Chapter 4

Medical Emergencies

- Contents of an emergency drug box

- Staff training

- The ‘ABCDE’ approach to an emergency patient

- Use of defibrillation

- Fainting

- Hyperventilation

- Asthma

- Chest pain of cardiac origin

- Epileptic seizures

- Diabetic emergencies

- Allergies/Hypersensitivity reactions (including anaphylaxis)

- Choking and aspiration

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Stroke

- Local anaesthetic emergencies

It is important that medical emergencies are recognised and the practitioner becomes competent to carry out initial management if they occur. The commonest emergencies seen are faints, hypoglycaemia, asthma, anaphylaxis, angina and seizures.

All members of the clinical team need to be aware of what their role would be in the event of a medical emergency and should be trained appropriately with regular practice sessions. Successful patient management starts with anticipation of the more likely potential medical emergencies that could arise by taking a thorough history.

Contents of an Emergency Drug Box

Medical emergencies may require equipment, drugs or both in order to manage them effectively. If these are not readily available, patients should not be treated. It is also important to check that the drugs are within their expiry date. Remember that different drugs have different ‘shelf lives’.

Drugs to be included as a minimum in the emergency drug box are summarised in Box 4.1. The list is based on that given in the Resuscitation Council (UK) document on Medical Emergencies and Resuscitation in Dentistry, revised in 2008. Clearly, in a hospital environment the availability of emergency drugs is significantly increased. A practitioner registered with the General Dental Council (GDC) should administer only those drugs that they feel competent to handle.

Box 4.1 Contents of an emergency drug box, with routes of administration

| Drug | Route of administration |

| Oxygen | Inhalation |

| Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) spray (400 µg per actuation) | Sublingual |

| Dispersible aspirin (300 mg) | Oral (chewed) |

| Salbutamol aerosol inhaler (100 µg per actuation) | Inhalation |

| Adrenaline injection (1 : 1000, 1 mg/ml) | Intramuscular |

| Glucagon injection (1 mg) | Intramuscular/subcutaneous |

| Oral glucose solution/gel (GlucoGel®)* | Oral |

| Midazolam 10 mg or 5 mg/ml (buccal or intranasal) | Buccal sulcus/inhalation |

* Alternatives:

- 2 teaspoons of sugar/3 sugar lumps

- 200 ml milk

- Lucozade (non-diet) 50 ml

- Coca-Cola (non-diet) 90 ml

If necessary this can be repeated after 10–15 minutes

All drugs should be stored together, ideally in a purpose-designed container.

The optimum route for delivery of emergency drugs is usually the intravenous route, but dentists are often inexperienced in this route of delivery. Formulations have now been developed that allow for other much quicker and more user-friendly routes to be used, and the intravenous route for emergency drugs is no longer recommended as routine for dental practitioners. Oxygen should always be available, deliverable at adequate flow rates (10 l/min).

Staff Training

Staff should be trained in the management of medical emergencies to a degree that is appropriate to their level of clinical responsibility. Skills should be updated on an annual basis.

The ‘ABCDE’ Approach to an Emergency Patient

Medical emergencies can sometimes be prevented by early recognition. An abnormal patient colour, pulse rate or breathing can signal some impending emergencies.

It is important to have a systematic approach to an acutely ill patient and to remain calm. The principles are summarised in the ‘ABCDE’ approach (Box 4.2), but it is useful to start with a brief discussion of some general points. First, ensure that the environment is safe, and note that it is important to call for help at a very early stage. Continuous reappraisal of the patient’s condition should be carried out and their airway (A) must always be the starting point for this. Without appropriate oxygen delivery, all other management steps will be ultimately futile. It is important to assess the success or otherwise of manoeuvres or treatments given, bearing in mind that treatments may take time to work.

Box 4.2 The ABCDE approach to an emergency patient

| A | Airway |

| B | Breathing |

| C | Circulation |

| D | Disability (or neurological status) |

| E | Exposure (in dental practice, to facilitate placement of AED paddles) or appropriately exposing parts to be examined |

If the patient is conscious, ask them how they are. This may give important information about the problem (for example, the patient who cannot speak or tells you that they have chest pain). If the patient is unresponsive, they should be shaken and asked ‘Are you all right?’ If they do not respond at all, have no pulse and show ‘no signs of life’ (breathing (B) and circulation (C)), they have had a cardiac arrest and should be managed as described later. They may respond in a breathless manner and should be asked ‘Are you choking?’

Airway (A)

Airway obstruction is a medical emergency and must be managed quickly. Usually, a simple method of clearing the airway is all that is needed. A head tilt, chin lift or jaw thrust (the latter avoids cervical spine extension) will open the airway. Patients who are unable to speak are to be feared and establishing a patent airway is vital. It is important to remove any visible foreign bodies, blood or debris. The careful use of suction may be beneficial. Clearing the mouth should be done with great care (a ‘finger sweep’ in adults) to avoid pushing material further into the upper airway. Simple airway adjuncts, such as an oropharyngeal airway (Figure 4.1) may be used if the patient is unconscious. An impaired airway may be recognised by some of the signs and symptoms summarised in Box 4.3.

Box 4.3 Signs of airway obstruction

- Inability to complete sentences or speak

- ‘Paradoxical’ movement of chest and abdomen (‘see-saw’ respiration)

- Use of accessory muscles of respiration

- Blue lips and tongue (central cyanosis)

- No breathing sounds (complete airway obstruction)

- Stridor (inspiratory) – obstruction of larynx or above

- Wheeze (expiratory) – obstruction of lower airways, e.g. asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Gurgling – suggests liquid or semi-solid material in the upper airway

- Snoring – the pharynx is partly occluded by the soft palate or tongue

Figure 4.1 An oro-pharyngeal airway.

It is important to administer oxygen at high concentration (10 l/min) via a well-fitting face mask with a port for oxygen. Even patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who retain carbon dioxide should be given a high concentration of oxygen. Such patients may depend on hypoxic drive to stimulate respiration, but in the short term a high concentration of oxygen will do no harm, so its avoidance in the acute situation is unnecessary.

Breathing (B) and Circulation (C)

The clinician should look, listen and feel for signs of respiratory distress. This should be done while keeping the airway open. The clinician should:

- look for chest movement

- listen for breath sounds at the patient’s mouth

- feel for air on the rescuer’s cheek with the rescuer’s head turned against the patient’s mouth.

This should be done for no more than 10 seconds to determine whether there is normal breathing. If there is any doubt as to whether breathing is normal, action should be as if it is not normal, i.e. commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

A patient may be barely breathing or gasping in the first few minutes after cardiac arrest and this should not be mistaken as normal breathing – so-called ‘agonal gasps’. CPR should therefore be carried out if the patient is unconscious (unresponsive) and not breathing normally. Agonal gasps should not delay the start of CPR as they are not normal breathing.

If the Patient Is Breathing Normally

- The patient should be turned into the recovery position (essentially on their side – best learnt as a practical exercise).

- Send for help.

- Ensure that breathing continues.

If the Patient Is Not Breathing Normally

- Ensure help is obtained.

- Start chest compressions:

- kneel at the side of the victim

- place the heel of one hand in the centre of the patient’s chest and the other hand on top of the first hand – it will usually be possible to do this without removing the patient’s clothes. If there is any doubt, outer clothing should be undone/removed

- interlock the fingers of both hands – do not apply pressure over the ribs, upper abdomen or the lower end of the sternum

- the rescuer should be positioned vertically above the patient’s chest. With straight arms, the sternum should be depressed 4–5 cm

- after each compression all the pressure should be released so that the rib cage recoils to its rest position, but the hands should be maintained in contact with the sternum

- the rate should be approximately 100 times per minute (a little less than two compressions per second).

- After 30 compressions, the airway should be opened using head tilt and chin lift and two rescue breaths should be given. This may be carried out using a bag and mask or mouth-to-mouth (with the nostrils closed between thumb and index finger) or mouth-to-mask.

- Practical skills are best learnt on a resuscitation course.

If Rescue Breaths Do Not Make the Chest Rise

- Check for visible obstruction in the mouth and remove if possible.

- Make sure that the head tilt and chin lift are adequate.

- Do not waste time attempting more than two breaths each time before continuing chest compressions.

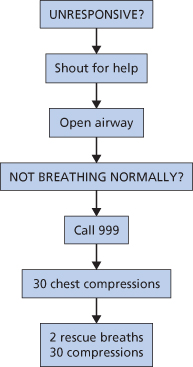

Carrying out these manoeuvres is tiring and if there is more than one rescuer CPR should be alternated between them every 2 minutes. The algorithm for adult basic life support is given in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 The Basic Life Support Algorithm

(reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council (UK)).

Factors to Consider in Assessing Circulation (C)

Assessment of the circulation should never delay the start of CPR. Simple observations to make a gross assessment of circulatory efficiency are given in Box 4.4. By far the most common cause of a collapse that is circulatory in origin is the simple faint (vasovagal syncope). A rapid recovery can be expected in these cases if the patient is laid flat and their legs raised. Prompt management is required, however, as cerebral hypoxia has devastating consequences if prolonged. Other causes than a faint must be considered if recovery does not happen promptly.

Box 4.4 Simple methods of circulatory assessment

Signs

- Are the patient’s hands blue or pink, cool or warm?

- What is the capillary refill time?*

- Pulse rate (carotid or radial artery), rhythm and strength

Symptoms

- Is there a history of chest pain/does the patient report chest pain?

* If pressure is applied to the fingernail to produce blanching, the colour should return in less than 2 seconds in a normal pati/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses