

If a patient presents with a small edentulous area a greater number of implants can be placed and used to retain a fixed prosthesis. The nonsurgical protocol lends itself to the treatment of patients for whom a larger more invasive and longer implant surgery is not ideal. In these cases, a laboratory processed long-term provisional bridge is the restoration of choice. A processed temporary is serviceable for repair or modification, can be removed if needed for evaluation, and replaced at reasonable cost.

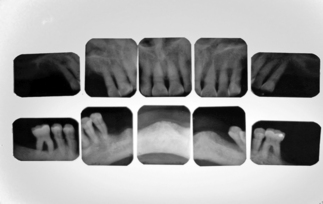

Radiographic Studies

Other critical diagnostic information can be determined by close inspection of the radiographs. Mainly, anatomical landmarks and possible limitations to implant placement can be visualized. In some cases the quality of the bone at the implant site can be assessed before placement from the appearance of the bony architecture on radiographs. Of course the overall health of the bone is evaluated to assure there are no lesions, malignancies, or other pathologies present.

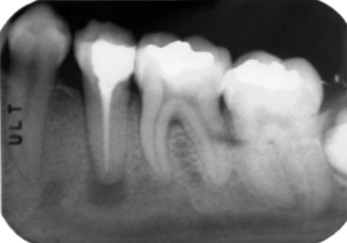

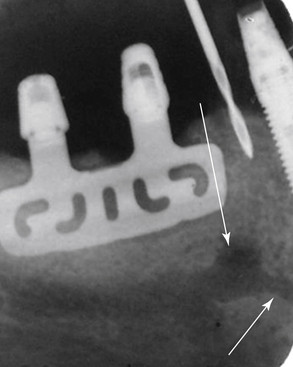

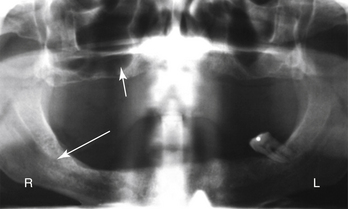

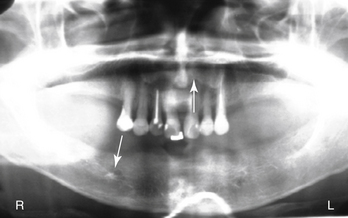

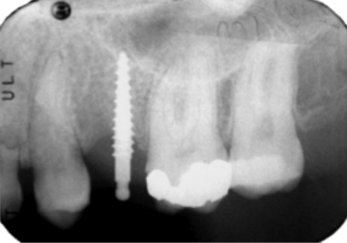

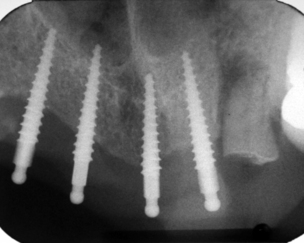

In most cases, the main anatomical structures that must be identified on radiographs and subsequently avoided during placement are the anterior loop (Figures 5-1 and 5-2), the inferior alveolar canal (Figure 5-3), the mental foramen and the floor of the nose (Figure 5-4), and the floor of the maxillary sinus (see Figure 5-3). There are occasions when engaging the floor of the maxillary sinus is beneficial, resulting in bicortical stabilization and enhanced initial stability of the implant. Radiographic examples of this bicortical stabilization can be seen in Figures 5-5 and 5-6.

Clinical Exam

After radiographs have been reviewed, a clinical evaluation of the proposed implant sites needs to be done. The needs for evaluation for a removable retention case or a fixed prosthesis is not very different. The size, height, width, and location of the bone at the implant site needs to be evaluated and correlated with the radiographic surveys. Combining these two diagnostic tests is the best way to get a clear picture of what will be encountered when placing any implants. Aside from manual palpation of the bony ridge, the use of bone calipers or other thickness measuring devises that can be used to gauge bone width are very useful. The practitioner can create a very accurate bone width map, which can assure proper implant placement for success.

After all the diagnostic data are collected, the case can be planned effectively and accurately.

Treatment Planning

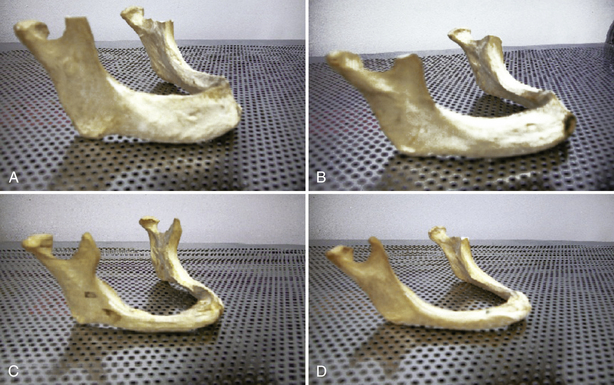

The patient’s expectations discovered during the interview must be taken into consideration when finalizing the treatment plan. The starting point for the patient and the final goal should be clearly understood by the dentist. To illustrate this, we can look at a lower denture wearer. Patients who have complete lower dentures soon after they loose their teeth usually have more residual alveolar ridge, and their dentures will function and be retained differently than patients who have been wearing dentures for many years. In Figure 5-7 we see a clear illustration of the changes of the mandible over time.

Case Discussions

Let us begin the case discussions with a routine overdenture case. The cases presented in this chapter are representative of those found in our residency program as well as cases that present to a private practice. The incredible versatility of these implants allows a wide range of uses.

Case Discussion 1

A 77-year-old man presents with a chief complaint of loose teeth. He claims during the interview that “I think I need full plates.” After radiographs and complete diagnosis, it was determined that he did in fact need all of his teeth removed. His medical history included controlled hypertension and arthritis, with medications for each. He had no limitations other than walking slowly with a cane. From the radiographs, it was clear that lower denture retention would be an issue (Figure 5-8a). The option of MDIs was discussed and, after a complete informed consent, the case was scheduled.

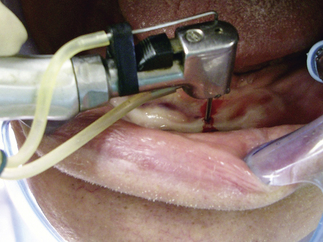

The patient’s remaining teeth were extracted, and complete maxillary and mandibular dentures were fabricated. The patient wore the dentures for 2 weeks and was seen for adjustments during that time. He presented for the implant placement visit as directed. His medical history was again reviewed and no changes were noted. He also reported that the dentures were comfortable but loose. Local anesthesia was given. Bilateral mental blocks and local infiltrations were given using lidocaine 2%, 1:100,000 epinephrine (Figure 5-8b).

After the surgical protocol, the sites were marked and the pilot hole was drilled to one third the length of the implant (Figure 5-8c).

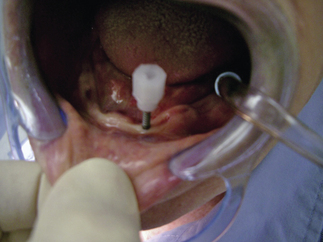

The implant was then delivered to the site still attached to the plastic carrier (Figure 5-8d).

After the implant was engaged in bone, the carrier was changed for the finger driver. The implant was then advanced until it was tight with the finger driver. At this point, the finger driver was changed for the winged wrench driver, which provided much greater torque and allowed the implant to be taken to full length. In some cases, the winged wrench gets too tight to turn and the ratchet driver is used to completely seat the implant; there was no need for the ratchet in this case. The two most posterior implants were placed, and the center one was placed last (Figures 5-8e and 5-8f).

The denture was attached with metal housings and O-rings according the prescribed protocol.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses