Chapter 5

Gingival Enlargements – Localised

Aim

This chapter aims to provide the practitioner with a visual guide to swellings that arise locally within the gingiva, including the free and/or attached gingiva.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter the reader should have knowledge of which types of localised gingival swellings are common or uncommon, be able to identify the key clinical features of localised gingival enlargements and formulate a differential diagnosis for a localised gingival swelling. The reader will also be able to decide which lesions can be managed within their practice and which need to be referred for specialist advice.

Table 5-1 lists the gingival enlargements discussed in this chapter and highlights which are common or uncommon and when the condition may be managed in general practice or should be referred.

| Lesions | Category | Sub-Category | Incidence | Manage/ Refer |

| True epulides | Fibrous epulis | common (60% of epulides) | manage | |

| Vascular epulis | Pyogenic granuloma Pregnancy epulis |

common (30% of epulides) | manage | |

| Multiple/disseminated pyogenic granuloma | uncommon | refer | ||

| Giant cell epulis/ granuloma | Peripheral | uncommon (10%) | refer | |

| Central | uncommon | refer | ||

| Lesions presenting as epulides | Congenital epulis | uncommon | refer | |

| Viral warts | Condyloma acuminatum | uncommon | refer | |

| Verruca vulgaris | uncommon | refer | ||

| Neurofibroma | uncommon | refer | ||

| Appliance-induced hyperplasia | common | manage | ||

| Other gingival swellings | Abscess | Periodontal | common | manage |

| Gingival | uncommon | manage | ||

| Stitch | uncommon | manage | ||

| Localised trauma | uncommon | manage/ refer | ||

| Histiocytosis-X | Unifocal (solitary eosinophilic granuloma) Multifocal (Hand-Schuller-Christian syndrome) Progressive/disseminated (Letterer-Siwe disease) |

uncommon | refer | |

| Haemangioma | uncommon | refer | ||

| Tumours | Malignant lesions | Kaposi’s sarcoma | uncommon | refer |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | uncommon | refer | ||

| Metastatic tumours | uncommon | refer | ||

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | uncommon | refer | ||

| Benign lesions | Reactive osteoma | uncommon | manage | |

| Lesions associated with PTEN mutations | Cowden’s syndrome Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome Proteus syndrome |

uncommon | refer |

The Epulides

Gingival epulides are benign localised enlargements of the gingival tissues. They are predominantly hyperplastic lesions of the gingival connective tissues, which develop following chronic irritation. The source of irritation may vary and examples include:

-

Ledged or prominent subgingival restorations.

-

Subgingival calculus.

-

Clasp arms from removable appliances.

-

Impaction of a foreign body subgingivally.

Many lesions may present as epulides, but only three true forms are described:

-

Fibrous epulis.

-

Vascular epulis (pyogenic granuloma or pregnancy epulis).

-

Giant cell epulides (peripheral or centrally arising).

The term epulis means ‘on the gum’, and all true epulides have a common pathogenesis, which involves the body attempting to heal an area of inflammation through the formation of granulation and fibrous tissue, whilst the inflammatory stimulus remains. Therefore, true epulides are histologically similar and show variable features of chronic inflammation, immature vascular tissue (granulation tissue) and collagen deposition. The only exception is the congenital epulis.

The Fibrous Epulis

Clinical appearance

Fibrous epulides present as pink, firm enlargements of the interdental gingivae (Fig 5-1). They may be sessile or pedunculated and similar in colour to the surrounding tissues unless they become inflamed. Ulceration can arise, leading to a yellow, fibrinous surface exudate. They are normally firm in consistency, do not blanch, and pitting of the surface may be seen due to the insertion of collagen bundles beneath. Calcification or ossification may arise within some lesions, when the term ‘calcifying or cementifying fibrous epulis’ is used. The behaviour and treatment of the latter is the same, but recurrence is reported to be more common.

Fig 5-1 A fibrous epulis UR 3 related to chronic irritation from subgingival calculus acting as a plaque retention factor.

Clinical symptoms

Often symptom-free and predominantly cause aesthetic concerns. Rarely they can lead to tooth migration and irritation to the overlying soft tissues (e.g. lip).

Aetiology

As for all epulides (see previous text).

Involvement of non-gingival sites

None.

Differential diagnosis

-

Vascular epulis.

-

Giant cell granuloma.

-

Benign osteoma of underlying alveolar bone.

-

Denture induced hyperplasia.

-

Gingival cyst.

-

Neurofibroma.

-

Connective tissue tumour (see chapter 11).

-

Metastatic tumour.

Clinical investigation

Excisional biopsy for histopathology with careful gingival recontouring. Lesions consists of a core of highly cellular fibroblastic and granulation tissue covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which may or may not be ulcerated. There are varying degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration, mainly with plasma cells.

Management options

If large, referral is advisable. Surgical excision followed by recontouring of the gingivae to form a marginal complex that lends itself to easy cleansing. Thorough subgingival debridement is performed to remove potential aetiological agents, e.g. calculus, foreign body, plaque. Apply a pressure pack, to maintain the interproximal zone patent during the healing phase. Chlorhexidine mouthwash is advisable during this period, and the patient should be reviewed after seven days for dressing removal and prophylaxis. At this stage the patient should resume careful interproximal plaque control. Lesions may recur if the cause of the irritation persists.

The Vascular Epulis

Clinical appearance

Vascular epulides mainly arise in the anterior part of the mouth and usually, the labial aspect. They are soft, normally pedunculated lesions with a narrow base which, when associated with pregnancy (Fig 5-2), can progress throughout the gestation period. Commonly they occur in the second or third trimester and may have a very red/granular surface that is prone to haemorrhage (spontaneous or as a result of trauma). The surface may ulcerate, leaving a yellow, fibrinous coating (Fig 5-3).

Fig 5-2 A pregnancy epulis affecting UR1 and UL1 teeth and demonstrating a classical dumb-bell or hourglass shape between the incisors.

Fig 5-3 A vascular epulis affecting LR5. The surface has ulcerated due to trauma from the opposing teeth.

Clinical symptoms

Bleeding to touch or when brushing, poor aesthetics and discomfort on pressure.

Aetiology

The pregnancy epulis and pyogenic granuloma (Fig 5-4) are histologically identical. The term ‘pyogenic granuloma’ is a historical one, since it was thought (incorrectly) that the lesion was an inflammatory response to infection with pyogenic bacteria. Lesions develop for the same reasons as other epulides, but vascular changes characterise the inflammatory response rather than fibrosis. Pregnancy-associated lesions are generally associated with subgingival plaque or calculus.

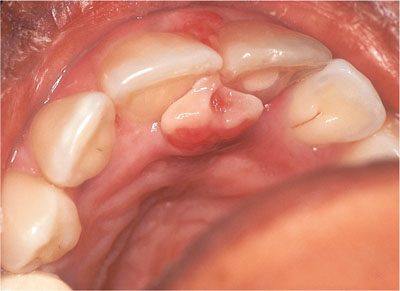

Fig 5-4 A pyogenic granuloma (vascular epulis) arising UR45 area due to poorly contoured subgingival temporary dressings.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

None.

Differential diagnosis

-

Giant cell granuloma.

-

Denture induced hyperplasia.

-

Fibrous epulis.

-

Kaposi’s sarcoma.

-

Gingival cyst.

Clinical investigation

Presumptive diagnosis can be made on appearance, but definitive diagnosis requires an excision biopsy. Lesions comprise a mass of vascular spaces within a fine, connective tissue stroma. There may be solid layers of uncanalised endothelium or many thin-walled immature vessels and the surface is often ulcerated, with an inflammatory infiltrate beneath the ulceration. Histologically, the pregnancy epulis is regarded as a pyogenic granuloma arising during pregnancy.

Management options

Intensive oral hygiene instruction and scaling under local anaesthesia reduces the vascular nature of the lesion and may lead to its resolution. However, excision is often necessary and recurrence rates are high. Good vasoconstriction is essential from a local anaesthetic and an electrosurgery or bi-polar diathermy should be on hand. The area should be thoroughly scaled and a pressure dressing applied. It is common for the lesion to return, therefore excision is preferable post-parturition. Many resolve spontaneously postpartum. The non-pregnancy associated pyogenic granuloma is excised in a similar manner. However, the cause, such as defective restorations, should be identified and removed.

Multiple/Disseminated Pyogenic Granulomata

Clinical appearance

This is an extremely rare condition. The case shown in Figs 5-5 and 5-6 presented in a seven-year-old boy. Appearance is of multiple vascular exophytic lesions, which present as disseminated vascular tumours with a relatively short natural history. Lesions have a fibrinous exudate at their surface, similar to solitary pyogenic granulomas. Satellite and intravenous pyogenic granulomas may develop at the same time as the primary lesion or may occur after attempted treatment of the primary lesion. Lesions may be grouped or eruptive and disseminated in nature.

Fig 5-5 Multiple pyogenic granulomas in a seven-year-old boy affecting the palatal aspects of his anterior teeth.

Fig 5-6 The same boy as in Fig 5-5 with multiple lesions affecting the lower incisor teeth.

Clinical symptoms

There is gingival bleeding when the tissues are subject to light trauma from brushing or eating. Spontaneous bleeding is also reported.

Aetiology

Trauma, hormonal influences, viral oncogenes, underlying microscopic arteriovenous malformations, and production of angiogenic factors have all been implicated. However, i/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses