Chapter 4

The Role of Mucogingival Therapy

Maximization of treatment results following mucogingival therapy mandates a thorough understanding of the indications, contraindications, and limitations of various therapeutic options, and how best to integrate these options into an individualized, comprehensive treatment plan. Naturally, the need for mucogingival therapy and appropriate definitions of success must first be developed.

The necessity for mucogingival therapy has been a topic of debate in periodontology for a number of decades. Numerous authors have reported upon the ability to maintain periodontal health in the absence of attached keratinized tissues. However, none of these authors has demonstrated periodontal health in the absence of attached keratinized tissues when a restorative margin is present at the gingival crest or intrasulcularly.

A patient presenting with severe gingival recession, a lack of attached keratinized tissue, and an active frenum pull is an obvious candidate for mucogingival therapy to reestablish a stable band of attached keratinized tissue and halt the ongoing disease process (Fig. 4.1). However, it is at least as important to recognize more subtle examples of developing mucogingival problems. A patient who presents with no recession as of yet, a lack of keratinized tissue due to a developmental anomaly which has resulted in mucosa approaching the gingival margin, and a 5–6-mm pocket in the area that is devoid of keratinized tissue, certainly presents with a periodontal milieu that is not conducive to long-term health (Figs. 4.2, 4.3). Whether the soft-tissue margin remains in place and periodontal destruction occurs beneath, or the hard and soft tissues are lost together resulting in a recessive lesion, there is no doubt that such an area will demonstrate continued periodontal breakdown over time.

Fig. 4.1 A patient presents with severe recession, a lack of attached keratinized tissue, and an active frenum pull on the buccal aspect of a mandibular central incisor.

Fig. 4.2 While no active recession is yet noted, the combination of a developmental anomaly characterized by no keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the mandibular central incisor and a 6-mm-deep periodontal pocket in this area has resulted in an unstable periodontal milieu. This combination of an osseous defect and a mucogingival problem will continue to break down if not appropriately treated.

Fig. 4.3 A close-up view demonstrates a lack of attached keratinized tissue and gingival inflammation on the buccal aspect of the mandibular incisor.

It is also important to attain the desired treatment endpoints following mucogingival therapy. Placement of a submarginal soft-tissue autograft, which is separated from residual keratinized tissue by an island of mucosa, does nothing to halt the onset of recession or periodontal disease, until such time as this disease process reaches the submarginal graft that has been placed (Fig. 4.4). Similarly, placement of a “lingerie graft” (Fig. 4.5), which is nothing more than isolated islands of keratinized tissue surrounded by mucosa, serves no functional purpose.

Fig. 4.4 A submarginal gingival autograft has been placed in another patient. Note the mucosa trapped between the preexisting keratinized tissue and the healed graft. This graft offers no assistance in preventing further soft-tissue recession.

Fig. 4.5 The healed “lingerie graft” demonstrates islands of keratinized tissue surrounded by mucosa. Once again, this therapy offers no benefits to the patient.

The added demands placed upon the periodontium by the best fitting restorative margins mandate the establishment of a stable band of attached keratinized tissue to ensure soft-tissue marginal stability. In the most ideal situation, the attachment apparatus proceeding coronally from the alveolar crest will consist of approximately 1 mm of connective-tissue attachment and approximately 1 mm of junctional epithelial adhesion to the root surface, apical to the gingival sulcus. As a result, a minimum of 3 mm of attached keratinized tissue should be provided to ensure soft-tissue margin stability over time. Such a band of attached keratinized tissue will provide coverage over the alveolar crest, thus helping improve long-term periodontal health and stability. Naturally, any habits (i.e., overaggressive brushing) that contributed to the establishment of recessive lesions must first be identified, discussed, and ameliorated. However, performance of mucogingival therapy after significant recession has already occurred around restorative dentistry, while providing a fiber barrier to help protect against further recession, is a less than ideal treatment philosophy (Fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.6 A gingival autograft was placed after significant soft-tissue recession had occurred around the margin of the full-coverage restoration. While this graft will undoubtedly help prevent further recession, timely intervention would have prevented the recession that has occurred.

The three-dimensional adequacy of existing keratinized tissues must also be assessed. A patient presented having been provisionalized for a maxillary full-arch reconstruction. A lack of attached keratinized tissue in an apico-occlusal direction was diagnosed on the buccal aspect of the maxillary cuspid. Note that although adequate keratinized tissue is present apico-occlusally on the buccal aspect of the lateral incisor, this tissue is thin buccolingually (Fig. 4.7). In conjunction with gingivoplasty procedures around other abutment teeth, a gingival autograft was placed on the buccal aspect of the maxillary cuspid (Fig. 4.8). The provisional restoration was recemented (Fig. 4.9). Following healing and final tooth preparations and buildups, the patient is ready to have the final fixed restorations cemented (Fig. 4.10). An adequate band of attached keratinized tissue is present following augmentation on the buccal aspect of the maxillary cuspid. Twenty-four years after therapy has been completed, the patient presents with maintenance of the soft-tissue contours and height on the buccal aspect of the maxillary cuspid. However, recession has occurred on the buccal aspect of the maxillary lateral incisor, where a buccolingual insufficiency of keratinized tissue had previously been noted (Fig. 4.11). Therefore, it is imperative that the adequacy of keratinized tissue be assessed in a three-dimensional manner before deciding upon maintenance or another course of treatment.

Fig. 4.7 A patient presented having been provisionalized for a full arch reconstruction. The maxillary cuspid demonstrated a lack of attached keratinized tissue. Note also that while an adequate band of attached keratinized tissue was present apico-occlusally on the maxillary lateral incisor, the buccolingual dimension of this tissue was inadequate.

Fig. 4.8 A gingival autograft has been placed on the buccal aspect of the cuspid and secured with interrupted silk sutures, in conjunction with gingivoplasty procedures around the other anterior abutment teeth.

Fig. 4.9 The provisional restoration has been recemented.

Fig. 4.10 Following soft-tissue healing and tooth preparations and buildups, the patient is ready for insertion of the final maxillary reconstruction. Note the augmented band of attached keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the cuspid.

Fig. 4.11 Twenty-four years after therapy, the augmented keratinized tissues on the buccal aspect of the cuspid remain stable. However, soft-tissue recession has occurred on the buccal aspect of the lateral incisor, where the buccolingual dimension of the keratinized tissue was inadequate.

The buccopalatal dimension of the keratinized tissue must always be considered. A patient who presents with keratinized tissues that are very thin buccolingually, and almost translucent on the buccal aspects of prominent roots, will be at risk upon introduction of a restorative margin near this thin, highly labile soft tissue. The percentage of soft tissue composed of gingival connective tissue is low in such a situation, as most of the bulk is made up of epithelium and rete pegs. As such, this tissue must be augmented prior to placement of restorative dentistry near the gingival margin, regardless of how thick a band of keratinized tissue is present apico-occlusally.

First popularized by Friedman (1–3), augmentation of deficient bands of attached keratinized tissues was championed as a means to prevent the initiation of soft-tissue recession, halt active recession, and provide a “fiber barrier” to help maintain periodontal health over time. Substitution of delicate, friable mucosal tissues, which are characterized by a loose connective tissue, with their denser keratinized counterparts, was championed as a means of withstanding mechanical and inflammatory insult over time, thus protecting the underlying alveolar bone and improving the long-term periodontal prognoses of the teeth (4–9). While such augmentation usually took the form of a gingival autograft harvested from the palate, a variety of pedicle grafts were designed to help eliminate the need for a second surgical site. A comprehensive review of these techniques has been published (10).

Indications for Mucogingival Surgery

These indications include:

- Active recession (11, 12)

- Root sensitivity

- Patient aesthetic dissatisfaction

- Planned restorative margins at the soft-tissue crest or intrasulcularly (13, 14)

- Anticipated orthodontic movement: While many authors have championed the establishment of thick bands of attached keratinized tissue both apico-occlusally and buccolingually in the direction of planned orthodontic movement (15–17), little or no attention has been paid to the need to ensure the presence of adequate bands of attached keratinized tissues around teeth that will have orthodontic movement in the direction opposite to that of the site in question.

If a patient presents with thin bands of attached tissue apico-occlusally or buccolingually on either the buccal or lingual aspects of the teeth, or demonstrates no keratinized tissues in these areas, it is imperative that augmentation of the keratinized tissues be carried out prior to initiation of orthodontic therapy. The combination of the increased plaque accumulation around orthodontic brackets, wires, etc., and the forces the tooth will be placed under, which result in lesions that mimic occlusal trauma histologically, mandates that adequate bands of attached keratinized tissues be present on all aspects of teeth that will undergo orthodontic movement.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE ONE

A patient presents with a cuspid in the position of the maxillary central incisor. This tooth had previously been restored via a full-coverage approach. There is a lack of attached keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the tooth (Fig. 4.12). The tooth is provisionalized at the desired gingival level (Fig. 4.13). Note the preparation in the root surface, indicative of the extent of the previous restoration. Odontoplasty is performed to smooth the root surface, and a gingival autograft is placed (Fig. 4.14). Ideally, a slight gingivoplasty procedure should have been performed following healing to further enhance the aesthetics of the area. However, the patient refused such therapy.

Fig. 4.12 A patient presents with a full-coverage restoration on a cuspid that has erupted in the position of a maxillary lateral incisor. The patient is aesthetically dissatisfied.

Fig. 4.13 The tooth in the position of the central incisor is provisionalized at the desired final gingival level.

Fig. 4.14 Following odontoplasty to smooth the root surface, placement of a gingival autograft, and tooth restoration following soft-tissue healing, the patient’s aesthetic profile has been greatly improved.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE TWO

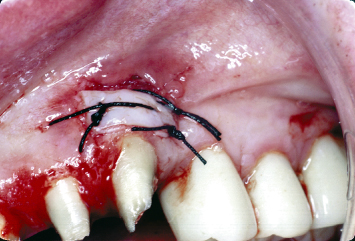

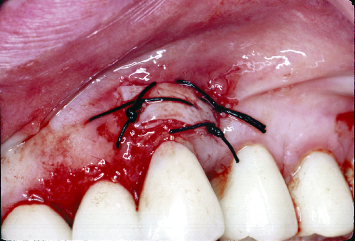

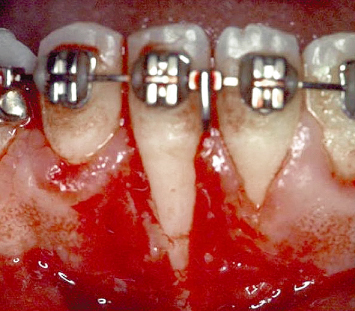

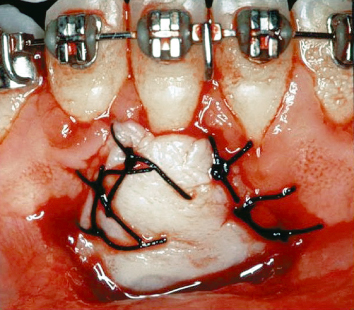

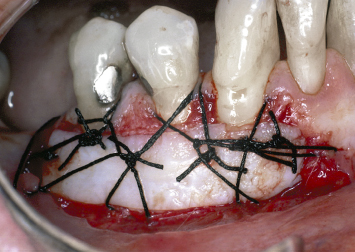

A patient in the midst of orthodontic therapy presents with severe recession on the buccal aspect of a mandibular central incisor. Flap reflection and bed preparation demonstrate significant loss of supporting buccal bone (Fig. 4.15). A gingival autograft is harvested from the palate and secured over the area utilizing interrupted silk sutures (Fig. 4.16). Following healing, a thick band of attached keratinized tissue is present in the area (Fig. 4.17). Note the poor color match and contour of the grafted tissue. Such a nonideal treatment outcome was sometimes encountered when placing gingival autografts in such situations 25 years ago. As will be subsequently discussed, newer techniques are now available, which significantly improve treatment outcomes.

Fig. 4.15 A patient in the midst of orthodontic therapy demonstrates extensive loss of hard tissue on the buccal aspect of the mandibular incisor following bed preparation.

Fig. 4.16 A palatally harvested gingival autograft is placed and secured with interrupted silk sutures.

Fig. 4.17 Following healing, a thick band of keratinized tissue is evident on the buccal aspect of the mandibular incisor. Note the problem with gingival contour and color match that was often inherent in such a procedure when performed 25 years ago.

A lack of attached keratinized tissues in the absence of active recession, root sensitivity, or planned restorative or orthodontic therapy is not an indication for mucogingival surgical therapy.

Nonattached Gingival Autografts

The high level of predictability in providing a stable band of attached keratinized tissues through the use of a palatally harvested gingival autograft is well established. The advantages of such a procedure include the ease of procurement of the needed tissues, and the long-term stability of the transplanted and healed tissues (8, 18).

Traditionally, gingival autografts have usually been placed at a level commensurate with the preexisting soft-tissue margins when utilized prior to the development of recessive lesions, and at the bases of recessive lesions when employed to prevent further recession. While such therapy was predictable, the drawbacks of gingival autograft placement included the need for a second surgical site, significant postoperative morbidity at the donor site, and the compromised “color match” between the grafted tissues and their surrounding host counterparts.

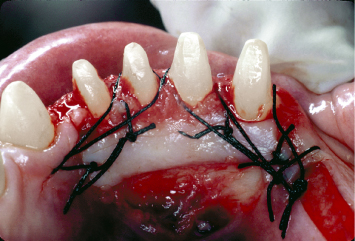

CLINICAL EXAMPLE THREE

A patient presents with significant recessive lesions and a lack of attached keratinized tissues on the buccal aspects of the mandibular cuspid and premolars (Fig. 4.18). The palatally harvested gingival autograft is placed at the level of the preexisting soft-tissue margins, and secured with 4-0 silk sutures (Fig. 4.19). Two weeks postoperatively, the tissues are healing well. It is evident that an adequate band of attached keratinized tissue will be present following tissue maturation (Fig. 4.20).

Fig. 4.18 A patient presents with significant recession and a lack of attached keratinized tissues on the buccal aspects of the mandibular cuspid and premolars.

Fig. 4.19 Following appropriate bed preparation, a palatally harvested gingival autograft is placed and secured with silk sutures. Note the bed extension, which has been carried out to ensure that the graft is not “swallowed up” by the surrounding mucosal tissues.

Fig. 4.20 Two weeks postoperatively, excellent soft-tissue healing is noted.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE FOUR

Following tooth preparation and provisionalization, a lack of attached keratinized tissue is evident on the lingual surfaces of the mandibular anterior teeth (Fig. 4.21). A gingival autograft is harvested from the edentulous area next to the mandibular cuspid and secured on the lingual aspects of the teeth following appropriate bed preparation with 4-0 silk sutures (Fig. 4.22). It is crucial that the recipient bed be adequately extended to avoid disruption of the graft through movement of the tongue and its attachments. This is accomplished with a #15 blade and a Golden-Fox 7 knife. Preparation techniques for the recipient bed prior to placement of a gingival autograft on the buccal aspects of teeth will be subsequently discussed. Following healing, an adequate band of attached keratinized tissue is present on the lingual aspects of the mandibular anterior teeth (Fig. 4.23).

Fig. 4.21 A patient presents with inadequate keratinized tissue on the lingual aspects of the mandibular incisors, which have been provisionalized for full-coverage restorations.

Fig. 4.22 A gingival autograft is harvested from the tissues adjacent to the mandibular anterior teeth and secured with 4-0 silk sutures, following appropriate bed preparation. Such bed preparation is imperative to avoid graft dislodgement due to movement of the tongue and its attachments.

Fig. 4.23 Following healing, a significantly augmented band of attached keratinized tissue is evident on the lingual aspects of the mandibular anterior teeth.

The introduction of surgical modifications and refinements afforded the opportunity to effectively cover previously exposed root surfaces with detached gingival autografts. However, such root coverage does not predictably result in reestablishment of true connective-tissue attachment between the augmented soft tissues and the previously exposed root surfaces. The ability of periodontal ligament cells to migrate over previously exposed root surfaces following gingival autograft placement, in competition with down growth of epithelial cells, has been shown to be approximately 1 mm in all directions. Healing following gingival autograft placement over significant dehiscence defects will therefore result in an area devoid of true connective-tissue attachment of the covering graft to the root surface. The net result is either unattached connective-tissue fibers running parallel to the root surface, or the presence of a junctional epithelial adhesion between the graft and the previously exposed root surface. Either histological outcome is more susceptible to periodontal breakdown and repocketing in the face of inflammation than connective-tissue attachment into root cementum (Fig. 4.24).

Fig. 4.24 Extensive root coverage had been accomplished through placement of a gingival autograft 6 years ago. Unfortunately, the unattached soft tissues covering the root have repocketed and demonstrate significant periodontal inflammation.

As a result, the utilization of gingival autografts to effect root coverage represents a potential compromise, especially in areas that present challenges to appropriate home-care efforts, or where restorative margins are to be placed at the newly established soft-tissue margins or intrasulcularly. A variety of surface preparations has been employed in an effort to attain fiber insertion and reestablishment of connective-tissue attachment between the gingival autograft and previously exposed root surfaces (19, 20–23). Neither citric acid nor other such materials, used alone or in conjunction with hand or rotary instrumentation, has demonstrated predictable establishment of such new attachment.

Recent histologic data have demonstrated the ability to help effect connective-tissue attachment through root-coverage procedures by first treating root surfaces appropriately with PrefGel (EDTA) and Emdogain (porcine enamel matrix protein). Prior to graft placement, the exposed root surface is rinsed with sterile water or saline and air dried. PrefGel is applied for 60 seconds. The surface is once more rinsed with sterile water or saline and air dried. Emdogain is applied to the root surface. The soft-tissue graft is then placed over the root surface.

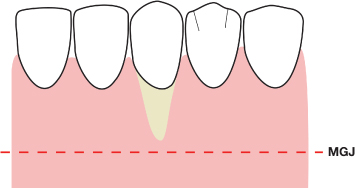

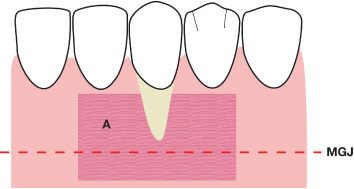

INCISION DESIGNS I

A split-thickness bed is made in the soft tissues apical to the recession around the tooth to be augmented, as well as into the interproximal areas of the adjacent teeth. This bed is made by first extending two vertical releasing incisions at the most distant points of the adjacent interproximal areas from the tooth to undergo soft-tissue augmentation. These vertical incisions are connected at their most coronal extent at the mucogingival junction. In the case of a recessive lesion, they are connected at the level of the mucogingival junction in the interproximal area. This tissue is now reflected and removed in a split-thickness manner to the most apical extent of the releasing incisions. A 15 blade is utilized to bevel all remaining keratinized tissue coronal to the horizontal incision that has been made at the mucogingival junction. Such beveling offers a number of advantages. Beveling of these soft tissues provides a bleeding connective-tissue surface upon which the gingival graft can be overlaid, thus increasing its initial blood supply. In addition, the aforementioned beveling ensures that, following epithelium migration over the grafted tissue onto the host tissues, a smooth confluence of tissues will result, helping to mask the initial incision line. Prior to graft placement, the most apical extent of the bed is extended in a split-thickness manner, utilizing a Golden-Fox 7 knife. This bed is extended laterally 3–4 mm at each of its apical corners. Such extension is important to ensure that the apical borders of the graft are not swallowed up by the vestibular soft tissues during healing (Figs. 4.25–4.28).

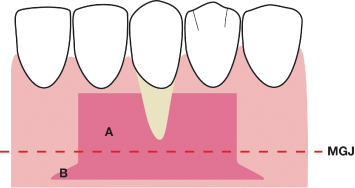

Fig. 4.25 A diagrammatic preoperative view of a mandibular anterior tooth presenting with significant recession. MGJ = mucogingival junction.

Fig. 4.26 A split-thickness mucoperiosteal bed is created, which extends one tooth mesial and distal to the recessive lesion. A = the prepared mucoperiosteal bed; MGJ = mucogingival junction.

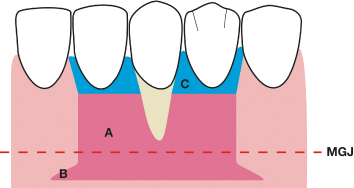

Fig. 4.27 The apical extent of the mucoperiosteal bed is extended mesially and distally with horizontal releasing incisions and further partial thickness reflection, utilizing a Gowen-Fox 7 knife. A = the prepared mucoperiosteal bed; B = the horizontal extensions of the prepared bed; MGJ = mucogingival junction.

Fig. 4.28 The interproximal soft tissues coronal to the prepared bed are beveled in a split-thickness manner, removing the overlying epithelium. A = the prepared mucoperiosteal bed; B = the horizontal extensions of the prepared bed; C = the beveled tissues coronal to the prepared bed; MGJ = mucogingival junction.

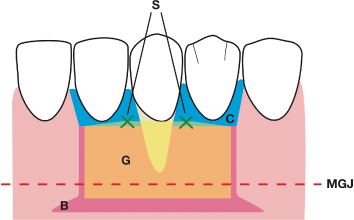

The graft is appropriately contoured and placed over the receptor bed. Interrupted gut sutures are utilized to secure the graft at its most coronal extent in the interproximal areas (Fig. 4.29). No other sutures are placed. The lip is manipulated to ensure that adequate apical bed extension has been carried out, both to avoid displacement of the apical border of the graft and to ensure that the apical border of the graft will not be lost beneath the vestibular mucosa during healing.

Fig. 4.29 The gingival graft is secured with interrupted resorbable sutures in the interproximal area. B = the horizontal extensions of the prepared bed; C = the beveled tissues coronal to the prepared bed; G = the gingival graft; S = the interrupted sutures; MGJ = mucogingival junction.

Lateral Pedicle Flaps

Lateral pedicle flaps have been utilized both to establish bands of keratinized tissue and to cover exposed root surfaces (24–30). The potential advantages of such an approach are the elimination of a second surgical site and a color match superior to that of a detached gingival autograft. A limitation of pedicle flap surgery is the need for an adequate amount of keratinized tissue lateral to the site to be treated for performance of a pedicle flap. Clinicians have previously advocated placing a palatally harvested, detached gingival autograft lateral to the root to be covered, to establish an adequate band of attached keratinized tissue for use in a pedicle graft to effect root coverage. The rationale behind such a procedure is that by rotating a pedicle graft to effect root coverage rather than placing a gingival autograft over a denuded root, the success rate of root coverage is higher due to the maintenance of a blood supply to the pedicle graft. The drawbacks to such an approach include the need to palatally harvest tissue, and the aforementioned problem of color match of the placed gingival autograft with the adjacent tissues.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE FIVE

A patient presents with significant recession and a lack of attached keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the mandibular cuspid. The premolar also requires augmentation of the inadequate band of attached keratinized tissue on its buccal surface (Fig. 4.30). Inadequate keratinized tissue is present distal to the cuspid for rotation as a pedicle graft. A gingival autograft is therefore harvested from the palate (Fig. 4.31). Microfibrillar collagen is placed over the donor site prior to utilization of periodontal dressing, to help control hemostasis (Fig. 4.32). A recipient bed is prepared to accept the gingival autograft on the buccal aspect of the mandibular premolar, as previously described (Fig. 4.33). The gingival graft is secured on the buccal aspect of the premolar utilizing interrupted gut sutures (Fig. 4.34).

Fig. 4.30 A patient presents with significant recession and a lack of attached keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the mandibular cuspid, and inadequate attached keratinized tissue on the buccal aspect of the mandibular premolar.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses