Chapter 5

Restoration of the Periodontally Treated Tooth

Conservation of tooth structure while achieving a return to form and function with a lasting prosthetic restorative procedure are the goals of the restorative dentist. The approach taken with direct or indirect restorative procedures is aimed at the recapture of oral health and long-term stability, through the use of materials that will replace missing or damaged tooth structure without violation of biological tenets or compromise of mechanical principles.

Because emphasis is placed on conservation in the modern concepts of tooth preparation, many of the G. V. Black principles of cavity preparation have been put aside (1). Improvements in dental materials and evidence-based procedures have shown minimally invasive treatments to be meritorious. It is a well-accepted concept that naturally occurring tooth structure is superior to its artificial substitutes. Therefore, tooth preparation decisions are made that tend to preserve tooth structure, protect vital pulpal structures, avoid violation of the periodontium, and reestablish healthy contacts with the neighboring teeth.

The concepts of retention and resistance form must be emphasized while mastering various tooth preparation designs for partial and full-coverage restorations, as well as the unique preparation requirements for ceramics and CAD/CAM materials.

A partial-coverage approach is employed where possible, and the taper of the preparation is kept to a minimal convergence angle. Tooth reduction follows the external anatomy of the tooth, and should be uniform and appropriate for the materials chosen to replace the prepared tooth structure. Aesthetic demands must be taken into account. Overreduction, whether occlusally or axially, will jeopardize the integrity and health of the pulpal tissues and will require sophisticated laboratory skills in the fabrication of the resulting prosthesis. Optimal tooth reduction maximizes aesthetic results and culminates in a durable, long-lasting restoration. This objective is achieved by the proper tooth preparation and margin design.

An acceptable restorative margin would have a margin design that results in the smallest cement gap or space possible, that achieves the desired aesthetics for the situation, and that falls into an area free of recurrent disease that is easy to maintain. An ideal margin demonstrates the following characteristics:

- It is easy to prepare.

- It is easy to see in the impression and on the prepared tooth.

- The prepared margin results in a dies that can be easily read.

- The preparation depth is sufficient to result in adequate metal thickness or porcelain bulk to avoid distortion and to achieve aesthetics appropriate for the given situation.

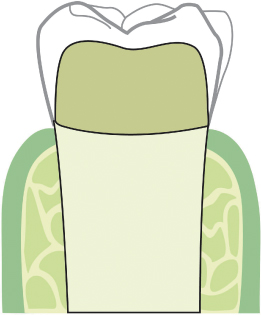

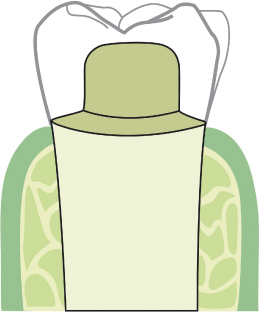

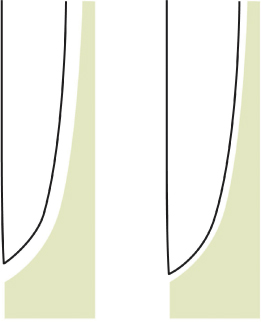

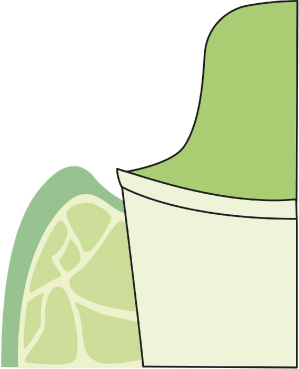

The three major preparation geometries are: the feather, the chamfer, and the shoulder. These preparation designs are distinguished by their unique marginal geometries (Figs. 5.1–5.4).

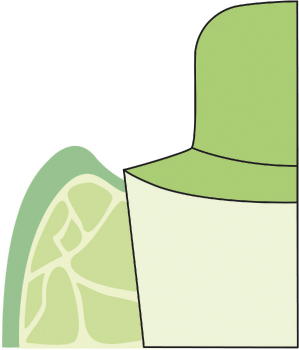

Fig. 5.1 A diagrammatic representation of a feather-edge margin.

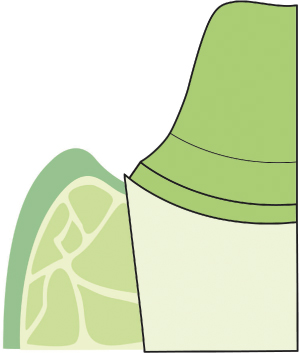

Fig. 5.2 A diagrammatic representation of chamfer margin.

Fig. 5.3 A diagrammatic representation of a shoulder margin.

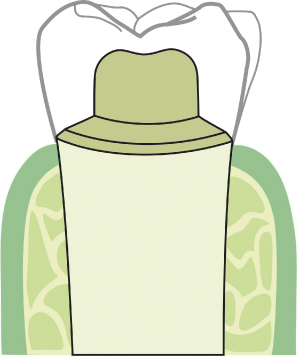

Fig. 5.4 Another view of a feather margin in the seating process.

The Feather

The feather margin preparation design conserves the most tooth structure of all preparation designs. Margin preparation is made with a tapered bur. Axial reduction is minimal, as the goal of the feather edge margin preparation is conservative removal of tooth structure and maximization of the retentive nature of the preparation through the use of a minimal taper. This margin preparation is difficult to accomplish because it is difficult to see. The distinct boundary between the prepared tooth structure and the unprepared tooth structure can seem obscure.

The feather edge margin is indicated in those situations where the need for tooth structure conservation and a retentive preparation are crucial. A situation where the structure of a tooth to be restored is short incisogingivally will benefit from this style of preparation. The minimal taper of the design adds retentive form to the preparation. The feather edge margin design is also employed when the teeth being prepared are long and narrow (Figs. 5.5–5.8). The more aggressive margin preparations to be discussed, with the exception of the light chamfer, are contra-indicated in such situations as they require too great a degree of tooth structure removal at the cervical aspect of the tooth and would compromise the integrity of the pulpal tissue. This preparation design is employed in areas of severe recession, when the preparation margin must be placed on root structure. For obvious reasons, the preparation needs to be minimal and be placed supragingivally. The profile of the finished restoration must be flat, and emergence from the gingival to the incisal aspects of the crown must be devoid of plaque trapping contours. This area is sensitive to additional attachment loss and must be protected during the impression making process by avoiding invasions of the sulcus with retraction media. The restoration should finish with a polished margin that has minimal plaque retentive properties.

Fig. 5.5 A view of the model after impression is poured in stone.

Fig. 5.6 A tooth preparation with a feather-edge margin has been carried out. Note the long parallel preparation, which is necessary for retention.

Fig. 5.7 A view of the crown for the prepared tooth.

Fig. 5.8 The crown is delivered.

The feather edge preparation is employed in areas where the furcation has been exposed, or where there has been excessive recession and the root surface has to be prepared. The minimal axial tooth reduction of the feather edge design both prevents the development of tooth preparation undercuts and avoids overpreparation of thin residual tooth structure. Such margins are placed supragingivally so as to be more easily examined and managed.

While the feather edge margin design has the advantages of being minimally invasive and improving the retention and resistance form of a tooth preparation, the difficulties one experienced in the laboratory phase of restoration makes this a margin preparation to be employed only in specific circumstances.

The feather edge is a difficult design for the laboratory to work with in the fabrication of a restoration. The tooth preparation, with a minimal distinction between prepared and unprepared tooth structure, is difficult to capture in an impression. This visual obscurity translates to the dies, where the margin is more difficult to see. If the margin is misread and is thought to extend more apically than it does, there is the potential for the restoration to fail to seat on the tooth. Conversely, if the margin is read as short of the actual finish line, the resulting restoration will seal the prepared area just short of the true finish line, which can be acceptable.

The laboratory will also be challenged in the fabrication of a restoration using the lost wax method, as the wax at the marginal area is thin and easily broken or distorted.

The Chamfer

The chamfer may be the best known and most popular preparation design in clinical practice, as it is easy to place and can be readily identified on the tooth and in the impression. The resulting die is easy to read. There is a distinct boundary between prepared and unprepared tooth structure, which may be predictably captured in a wax pattern. The chamfer preparation has sufficient depth to ensure that the resultant wax pattern and castings are stable and can be handled without distortion.

The internal anatomy of the chamfer preparation is obtained with a round-ended bur, as rounded internal angles are the preferred design. The rounded internal angle design has the favorable attribute of distributing forces rather than concentrating them, an attribute that is important when porcelain is added to the framework for a porcelain metal restoration. The inclined nature of the semicircular design ensures positive seating of the restoration and a closed marginal gap. The chamfer preparation design is aesthetic when placed in healthy periodontal environments, 0.5 mm into the sulcus of anterior teeth

The chamfer has a versatility not seen in any of the other preparation designs. Because the preparation mirrors a round-ended bur, the diameter of the bur used will dictate the axial depth of the preparation. Therefore, in the instance where the preparation needs to be minimal, a thin round-ended diamond bur is selected. In a situation where a deeper axial preparation is required to allow maximum thickness of porcelain, a larger diameter bur is selected.

However, a weakness of the chamfer preparation is also contained in the round-ended bur that creates the preparation. The ideal margin design requires a preparation that is actually less than the diameter of the bur, which can be technically difficult for the operator to accomplish. If the depth of the preparation penetrates beyond the diameter of the bur, a reverse curve is created in the marginal area, resulting in a tooth “lip,” which will hamper the fabrication of a stable die margin or wax pattern, and will create a casting that will not seat completely. The occurrence of this enamel lip is greatest when axial penetration increases. Therefore, the smallest error will have the most profound affect (Fig. 5.9).

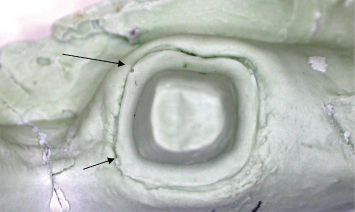

Fig. 5.9 An example of overpreparation resulting in a reverse curve or lip.

In such a situation, the margin edge demonstrates unsupported enamel, which is not a stable situation and cannot be accurately reproduced by the laboratory. The use of a bevel eliminates this problem and improves the fit of the restoration. The subcategory of beveled margins is of great advantage with the heavy chamfered margin design.

The Shoulder

The shoulder preparation is performed with a tapered, flat-ended bur, resulting in an axial wall that tapers in an occlusal direction from a flat gingival cervical floor. The preparation is easy to distinguish, as there is a distinct boundary between prepared and unprepared tooth structure. The shoulder preparation has sufficient depth to ensure that the resulting wax pattern and castings are stable and can be easily handled without distortion.

The shoulder preparation needs to be placed at or slightly coronal to the marginal gingiva in order to achieve clarity of the finish line. The blunt cervical margin, when prepared to an adequate axial depth, can be restored in metal, ceramometal, or porcelain. The marginal geometry of the shoulder design makes it accepting of all porcelain margins, with the aesthetic advantage of allowing placement of a bulk of porcelain. Increased strength and designed optical properties are attained through such placement of bulk material at the cervical aspect of the tooth. This fact is crucial, as the cervical aspect of a prepared tooth is an area where opaque show through may betray an otherwise aesthetic restoration as being inadequately reduced.

The draw back to the shoulder design is that it is an aggressive and difficult preparation to execute. The marginal finish must be smooth and free of areas of unsupported enamel. When preparing a tooth, marginal placement angulates from the buccal in an occlusal direction through the interdental spaces, and terminates on the lingual aspect of the tooth. Creating a continuously flat surface in a 360-degree tooth-bound space requires a certain level of skill.

Another drawback to the shoulder design is the difficulty in capturing it in an impression. In circumstances where there is little space between the marginal tissue and the finished margin, marginal material tears and inaccuracies within the impression may occur. The resultant dies will reflect these inaccuracies. Because there is a flush right-angle fit of restorative material to tooth surface, any distortions will result in an open margin or a failure of the restoration to seal.

Considering the context of the distortions inherent in impression materials, die fabrication materials, and restorative materials, this concern is a considerable impediment to overcome (Fig. 5.10).

Fig. 5.10 A view of the die of a shoulder preparation without a bevel. Note the errors that are present.

To overcome these shortcomings and improve preparation marginal design, a subcategory has evolved that incorporates the use of a beveled margin. Such a bevel has great application with the heavy shoulder margin design.

BEVELED MARGINS AS A SUBCATEGORY

Marginal areas that will be required to support porcelain need to have a design that permits the laboratory to fabricate a substructure with sufficient strength to prevent distortion in the fabrication of the restoration, flexure at delivery of the restoration, and destabilization of the porcelain at the porcelain metal interface. The use of the bevel as a subcategory in the shoulder or heavy chamfer design combines the positive aspects of these two major preparation design categories, resulting in aesthetics, increased retention, and ease of impressioning (Fig. 5.11).

Fig. 5.11 A diagrammatic representation of a heavy chamfer with a bevel.

All porcelain margins represent another possible solution to this problem. However, to ensure an adequate and stable margin, a preparation that provides for adequate thickness of porcelain at the margin also creates a marginal gap, which represents an inherent compromise.

The best solution to aesthetic margin placement is the use of metal at the tooth restoration interface, due to the accuracy of the casting and design of the metal at the margin to support the porcelain. The margin design of choice has traditionally been a heavy chamfer, which provides for the required thickness of material at the margin for stability of the restoration’s margin, and porcelain placement with an improved tooth restoration gap over the all-porcelain margin. This design also has a rounded axial gingival contour, which is more favorable to the placement and support of porcelain. Due to the semicircular nature of the margin design, the fit is optimized and marginal gap is minimized by concept of inclined planes. This concept states that surfaces that meet on inclined planes will be closed at some point along that incline.

The shoulder design will allow for adequate marginal dimensions to place metal and porcelain, or all porcelain, margins. However, because the final marginal design is at right angles to the long axis of the tooth, the fit of such a margin is often less accurate than desired, resulting in an unacceptable margin gap (Figs. 5.12, 5.13).

Fig. 5.12 A diagrammatic representation of a shoulder preparation.

Fig. 5.13 A diagrammatic representation of a shoulder preparation with a bevel preparation.

To overcome this drawback of the shoulder design, and improve the fit of the restoration, a bevel is placed 0.5 mm into the sulcus. The aesthetics of the porcelain at the margin, coupled with the fit of a beveled margin hidden in the sulcus, has proven to be a successful solution to this quandary.

Such a bevel has also been applied to the heavy chamfer margin design taking advantage of the curved internal angles of the preparation, which favor the placement and support of porcelain, and the aesthetics achieved by hiding the margin in the sulcus. The use of a bevel adds to the retentive nature of the preparation. In areas wher/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses