Chapter 5

Managing Local Risk Factors

Aim

Clinical examination of patients often reveals the presence of local risk factors for periodontal disease. This chapter aims to provide information on how to manage local risk factors as part of the overall treatment plan.

Outcome

After reading this chapter, the reader should:

-

be aware of the more common local risk factors that may impact on periodontal disease progression and provision of treatment

-

understand better the impact of trauma from occlusion on the periodontium, and how to manage occlusal trauma

-

understand the importance of furcation involvement in multi-rooted teeth

-

be better informed on how to manage specific local predisposing factors.

Definitions

The concept of multi-level risk assessment was described in Understanding Periodontal Diseases: Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures in Practice. Briefly, risk assessment should be undertaken at the patient level, the mouth level, the tooth level and the periodontal site level. In order to identify local risk factors for periodontal disease, a thorough clinical and radiographic examination should be undertaken (Chapters 7, 8 and 9 of Understanding Periodontal Diseases).

Local risk factors can be defined as factors associated with the teeth and supporting tissues that may initiate or predispose to periodontal disease. They are difficult to classify, but can be broadly defined under two major groups:

-

anatomical risk factors

-

iatrogenic risk factors.

However, certain risk factors may fall into both groups, such as trauma from occlusion, which may result, for example, from malaligned or over-erupted teeth (anatomical risk factors) or poorly contoured restorations (iatrogenic risk factors). For the purpose of this chapter, trauma from occlusion will be discussed separately from the two major groups.

Trauma from occlusion

Trauma from occlusion can be divided into two major categories:

-

traumatic incisor relationships that result in direct damage to the periodontal tissues

-

occlusal trauma arising from occlusal interferences that may affect both healthy (primary occlusal trauma) and periodontally-involved (secondary occlusal trauma) teeth (see Decision-Making for the Periodontal Team).

Traumatic Incisor Relationships

A complete overbite onto the gingival soft tissues can result in extensive gingival recession with the soft tissues being sheared away from the root surface during function. The nature of the incisal relationship can be classified (Box 5-1). From the periodontal point of view, the Akerly class II and III incisal relationships are most significant (Figs 5-1 and 5-2). With the stripping of the gingiva, loss of attachment occurs, most frequently in relation to the palatal aspect of maxillary incisors and the labial aspect of the mandibular incisors. Akerly class I and IV incisal relationships typically present with minimal, if any, effect on the periodontal supporting tissues.

Box 5-1 The Akerly classifications of traumatic incisor relationships

Class I Lower incisors impinge onto the palatal mucosa, posterior to the palatal gingival margins of the maxillary anterior teeth Class II Lower incisors occlude onto the palatal gingival margins of the maxillary anterior teeth Class III A deep traumatic overbite (class II division 2 incisal relationship) with shearing of the mandibular labial gingiva Class IV Lower incisors occlude with the palatal surfaces of the upper incisors, leading to tooth wear by attrition

Fig 5-1 Akerly Class II incisal relationship. Note the recession in relation to the palatal aspects of the maxillary incisors.

Fig 5-2 Traumatic overbite (Akerly Class III incisal relationship). Notice how the maxillary incisors are impinging on the labial gingiva of the lower incisors (see also Fig 5-3).

Predisposing factors for traumatic relationships include:

-

a severe class II, division two incisor relationship

-

loss of posterior support, particularly if associated with over-closure of the remaining anterior teeth

-

poorly designed anterior restorations with no occlusal stops, leading to over-eruption of the incisors

-

incomplete orthodontic treatment.

Frequently, deep localised recession defects will develop which are difficult to keep clean, leading to significant accumulation of plaque and the development of gingival inflammation and periodontal breakdown (Fig 5-3). The first line of treatment is to re-establish gingival health by undertaking non-surgical periodontal therapy and by providing intensive oral hygiene instruction (OHI). Single-tufted brushes may be particularly useful to clean into the recession defect. A useful preliminary treatment option is to provide a soft splint to prevent further damage to the periodontal soft tissues, particularly in those patients with a night time bruxing habit.

Fig 5-3 When the patient opens their mouth, the consequences of the traumatic overbite can be seen. There is localised gingival recession affecting the mandibular incisors and shearing away of the gingiva, in particular, in relation to the lower left lateral incisor. There is also evidence of attritive toothwear affecting the left lateral incisor.

Once periodontal health has been re-established, definitive treatment options may be explored. Often, these may be intensive and complicated, and referral for advice and treatment planning by a specialist restorative dentist is likely to be required. Treatment options include:

-

Provision of posterior support to re-establish the correct occlusal vertical dimension and eliminate the destructive incisal contacts.

-

Restoration of the anterior teeth to provide occlusal stops, e.g. by the provision of adhesive metal palatal shims (Fig 5-4), composite resin restorations, or carefully designed crowns. A “Dahl approach” may be required to increase space anteriorly for the provision of these restorations. The classic Dahl appliance is rarely used nowadays. Palatal composite restorations that have been carefully contoured are equally effective (Fig 5-5).

-

Overlay appliances may be used as a long-term alternative to the soft splint (Fig 5-6).

-

More complex cases may require orthodontic therapy, orthognathic surgery, or segmental or full-mouth rehabilitation.

Fig 5-4 Adhesive palatal shims and anterior bridge-work to rebuild the anterior dentition and provide a stable occlusion.

Fig 5-5 Palatal composite restorations used as an alternative to a Dahl appliance to increase the occlusal vertical dimension and provide occlusal stability.

Fig 5-6 Overlay partial denture to prevent further trauma from occlusion and provide occlusal stability.

Occlusal Interferences

Occlusal interferences and premature contacts can arise when the occlusal morphology and position of teeth are altered following the placement of restorations or after orthodontic treatment. Interferences may lead to occlusal trauma that manifests clinically as:

-

increasing mobility and migration of the teeth

-

pain

-

tenderness to percussion

-

tooth fracture

-

faceting of cusps

-

bruxism

-

temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD).

Occlusal trauma arising from occlusal interferences can be divided into:

-

primary occlusal trauma in which a lesion results from application of excessive occlusal forces to a tooth with normal periodontal supporting structures (Fig 5-7).

-

secondary occlusal trauma in which the lesion affects the periodontium of a tooth with reduced periodontal support because of current periodontal disease (Figs 5-8 to 5-10). The greater the amount of periodontal support that has been lost, the more significant the role of occlusion becomes as a co-destructive factor.

Fig 5-7 Widened periodontal membrane space as a result of a traumatic occlusal interference in a tooth with normal periodontal supporting structures.

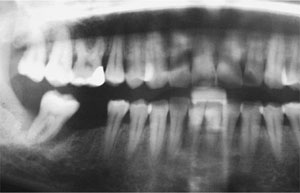

Fig 5-8 Crater defect around the lower right molar, which has pre-existing periodontitis and a traumatic occlusal interference (see also Figs 5-9 and 5-10). The bone loss has extended to the apex of the tooth. Notice that there is generalised moderate to severe chronic periodontitis affecting the rest of the dentition.

Fig 5-9 Clinical appearance of the traumatic occlusal interference (case illustrated in Fig 5-8). Note the deflective contact between the buccal surface of the lower right molar, and the palatal cusp of the upper right second molar.

Fig 5-10 As the patient closes fully into the intercuspal position, the lower right molar is deflected lingually. This “jiggling” force affecting a tooth with pre-existing periodontitis has resulted in exacerbation of the destructive events in the periodontium, and is an example of secondary occlusal trauma.

The designation of “primary” or “secondary” occlusal trauma is principally for diagnostic purposes. The changes that occur in the periodontium as a result of trauma from occlusion are the same whether there is normal or reduced periodontal support. The diagnosis is often confirmed radiographically. Primary occlusal trauma results in a widened periodontal membrane space (PMS) and early “funnelling” but normal alveolar bone height (Fig 5-7), whereas secondary occlusal trauma presents with obvious alveolar bone destruction and a characteristic crater-defect surrounding the affected tooth (Fig 5-8).

The lesion of occlusal trauma usually arises following a succession of opposing tension and pressure forces on the periodontium (so-c/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses