Chapter 4

Respiratory disorders

INTRODUCTION

In the United Kingdom, respiratory disorders account for 20% of all deaths; in 2004, 117,000 deaths were caused by respiratory disease compared to 106,000 deaths from ischaemic heart disease (British Thoracic Society, 2006). Mortality rates from respiratory disease have remained static over the last 20 years (British Thoracic Society, 2006). Social class inequality is estimated to be associated with 44% of all deaths from respiratory disease (British Thoracic Society, 2006).

The common occurrence of respiratory disease in the United Kingdom guarantees that it will be encountered in the dental practice. If serious, it can be life threatening. It is essential to assess the patient following the ABCDE approach described in Chapter 3.

The aim of this chapter is to understand the management of respiratory disorders.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ASTHMA ATTACK

There is no standard definition of asthma, though central to all definitions is the presence of key characteristics of the disease, i.e. one or more of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough (British Thoracic Society, 2008).

There is considerable variation between patients in respect of the severity of episodes they experience and the overall course of the disease; for some patients their illness is well controlled and they are asymptomatic between acute attacks while for others the illness can progress to a state of irreversible airway obstruction (Bourke, 2003).

Incidence

It is estimated that in the United Kingdom 5.4 million people have asthma, of whom 1.1 million are children and 4.3 million are adults (Asthma UK, 2013). Although the number of children with asthma has fallen since a peak in the 1990s, the number of adults with asthma is on the increase.

In the United Kingdom, there are approximately 80,000 hospital admissions for asthma each year and 1400 deaths were attributed to asthma (Asthma UK, 2013). Although the incidence of acute asthma episodes in primary care is on the decline (Sunderland and Fleming, 2004), it is nevertheless important to be vigilant. Asthma-related emergencies account for 5% of all medical emergencies encountered in the dental practice (Müller et al., 2008).

Pathogenesis

Asthma is characterised by episodes of reversible airway obstruction where hypersensitivity to certain triggers sets off an inflammatory response during which mucus is released and the muscles of the bronchi constrict (Ward et al, 2010). The inflammatory process involves infiltration of the airway walls by various immune cells, oedema, hypertrophy of mucus glands and damage to the airway epithelial wall (Deacon, 2008). This airway remodelling from persistent inflammation can lead to permanent fibrotic damage.

Causes

Causes of an asthma attack include:

- smoking;

- dust;

- animals;

- stress;

- chest infection.

Source: Ward et al. (2010), Asthma UK (2013)

In the dental practice, stress can trigger an acute asthma attack (Müller et al., 2008).

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of asthma include:

- wheeze;

- shortness of breath;

- chest tightness;

- cough.

Source: British Thoracic Society (2008)

The hallmark of asthma is that these symptoms tend to be:

- variable;

- intermittent;

- worse at night;

- provoked by triggers including stress.

Source: Jevon (2000)

The speed of onset of an acute asthma attack can vary; although there is normally a history of deterioration over a period of days or weeks, an attack can sometimes occur suddenly with rapid deterioration (Rees and Kanabar, 2007).

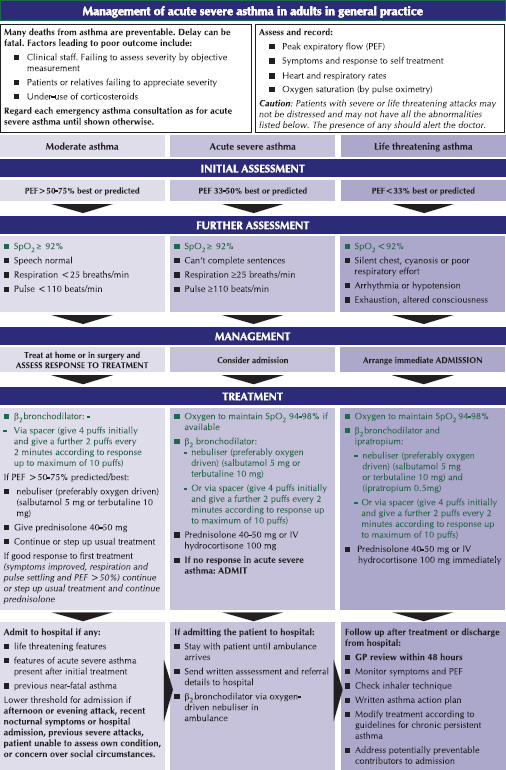

The severity of acute asthma can range from moderate to life threatening (Figure 4.1) (British Thoracic Society, 2008).

Figure 4.1 British Thoracic Society (2008) guidelines on the management of acute asthma (Reproduced with kind permission).

Treatment

The British Thoracic Society has issued guidelines on the management of acute asthma (Figure 4.1).

- Assess the patient following the ABCDE approach described in Chapter 3.

- Sit the patient up (Wyatt et al., 2012).

- If available, consult the patient’s individual action plan in the event of an asthma attack (British Thoracic Society, 2008).

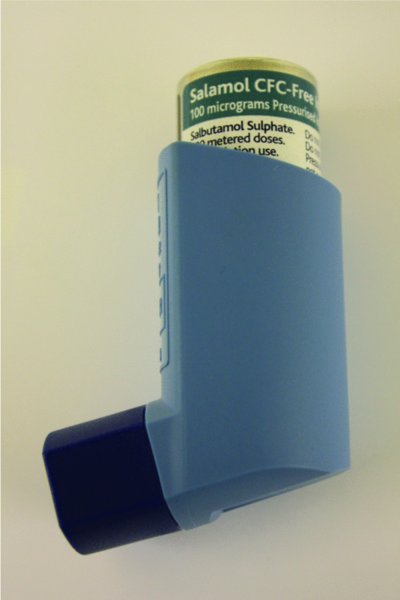

- Encourage the patient to take two puffs of a short-acting beta-2 adrenoceptor stimulant inhaler, e.g. salbutamol (100 μg/puff) (Figure 4.2) (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013). Hopefully the patient will be using his own inhaler and should therefore be familiar with its use and will be administering what his own general practitioner has prescribed. However, if he does not have this with him, use the inhaler stored in the emergency drugs box in the dental practice. (A suggested procedure for using an inhaler is described later.)

- If the patient does not rapidly respond, administer further puffs (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013).

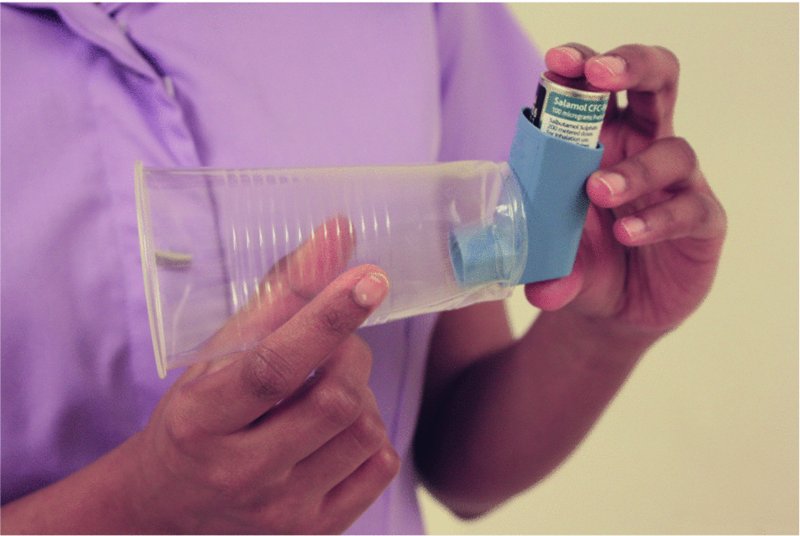

- If the patient is unable to take his inhaler effectively, administer further puffs through a spacer device (Figure 4.3) (see Procedure for using a spacer device); if one is not available, a plastic or paper cup with a hole in the bottom for the inhaler mouthpiece will suffice (Figure 4.4) (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013).

- If the patient does not respond satisfactorily or if deterioration occurs, call 999 for an ambulance; while awaiting transfer to hospital, administer oxygen and also salbutamol 2.5–5 mg via a nebuliser (if this is not available, administer 4–10 puffs of salbutamol 100 μg/puff inhaler preferably via a large volume spacer device, repeating every 20 minutes if necessary (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013).

- Monitor the patient following the ABCDE approach, with particular attention to respiratory rate, heart rate and level of consciousness (British Thoracic Society, 2008; Wyatt et al., 2012) (Boxes 4.1 and 4.2).

- Reassure the patient; an acute asthma attack is frightening and the need to be admitted to hospital can increase anxiety and exacerbate symptoms (Rees and Kanabar, 2007).

Source: Jevon (2000), British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2013), British Thoracic Society (2008)

Figure 4.2 Example of a short-acting beta-2 adrenoceptor stimulant inhaler.

Figure 4.3 Spacer device.

Figure 4.4 Spacer device not available: a plastic or paper cup with a hole in the bottom for the inhaler mouthpiece will suffice (British Medical Association and Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2013).

Indications for hospital admission

Asthma has been classified into moderate, severe and life threatening (British Thoracic Society, 2008) (Figure 4.1). For moderate, severe and life-threatening asthma, the following is recommended:

- Moderate asthma: treat at home or in the surgery and assess response to treatment;

- Severe asthma: immediate transfer to hospital should be arranged if the casualty is not responding to treatment;

- Life-threatening asthma: immediate transfer to hospital should be arranged.

Source: Resuscitation Council (UK) (2012), British Thoracic Society (2008)

Factors lowering the threshold for hospital admission include:

- Afternoon or evening episode;

- Recent nocturnal symptoms;

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses