Diagnosis of endodontic problems

The nature of endodontic diagnosis

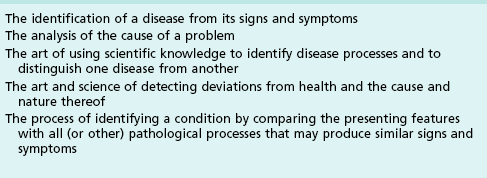

Diagnosis is the art of systematic use of verified or unverified information to derive the identity or cause of a problem; it involves objective and intuitive processes. The clinician will often call upon objective processes but also (sometimes unknowingly) relies heavily on intuitive processes. Intuition is an inner faculty not well defined by scientific disciplines but is well recognized in other areas of knowledge. The best example of its power is given by the ability of the patient to intuit a cause without any scientific grounding in the problem. Such a process alone is not sufficient for a clinician but supplements objective, learnt processes. Diagnosis has been defined in a variety of ways (Table 4.1). It is one of the more intellectually stimulating parts of clinical practice, which brings out the detective zeal in the clinician.

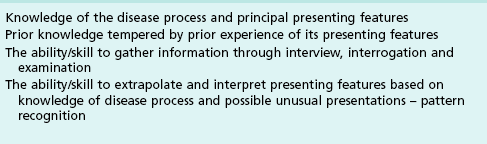

The process of diagnosis is a complex one, involving several diverse aspects. The identification of a disease is based on knowledge of its pathology, natural history and its presenting features (Table 4.2).

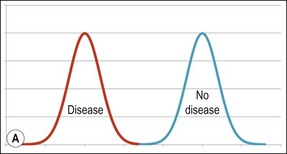

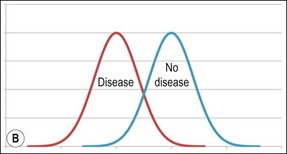

The presentation of any disease is subject to normal variation, which may be depicted by its Gaussian distribution, classically described as a bell curve (Fig. 4.1).

Fig. 4.1 Distributions for normal and disease states without (a) or with (b) overlapping presentations

The variations are a function of genetically expressed biological differences between patients and the anatomical conjunction within which the disease manifests. Dentists are normally taught the “central tendency”, that is, the commonest presentation; it being too difficult and complicated to teach each of the variations that may present in reality. A practical clinical interpretation to augment this theoretical knowledge is, therefore necessary and is acquired through supervised clinical practice, where a teacher shows the links between clinical manifestations and the embedded theoretical picture of histopathology and physiology. Subsequent independent practice upon graduation requires vigilant tracking of the outcome of all diagnostic decisions; that is, did their judgement solve the patient’s problem. The problem of coincidental resolutions can only be overcome through dedicated, conscientious, active, repeat experience, which allows a definitive pattern of outcomes to be consolidated. The dentist, thus through a process of mind application and intuition learns to recognize when their decision was correct and when the favourable outcome may simply have been a coincidence. It stands to reason that a peripatetic dentist who does not work for long in any one place is unlikely to develop such integration and consolidation of diagnostic insight (see Table 4.2). Through the gathering of such experience, the use of basic pathological principles, together with the aid of intuitive processes, the dentist is able to develop the ability to recognize the “outliers” that present at the extremes of the Gaussian distribution. To reach such a status requires considerable active experience.

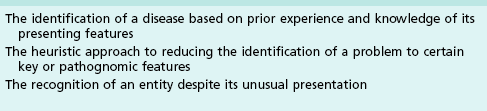

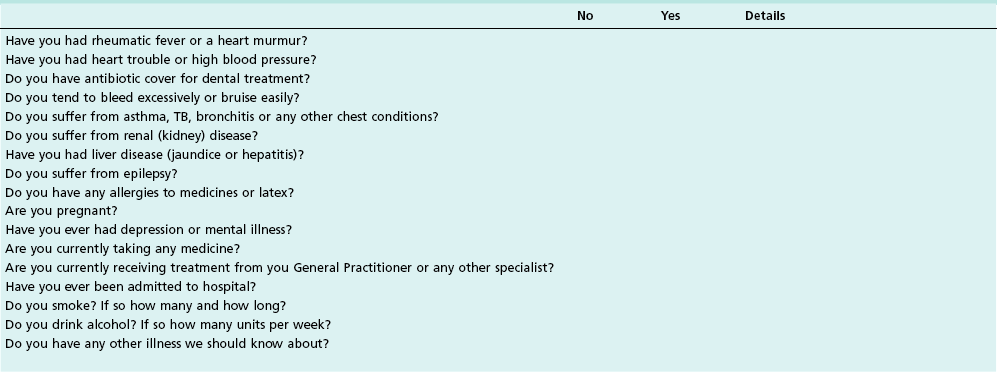

In the interests of efficiency, experienced dentists may learn to apply a heuristic approach, whereby they reduce the identification of a problem to certain key or pathognomonic features (Table 4.3). This can work if applied with due diligence and caution but is a trap for misdiagnosis if applied without a proper foundation.

The nature of endodontic problems

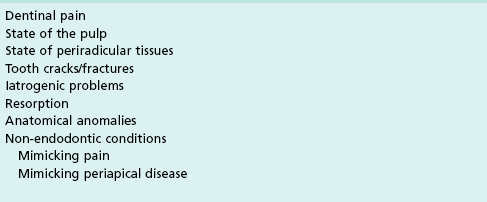

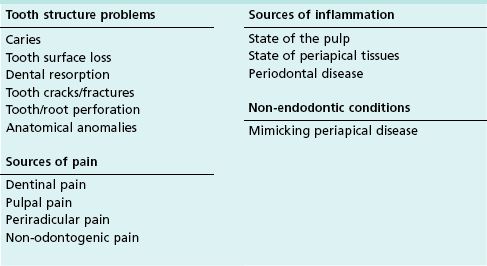

The clinician will be examining the patient for a relatively small variety of disorders in an endodontic assessment, yet the process seems complex and confounds many dentists. The prime reason for this is that there is considerable overlap in the presenting descriptions of various conditions and it remains for the discerning clinician to tease out subtle discriminating differences. In many cases, the patient seeks treatment because of overt signs and symptoms, some of which have an obvious diagnosis, but many conditions are silent (sign and symptom-free) and discovered only by chance on routine examination. Common disorders, which may be revealed during an endodontic assessment are given in Table 4.4.

Patient assessment

The nature of presenting complaints

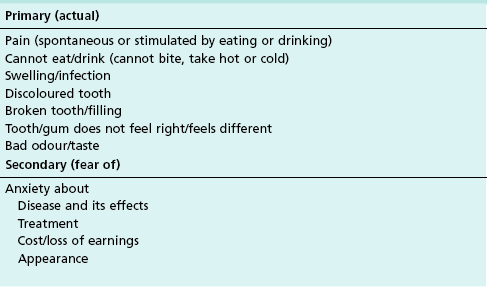

The nature of primary presenting complaints from endodontic patients is diverse and can embrace pain, discomfort, aesthetics, infection, and function. These are also sometimes confused with, or superimposed by, various anxieties (Table 4.5).

The clinician’s task is to identify and propose relevant and appropriate solutions for the patient’s problems. The complicating aspect in this task is that the search for a single direct cause–effect relationship between a presenting feature and cause (Table 4.6) is confounded by the many sources of the presenting complaint (Table 4.7). The clinician must therefore appreciate the potential decision-tree and be ready to filter the received information through their diagnostic sieve to derive the single or as may be the case, multiple superimposed causes.

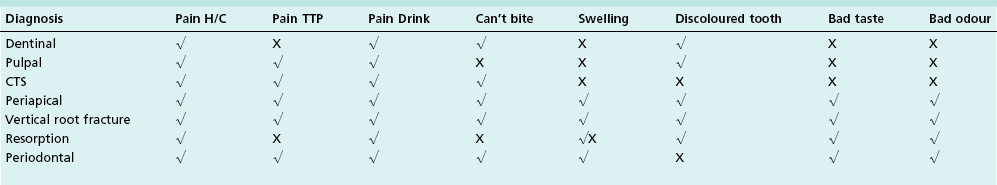

Medical history

A medical history is taken to find out whether the patient has any health problem or is taking medication that could affect the treatment. The most convenient way of recording such information is to use a checklist that is kept in the patient’s file, such as that shown in Table 4.8.

The initial consultation is most effectively carried out beside a desk with both patient and clinician seated; patients find this less stressful than immediately being asked to sit in a dental chair (Fig. 4.2).

Clinical examination

Extraoral

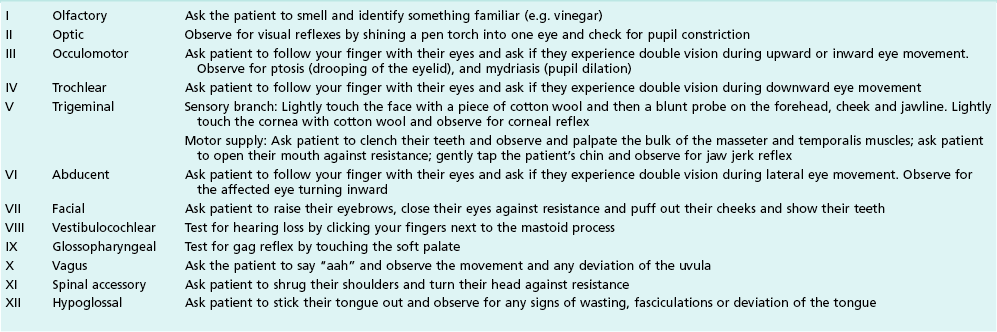

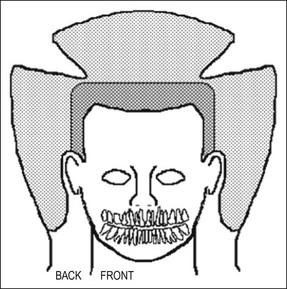

Extraoral examination is carried out for facial swelling, asymmetry, tenderness of muscles of mastication and the temporomandibular joints, nerve responses (Table 4.9) and the presence of enlarged lymph nodes. Facial swelling is best viewed from above the patient (Figs 4.3, 4.4).

Ease of oral access

An assessment should be made of the ease of access, particularly to the posterior part of the mouth. As a general guide, if a patient’s mouth will not open wide enough to allow two fingers to pass between the incisors, root-canal treatment of the molars may be compromised (Fig. 4.5). Some patients, with small mouths, particularly the elderly, find it difficult to keep their mouth sufficiently wide open for long periods, using a mouth prop, which they may relax upon during treatment, does help (Fig. 4.6).

Soft tissue examination

The soft tissues, consisting of the cheek mucosa, tongue, floor of mouth, palate, sulcular fold, and those overlying the alveolus should all be assessed, after wiping with gauze, by direct visual observation for signs of inflammation, sinus tract openings, induration, swellings, fibroepithelial growth, ulcers or discoloration (Fig. 4.13).

The purpose of tactile stimulation is to determine whether the tissues are allodynic, hyperalgesic, tender or normal. A light touch may be applied, such as with a cotton bud to see if pain is elicited, indicating neuropathic changes. An increasing degree of force is applied by finger palpation to determine the presence of tenderness, which the patient is asked to confirm. The areas of altered sensation should be mapped on a diagram in the records (Fig. 4.14).

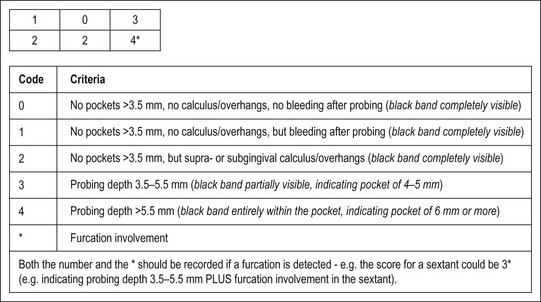

Periodontal examination

A general periodontal examination should be performed to characterize the periodontal status as part of the overall treatment plan, resulting in a basic periodontal examination (BPE) score (Fig. 4.15). The purpose is to determine and segregate any problems arising from marginal periodontal problems. More specifically, it is essential to exclude local, deep, isolated probing defects, signalling tooth anomalies, fractures, or sinuses (see Chapter 12).

A part of this assessment includes a determination of any periodontal overloading, manifesting in tooth mobility, fremitus or tooth drifting. Mobility of a tooth is assessed by placing a finger on one side and pressing with an instrument or another finger from the other (Fig. 4.16). The amount of movement is judged in relation to an adjacent tooth. Mobility may be graded as slight (grade 1), which is considered normal, moderate (grade 2), or extensive (grade 3) in a lateral or mesiodistal direction, combined with vertical displacement in the alveolus (Table 4.10).

Table 4.10

Miller classification (tooth mobility)

| Class I | Tooth can be moved less than 1 mm in the buccolingual or mesiodistal direction |

| Class II | Tooth can be moved 1 mm or more in the buccolingual or mesiodistal direction No mobility in the occlusoapical direction (vertical mobility) |

| Class III | Tooth can be moved 1 mm or more in the buccolingual or mesiodistal direction Mobility in the occlusoapical direction is also present |

Tooth examination

Transmission of a powerful light through teeth will show interproximal caries and (of particular interest in endodontics) cracks, infractions and fractures. Extraneous light is reduced; the fibreoptic light placed next to the neck of the tooth and moved along its surface. The light will not pass across the fracture line due to reflection, so the part of the tooth nearest to the light is bright and that beyond the fracture remains dark: Figure 4.17 shows this effect. Figure 4.18 shows a mandibular first molar with a coronal restoration removed – a fracture line is visible in the distal wall.

At the extremes of the pressure stroke, the tooth may begin to deform allowing any cracks to open. This, in a vital tooth, is detected as a sharp dentinal pain, which may be felt on pressure application or release. In a non-vital tooth, a periodontal sensation, rather than a dentinal sensation is evident. Since cracks may be localized to individual cusps, this examination is enhanced by the use of a hard or viscous substance (such as a Burlew disc, rolled rubber dam, wooden stick, an inlay seater or tooth slooth®), which facilitate isolation of increased pressure to individual cusps (Fig. 4.19).

Using an impact force rather than graduated pressure, allows a different sort of assessment as the tooth moves differently in the viscoelastic periodontal ligament. Gentle tapping with a finger (both vertically and laterally) and then with an instrument will locate a tender tooth but it is a harsher test and usually gives a slightly different result to a pressure test (Fig. 4.20). If ankylosis of a tooth is suspected, tapping with an instrument handle in the long axis of the tooth will confirm the diagnosis: an ankylosed tooth has a distinctive high-pitched ring.

Pulp testing

Electric pulp tester

An example of a pulp tester, the Analytic Technology Endo Analyser, is shown (Fig. 4.21a). This instrument has a dual function acting as both a pulp tester and an electronic apex locator (EAL). When used as a pulp tester, a pulsating stimulus is produced starting at a low value, which increases automatically. The pulse amplitude of the stimulus begins at 15 volts and rises to a maximum of 350 volts.

Fig. 4.21 (a) Unit has a dual function both as a pulp tester and an apex locator; (b) pulp tester applied to buccal surface of tooth isolated with strips of rubber dam (toothpaste used as a conducting medium); (c) patient controls the pulp tester; (d) special tip for pulp testing beneath crowns; (e) pulp testing beneath crown

Pulp testing technique

The test and control teeth should be dried and isolated with cotton wool or rubber dam (see Fig. 4.21b), the latter applied as small strips placed between the teeth. Contacts may also be isolated by inserting acetate strips between teeth. A conducting medium must be used – the one most readily available is toothpaste. The pulp tester is applied to the middle third of the tooth, avoiding contact with the soft tissues, and any restorations. A lip electrode is placed over the patient’s lip. If the pulp is vital the patient describes feeling a sensation which is variously described as tingling, vibration, pain, shock. Before testing the tooth in question, it is important to educate and acclimatize the patient to the sensation first on a control tooth. The patient is instructed that they should only respond to a sensation that matches the one elicited from the control tooth (assuming the pulp in this tooth is normal). Asking the patient to respond to any sensation will yield a false positive because if the potential difference is high enough, a sensation could be elicited from the periodontal ligament or adjacent teeth. A more user-friendly method is to ask the patient to hold the lip electrode. The plastic cable is held in one hand and the metal electrode between the forefinger and thumb of the other hand as shown in Figure 4.21c. This method allows the patient to have control by releasing their finger grip on the metal electrode when they feel the defined (not any) sensation; thus reducing the element of an anxiety-driven response. Electric pulp testers should be used with caution on patients who have a cardiac pacemaker; although modern pacemakers are shielded from electrical interference.

Pulp testing of crowned teeth is possible provided a small area of dentine or enamel is available for electrical contact without touching the gingival tissue. A special tip for the Analytic Technology pulp tester (see Fig. 4.21d) is being used on the patient shown in Figure 4.21e. Electric pulp testing cannot discriminate partial pulp necrosis as may happen in the different roots of a molar tooth.

Heat

Dry heat

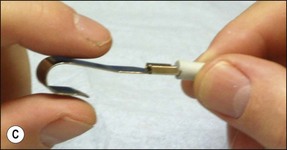

This can be delivered with a commercially available, electrically-heated element, or else crudely, commonly available dental surgery materials may be deployed. The end of a stick of gutta-percha or composition (3 mm) is gently heated in a flame, tested on the gloved hand for warmth and lack of adherence and applied to the suspect tooth. The tooth surface should be lightly coated with petroleum jelly to prevent the composition/gutta-percha from sticking (Fig. 4.22); local anaesthetic should be kept to hand in case of a sharp reaction. Another crude method which has been suggested but is not recommended here, is to generate heat by running a rubber wheel on the tooth using a standard hand-piece (Fig. 4.23).

Hot water

Patients reporting pain due to hot food or drink do not always respond to the above tests. The stimulation requires that the heated medium penetrates particular parts of the mouth and reaches the involved tooth in the same way. This situation can only be replicated using the appropriate medium, normally hot water. Hot water should be sipped and held in the mouth, first over the mandibular quadrant on the affected side and then over the maxillary quadrant if this does not elicit a response. If this fails, an alternative method is to use rubber dam to isolate each tooth in turn and then flood the site with hot water (Fig. 4.24), the temperature of which must simulate the hot beverage eliciting the patient’s pain. If a response is obtained, the suspect tooth is anaesthetized and the heat test repeated.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses