Chapter 4

Sharp safe working in the dental surgery

WHY SHARPS PREVENTION IS IMPORTANT

A sharps injury refers to any injury or puncture to the skin involving a sharp instrument, e.g. dental bur, syringe needle or suture needle. Percutaneous injuries (including human bites) often produce only a minor injury to the skin, but they are clinically significant as they can transmit blood-borne viruses (BBVs), namely hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis B (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). BBV can enter the tissues and cause infection following splashes into the eye, oral mucosa or on broken skin (abrasions, cuts, eczema, etc.); although the risk of transmission by these routes is considerably lower than for sharps injuries. Intact skin forms a barrier to BBV transmission and infection does not occur through inhalation or via the faecal–oral route.

In the dental surgery, the commonest route for transmission of a BBV infection is from an infected patient to a clinician. An infectious dental patient may not necessarily be identified from his or her medical history if he or she is an asymptomatic carrier. Such people are often blissfully unaware of their condition.

Considerably, less often a BBV-infected health care worker will infect a patient, or very rarely transmission occurs from patient to patient via contaminated instruments or environmental surfaces (Redd et al., 2007). Lookback investigations of these outbreaks revealed that transmission tended to occur when the source person was highly contagious due to the magnitude of the viral titre in his or her bloodstream coupled with a breakdown in standard precautions. A dramatic illustration of this type of scenario is an outbreak of hepatitis B centred on an HBe antigen-positive dentist who continued working. He infected 6.9% of the patients attending his practice. Patients were infected only at the times when he omitted to wear gloves during dental treatment (Hadler et al., 1981). Fortunately, occupational acquisition of HBV has declined dramatically over the past two decades because of the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination and increased adherence to standard infection control precautions.

Across the Western Europe, the prevalence of BBV in the general population is low. In the UK, 0.5–1% of the population are seropositive for HCV, approximately 0.6% for HIV and 0.1% for HBV. Although these figures can be up to ten times higher in large inner cities. The implication of these statistics is that most dental practices will have a small number of BBV seropositive patients. Following a single percutaneous injury, especially deep penetrating injuries involving a hollow-bore needle or a device visibly contaminated with blood for the probability of seroconverting is estimated at:

- 1 in 3 for HBV

- 1 in 30–50 for HCV

- 1 in 300 for HIV

- ≤1 in a 1000 for HIV for mucocutaneous (mucous membranes and skin) splashing

An alternative way of looking at these figures is that hepatitis B is 100 times and hepatitis C is 80 times more likely to be transmitted than HIV in the dental setting.

The actual risk of seroconversion is dependent on:

- Prevalence of the infection in the local population

- How infectious is the patient (i.e. high or low viral load in the blood)

- Whether the dental treatment or task is likely to result in a sharps injury

Overall, because of the low prevalence rates of BBV infections in the UK, the risk to dental staff or students of acquiring a BBV occupationally is small.

Health Protection Agency, England, conducted a survey of BBV seroconversion rates in health service staff following occupational sharps injuries from 1997 to 2005. During the 8 years of the survey, only five proven cases of occupationally acquired HIV infection (rate 0.48%) were identified (Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections, 2006). During the same period, 11 (rate 1.8%) health care personnel seroconverted to HCV, one of whom was a dentist. Doctors and dentists suffered from a disproportionately higher number of the percutaneous injuries in comparison to nurses (Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections, 2006). Worryingly, nearly 50% of the incidents were preventable. So, you cannot afford to be complacent in the way you work because of the serious and sometimes life-threatening consequences of a BBV infection (see Chapter 3). As a matter of routine, you should regard blood and blood-tainted body fluids, e.g. saliva as potentially infectious. Protect yourself and prevent onward transmission to others by applying standard precautions, wearing personnel protective equipment (PPE) and practising sharp safe working. The methods of preventing mucocutaneous exposures are discussed in Chapter 5.

WHEN DO SHARPS INJURIES OCCUR

Surveys evaluating sharps injuries affecting American and Scottish dental practitioners found that on an average they sustained 1.7–3.5 sharps injuries per year. We know that many staff are reluctant to report sharps injuries, so these figures may be an underestimate of the true number of incidents. In the Scottish study, 30% of the dentist’s injuries constituted a significant exposure (i.e. source patient, HIV, HBV, HCV seropositive). A small proportion of documented injuries involve the use of increased force, bending needles or passing of sharp instruments between the dentist and the nurse. Whereas most intraoral needlestick and sharps injuries occur accidentally during the course of routine treatment as a result of sudden unexpected patient movements, closing the mouth, or as a consequence of poor visibility, such incidents are intrinsic to working in confines of the mouth. While they can be reduced to a degree by training, behavioural changes and engineering innovations, they cannot be completely eliminated.

PREVENTABLE SHARPS INJURIES

Most sharps injuries happen outside the mouth, during resheathing, dismantling or disposal of needles. Such needle-stick injuries are considered ‘avoidable’ with safe practice. Preventive measures, e.g. safety syringes with retractable sheaves, needle guards or single-handed resheathing techniques, will significantly reduce extraoral injuries. ‘Sharpless surgical techniques’ that use electric scalpels, glues and clips are advocated as a safer alternative to sutures and scalpels.

Clearing up instruments at the end of treatment and manual cleaning are fraught with opportunities for sharps injuries unless precautions are taken. It is during these activities that dental nurses are most at risk. Injuries are usually sustained by the non-dominant hand. Forty per cent of extraoral injuries involve dental burs and probe tips. Fortunately, these instruments are usually less heavily contaminated with blood than hollow-bore needles and so pose less of a risk for transmission of infection. Employers are required to protect their staff from exposure to sharps injuries and BBV under the UK law as specified in the Health Care Act 2006 and COSHH (Control of Substances Hazardous to Health) regulations.

HOW TO AVOID HAVING A SHARPS INJURY

Safe handling of sharps and needles

Injuries associated with handling and disposal of sharps and clinical waste can be minimised by adhering to accepted best practice.

Best practice guide: sharp safe dental treatment

- Use an instrument (mirror/cheek retractor) rather than fingers to retract tongue and cheeks when using sharp implements. This has the added advantage of enhancing visibility

- Do not bend the needle (as this makes resheathing difficult and is more likely to lead to injury) (Figure 4.1)

- If giving multiple injections with the same needle, recap between use

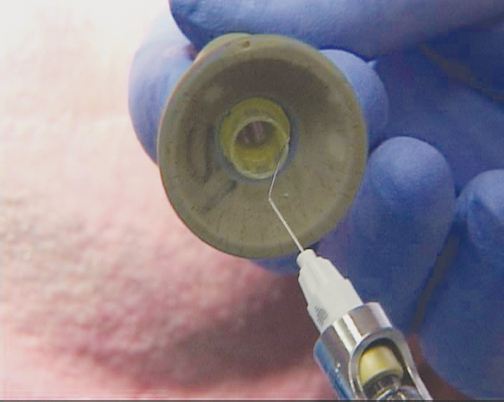

- Recap needles only using a single-handed technique or a needle guard

- Avoid passing sharp instruments from hand to hand during dental treatment

- The same sharp instrument should not be touched by more than one person at the same time. Place the sharp in a neutral zone in the tray or bracket table from where it can safely be picked up by the second person. Alert the other person that you are putting a sharp instrument into the neutral zone.

Figure 4.1 Illustration to show the difficulty in removing a bent needle with safety needle guard.

USE OF SAFETY DEVICES

Safe methods for resheathing syringe needles

Dentistry is unique in its continuing deployment of reusable metal syringes rather than plastic disposable syringes. They are potentially dangerous devices as resheathing and needle disassembly is undertaken at a time when the needle is contaminated with blood. Recent innovations in the design of syringes and other sharps aim to minimise both clinical and ‘downstream’ injuries associated with cleaning and disposing of sharps that affect nurses and cleaners.

- Needle guards and resheathing bloc/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses