Red-Blue Lesions

Intravascular Lesions

Congenital Vascular Anomalies

Congenital Hemangiomas and Congenital Vascular Malformations

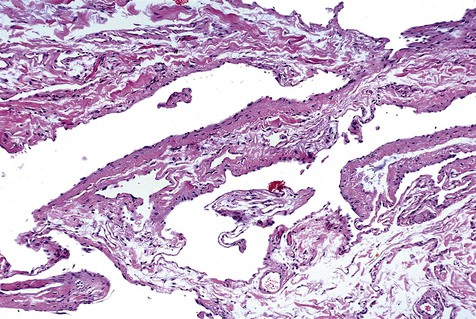

Etiology

The terms congenital, hemangioma, and congenital vascular malformation have been used as generic designations for many vascular proliferations, and they have been used interchangeably. Congenital hemangiomas and congenital vascular malformations appear at or around the time of birth and are more common in females. Because of the confusion surrounding the basic origin of many of these lesions, classification of clinical and microscopic varieties has been difficult. None of the numerous proposed classifications has had uniform acceptance, although there is merit in separating benign neoplasms from vascular malformations because of different clinical and behavioral characteristics (Table 4-1). The term congenital hemangioma is used to identify benign congenital neoplasms of proliferating endothelial cells. Congenital vascular malformations include lesions resulting from abnormal vessel morphogenesis. Separation of vascular lesions into these two groups can be of considerable significance relative to the treatment of patients. Unfortunately, in actual practice, some difficulty may be encountered in classifying lesions in this way because of overlapping clinical and histologic features.

TABLE 4-1

| Hemangioma | Vascular Malformation | |

| Description | Abnormal endothelial cell proliferation | Abnormal blood vessel development |

| Elements | Results in increased number of capillaries | A mix of arteries, veins, and capillaries (includes AV shunt) |

| Growth | Rapid congenital growth | Grows with patient |

| Boundaries | Often circumscribed; rarely affects bone | Poorly circumscribed; may affect bone |

| Thrill and bruit | No associated thrill or bruit | May produce thrill and bruit |

| Involution | Usually undergoes spontaneous involution | Does not involute |

| Resection | Persistent lesions resectable | Difficult to resect; surgical hemorrhage |

| Recurrence | Recurrence uncommon | Recurrence common |

Clinical Features

Congenital hemangioma, also known as strawberry nevus, usually appears around the time of birth but may not be apparent until early childhood (Fig. 4-1). This lesion may exhibit a rapid growth phase that is followed several years later by an involution phase. In contrast, congenital vascular malformations are generally persistent lesions that grow with the individual and do not involute (Figs. 4-2 to 4-6). They may represent arteriovenous shunts and exhibit a bruit or thrill on auscultation. Both types of lesions may range in color from red to blue, depending on the degree of congestion and their depth in tissue. When they are compressed, blanching occurs as blood is pressed peripherally from the central vascular spaces. This simple clinical test (diascopy) can be used to separate these lesions from hemorrhagic lesions in soft tissue (ecchymoses), where the blood is extravascular and cannot be displaced by pressure. Congenital hemangiomas and congenital vascular malformations may be flat, nodular, or bosselated. Other clinical signs include the presence of a bruit or thrill, features associated predominantly with congenital vascular malformations. Lesions are most commonly found on the lips, tongue, and buccal mucosa. Lesions that affect bone are probably congenital vascular malformations rather than congenital hemangiomas.

Encephalotrigeminal Angiomatosis (Sturge-Weber Syndrome)

Encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, or Sturge-Weber syndrome, is a neurocutaneous syndrome that includes vascular malformations with characteristic distribution. In this syndrome, venous malformations involve the leptomeninges of the cerebral cortex, usually with similar vascular malformations of the face (Fig. 4-7). The associated facial lesion, also known as port-wine stain or nevus flammeus, involves the skin innervated by one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. Port-wine stains may also occur as isolated lesions of the skin without the other stigmata of encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis. The vascular defect of encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis may extend intraorally to involve the buccal mucosa and the gingiva. Ocular lesions may appear.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber Syndrome)

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), or Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome, is a rare condition, affecting 1 in 5000 to 8000 people, that is transmitted in an autosomal-dominant manner. Most cases are caused by mutations in two genes: endoglin on chromosome 9 (HHT type 1) and activin receptor–like kinase 1 (ALK 1) on chromosome 12 (HHT type 2). These genes are members of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway and are implicated in vascular development and repair. HHT features abnormal and fragile vascular dilations of terminal vessels in skin and mucous membranes, as well as arteriovenous malformations of internal organs, particularly lungs, brain, and liver (Fig. 4-8). Telangiectatic vessels in this condition appear clinically as red macules or papules, typically on the face, chest, and oral mucosa. Lesions appear early in life, persist throughout adulthood, and often increase in number with aging.

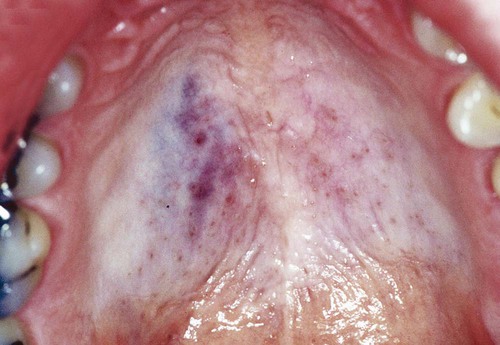

Reactive Lesions

Varix and Other Acquired Vascular Malformations

A venous varix, or varicosity, is a type of acquired vascular malformation that represents focal dilation of a single vein. It is a relatively trivial but common vascular malformation when it appears in the oral mucosa and lips (Figs. 4-9 to 4-11). Varices involving the ventral aspect of the tongue are common developmental abnormalities. Varices are also common on the lower lip in older adults, representing vessel wall weakness caused by chronic sun exposure with subsequent dilation. Varices typically are blue and blanch with compression. Thrombosis, which is insignificant in these lesions, occasionally occurs, giving them a firm texture. No treatment is required for a venous varix unless it is frequently traumatized or is cosmetically objectionable.

Other acquired vascular malformations represent a more complex network or proliferation of thin-walled vessels than simple varices. These are relatively common, are seen in adults, and are of undetermined cause (Fig. 4-12). Some may be related to vessel trauma and subsequent abnormal repair. These lesions present as red-blue discrete and asymptomatic tumescences that can be excised relatively easily.

Pyogenic Granuloma

Etiology

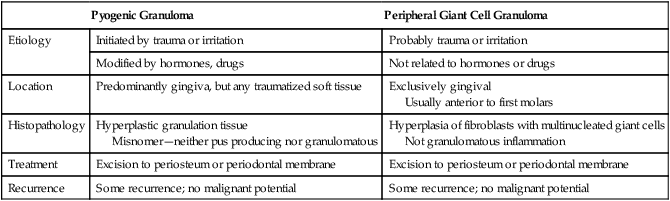

Pyogenic granuloma represents an exuberant connective tissue proliferation to a known stimulus or injury. It appears as a red mass because it is composed predominantly of hyperplastic granulation tissue in which capillaries are very prominent. The term pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer in that it is not pus producing, and it does not represent granulomatous inflammation (Table 4-2).

TABLE 4-2

GINGIVAL REACTIVE HYPERPLASIAS

| Pyogenic Granuloma | Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma | |

| Etiology | Initiated by trauma or irritation | Probably trauma or irritation |

| Modified by hormones, drugs | Not related to hormones or drugs | |

| Location | Predominantly gingiva, but any traumatized soft tissue | Exclusively gingival Usually anterior to first molars |

| Histopathology | Hyperplastic granulation tissue Misnomer—neither pus producing nor granulomatous |

Hyperplasia of fibroblasts with multinucleated giant cells Not granulomatous inflammation |

| Treatment | Excision to periosteum or periodontal membrane | Excision to periosteum or periodontal membrane |

| Recurrence | Some recurrence; no malignant potential | Some recurrence; no malignant potential |

Clinical Features

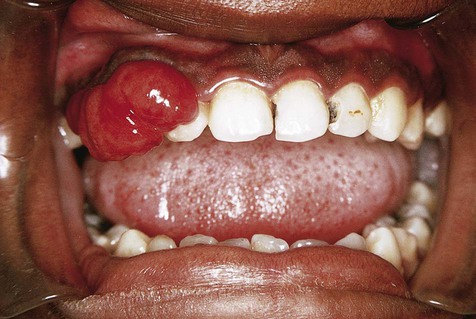

Pyogenic granulomas occur mostly in the second decade of life and are most commonly seen on the attached gingiva (75%), where they presumably are caused by the presence of calculus or foreign material within the gingival crevice (Figs. 4-13 to 4-15). The tongue, lower lip, and buccal mucosa are the next most common sites. Hormonal changes of puberty and pregnancy may modify the gingival reparative response to injury, producing what was once called a pregnancy tumor. Under these circumstances, multiple gingival lesions or generalized gingival hyperplasia may be seen.

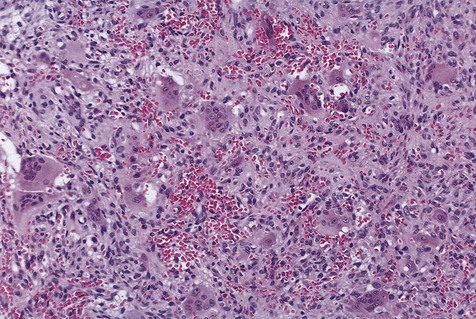

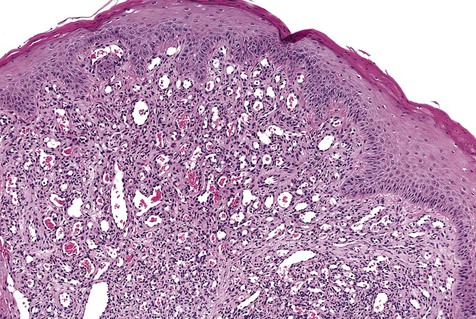

Histopathology

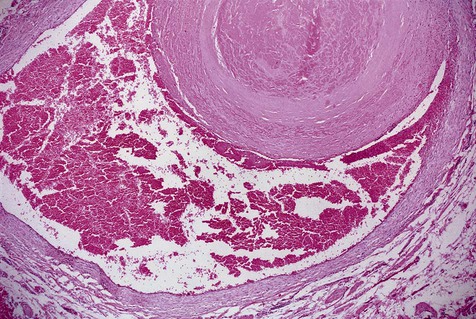

Microscopically, pyogenic granulomas are composed of lobular masses of hyperplastic granulation tissue (Fig. 4-16). Some scarring may be noted in some of these lesions, suggesting that occasionally maturation of the connective tissue repair process may occur. Variable numbers of chronic inflammatory cells may be seen. Neutrophils are present in the superficial zone of ulcerated pyogenic granulomas.

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Clinical Features

Peripheral giant cell granulomas are seen exclusively in gingiva, usually between the first permanent molars and the incisors (Fig. 4-17). They presumably arise from periodontal ligament or periosteum, and they cause, on occasion, resorption of alveolar bone. When this process occurs on the edentulous ridge, a superficial, cup-shaped radiolucency may be seen. Peripheral giant cell granulomas typically appear as red to blue, broad-based masses. Secondary ulceration caused by trauma may result in the formation of a fibrin clot over the ulcer. These lesions, most of which are about 1 cm in diameter, may occur at any age and tend to be seen more commonly in females than in males.

Histopathology

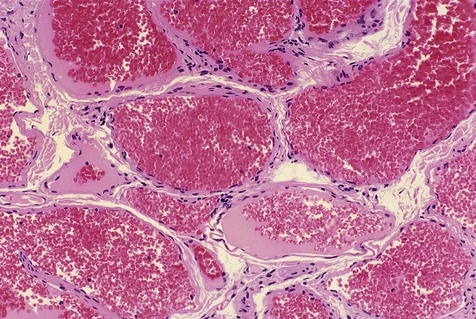

Fibroblasts are the basic element of peripheral giant cell granulomas (Fig. 4-18). Scattered throughout the fibroblasts are abundant multinucleated giant cells believed to be related to osteoclasts. The giant cells appear to be nonfunctional in the usual sense of phagocytosis and bone resorption.

Neoplasms

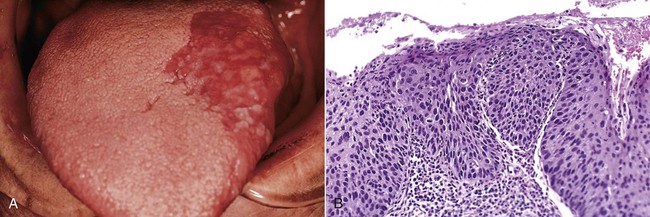

Erythroplakia

Clinical Features

Erythroplakia is seen much less commonly than its white lesion counterpart, leukoplakia. A strong association with tobacco consumption and use of alcohol has been noted. In comparison with leukoplakia, it should, however, be viewed as a more serious lesion because of the significantly higher percentage of malignancies associated with it (Box 4-1). The lesion appears as a velvety red patch with well-defined margins (Figs. 4-19 and 4-20). Common sites of involvement include the floor of the mouth, the tongue, retromolar mucosa, and the soft palate. Individuals between 50 and 70 years of age are usually affected, and no gender predilection is apparent. Focal white areas representing keratosis may be seen in some lesions (erythroleukoplakia). Erythroplakia is usually supple to the touch unless the lesion is invasive, in which case induration may be noted.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses