4

What is a Tooth?

Although everyone knows what a tooth is, it is not easy to formulate a precise definition. Referring to human teeth, most people would say:

Teeth are found in all the major groups of backboned animals (vertebrates). In ascending order of complexity, these groups are:

• Fish

• Amphibians (animals that lay their eggs in water)

• Reptiles (animals that lay their eggs on land, as they have hard protective shells)

Birds are excluded because they do not have teeth (but see Chapter 11).

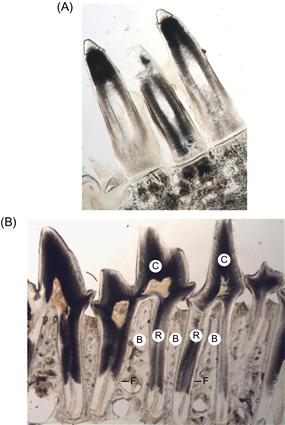

The teeth in fish, amphibians and reptiles differ from those in mammals in four fundamental ways (Figure 4.1):

1. They consist only of crowns that are attached to the surface of the jaw.

3. They are continuously replaced throughout life, so there are far more than just the two sets seen in mammals (see Chapter 9).

Figure 4.1 (A) Section showing three teeth in the conger eel that are attached at their bases to the jawbone and supported without the presence of roots. (B) Section through the jaw of a mammal (loris from Madagascar) showing parts of five teeth, all having a crown (C) in the mouth supported by a root (R) attached to a bony socket (B) in the jaw by a fibrous joint (F).

Source: Courtesy of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons.

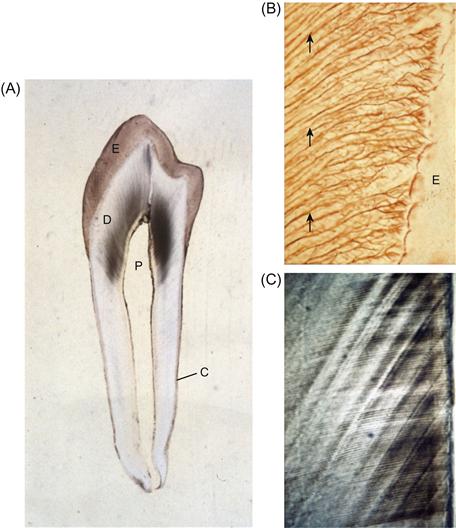

All true teeth have the same structure based on a hard core of dentine that surrounds and protects the central, soft, sensitive, dental pulp. The dentine is covered on the crown by an even harder layer, the enamel. The extra component in mammalian teeth, the root, has a core of dentine covered by a very thin layer of cement (Figure 4.2A), allowing the tooth to be anchored to the surrounding bone by a fibrous joint (Figure 4.1B, label F).

Figure 4.2 (A) Section through a human tooth showing the central pulp cavity (P) (empty due to the method of preparation), protected by dentine (D) forming the body of the tooth. In the crown, the dentine is covered by enamel (E). In the root, the dentine is covered by a thin layer of cement (C), which allows it to be attached to the bone of the socket by a fibrous joint (periodontal ligament). (B) High-power view of the dentine. The arrows indicate the numerous tubules that characterise this tissue. E=overlying enamel. (C) High-power view of the enamel. The complex arrangement of its crystals forms a large number of characteristic lines. The horizontal lines represent enamel rods or prisms, and the oblique lines represent weekly incremental lines (see Chapter 13).

Source: From B.K.B. Berkovitz, G.R. Holland and B.J. Moxham, 2009. Oral Anatomy, Histology and Embryology. 4th edition. Elsevier.

The hardness and resistance to wear of dentine and enamel are related to the presence of mineral crystals of calcium phosphate (and some calcium carbonate). Both enamel and dentine have a complex structure, with dentine being permeated by minute tubes (Figure 4.2B) and the enamel showing many regular lines (due to sudden changes in the orientation of its crystals; Figure 4.2C). Subtle differences in structure may allow an expert to identify an animal from a fragment of its tooth.

Teeth of Invertebrates (Snails, Worms and Leeches)

Although true teeth are only associated with animals that have backbones, some soft-bodied invertebrates have structures that are referred to as ‘teeth’ around their mouth openings. They perform the same task as true teeth, helping the animal gather and break up the food, but the teeth of invertebrates such as snails, worms and leeches do not have any mineralised tissues resembling dentine or enamel.

Snails

Snails possess a structure called a radula with hundreds of tiny ‘teeth’ in the region of the mouth that are used to scrape off their food. The ‘teeth’ are composed of a toughened, horny, organic material and are replaced when worn down. Herbivorous snails use the radula to graze on microscopic plants, whereas in carnivorous species, the teeth are sharper and, together with an acid that is secreted, are used to bore through the shells of their prey.

Worms

While worms may be thought of as harmless creatures feeding on plant remains, bacteria, fungi and algae, there are some species that are serious predators and possess ‘teeth’ composed of hardened organic material.

Polychaetes (poly=many, chaetes=bristles) or bristle worms live mainly in the sea. Some have mouths that they can turn inside-out to reveal jaw-like structures. One of the most remarkable polychaetes is a scale worm that inhabits the recently discovered hydrothermal vents in the very depths of the ocean, where water can reach a temperature of nearly 400°C! At these dark depths, the source of energy at the base of the food chain does not come from plants via the sun (photosynthesis) but from the oxidation by bacteria of inorganic molecules such as hydrogen sulphide (chemosynthesis). The mouth of this scale worm is surrounded by a number of joint-like appendages that have numerous ‘teeth’ to help them grasp and break up the bacteria and small organisms on which the worm feeds (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Mouth parts of a polychaete (scale worm) from a deep ocean hydrothermic vent with tooth-like projections. The mouth is surrounded by a number of sensory antennae.

Source: Courtesy of SPL/Barcroft.

Another polychaete with a fearsome reputation is the bobbit worm. About 2 cm in width, it has been reported to reach a length of 3 m! It burrows in the ocean floor, lying in wait for its prey. Around its mouth, it has up to four pairs of jaw-like claws with ‘teeth’ (Figure 4.4). It strikes with lightening speed and preys on small fish.

Figure 4.4 Mouth parts of the bobbit worm containing tooth-like projections.

Source: ©Ethan Daniels/SeaPics.com.

Leeches

There are many species of leeches, each preying on different hosts. The medicinal leech, widely used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for human blood-letting, is now being reintroduced into hospitals to relieve bruising following plastic surgery. One specialist in Germany places leeches around painful, osteoarthritic knee joints and claims they can provide pain relief lasting for several months.

The leech unusually has three jaws, each surmounted by up to 100 tiny ‘teeth’ (Figures 4.5 and 4.6). Its bite, which is painless, forms a Y-shaped wound (Figure 4.7) through which the leech sucks blood. Leech saliva contains a cocktail of important molecules. One acts as a local anaesthetic, another widens nearby small blood vessels and another (hirudin) acts as an anticoagulant. With these additives, a leech can drink about 10–15 cc of blood before releasing itself, while a further 20–50 cc of blood is lost from the wound prior to a blood clot being formed. The outline of a leech bite made by the three jaws is reminiscent of the Mercedes car logo (compare Figures 4.7 and 4.8).

Figure 4.5 Image showing the three jaws of the leech, each surmounted by many small teeth.

Source: Courtesy of Eye of Science/Science Photo Library.

Figure 4.6 High-power view of the jaws of a leech showing surmounted by teeth (arrows).

Source: Courtesy of Eye of Science/Science Photo Library.

Figure 4.7 Bite from a leech showing a Y-configuration.

Source: Courtesy of Scientifica Visuals Unlimited/Science Photo Library.

Figure 4.8 The Mercedes car logo showing a resemblance to the outline of a leech bite seen in Figure 4.7.

Unlike snails and polychaetes, leech ‘teeth’ have been found to contain mineral salts of calcium, like true teeth, but little is known about their structure.

Teeth of Vertebrates (Fish, Amphibians, Reptiles and Mammals)

Lampreys

The most primitive of the fishes are lampreys and hagfishes. These do not have jaws around their mouths and hence are termed agnathans (a=without, gnathos=jaw). Like sharks and rays, they have a soft skeleton made of cartilage that does not fossilise. The sea lamprey is an eel-like parasite with numerous sharp, hard, hollow teeth. It uses the sucker around its mouth to attach itself to other fish. With its many teeth around the edges of the sucker, it is extremely difficult to dislodge. It rasps away the flesh of the host with its tongue, which also has ‘teeth’ on it (Figure 4.9). There may be up to 120 teeth present. They do not have the structure or mineral content of true teeth, being composed of a tough, horny protein found in other components of the skin, such as claws and fingernails (and also the horn of a rhinoceros). The teeth are continuously rep/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses