Chapter 4

Gingival Colour Changes – Generalised

Aim

This chapter aims to identify those conditions that may produce widespread colour changes of the gingivae.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the reader should have a working knowledge of the various conditions that can cause generalised red, white and pigmented areas on the gingivae. Additionally there should be an understanding of the differential diagnoses for these respective conditions, together with an appreciation of the nature of the salient clinical investigations required for a definitive diagnosis and subsequent treatment. Table 4-1 summarises the conditions discussed in the text.

| Major Categories | Sub Categories | Frequency of Condition | Management Setting |

| Red lesions | Plaque-associated gingivitis | Very common | Primary care with referral to specialist units if refractory to conventional treatment |

| Desquamative gingivitis | Common. Most frequently due to lichen planus, but vesiculobullous diseases may also cause this condition. | Initial phase of stringent oral hygiene and topical anti-inflammatories can be undertaken in primary care. Recalcitrant or vesiculobullous disease should be referred to specialist units | |

| Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis | Uncommon | Supportive measures and antiviral agents such as aciclovir, which are only of real value if therapy instituted at onset or very early in the course of the disease | |

| Streptococcal gingivostomatitis | Very rare | Difficulty in diagnosis usually means that such cases will be referred for a specialist opinion | |

| Orofacial granulomatosis | Uncommon | Requires specialist management for diagnosis and treatment | |

| Plasma cell gingivitis | Rare | Specialist referral for diagnosis and identification of the allergen (not always possible) | |

| Other gingival hypersensitivity reactions | Uncommon | If the causative allergen can be readily identified and avoided there is no need for referral | |

| Sturge-Weber syndrome | Very rare | Specialist referral required | |

| White lesions | Lichen planus | Common | Recalcitrant lichen planus should be referred to specialist units for diagnostic confirmation, treatment and monitoring |

| Leukoplakia | Although leukoplaki; is not uncommon, it rarely involves large areas of the gingivae | Specialist referral for biopsy (may require multiple samples) and monitoring | |

| Candidosis | Very rare | Referral to specialist units for further investiagtions | |

| Pigmented lesions | Extrinsic staining | Very common | Reassurance in primary care with appropriate advice regarding avoidance of such habits as smoking or betel nut usage. |

| Racial pigmentation | Very common | Reassurance in primary care | |

| Drug-induced/heavy metal pigmentation | Uncommon | Primary care or specialist referral if aetiological agent is not obvious | |

| Addison’s disease | Rare | If this condition is suspected, specialist referral is appropriate |

Red Lesions

The most frequent cause of generalised reddening of the gingivae is that of plaque-associated gingivitis. This topic is extensively covered in various other books in this series and therefore will not be addressed in this chapter.

Desquamative Gingivitis

Desquamative gingivitis is a relatively common clinical presentation, particularly in middle aged to elderly female patients. It is a descriptive term and not a diagnosis in itself. It is therefore important to identify the underlying cause of the condition to ensure appropriate patient management.

Clinical appearance

-

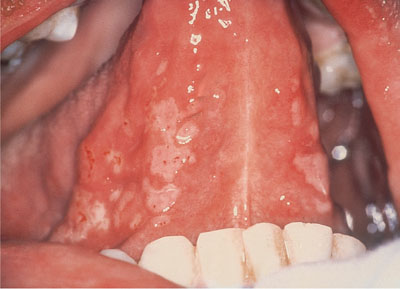

Desquamative gingivitis may range in severity from a mild generalised redness to a florid, fiery red appearance. The gingivae are shiny, smooth and thinned (atrophic), as a consequence of epithelial desquamation (Fig 4-1).

-

In some patients the changes are sporadic rather than confluent affecting only certain gingival sites. It is unclear as to why such localisation occurs.

-

Desquamative gingivitis may involve both the free and attached gingivae.

-

Dependent on its aetiology there may be other features, including lichenoid striae, (Fig 4-2) ulceration or rarely vesicle or bulla formation.

-

Oral hygiene may be poor in the affected areas, leading to exacerbation of the condition due to superimposed plaque-related gingival inflammation.

Fig 4-1 Desquamative gingivitis.

Fig 4-2 Desquamative gingivitis with lichenoid striae.

Clinical symptoms

-

Despite a very florid presentation in some cases, patients can be remarkably free of symptoms.

-

It is not uncommon for patients to complain of some degree of soreness, which is heightened by highly flavoured foods and drinks.

-

Discomfort may cause difficulties in practising effective oral hygiene measures.

Aetiology

The following conditions may produce a desquamative gingivitis:

-

Lichen planus (the most frequent cause – see later).

-

Mucous membrane pemphigoid. (See Chapter 8).

-

Pemphigus vulgaris. (See Chapter 8).

-

Discoid lupus erythematosus.

-

Occasionally linear IgA disease.

-

Hypersensitivity responses to local allergens including certain components of dentifrices. However, on careful clinical examination, such cases of ‘desquamative gingivitis’ have a somewhat granular surface appearance rather than the typical smooth appearance described above.

-

Historically, the hormonal changes associated with the menopause were considered to be an aetiological factor, in view of the predisposition of menopausal females to present with the condition. There is no substantial evidence for this, the association being more a reflection of the typical age of onset of some of the aetiological factors listed above.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

In many cases there may be no other intra-oral or extra-oral involvement. In other cases examination will reveal lesions consistent with one of the aetiological conditions, such as lichenoid striae on the buccal mucosa.

In mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus, desquamative gingivitis may be the first presenting clinical sign, sometimes predating the occurrence of other features by several years. It is therefore important to ascertain if there is any extra-oral involvement (for example ocular in the case of pemphigoid), so that appropriate therapy can be commenced prior to irreversible tissue damage.

Differential diagnosis

-

The aetiological conditions discussed above.

-

Orofacial granulomatosis.

-

Myeloproliferative disease.

-

Linear gingivitis as seen in HIV/AIDS.

Clinical investigation

-

Desquamative gingivitis is diagnosed on clinical features.

-

Biopsy of gingivae may be diagnostically unhelpful as a result of the nonspecific background inflammation masking specific features of the underlying pathology.

-

Biopsy of involved oral mucosa (if present) is often more valuable diagnostically.

-

Indirect and direct immunofluorescence are indicated if there is a suspicion of an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease. Specimens for direct immunofluorescence studies must be unfixed and transferred to the laboratory as soon as possible for appropriate processing. The specimen should be transported in ‘Michel’s medium’ or wrapped carefully in saline-soaked gauze.

Management options

Desquamative gingivitis is often resistant to effective treatment. A high standard of oral hygiene is an essential prerequisite to improving the condition. Appropriate therapy for the aetiological condition should be implemented and topical corticosteroid therapy may be helpful, particularly if administered under occlusion, e.g. fluocinolone acetonide cream delivered via a mouthguard to ensure adequate contact with the affected areas.

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Most cases of primary herpes simplex infection are subclinical and essentially asymptomatic, the patient sometimes having mild non-specific symptoms of malaise and lymphadenopathy. Approximately 10% of cases will manifest as an acute gingivostomatitis with marked systemic malaise.

Clinical appearance

-

Florid, red oedematous gingivae (Fig 4-3).

-

Distribution is not plaque related.

-

Hypersalivation.

-

Vesicles and ulceration of the gingivae, although these are usually present at other oral mucosal sites (Fig 4-4).

Fig 4-3 Inflamed gingivae characteristic of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

Fig 4-4 Erosion of the gingivae in primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

Clinical symptoms

-

Usually occurs in children although young adults are increasingly affected.

-

Acute onset with fever, malaise, sore throat and lymphadenopathy.

-

In young adults the infection can, on occasions, be severe enough to warrant hospital admission and may be confused with Stevens Johnson syndrome.

-

-

Pain from the involved tissues.

Aetiology

-

Primary infection is usually due to herpes simplex type 1 virus but HSV type 2 infection may also be involved.

-

Recurrent or secondary infection produces a herpetic cold sore, although in the immunocompromised, it may manifest in a similar fashion to the primary infection.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

-

Vesicles that rapidly ulcerate appear on the palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, labial mucosa and vermilion border producing characteristic haemorrhagic crusting of the lips (Fig 4-5).

-

The individual ulcers coalesce together forming large serpiginous areas of ulceration covered with a grey/white slough (Fig 4-6).

-

Transmission of the virus to other sites such as the nail beds (herpetic whitlow) (Fig 4-7) and the eye (conjunctivitis; keratitis).

-

Very rarely encephalitis.

Fig 4-5 Labial crusting.

Fig 4-6 Typical ragged serpiginous erosions of Herpes simplex infection.

Fig 4-7 Herpetic whitlow.

Di/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses