4 Dental Anatomy and Occlusion

1.0 INTRODUCTION TO DENTAL ANATOMY

There are tables in this section that provide information on the dimensions and chronologies of the teeth and, in context, referral to frequency variations in eruption sequences, number of roots and root canals, and variations in tooth size and form. It should be recognized that collections of samples that make up these data come largely from Euro-American populations, sometimes limited because of the problem of obtaining data from other populations, access to in utero material, and statistical methods of incorporating diverse data into a common table derived from various sources. For example, prevalence data on a major anatomical variant of the two-rooted mandibular (i.e., one with an additional distolingual and third root) suggest real differences between specific populations as to the prevalence of this variant of the mandibular first molar, which is of special interest for endodontic therapy. Differences in data on tooth eruption and tooth dimensions may not appear to be significant; however, differences in data found in various textbooks and journals need to be addressed. An example of such differences may be seen in the answers to some of the questions. Sexual, racial, and individual variations in dentofacial patterns reinforce the need to carefully consider interceptive extraction or space-regaining therapy for each patient because of the unpredictability of crowding behavior during the transition from mixed to permanent dentition. The effect of racial origin should be considered when using dental sclerosis as a means of age determination in forensic cases.

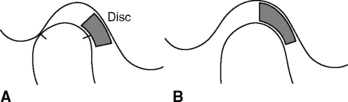

It also must be recognized that changes do occur in terminology; however, they occur in the literature over time, and the reader must be aware of some of the past as well as newer terms that may conceptually relate somewhat differentially to the same aspect of occlusion (e.g., working side contacts [older term] versus laterotrusive contacts [newer term]); therefore, the literature may exhibit several terms that reflect various conceptual views of occlusal relationships. For example, in the Glossary of Dental Terms for the National Board Dental Exam, centric relation is defined conceptually as a position of the mandible with the condyles in a specified location that is independent of tooth contact; however, also included is a synonym for centric relation—retruded contact position. The term retruded has related historically to a concept of centric relation and occlusal contact in which the condyles were thought to be in a most retruded position (Figure 4-1, A) compared to the position of the condyles that is now currently held (Figure 4-1, B).

It is not unusual for dentists to be interested in some of the morphological traits used in anthropological studies (e.g., Carabelli’s trait, peg-shaped incisors, enamel extensions, and shoveling). Because of keyboard limitations, notations in anthropological tables are often limited to di1, di2, dc, dm1, and dm2 for the deciduous dentition, and to I1, I2, C, P1, P2, M1, M2, and M3 for the succedaneous dentition.

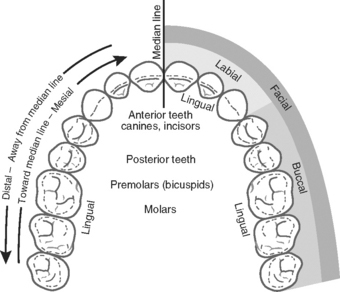

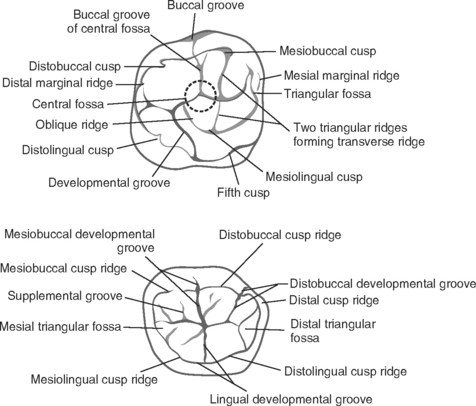

Terms of orientation in dental anatomy generally relate to indicate place, direction, and extent, including such terms as mesial, distal, facial, buccal, lingual, and anterior/posterior as shown in Figure 4-2. Abbreviations related to tooth orientation include: B, buccal; D, distal; DB, distobuccal; M, mesial; MB, mesiobuccal; L, lingual; DL, distolingual; ML, mesiolingual; MM, mesiomarginal; CR, cusp ridge. Abbreviations related to permanent tooth identification in tables include: CI, central incisor; LI, lateral incisor; C, canine; P1, P2, first and second premolars; M1, M2, M3, first, second, and third molars. All the teeth can be identified by one or more numbering systems. The universal system to be considered later is used in this text except where otherwise indicated.

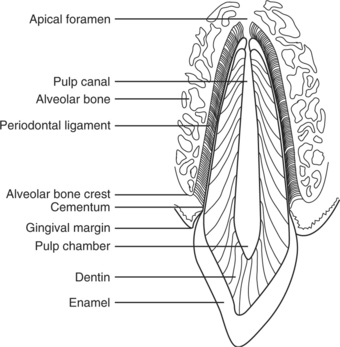

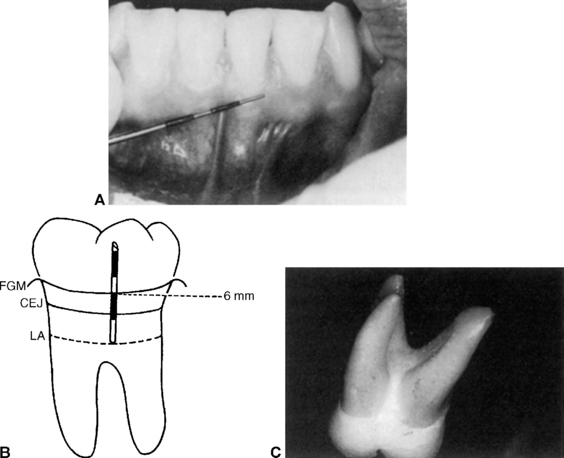

A labiolingual section of a maxillary central incisor (Figure 4-3) shows several of the landmarks relative to the tooth and periodontium.

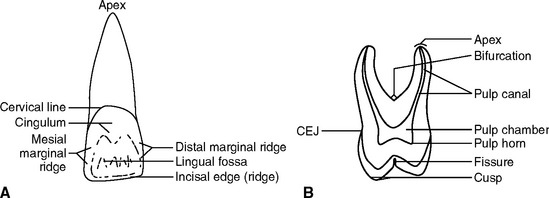

Anatomical landmarks include such terms as crown, root, apex, incisal edge, cervical line, pulp chamber, pulp horn, pulp (root) canal, fissure, cusp, apex, and bifurcation (furcation) as indicated in Figure 4-4, A, B.

The primary and permanent teeth are divided for discussion purposes into the crown and root, which is a division marked on the tooth surface by the cervical line. This line is the junction between the enamel covering the crown of the tooth and the cementum covering the root. It is referred to as the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). It may occur in several forms: (a) the enamel overlapping the cementum; (b) an end-to-end approximating junction; (c) the absence of connecting enamel and cementum so that the dentin is an external part of the surface of the root; and (d) an overlapping of the enamel by the cementum. These different junctions have clinical significance in the presence of disease (e.g., gingivitis, recession of the gingiva with exposure of the CEJ, depth of gingival crevice and level of attachment of the supporting periodontal fibers [Figure 4-3]; cervical sensitivity, caries, and erosion; and placement of margins of dental restorations).

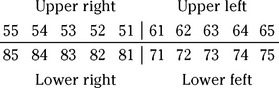

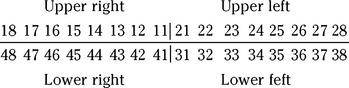

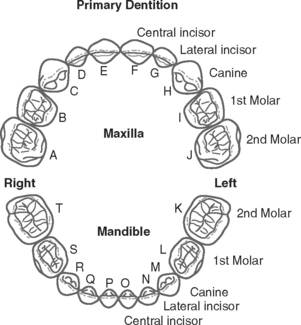

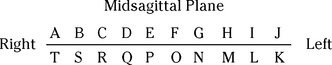

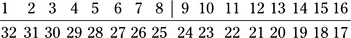

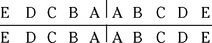

In 1968 the American Dental Association recommended the universal numbering system; however, because it does not have universal usage, there are calls to change it. Even so, the notation of one letter for each tooth in the primary dentition and one number for each tooth in the permanent dentition has made its use favored in the United States. An overview of the primary dentition and its universal numbering is shown in Figure 4-7. A simplified scheme to show the letter notations for the 20 primary teeth in four quadrants follows:

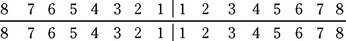

As shown, the right maxillary central incisor is indicated with the letter E. Similarly, the left mandibular left central incisor is indicated with the letter O. There is no provision for supernumerary teeth. An overview of the permanent dentition and its universal numbering is shown in Figure 4-8. A simplified notation scheme for the permanent dentition follows:

The Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI) recommends a two-digit system for both the primary and permanent dentitions. This system has been adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and is accepted by other organizations and in research and public health journals. The FDI system of notation for the primary dentition follows:

2.0 DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN DENTITIONS

The timing of chronological events in the development of the dentitions has been historically difficult to ascertain because of the lack of adequate documentation of the sources of information. Tables of dental chronologies reflect an abbreviated version of a long history of accumulated successive compilations and revisions of chronologies of the primary teeth, which is also true for the permanent dentition. It is recognized that such chronologies have some deficiencies in population sampling and collection methods, and that incorporating revised data based on making critical choices from available sources is not without methodological errors. Recent partial chronologies of dental development reflect the use of statistical methods that provide three different types of formation data: age of attainment chronologies based on tooth emergence, age of prediction chronologies based on being in a stage of development, and maturity assessment scales used to assess whether a subject of known age is ahead of or behind when compared with a reference population. These types of chronologies are used when more precise information about a particular aspect of dental development is needed for research and surgical procedures.

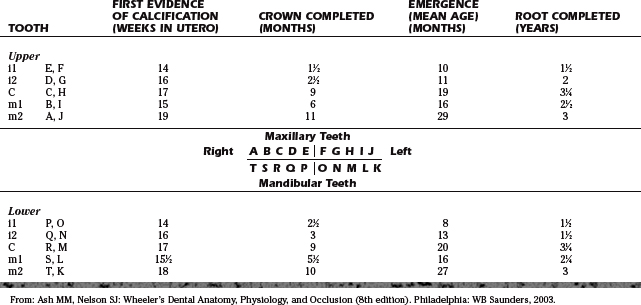

3.0 CHRONOLOGY OF PRIMARY DENTITION

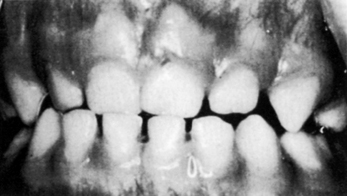

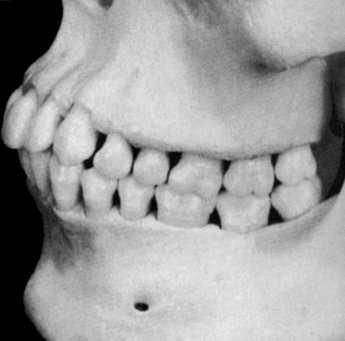

The primary dentition (Figure 4-9) is considered to be clinically complete when the second primary molars are in occlusion at about the mean age of 29 months, keeping in mind that the completion of the roots of the canines occurs at about 3.25 years of age. The emergence of the permanent first molars signals the start of the mixed dentition period, which is considered to have been completed when all the primary teeth are lost and only the succeeding permanent (succedaneous) teeth are present.

Figure 4-9 Primary dentition in a 5-year-old child.

(From Ash MM, Ramjford SP: Occlusion. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995.)

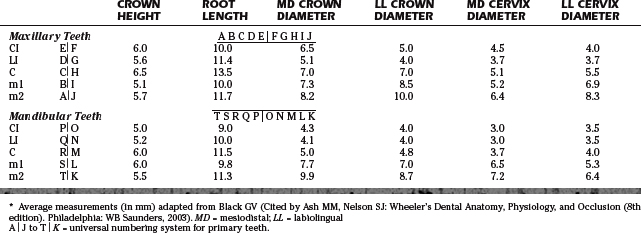

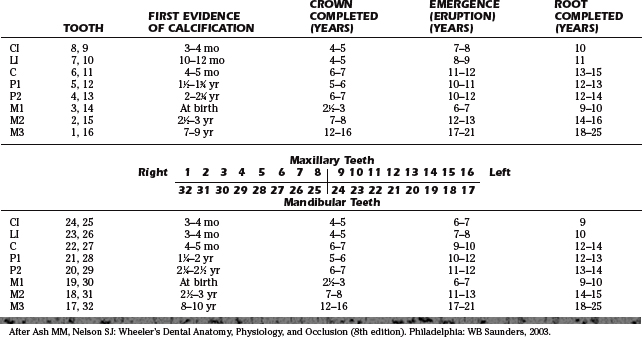

The chronology of the primary dentition is summarized in Table 4-1. The universal numbering system for the primary teeth is used, as well as general indications of primary incisors, canine, and molars i1, i2, C, m1, and m2. The dimensions for the primary dentition are given in Table 4-2.

4.0 MORPHOLOGY OF PRIMARY TEETH

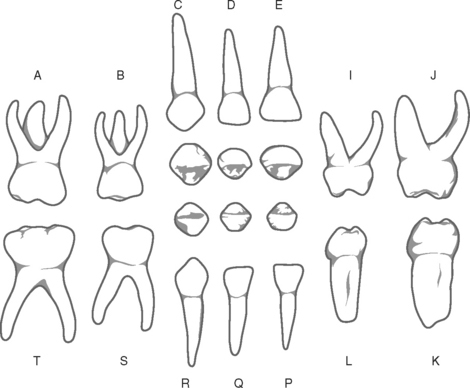

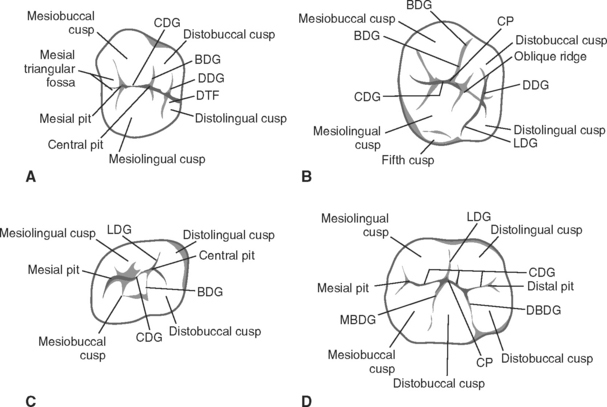

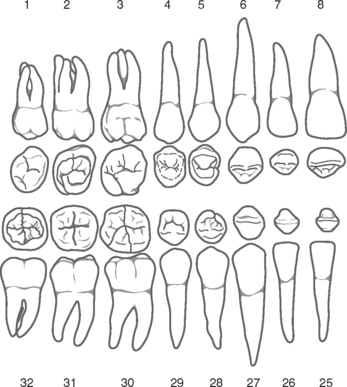

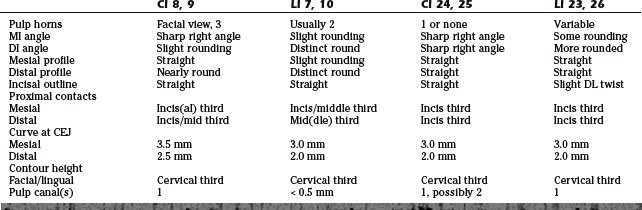

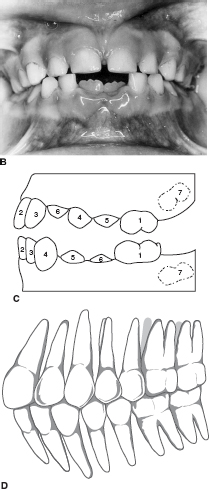

Schematic views of the primary dentition are shown in Figure 4-10. Illustrated are the labial and facial surfaces as well as the occlusal incisal views of the incisors and canines. Occlusal views of first and second primary molars are provided in Figure 4-11.

5.0 CHRONOLOGY OF PERMANENT DENTITION

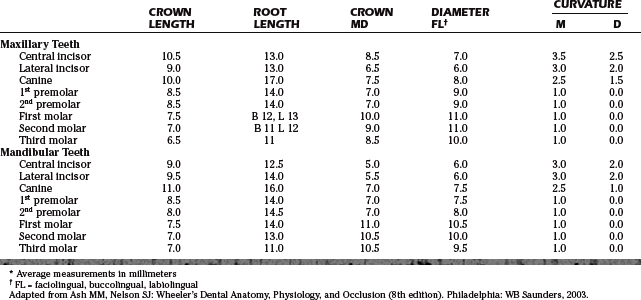

The permanent dentition of 32 teeth is completed by 18 to 25 years of age, as indicated in Table 4-3. Such a table suggests the complexity of bringing together all the biological mechanisms at the right time and place to provide the appropriate relationships between tooth form and jaw movements, tooth form, and supporting structures of the teeth, and the alignment of the teeth and their contact relationships with adjacent teeth and opposing teeth in opposing arches, all in such a way as to stabilize the occlusion and protect the supporting structures of the teeth. The dimensions for the permanent dentition are provided in Table 4-4.

6.0 MORPHOLOGY OF PERMANENT TEETH

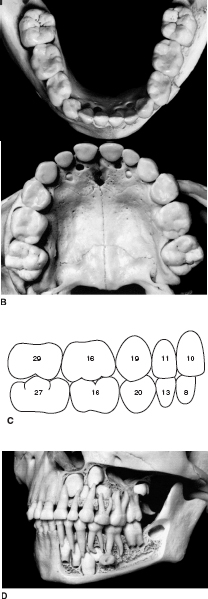

A schematic representation of the permanent dentition is shown in Figure 4-12. The teeth of each side of the arches are indicated with their universal system numbers.

7.0 DEVELOPMENT OF DENTAL OCCLUSIONS

The development of occlusion involves three time frames (i.e., time of emergence and contacting of the primary teeth, period of the mixed dentition with emergence and contacting of permanent teeth, and the time when the rest of the permanent teeth emerge and make occlusal contact). The factors that determine the size of the teeth and dimensions of the jaws and provide room for succedaneous teeth relate to the orderly transition from the primary dentition through the mixed dentition to the permanent dentition and its completion. For example, the chances for crowding in the permanent dentition based on the available spaces between the primary teeth (>6 mm) would be none; however, for 3 to 5 mm of spacing in the primary dentition, the chances of crowding are 1 in 5. If the primary teeth are crowded, there is a 1:1 chance of crowding of the permanent dentition. Among other factors, the availability of interdental spaces in the primary dentition is dependent on tooth size and dimension of the arches. The chance is small for crowding of the permanent dentition in the patient seen in Figure 4-13.

The primary teeth should be in normal alignment and occlusion should occur shortly after the age of 2 years, with all the roots fully formed by the time the child is 3 years old. With the growth of the jaws, the anterior teeth separate, beginning between 4 and 5 years of age. The primary occlusion is also supported and made more efficient by the emergence of the first permanent molars (sometimes referred to as 6-year molars) immediately distal to the primary second molars, as illustrated in the development of occlusion shown in Figure 4-14, A, B. The sequence of eruption (in months) is depicted in Figure 4-14, C. The completion of the primary occlusion and developing permanent dentition is shown in Figure 4-14, D.

The development of the permanent occlusion (Figure 4-15, A) begins with the emergence and contacts of the first permanent molars at about 6 years of age and, except for the third molar, is concluded at about 15 to 18 years of age. The emergence of the mandibular incisors (Figure 4-15, B) follows the 6-year molars at 6 to 7 years of age. The most favorable sequence of eruption/emergence of the permanent dentition for a normal occlusion is shown in Figure 4-15, C. The third molars emerge and come into occlusal contact later, usually by 25 years of age (Figure 4-15, D).

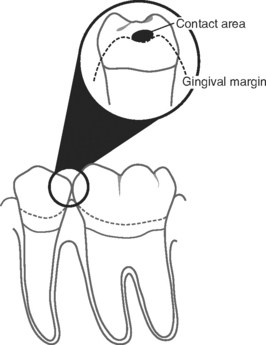

When the teeth are in ideal alignment so that proximal contacts and marginal ridges are in proper position (Figure 4-16), there is less of a chance of impaction of food into the interproximal areas, resulting in loss of periodontal attachment.

Room for the development, eruption, and emergence of the permanent teeth during the mixed dentition period is influenced by the forward rotation of the maxillomandibular complex. An important part in the development of the occlusion of the permanent dentition is the premolar segment where the erupting premolars are significantly smaller in the mesiodistal diameter than the primary molars, which they replace (i.e., the mesiodistal diameters of the mandibular primary molars are greater than the mesiodistal diameter of the replacing premolars). This gain in space between the primary and permanent dentition in the dental arch is referred to as the leeway space. It has importance for the alignment of the mandibular incisors and for mandibular molar movement to correct for the end-to-end molar relationship in the mixed dentition period into a normal molar relationship in the permanent dentition (e.g., mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occluding in the mesiobuccal developmental groove of the mandibular first molar, as shown in Figure 4-17, A, which is an angle class I molar relationship).

There is a general relationship between the size of the teeth and the size of the dental arches; however, when a discrepancy is evident between the aggregate mesiodistal diameters of the crowns of the teeth and the size of the bony supporting arches, crowding or protrusion can occur. Arch width and perimeter dimensions can relate to differences between crowded and uncrowded dentitions.

8.0 OCCLUSAL CONTACT RELATIONS AND MANDIBULAR MOVEMENTS

In the generally accepted definition of normal occlusion, each mandibular tooth is positioned lingual to the maxillary counterpart. It may also be helpful to note that the mandibular teeth are positioned about one half of a tooth anterior to the maxillary counterpart, excluding the central incisors (Figure 4-18). In this position, occlusal contacts may follow two primary forms. (Figure 4-19). It should be noted that the following descriptions relate to so-called idealized contact relations—a concept that can be used as a basis for discussion, as well as for developing occlusal contact relations in restorative dentistry and orthodontics. Individuals may often show variations from the patterns as presented without having occlusal dysfunction.

Again, from Figure 4-19, A, the contact relations occurring with the maxillary lingual cusps (maxillary supporting cusps) follow a similar embrasure contact pattern, with the exception of the following two cusps:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

|. For the maxillary left central incisor, the notation is given as |

|. For the maxillary left central incisor, the notation is given as | . This numbering system presents difficulties when an appropriate font is not available for keyboard recording of these notations.

. This numbering system presents difficulties when an appropriate font is not available for keyboard recording of these notations.

|. The notation for the right permanent maxillary first molar would be

|. The notation for the right permanent maxillary first molar would be  |. The Palmer notation system is used frequently in the orthodontic literature.

|. The Palmer notation system is used frequently in the orthodontic literature.