Chapter 5

Periodontal Diagnosis in Young Patients

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to outline the principles of diagnosis and key features of periodontal conditions that the dental practitioner may come across when caring for children, adolescents and young adults.

Outcomes

Most of the periodontal problems that the young patient may experience are plaque-induced, but some uncommon conditions are not. After reading this chapter, the practitioner should understand how to reach a periodontal diagnosis in the young patient and should be able to diagnose the principal periodontal diseases that can affect children, adolescents and young adults. The reader will also understand how important systemic risk factors such as smoking, poorly controlled diabetes or stress can influence the presentation of periodontal diseases in the young.

Principles of Periodontal Diagnosis

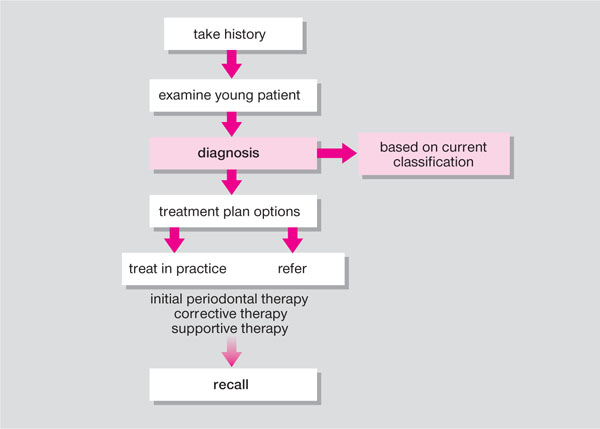

A periodontal diagnosis is reached after consideration of findings from the history (Chapter 3) and examination (Chapter 4) and requires an awareness of the current classification of periodontal diseases as discussed in Chapter 1 (Fig 5-1).

Fig 5-1 Stages in periodontal patient management: diagnosis.

Based on the current classification system of the 1999 International Workshop, the diagnosis should fall within one of the main classification categories or its subdivisions (see Table 1-1):

-

Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases.

-

Non-plaque-induced gingival lesions.

-

Chronic periodontitis.

-

Aggressive periodontitis.

-

Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease.

-

Necrotising periodontal diseases.

-

Abscesses of the periodontium.

-

Periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions.

-

Developmental or acquired deformities and conditions.

This chapter will cover the key clinical and radiographic diagnostic features of the principal periodontal diseases in categories A, C, D and F – I that affect children, adolescents and young adults. Category B is covered in Chapter 6 and category E is covered in Chapter 7.

Gingival Diseases

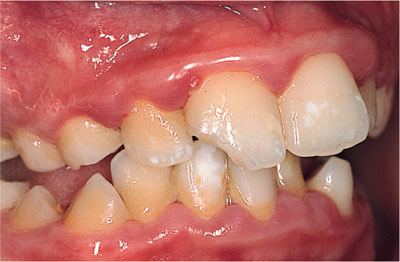

The most common form of gingivitis is dental plaque-induced gingivitis, with key diagnostic features are shown in Box 5-1. This may present with or without local risk factors such as supra- and subgingival calculus (Fig 5-2) or mouth breathing (Fig 5-3).

Fig 5-2 Plaque-induced gingivitis in a 10-year-old Asian girl. Supragingival calculus visible at buccal margins of LL1, LL2 and erupting UL4.

Fig 5-3 A twelve-year-old who breathes through his mouth, with lack of lip seal (incompetent lips). Note the gingiva is more inflamed anteriorly than posteriorly due to lack of the protective effects of saliva.

Box 5-1

Diagnostic Features of Plaque-induced Gingivitis

Plaque present at gingival margin

Change in gingival colour, contour

Increased gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) from sulcus, and increased sulcular temperature

Bleeding from margin of gingiva on provocation, e.g. probing

No attachment loss

No bone loss

Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) = 1 and/or BPE = 2 are compatible with diagnosis of gingivitis

False gingival pockets ≥4mm may be present due to gingival swelling

False pockets should be distinguished from true periodontal pockets ≥4mm

Clinical and histological changes are reversible on removal of plaque

Plaque-induced gingivitis can develop on a reduced periodontium following resolution of previous periodontitis where pre-existing attachment loss or bone loss may be present

Other forms of plaque-induced gingivitis include those associated with systemic risk factors, e.g. pregnancy (Fig 5-4) or drug-induced gingival overgrowth (Fig 5-5a,b).

Fig 5-4 Pregnancy-related gingivitis in a young patient.

Fig 5-5 (a) Drug-induced gingival overgrowth in a teenage boy taking ciclosporin and nifedipine following a heart transplant. (b) Drug-induced gingival overgrowth reduced when the two drugs were replaced with tacrolimus and a non-calcium-channel blocking drug.

Chronic Periodontitis

Incipient Chronic Periodontitis

Since the transition from reversible gingivitis to incipient chronic periodontitis can affect a sizeable proportion of teenagers (Chapter 1), Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) screening should be undertaken at the initial consultation in this age group and at recall visits (Box 5-2, Fig 5-6). Radiographs should be reviewed for bone loss, especially if serial views of intraoral films are available. Horizontal bitewings are particularly useful for assessing crestal bone levels in this age group.

Box 5-2

Diagnostic Features of Chronic Periodontitis

Incipient chronic periodontitis

Age of onset can be in adolescence (13–14 years)

Interproximal clinical attachment loss of 1–2mm (commonly seen on maxillary first molars, mandibular incisors), associated with presence of plaque, subgingival calculus

Pockets 4–5mm (screening BPE = 3)

Bone loss no more than ~0.5mm over an 18-month period (bitewing radiographs typically show horizontal pattern of bone loss)

If BPE = 4 or BPE = * in adolescence, suspect aggressive periodontitis (see below)

Established chronic periodontitis

Presence of interproximal clinical loss of attachment (CAL)

True pocket formation ≥4mm (screening by BPE = 3 or BPE = 4)

Bone loss evident on radiographic examination, typically, horizontal pattern of bone loss although vertical bone loss may be present at some sites

Possible (variable) presence of drifting, inflammation, mobility, recession and furcation defects (BPE = *)

Slow to moderate progression and exacerbations

Can be further classified according to extent of CAL (localised ≤30% sites affected; generalised >30% affected) and severity (slight = CAL 1–2mm; moderate = 3–4mm, severe ≥5mm)

Plaque control inadequate; supragingival calculus frequent finding

Variable subgingival plaque microbiota, e.g. P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, A. actinomycetemcomitans

Destruction consistent with presence of local factors, e.g. subgingival calculus

Modifying factors include local predisposing factors, poorly controlled diabetes, stress and smoking

Fig 5-6 Basic Periodontal Examination screening of one of the index teeth in a 17-year-old Asian girl.

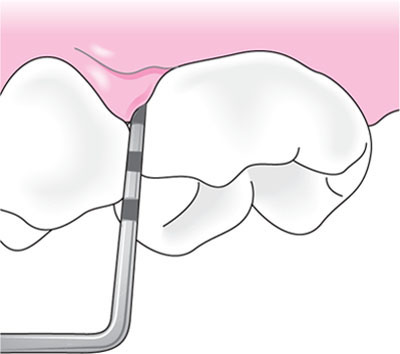

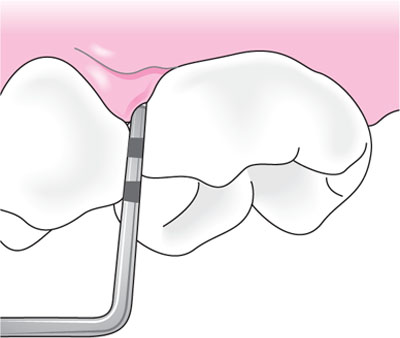

If there is any doubt as to whether pockets are true or false, the presence of clinical loss of attachment should be determined. In this age group, the “one-stage technique” is useful for measuring small amounts of clinical loss of attachment (1–3mm): the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) is located by tactile sensation and the distance advanced by the probe apically from this position is noted until the clinical attachment level (i.e. base of the pocket) is reached (Figs 5-7 and 5-8).

Fig 5-7 A 19-year-old patient with incipient chronic periodontitis.

Fig 5-8a Measuring the clinical attachment level: periodontal probe tip located at CEJ on tooth. CEJ located by tactile sensation.

Fig 5-8b Measuring the clinical attachment level: periodontal probe tip located 1mm apical to CEJ at clinical attachment level, indicating loss of attachment of 1mm.

Chronic Periodontitis

With increasing age, the cumulative effects of attachment loss, pocket formation and alveolar bone loss progressively and slowly increase the prevalence, extent and severity of chronic periodontitis. Exacerbations can occur at times of stress, or resumption of a smoking habit.

Smoking-related Chronic Periodontitis

Young patients who smoke show more severe clinical attachment loss, pockets and radiographic bone loss than same-age peers with similar plaque levels as explained in earlier chapters (Chapters 1 and 3). Typical diagnostic features are the pale, fibrous gingiva, which have less tendency to bleed on probing due to the vasoconstrictive effects of tobacco components. Maxillary anterior and palatal surfaces are adversely affected and anterior recession may be a presenting feature. Nicotine staining is readily detectable and often increased supragingival calculus formation is seen. These features form the basis of a diagnosis of smoking-related chronic periodontitis (Fig 5-9). Smoking can just as readily influence the severity of the presentation of aggressive forms of periodontitis.

Fig 5-9 A lifetime’s exposure to cigarette smoking beyond adolescence and young adulthood into middle age is associated with smoking-related chronic periodontitis. Note the pale fibrous gingivae, anterior recession, nicotine staining and supragingival calculus.

Aggressive Periodontitis

Because of the rapidly destructive nature of this condition, early diagnosis is especially important so that therapy can be instigated as soon as possible. There are two forms: localised and generalised.

Localised Aggressive Periodontitis

The localised form of aggressive periodontitis can present around puberty, and specifically affects first molars and incisors (unlike incipient chronic periodontitis that can affect these and other sites). The key diagnosti/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses