Odontogenic cysts and tumours

ODONTOGENIC CYSTS

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The main pathogenic factors include the following:

Epithelial proliferation – either stimulated by inflammation in the case of radicular cysts, or occurring with genetic stimulation in the case of keratocystic odontogenic tumours and probably the glandular odontogenic cysts.

Epithelial proliferation – either stimulated by inflammation in the case of radicular cysts, or occurring with genetic stimulation in the case of keratocystic odontogenic tumours and probably the glandular odontogenic cysts.

Hydrostatic or osmotic factors: may play a part in cyst growth since the cyst wall acts as a semipermeable membrane.

Hydrostatic or osmotic factors: may play a part in cyst growth since the cyst wall acts as a semipermeable membrane.

Keratin formation: may be prominent in keratocystic odontogenic tumours.

Keratin formation: may be prominent in keratocystic odontogenic tumours.

Bone resorbing factors: such as prostaglandins and collagenase.

Bone resorbing factors: such as prostaglandins and collagenase.

Cytokines: IL-1-alpha, TNF-alpha, MCP-1 (Monocyte chemotactic protein-1), and RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (also known as CCL5)), levels are significantly higher in radicular cyst fluids than those in the residual cysts.

Cytokines: IL-1-alpha, TNF-alpha, MCP-1 (Monocyte chemotactic protein-1), and RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (also known as CCL5)), levels are significantly higher in radicular cyst fluids than those in the residual cysts.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Odontogenic cysts are often discovered as an incidental finding on imaging (Fig. 45.1). They are generally symptomless, slow-growing and may reach a large size before they give rise to symptoms, such as:

swelling: cysts in bone initially produce a smooth bony hard lump with normal overlying mucosa but, as the bone thins, it may crackle on palpation rather like an egg shell (termed ‘egg shell cracking’). When the overlying bone is resorbed, the cyst may show through as a bluish fluctuant swelling (Fig. 45.2)

swelling: cysts in bone initially produce a smooth bony hard lump with normal overlying mucosa but, as the bone thins, it may crackle on palpation rather like an egg shell (termed ‘egg shell cracking’). When the overlying bone is resorbed, the cyst may show through as a bluish fluctuant swelling (Fig. 45.2)

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of an odontogenic cyst is based on an adequate history, clinical examination and appropriate investigations, such as pulp vitality testing and radiographs (both intraoral and extraoral) of associated teeth, together with aspiration and analysis of cyst fluids, and histopathology (Table 45.1).

Table 45.1

Aids that might be helpful in diagnosis/prognosis/management in some patients suspected of having odontogenic cyst or tumour*

| In most cases | In some cases |

| Radiography Biopsy |

MRI Aspiration |

TREATMENT (see also Chs 4 and 5)

Odontogenic cysts are managed either by enucleation or by marsupialization (Table 45.2):

Table 45.2

| Regimen | Use in secondary care (severe oral involvement and/or extraoral involvement) |

| Likely to be beneficial | Enucleation Marsupialization |

Enucleation is the complete removal of the cyst: the benefit is that all the cyst tissue is available for histological examination and the cyst cavity will usually heal uneventfully with minimal aftercare. Enucleation is potentially problematic however, if the cyst involves the apices of adjacent vital teeth, as the surgery may deprive the teeth of their blood supply and render them non-vital.

Enucleation is the complete removal of the cyst: the benefit is that all the cyst tissue is available for histological examination and the cyst cavity will usually heal uneventfully with minimal aftercare. Enucleation is potentially problematic however, if the cyst involves the apices of adjacent vital teeth, as the surgery may deprive the teeth of their blood supply and render them non-vital.

Marsupialization is the partial removal of the cyst: the benefit is that it is somewhat less invasive than enucleation and tooth vitality is retained but it requires considerable aftercare and good patient cooperation in keeping the cavity clean whilst it resolves. In order to keep the cavity open, a ‘bung’ or acrylic plug is usually inserted in the opening, often attached to a denture or acrylic splint. The bung stops most food collecting in the cavity, but the cavity must still be syringed by the patient after each meal. Healing is slower than after enucleation: marsupialized cyst cavities may take up to 6 months to close down to the extent of becoming ‘self-cleansing’. The other disadvantage of marsupialization is that not all the cyst lining is available to histopathological examination, and this could lead to misdiagnosis.

Marsupialization is the partial removal of the cyst: the benefit is that it is somewhat less invasive than enucleation and tooth vitality is retained but it requires considerable aftercare and good patient cooperation in keeping the cavity clean whilst it resolves. In order to keep the cavity open, a ‘bung’ or acrylic plug is usually inserted in the opening, often attached to a denture or acrylic splint. The bung stops most food collecting in the cavity, but the cavity must still be syringed by the patient after each meal. Healing is slower than after enucleation: marsupialized cyst cavities may take up to 6 months to close down to the extent of becoming ‘self-cleansing’. The other disadvantage of marsupialization is that not all the cyst lining is available to histopathological examination, and this could lead to misdiagnosis.

INFLAMMATORY CYSTS

Aetiology and pathogenesis

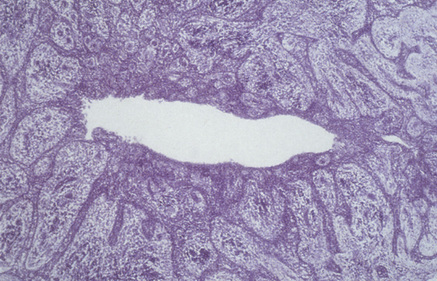

The epithelial lining of inflammatory cysts is derived from the rests of Malassez, which proliferate to produce thick, irregular, often incomplete squamous epithelium, with granulation tissue forming the cyst wall in the denuded areas (Fig. 45.3). Depending on the nature of the inflammatory response, there may be areas of chronic inflammation, or acute inflammation with abscess formation. Cholesterol crystal clefts are often present and mucous cells may be found. The cyst fluid is usually watery, but may be thick and viscid with cholesterol crystal clefts giving it a shimmering appearance. The cysts have capsules of collagenous fibrous connective tissue and cause bone resorption and may become quite large.

Clinical features

Radicular cyst (dental or periapical cyst): where the cyst is associated with the apex of a non-vital tooth. Occasionally, a radicular cyst may develop on the lateral aspect of a root, where the stimulus has been an inflammatory reaction arising from necrotic pulp in a lateral root canal. Radicular cysts are seen especially where:

Radicular cyst (dental or periapical cyst): where the cyst is associated with the apex of a non-vital tooth. Occasionally, a radicular cyst may develop on the lateral aspect of a root, where the stimulus has been an inflammatory reaction arising from necrotic pulp in a lateral root canal. Radicular cysts are seen especially where:

Residual cysts: these arise where an inflammatory cyst (usually a radicular cyst) remains after the removal of the non-vital tooth or root from which it arose.

Residual cysts: these arise where an inflammatory cyst (usually a radicular cyst) remains after the removal of the non-vital tooth or root from which it arose.

KERATOCYSTIC ODONTOGENIC TUMOUR (KCOT: ODONTOGENIC KERATOCYST; OKC; PRIMORDIAL CYST)

The KCOT is the least common, but most dangerous odontogenic cyst. KCOT can be associated with the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS: Gorlin syndrome) (see Ch. 56). By definition, most KCOTs develop instead of a tooth, arising from the dental lamina or remnants, while some, particularly in the posterior mandible, may develop from basal cell off-shoots or hamartomas from the overlying gingival epithelium. They may be associated with the PTCH gene on chromosome 9 and the epithelium may harbour patched (PTCH) mutations, leading to constitutive activity of the embryonic Hedgehog (Hh) signalling pathway.

Diagnosis

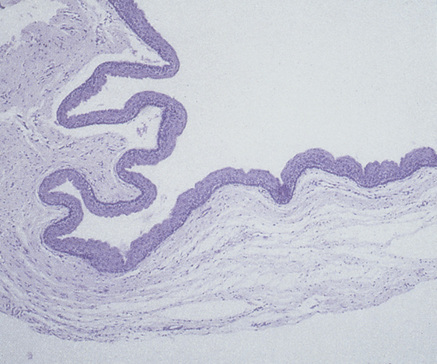

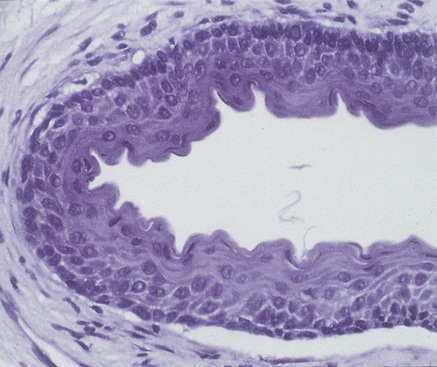

The cyst lining usually has a characteristic appearance of a regular keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, commonly five to eight cell layers thick and without rete pegs (Figs 45.4 and 45.5). There is a well-defined basal layer predominantly of columnar, but occasionally cuboidal, cells. Desquamated keratin is often present within the cyst lumen and the fibrous wall is usually thin.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses