Chapter 5

Muscle-related Problems

Aim

This chapter discusses referred muscle pain, the most common reason, after dental causes, for patients to complain of pain in the orofacial region.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the practitioner should be able to recognise and assess patients for referred muscle pain.

Case Presentation

-

Complaint. A 35-year-old male presented with a nine-month history of mild, dull, aching pain in the left maxillary molar teeth. The pain radiated to the left temple, causing headache, and to the left ear. He also felt slightly swollen in the upper cheek area and had a mild tingling feeling in the skin of the cheek, together with an occasional feeling of twitching in the area. The symptoms were most pronounced on waking in the morning and were increased with chewing. He was not aware of jaw joint clicking. The pain level was assessed as 6, at its worst, on a 1–10 visual analogue scale (VAS) scale. The patient had been referred to an ENT consultant for the ear pain and a feeling of reduced hearing, with a sense of the ear being blocked.

-

Clinical examination. On examination, the patient had a good range of mouth opening at 43 mm interincisally, with slight deflection to the left side. He described a mild ache in both cheeks, more pronounced on the left side, with wide opening. Palpation revealed mild tenderness over the left temporomanibular joint (TMJ). The left masseter and temporalis were both very tender. The headache tended to be replicated with temporalis palpation and the tooth and ear pain with masseter palpation. There was pronounced incisal wear of the anterior teeth and some faceting visible on the canines and posterior teeth. Soft tissue changes were observed in the lateral border of the tongue and buccal mucosa.

-

Treatment. The patient was advised to avoid tooth contact during the day and to do some simple jaw-stretching exercises to reduce muscle tension. At a one-month review, the patient reported a reduction in pain levels during the day but was still waking in the morning with high levels of pain. A hard acrylic stabilisation splint was provided for night-time wear. At a six-month review, the patient was essentially pain free. He continued to wear his splint for a further six months, by which time he had no tenderness in any muscles and all symptoms had resolved.

Introduction

Pain of muscular origin – myogenous pain – is the most common source of non-dental pain that dentists encounter. This pain is most often described as a non-specific, dull, aching sensation of mild to moderate intensity, with a feeling of pressure or tension in the affected area. As this is a non-descript type of pain, it is easy to see how it can be confused with pain of dental origin. Although the pain is typically vague in location, it is not uncommon for the patient to be adamant that a tooth is responsible for the pain. The prudent practitioner should, in the absence of a dental problem, resist the temptation to provide any treatment: no diagnosis – no treatment.

It is not uncommon to hear of pain derived from the structural components of the jaw referred to as “TMJ pain”. This is effectively a misnomer, as the term TMJ merely refers to the joint not a condition. The more meaningful term, temporomandibular disorder (TMD), describes a problem that involves either some aspect of the joint or of the muscles of mastication – or more commonly a combination of the two. This chapter will review the problems associated with the masticatory musculature. The most common problems tend to be characterised by pain.

The Masticatory Musculature

The function of the masticatory musculature is to open and close the jaw and maintain jaw posture. The latter is required as gravity tends to pull the jaw downwards when we are in an upright position. Muscle tonus is required to stabilise the jaw in its resting position, with the teeth separated by a few millimetres: the freeway space. Muscles in the neck and back have a very important role to play in maintaining posture. Some are also involved in jaw posture. Postural muscles are more likely than other muscle groups to be involved in pain conditions, as they are made up of a type of muscle fibre that is designed to cope with long-term, low-level tonus or tension. For this reason, muscle pain tends to be associated with postural muscles.

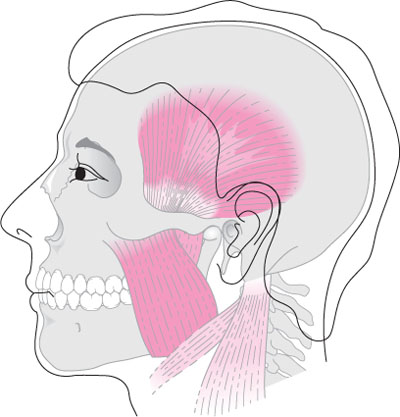

The muscles involved in jaw closure are masseter, medial pterygoid and temporalis. These are the, muscles primarily involved in TMDs (Fig 5-1). The jaw is unique amongst the musculoskeletal systems of the body in that the masticatory muscles are the only ones to have a fixed, unyielding end-point to their activity; this is the the intercuspal position (ICP).

Fig 5-1 The masticatory muscles.

The muscle primarily involved in opening the jaw is the anterior digastric. This is a relatively small muscle, reflecting the level of work required of it. To a lesser extent, the lateral pterygoid muscles may be involved in both opening and closing.

The physical make-up of the masticatory muscles reflects the type of activity required of them. This activity involves a combination of relatively brief forceful movements, as required in chewing, and a constant low-grade activity required of the jaw-closing muscles to maintain jaw posture. Parafunctional activities, including jaw clenching, biting and chewing habits and bruxing, tend to be problematic for the masticatory muscles as they involve sustained high-level activities that the muscles were not designed to undertake.

Muscle Pain

Common terms in muscle pain disorders are:

-

myositis: inflammation of muscle tissue

-

myalgia: pain in a muscle

-

myogenic pain: pain originating in a muscle

-

myofascial pain: regional muscle pain associated with trigger points

-

trigger point: hyperirritable spot, usually found within a taut band of skeletal muscle, that is painful on compression and gives rise to referred pain.

The pain originating in muscles is know as myogenic pain and is generally non-inflammatory, despite its possible improvement with the use of antiinflammatory agents, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The analgesic properties of these drugs allow a return to normal function by reducing pain levels and thereby facilitating healing. There is, at times, an inflammatory cause for myogenic pain; such pain is referred to as myositis. It is most commonly seen as a result of direct trauma to a muscle, for example injury to the medial pterygoid muscle following needle penetration during the administration of an inferior dental block.

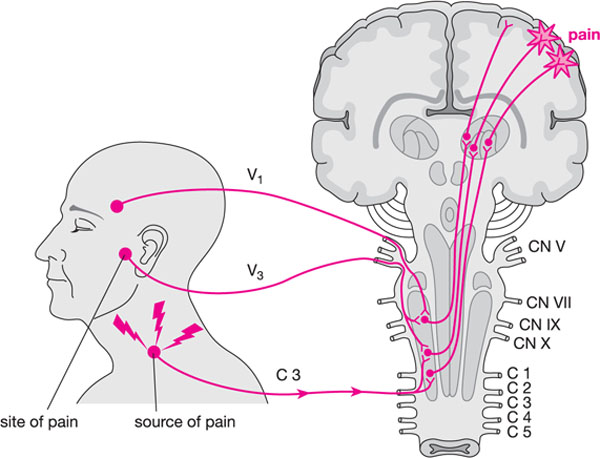

In myofascial pain, the pain is referred. The patient may, therefore, perceive the pain at the point of referral rather than at the point of origin. This can cause difficulty for the clinician in that no reason for pain may be noted on examination of the site of the pain, but palpation of a distant muscle may reveal tenderness (Fig 5-2). The point of origin of the pain may feature a small nodular area or trigger point.

Fig 5-2 Pain referral from a cervical muscle to the area of the left temporomandibular joint. (Courtesy of JP Okeson, Bell’s Orofacial Pain, Chicago: Quintessence, 2005.)

Muscle Pain and Headache

Headaches in patients with muscle pain is often, but not exclusively, referred pain from the temporalis muscle. Cervical muscle problems may give rise to/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses