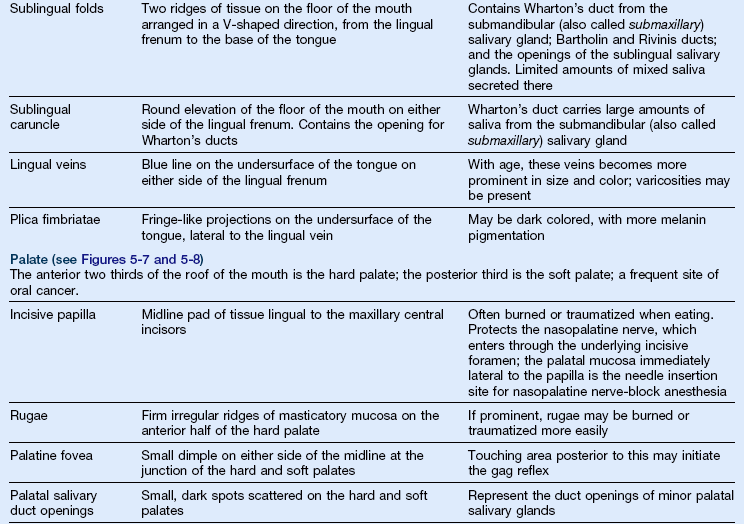

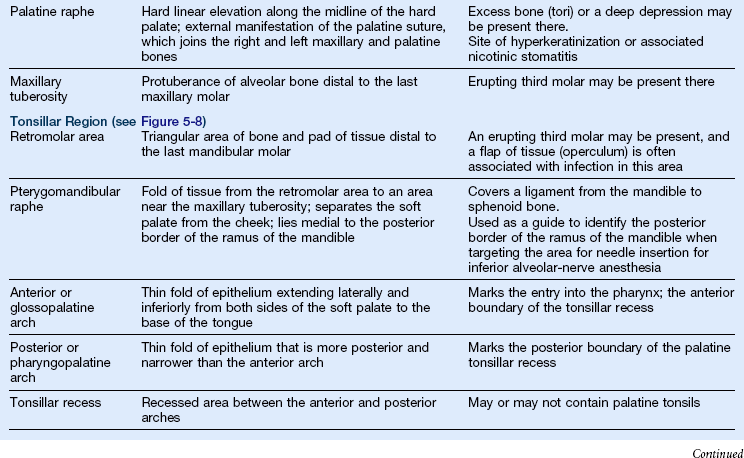

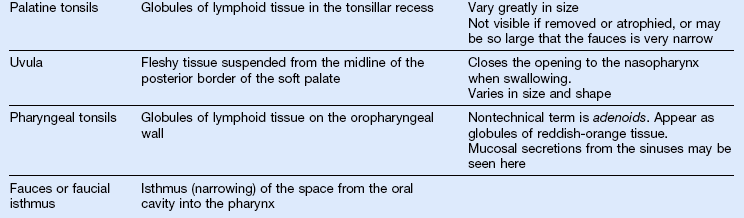

Clinical Oral Structures, Dental Anatomy, and Root Morphology

Clinical Oral Structures

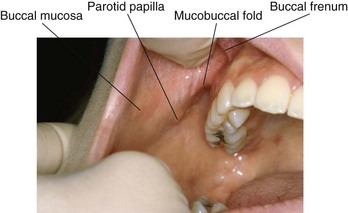

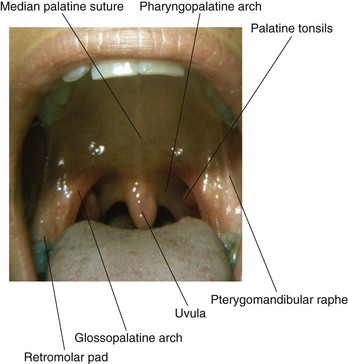

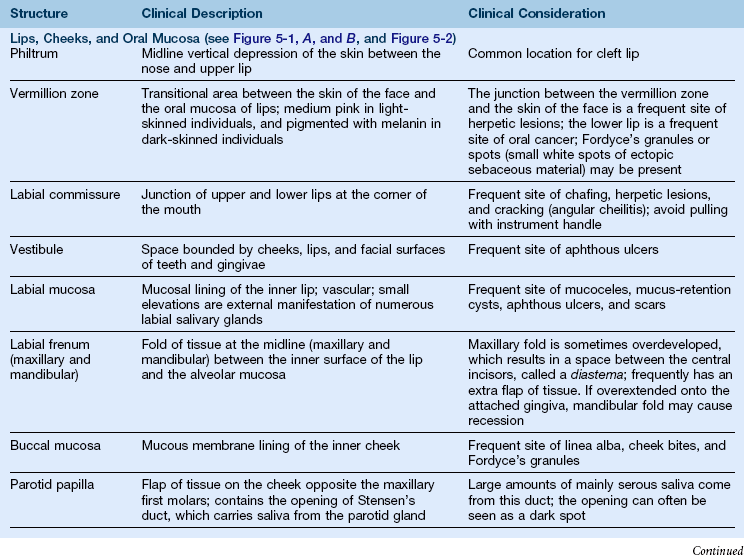

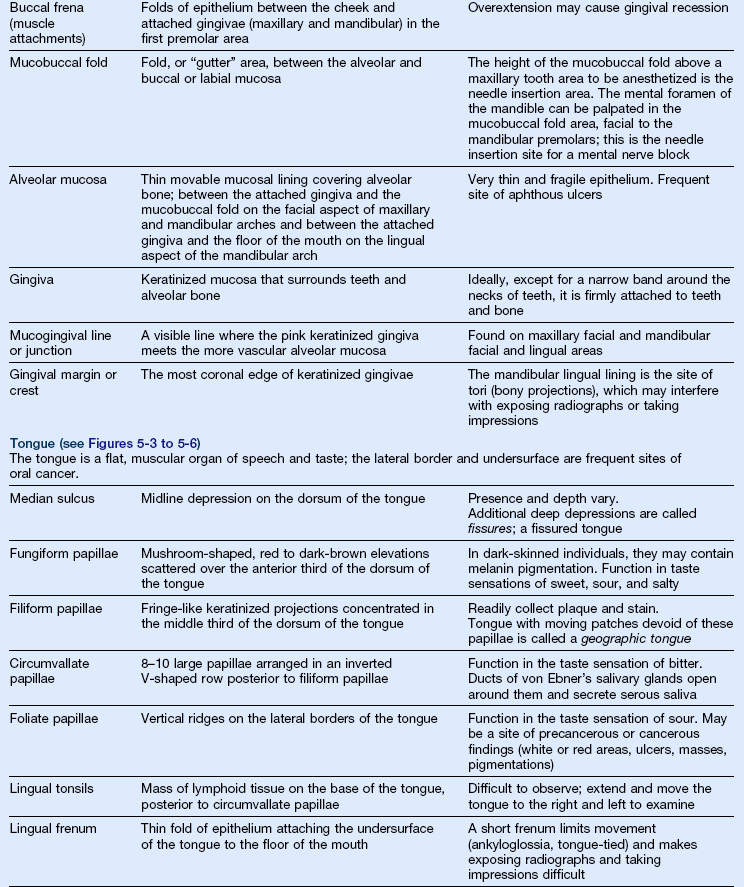

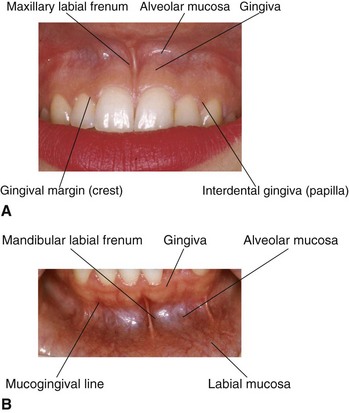

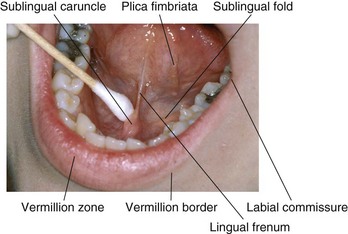

Oral tissues are indicators of a client’s oral and general health. Abnormal conditions can be recognized if the appearance of normal oral structures is known (Figures 5-1 to 5-8 and Table 5-1). Oral structures are identified according to their specific locations and functions. Generally, oral structures appear in shades of pink and may be pigmented in dark-complexioned individuals. In the oral cavity, the presence of melanin pigmentation is random, scattered, and unpredictable.

FIGURE 5-2 Buccal mucosa.

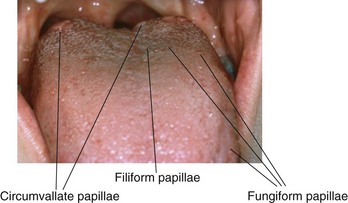

FIGURE 5-3 Dorsum of the tongue.

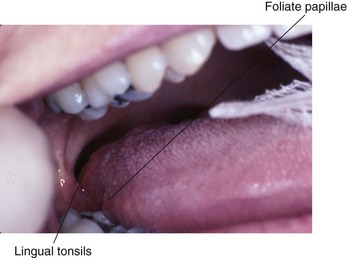

FIGURE 5-4 Lateral surface of the tongue.

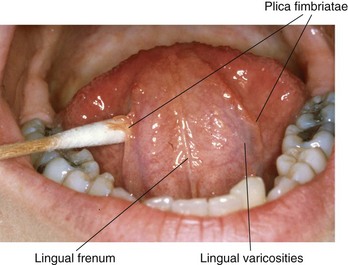

FIGURE 5-5 Ventral surface of the tongue.

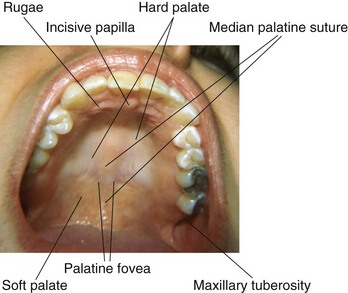

FIGURE 5-7 Hard palate.

FIGURE 5-8 Soft palate and oropharynx.

Dental Terminology

A Parts of a tooth (see the section on “Tissues of the Tooth” in Chapter 2)

2. Root—part of the tooth covered by cementum

a. Apex—rounded end of the root

b. Periapex (periapical)—area around the apex of a tooth

c. Foramen—opening at the apex through which blood vessels and nerves enter

d. Furcation—area of a two-rooted or three-rooted tooth, where the root divides

(1) Furcation entrance—area of opening into the furcation

(2) Roof of the furcation—most coronal area of the furcation; the “ceiling” of a mandibular furcation; the base of a maxillary furcation

(3) Interfurcal area—area between the roots of a two-rooted or three-rooted tooth

e. Root trunk—area from the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) to the furcation

f. Root concavity—broad, shallow, vertical depression on the root; named by location: mesial, distal, and lingual; a concavity located on the furcation side of a root is called a furcal concavity

3. Enamel—hardest calcified tissue covering the dentin in the crown of the tooth; 96% mineralized

4. Cementum—bone-like calcified tissue covering the dentin in the root of the tooth; 50% mineralized

5. Dentin—hard calcified tissue surrounding the pulp and underlying enamel and cementum; makes up the bulk of the tooth; 70% mineralized

6. Pulp—innermost noncalcified tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves

1. CEJ (cervical line)—junction of cementum and enamel

2. Dento-enamel junction (DEJ)—junction of dentin and enamel

3. Cemento-dentin junction (CDJ)—junction of cementum and dentin

1. Facial—surface toward the face

a. Labial (toward the lips)—facial surfaces of anterior teeth

b. Buccal (toward the cheeks)—facial surfaces of posterior teeth

2. Lingual—surface toward the tongue; may also be called palatal for maxillary teeth

3. Proximal—surface toward the adjacent tooth

4. Contact area—area that touches the adjacent tooth in the same arch

5. Incisal—surface of an incisor that is toward the opposite arch; the biting surface; newly erupted permanent incisors have mamelons (projections of enamel) on this surface

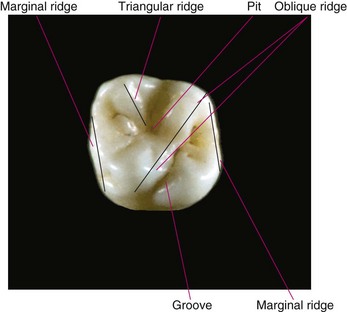

6. Occlusal—surface of a posterior tooth that is toward the opposite arch; the chewing surface; this surface has elevations and depressions; the expression of these anatomic landmarks varies with the population from which they are derived (Figure 5-9)

FIGURE 5-9 Occlusal anatomy.

a. Cusp—large, rounded, elevated area of enamel

b. Ridge—rounded, linear elevation of enamel

(1) Marginal ridge—forms the mesial and distal borders of the lingual surface of anterior teeth and the occlusal surface of posterior teeth

(2) Triangular ridge—ridge from the tip of the cusp to the central developmental groove; formed by the junction of two cuspal inclines

(3) Oblique ridge—collective term referring to two triangular ridges meeting in an oblique line; a characteristic of maxillary molars

(4) Transverse ridge—collective term referring to two triangular ridges meeting in a faciolingual line

(5) Cingulum—large, rounded elevation of enamel on the linguocervical third of anterior teeth

c. Cuspal inclines—two surfaces of a cusp that slant or slope down and away from the crests of the triangular ridge toward developmental grooves

d. Groove—narrow linear depression

(1) Fissure—structural effect of enamel formation manifested as developmental lines or grooves on the external surface of a tooth; the area where the centers of calcification coalesce during tooth development

(2) Developmental groove—groove or line that indicates the primary anatomic divisions (cusps, lobes) of a crown

(3) Supplemental groove—a less distinct groove that branches from a developmental groove

e. Fossa—a shallow, broad depression

f. Pit—a sharp, pointed depression generally located at the junction of developmental grooves (fissures) or at their termination; the opening of a pit may be narrow or wide but is smaller than a toothbrush bristle; pits may be shallow or deep, and their apical descent may be steep or gradual; pits in primary teeth are not as deep as those in permanent teeth

D Junction of surfaces—a tooth has curved surfaces; therefore, no “corner,” where one surface begins and another ends, is present; the transition area is called the line angle area and is named for the surfaces that are involved (e.g., MB, mesiobuccal, DL, distolingual, MO, mesio-occlusal)

E Embrasure—the interproximal space between teeth that begins at the contact area and widens in facial, lingual, occlusal–incisal, and cervical directions; functions as a spillway and escapement area by deflecting food and reducing the forces placed on the periodontium during chewing; also provides a self-cleaning area; the interproximal gingiva fills the cervical embrasure

Dental Anatomy

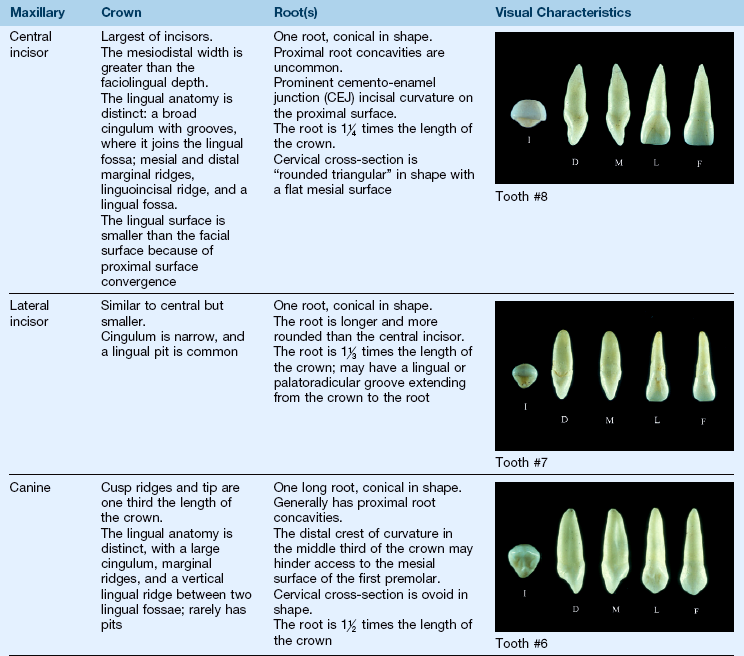

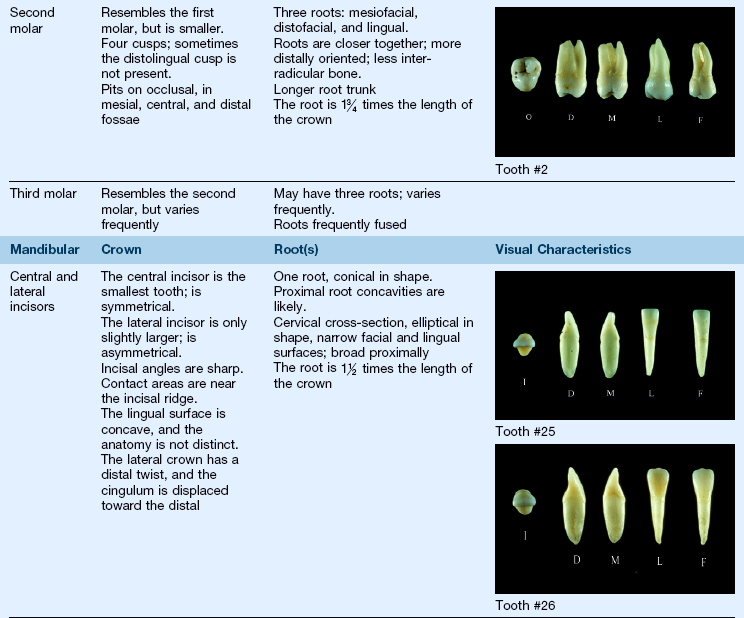

A Permanent dentition (Table 5-2)

1. Humans are diphyodonts, that is, they have two sets of teeth in a lifetime—a primary dentition and a permanent dentition—that span three dentition periods: primary, mixed, and permanent

2. The permanent dentition consists of:

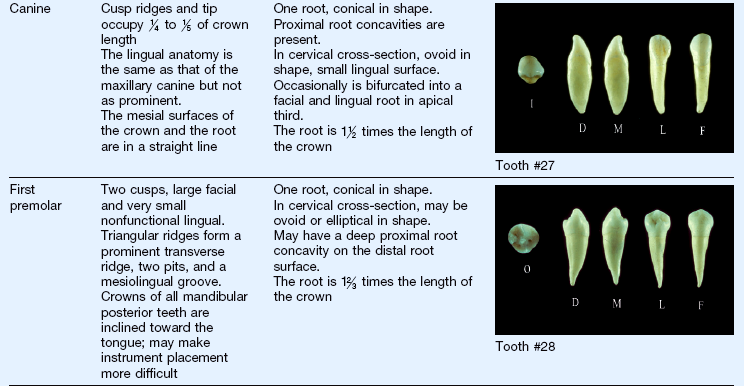

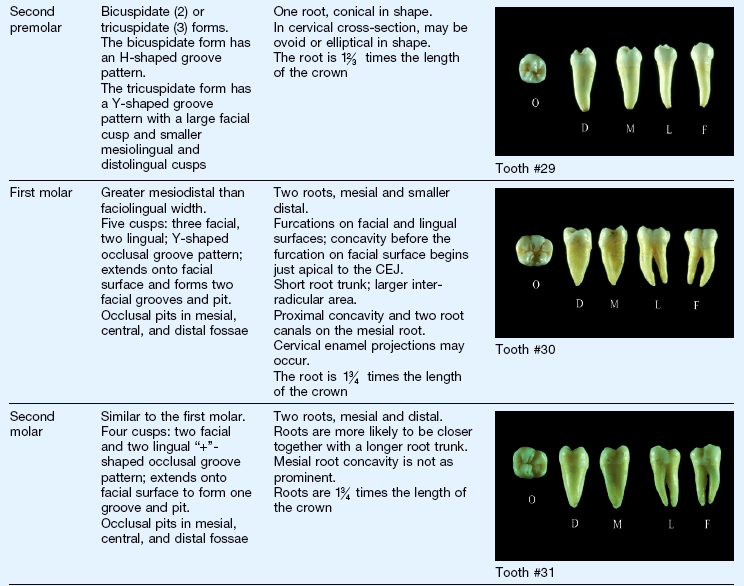

a. Eight incisors, two in each quadrant, named central and lateral incisors, respectively. The four quadrants in a dentition are: maxillary right, maxillary left, mandibular right, and mandibular left

(1) Incisors are the only teeth with an incisal ridge; newly erupted incisors have mamelons—three rounded elevations on the incisal ridge—which are worn away shortly after eruption

(2) Incisal angles—formed by the proximal surfaces and the incisal ridge; central incisor angles are sharper than lateral incisor angles, and mesioincisal angles are sharper than distoincisal angles

(3) Maxillary lateral incisors vary the most in size and shape and may be congenitally missing

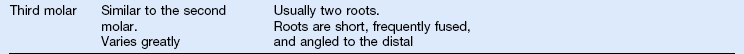

b. Four canines—one in each quadrant

(2) Considered the “cornerstone” of the dentition because of the long, large root, which is externally manifested by the canine eminence of maxillary alveolar bone

(3) Canines and incisors together are considered “anterior” teeth

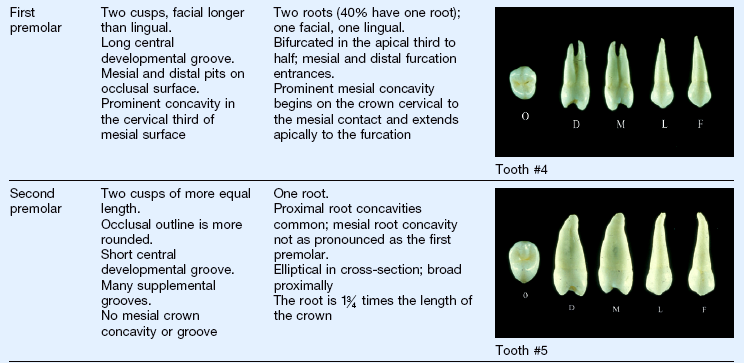

c. Eight premolars, two in each quadrant, named first and second premolars

(1) Generally have two cusps, but the mandibular second premolar also has a three-cusped type, the tricuspidate, which is common

(2) Have one root, except maxillary first premolars, which have two roots 60% of the time

(3) Replace primary molars when they exfoliate

(4) In the past, first premolars were frequently extracted for orthodontic reasons

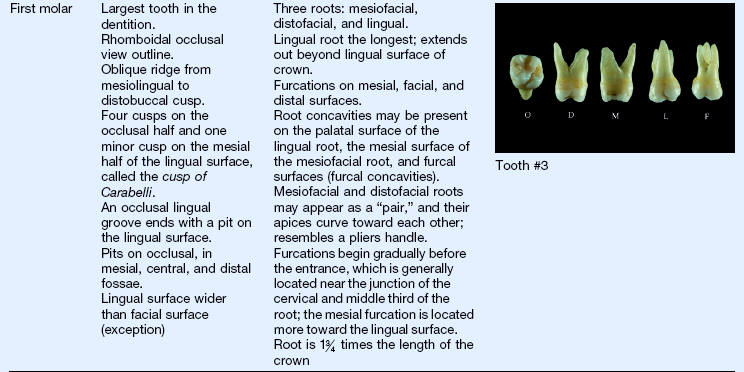

d. Twelve molars, three in each quadrant; named first, second, and third molars

(1) Largest teeth in the dentition

(2) Only teeth that do not replace primary teeth

(3) Erupt distal to the second primary molars; the first mandibular molar is the first permanent tooth to erupt

(4) Multi-cusped, with each having a distinct cusp-and-groove pattern

(5) Maxillary molars have three roots; mandibular molars have two roots

(6) The presence, size, and shape of third molars vary greatly

(7) Premolars and molars together are considered “posterior” teeth

3. The Universal Numbering System (UNS) uses Arabic numerals 1 to 32 to specify permanent teeth, beginning with the maxillary right third molar and ending with the mandibular right third molar; the International Standards Organization (ISO) TC 106 designation system (also referred to as the International Numbering System) uses a two-digit code; the first digit—1 to 4—designates the quadrant in the dentition, clockwise from the upper-right quadrant. The second digit—1 to 8—designates the tooth, from the central incisor to the third molar. For example, tooth 11 is the permanent maxillary right central incisor

4. General characteristics of tooth form

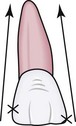

a. All proximal surfaces converge toward the apex from the crests of curvature (height of contour) (Figure 5-10)

(1) This convergence provides spacing for the interproximal gingiva and bone

(2) In an ideal dentition, the proximal crest of curvature is also the contact area, which functions to stabilize adjacent teeth and protect the interproximal gingiva

(3) Proximal crests are located in the incisal or middle third of the crown

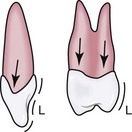

(4) As a general rule, the mesial crest is more incisal–occlusal than the distal crest, and mesial cusp ridges are shorter than distal cusp ridges; mesial outlines are straighter than distal outlines (Figure 5-11)

b. All facial and lingual surfaces converge toward the apex and toward the incisal–occlusal surface from the crests of curvature; this convergence facilitates mastication (Figure 5-12)

c. All facial surfaces of the crown are convex, and the crest of the curvature is located in the cervical third; the lingual surfaces of posterior teeth are convex, and the crest of curvature is located in the middle third; the lingual surfaces of anterior teeth are concave in the middle third; these contours deflect food away from the gingiva and facilitate the function of teeth (Figure 5-13)

d. The CEJ on the proximal surface curves toward the incisal–occlusal surface and is more prominent on anterior teeth than on posterior teeth; the CEJ curves more on the mesial surface than on the distal surface (see Figure 5-13)

e. From a proximal view, the long axes of the crown and the root are in line except for the posterior mandibular teeth, which have the long axis of the crown tilting lingually to the long axis of the root; this lingual inclination enables the intercusping relationship of posterior teeth and the distribution of forces along their long axes (Figure 5-14)

f. Proximal surfaces converge toward the lingual; this is most prominent on maxillary incisors and canines (the two exceptions are the mandibular second premolar and the maxillary first molar) (see Table 5-2 and Figure 5-15)

5. General characteristics of roots

a. Root anatomy is not as complex as crown anatomy, but variations in size, shape, and number frequently occur

b. Teeth have one, two, or three roots

(1) One root—incisors, canines, maxillary second premolars, mandibular premolars

(2) Two roots—maxillary first premolars (buccal and lingual) and mandibular molars (mesial and distal)

(3) Three roots—maxillary molars (mesiobuccal, distobuccal, and lingual)

c. Teeth with two or three roots have a root trunk with depressions that deepen until the trunk divides at the furcation

(1) The more cervical the furcation, the more stable is the tooth because of the divergence of roots with inter-radicular bone

(2) Furcation involvement occurs when a loss of attachment exists apical to the furcation

(3) Furcations that begin close to the CEJ are more likely to become involved in periodontal disease, but access is easier

(4) Furcations are more cervical on the first molars, especially the mandibular first molar

d. Some roots have longitudinal depressions called root concavities

e. Individual roots are basically cone shaped, being widest at the CEJ and converging (tapering) to the apex; more root surface area is present in the cervical than apical third

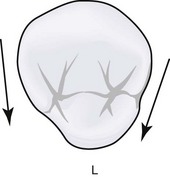

f. A cervical cross-section of a tooth with one root shows three basic shapes (Figure 5-16; see Table 5-2), which may be slightly altered by the presence of root concavities

(1) Triangular—maxillary incisors

(2) Ovoid (egg-shaped)—canines and some mandibular premolars

(3) Elliptical—maxillary premolars, mandibular incisors, and some mandibular premolars

g. Roots that appear triangular or ovoid in cross-section have narrower lingual surfaces

h. A cervical cross-section of molars follows the form of the crown

i. From a facial or lingual view, roots have a distal inclination

j. Second-molar and third-molar roots are more likely to be closer together, fused, and distally inclined

k. The CEJs on posterior teeth have a much less pronounced curvature on all surfaces

6. Clinical considerations of permanent tooth form

a. Clinical considerations of incisor form

(1) Maxillary lingual anatomy is more prominent than mandibular lingual anatomy; however, plaque, calculus, and stain readily collect on mandibular lingual surfaces

(2) The proximal surfaces of maxillary incisors are more accessible from the lingual approach because of the convergence of the proximal surfaces; the proximal surfaces of mandibular incisor roots are difficult to approach because of limited interproximal space and root concavities

(3) As people live longer and keep their teeth, repeated instrumentation on the roots of mandibular incisors places the crowns of these teeth in jeopardy; the very narrow facial and lingual root surfaces are increasingly subject to loss of structure, resulting in unsupported cervical enamel

b. Clinical considerations of canine form

(1) Crown length and bulk make these teeth very stable

(2) The proximal surfaces are more accessible from the lingual approach than from the facial approach because of the convergence of the proximal surfaces

c. Clinical considerations of premolars

(1) Distinctive pit-and-groove patterns facilitate the identification of premolars

(2) Proximal root concavities, especially the mesial of the maxillary first premolar, make subgingival instrumentation difficult on the proximal surfaces

(3) Mandibular premolar crowns, with their small lingual surfaces and lingual inclinations, make instrumentation difficult

d. Clinical considerations of molars

(1) Complex pit-and-groove patterns make molars relatively susceptible to dental caries; they should be sealed shortly after eruption

(2) The lingual inclination of mandibular molar crowns makes the subgingival placement of instruments more difficult on the lingual surface

(3) Proximal furcation areas of maxillary molars should be approached from the lingual aspec/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

inches in length. Anterior crowns are 2 to 3 mm longer than posterior crowns. Roots range between 12 and 17 mm in length; incisor roots are the shortest, and canines are the longest. Proportionally, when comparing the length of roots with their crowns, molars have the “longest” roots overall because of their short crowns; maxillary incisors have the “shortest” roots

inches in length. Anterior crowns are 2 to 3 mm longer than posterior crowns. Roots range between 12 and 17 mm in length; incisor roots are the shortest, and canines are the longest. Proportionally, when comparing the length of roots with their crowns, molars have the “longest” roots overall because of their short crowns; maxillary incisors have the “shortest” roots