CHAPTER 44

Benign Cysts of the Jaws

Christopher M. Harris1 and Robert M. Laughlin2

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Virginia, USA

2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, California, USA

A cyst is defined as a space-occupying lesion with a connective-tissue outer wall and an inner wall (typically, epithelial tissues) lining. They are typically unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies with sclerotic borders. Cystic lesions of the jaws are divided into odontogenic cysts and non-odontogenic cystic lesions. Cysts typically have the following characteristics:

- Epithelium lining and fluid filled

- Occupy space, and displace or replace normal surrounding tissues

- May resorb or displace adjacent teeth

- May cause expansion of the bone

- May cause neurosensory changes

- Generally do not affect tooth vitality.

Odontogenic cysts arise from the enamel organ. The epithelial sources are the cell rests of Malassez, reduced enamel epithelium, and remnants of the dental lamina. Common non-odontogenic cystic lesions include the traumatic bone cavity, aneurysmal bone cysts, and nasopalatine cysts. All lesions should be treated individually based on their unique histopathology, aggressiveness, and clinical and radiographic presentation. Please refer to Appendix 3 for further treatment guidelines.

Odontogenic Cysts

Periapical Cysts

These cystic lesions arise from a necrotic dental pulp as a result of dental caries or trauma. Histologically, periapical cysts are inflammatory cysts with stratified squamous epithelial linings. Clinically, pulp testing should be completed to verify the presence of a necrotic pulp. Root canal therapy, apical surgery, or extraction of the offending tooth is required for necrotic pulps. Frequently, the authors have encountered cystic lesions associated with a root canal–treated tooth that are not periapical cysts histologically. Determination of tooth vitality is paramount to avoid unnecessary and costly endodontic therapy. Enucleation and curettage, as well as extraction or endodontic therapy of the offending tooth, are required for treatment. Small periapical cysts or granulomas (<1 cm) may resolve without surgical therapy. Recurrence after enucleation and curettage is not expected.

Dentigerous Cysts

Dentigerous cysts are believed to arise from an accumulation of fluid between the crown of an unerupted tooth. The epithelial origin is believed to be the reduced enamel epithelium of the dental follicle. Dentigerous cysts typically occur within the second and third decades of life. Radiographically, these lesions are associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth and are radiolucent. Dentigerous cysts vary in size and produce no calcified structures. Dentigerous cysts are treated by enucleation. Large dentigerous cysts may be treated with marsupialization, especially if wide surgical access is difficult to obtain. Recurrence is rare. Histologic studies of the entire lining are required due to the potential presence of a mural ameloblastoma.

Keratinizing Odontogenic Tumor (Odontogenic Keratocyst)

The odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) has been described by the World Health Organization as a keratinizing odontogenic tumor (KOT). This is primarily due to its aggressive behaviors, which more resemble those of an invasive tumor, and its high recurrence rates compared to a “benign” cyst. OKCs occur over a wide age range, peaking within the second and third decades of life. Histologically, the basement membrane is flattened and corrugated, and has basal palisading of the epithelial cells with parakeratin noted. Within the lumen, large amounts of keratin may be noted. Radiographically, OKCs can present as unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies and can present as small, non-expansile lesions or very large, expansile lesions (Figures 44.1, 44.2, and 44.3). OKCs have recurrence rates approaching 25–30%. Multiple OKCs may be seen in patients with nevoid basal cell syndrome (Gorlin’s syndrome). Treatment for these lesions includes long-term decompression or marsupialization (with or without future enucleation and curettage), enucleation and curettage with adjunctive liquid nitrogen application, aggressive removal of adjacent cyst cavity bone (peripheral ostectomy), application of Carnoy’s solution to the cystic cavity, and/or resection. Resection may be considered for large lesions that perforate the cortex, are difficult to access and visualize, and for recurrent lesions. Inadequate removal of cystic remnants may lead to a recurrence in an area of the maxillofacial region that is difficult or impossible to surgically treat (e.g., the posterior maxilla or ramus–condyle regions). Long-term follow-up is recommended due to the high percentage of recurrence, especially with enucleation and curettage.

Figure 44.1. Orthopantomogram demonstrating a malpositioned tooth #1 and fluid level within the right maxillary sinus.

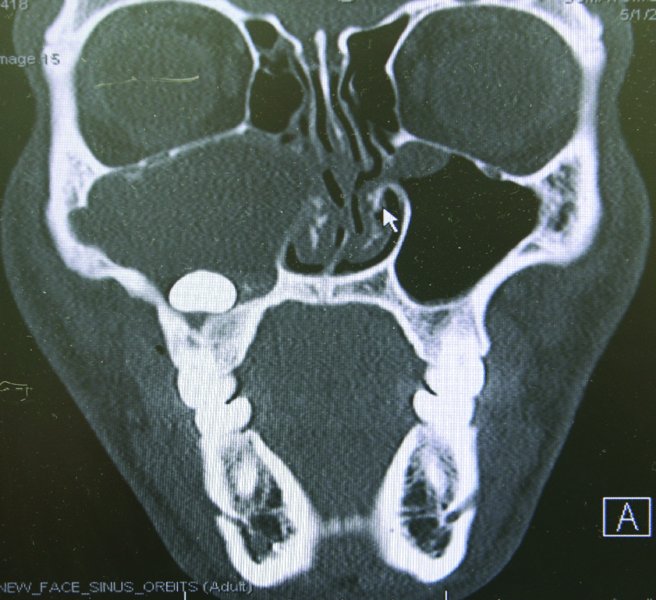

Figure 44.2. Coronal computed tomography scan demonstrating a mass obliterating the/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses