4

Class II Division 1 Malocclusion

Introduction

A class II division 1 malocclusion is defined by the presence of a class II incisor relationship with an increased overjet, and either proclined or normally inclined upper incisors. It is the most prevalent arch malrelationship in Caucasian populations, seen in between 15% and 27% of this population (Helm, 1968; Foster and Day, 1974; Proffit et al., 1998). The molar relationship is usually Angle class II, but an increased overjet can occur in the presence of class I molars if the upper incisors are proclined or, rarely, with a class III molar relationship. Molar relationships are usually symmetrical but may be asymmetrical with alterations influenced by local factors. Therefore, a class II division 1 malocclusion should be defined primarily by the incisor relationship.

The skeletal pattern is usually class II secondary to mandibular retrognathia, with the extent of this discrepancy often dictating the severity of the malocclusion (McNamara, 1981). In the vertical dimension, variation across the whole spectrum can be seen, from a hypodivergent facial form with reduced lower face height and increased overbite to hyperdivergent with increased lower face height and reduced overbite or anterior open bite, depending on the extent of the disharmony. Malocclusions associated with an increased Frankfort–mandibular planes angle are generally more challenging to treat orthodontically because of the associated unfavourable downward and backward pattern of mandibular growth and unfavourable soft tissue pattern.

The soft tissues can play a role in the aetiology of a class II division 1 incisor relationship, particularly if the upper incisors rest on or are in front of the lower lip. This is known as a lip trap and can result in proclination of the upper incisors and retroclination of the lower incisors worsening the overjet. If the lower lip is particularly active, resulting in significant retroclination of the lower labial segment, it is described as ‘strap-like’. Proclination of the upper incisors can also lead to protrusion of the upper lip.

In low or average angle cases, the resting position of the lower lip behind the upper incisors reflects lip incompetence. In this situation the lip relationship is sometimes described as potentially competent as it is only the position of teeth that prevents the patient from achieving lip competence without strain. In high angle cases, lip incompetence is usually due to the skeletal lower face height being greater than the lip length; muscular effort is required to achieve competence. The vertical growth pattern is also important in the long-term stability following overjet reduction in these cases. Stability is more likely if the lower lip rests in front of the upper incisors after treatment, which is more likely if the Frankfort–mandibular angle is average or low, with an associated anterior growth rotation. In high angle cases with a backward growth rotation and increased lower face height, even if the overjet is successfully reduced, the lower lip is likely to rest below the upper incisors, which is another reason why high angle class II division 1 malocclusions are difficult to treat.

While the overjet is increased, the overbite can range in depth, but is often incomplete due to the presence of an adaptive pattern of swallowing, secondary to the increased overjet. Dental crowding is also typical, particularly in the lower labial segment if it is retroclined. The maxillary incisors are often proclined and spaced due to the resting position of the lower lip in the presence of a lip trap.

As already outlined, the aetiology of a class II division 1 incisor relationship is often skeletal due to mandibular retrognathia, but can be related to lip position in the presence of a skeletal class I or rarely a class III pattern. It can also be due to a digit sucking habit that persists beyond eruption of the permanent maxillary incisors. An increased overjet can have negative psychosocial implications and is also associated with an increased risk of trauma to the upper labial segment, particularly in children, both of which are indications for treatment (Nguyen et al., 1999).

Treatment is influenced primarily by the extent of the skeletal discrepancy and the dento-alveolar contribution to the overjet. There are essentially three main approaches to the correction of a class II division 1 malocclusion:

- Growth modification: In a growing patient attempts can be made to correct the underlying skeletal discrepancy by utilizing or modifying growth, either with headgear, a functional appliance or a combination of the two. Success is determined by the patient’s co-operation with what can be quite demanding treatment and the direction and extent of growth. Both of these variables are very difficult to predict.

- Orthodontic camouflage: The skeletal discrepancy is accepted and the overjet is corrected by orthodontic tooth movement, primarily uprighting, or retracting the upper incisors and proclining the lower incisors. Space is usually required in the upper arch to do this and can be created by either distalization of the maxillary buccal segments or extraction of maxillary premolars. This is appropriate treatment for a class II division 1 malocclusion on a skeletal class I or mild-to-moderate skeletal class II base in a non-growing individual, but may not be suitable for more severe skeletal class II discrepancies due to the potential negative effects on the soft tissue profile.

- Combined orthodontic–surgical treatment: For those cases with a significant antero-posterior or vertical skeletal component to their malocclusion, where camouflage treatment is not an option, combined orthodontic–surgical treatment is often carried out, with surgical repositioning of the jaws allowing definitive correction of the skeletal discrepancy as part of the treatment plan.

Case 4.1

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Moderate skeletal class II |

| Vertical: | FMPA: Increased |

| Lower face height: Increased | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Incompetent with lower lip acting palatally to maxillary incisors |

| Naso-labial angle: Obtuse | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 6 mm |

| Smiling: 12 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present: |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No restorations or active caries |

| Oral hygiene – periodontal | Moderate with marginal gingivitis in the upper anterior region |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class II division 1 |

| Overjet: 12 mm | |

| Overbite: Average and incomplete | |

| Molar relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Canine relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Centre lines: Coincident | |

| Functional occlusion: Group function | |

| Lower arch | Crowding: Mild |

| Incisor inclination: Average | |

| Upper arch | Crowding: Mild |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Canine position: Line of the arch | |

Summary

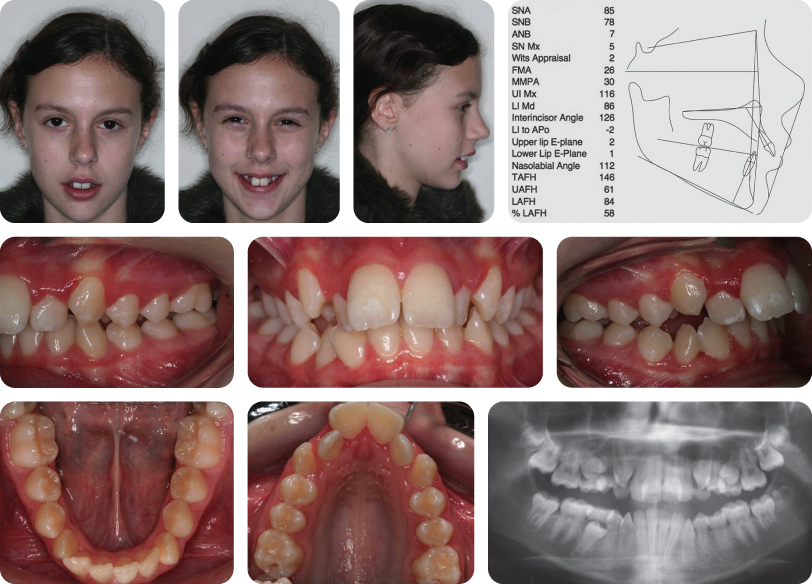

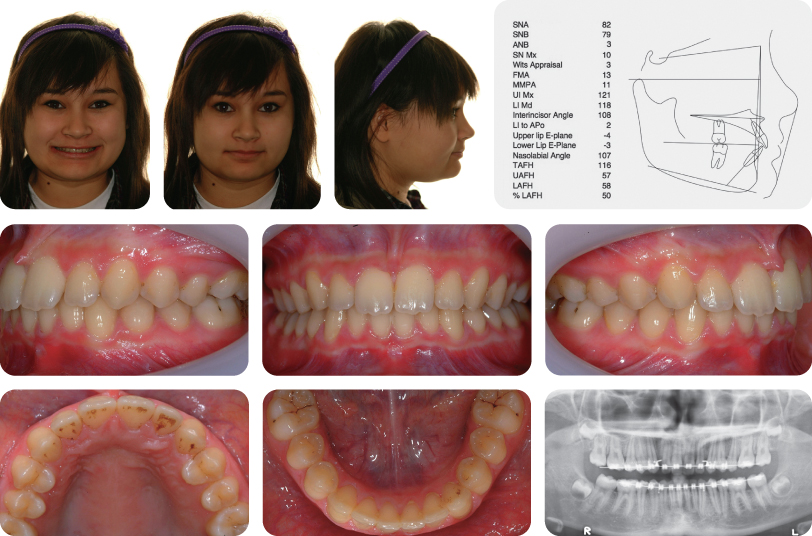

A 12-year-old female presented with a class II division 1 malocclusion on a moderate skeletal class II pattern, with increased vertical dimensions complicated by an increased overjet (12 mm), crowding of both dental arches and teasing in relation to her dento-facial appearance (Figure 4.1).

Why Is the Skeletal Pattern Described As Moderate?

An ANB value of 7 degrees and a Wits value of +2 mm

Treatment Plan

- Improve oral hygiene

- Functional appliance therapy with occipital-pull headgear

- Upper and lower pre-adjusted edgewise appliances with extraction of four second premolars

- Long-term retention

Is There a Relationship between Malocclusion and Teasing/Bullying?

Teeth have been reported as the fourth most common feature to provoke unfavourable social responses, including bullying. Increased overjet is linked with teasing (Shaw et al., 1980) and reduced self-concept. It is also associated with reduced levels of oral health-related quality of life (Johal et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2009). Some improvement in self-concept has been demonstrated in subjects undergoing early overjet reduction (O’Brien et al., 2003). However, prolonged follow-up has failed to show a sustained effect; self-concept is influenced by an array of features.

What Are the Short-Term Effects of Functional Appliances?

Short-term effects of functional appliance therapy are both skeletal and dento-alveolar in nature; but dental effects predominate. In particular, retroclination of maxillary incisors and proclination of mandibular incisors contribute to correction of the incisor relationship (O’Brien et al., 2003). Maxillary restraint and acceleration of mandibular growth are also important in the short-term.

How Do These Changes Contrast with the Long-Term Effects?

Prospective research suggests that prolonged growth modification may not be achievable. These studies have confirmed that skeletal modification is instrumental in producing favourable occlusal change, including overjet reduction and molar correction; however, medium-term follow-up indicates that this growth enhancement may disappear with further maturation (O’Brien et al., 2003; 2009). It appears that mandibular growth potential is largely pre-determined and that our capacity to permanently alter growth of this bone is limited. Nevertheless, occlusal correction tends to be effective and stable.

Why Was This Patient Treated with a Functional Appliance?

- Growing adolescent

- Skeletal class II pattern

- Increased overjet (12 mm)

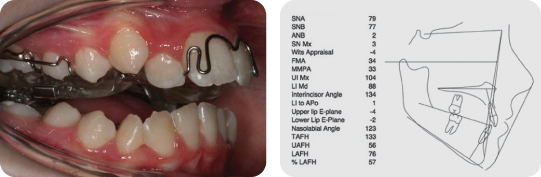

What Type of Functional Appliance Was Used, How Does This Differ From Other Functional Appliances and What Are the Potential Advantages? (Figure 4.2)?

The appliance is a Dynamax appliance developed by Neville Bass (Bass and Bass, 2003).

This appliance consists of an upper removable component, which incorporates Adams cribs on the first molars and first premolars, a midline coffin spring and anterior torque spring on the maxillary central incisors. Mandibular posture is achieved using a lower fixed lingual arch, which has shoulders that project horizontally. As the patient closes, two vertical springs, which project from the upper appliance, ensure anterior posturing of the mandible through avoiding interference with the lower lingual arch. The appliance can be reactivated by adjusting the springs on the upper appliance.

The reported advantages include:

- Simple incremental advancement

- Simultaneous use of a lower fixed appliance

- Control of incisor inclination

- Restriction of vertical facial development.

A recent randomized controlled trial has demonstrated that the Twin Block is a more effective functional appliance than the Dynamax when overjet reduction is evaluated, with a significant increase in the incidence of adverse effects seen with the Dynamax (Thiruvenkatachari et al., 2010).

What Factors Influence the Need for Headgear in Association with Functional Appliance Therapy?

The more severe the class II discrepancy, the more useful headgear support can be. Cases with maxillary excess, either antero-posterior or vertical will also benefit from the use of headgear with a functional appliance. In this case, occipital-pull headgear facilitated overjet reduction by restraining maxillary forward growth. The pre-treatment SNA value of 85 degrees was suggestive of a forward position of the maxilla. Also, the use of headgear, particularly when combined with torqueing spurs, will help prevent tipping of the maxillary incisors and a backwards and downwards rotation of the maxilla, a common side effect of functional appliances. By stabilizing the maxilla, theoretically there is greater chance of antero-posterior mandibular positioning, which is desirable, particularly in a high angle case, as opposed to vertical or rotational change, which is not.

How Do Functional Appliances Work?

Functional appliances harness the forces generated by the oral and facial musculature to produce tooth movement. The principle movements are maxillary incisor retroclination, mandibular incisor proclination and guidance of eruption of the posterior dentitions (distal in the maxilla and mesial in the mandible). Some favourable skeletal change can also occur (maxillary restraint, forward mandibular growth), although these effects are small in comparison to the dento-alveolar changes.

What Types of Functional Appliances Are There?

There are a number of classifications for functional appliances; however, the simplest is to categorize them according to basic design:

- Fixed (e.g. Herbst appliance)

- Removable (e.g. Twin Block, Bionator, Medium Opening Activator)

- Hybrid (e.g. Dynamax appliance).

What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Fixed Functional Appliances?

- Guaranteed wear of the appliance

- Improved compliance and completion rate

However, these advantages are tempered by:

- Greater onus on oral hygiene

- Increased cost

- Greater chair-side manipulation

- Higher breakage rate.

What Factors Influence the Choice of a Specific Functional Appliance?

- Anticipated compliance

- Vertical skeletal pattern

Fixed functional appliances are preferable where co-operation is likely to be poor. Patients with increased lower anterior face height may benefit from restraint of vertical maxillary growth; the addition of high pull headgear and use of specific functional appliances (Teuscher, van Beek, Dynamax) have been proposed to address this problem. Conversely, with a reduced lower anterior face height, the expression of vertical facial growth and posterior tooth eruption can be more favourable; consequently, specific appliances, including the Medium Opening Activators and Modified Twin Block, are useful.

Why Were Fixed Appliances Used in This Case (Figure 4.3)?

Fixed appliances were used after the functional phase of treatment to align the arches, finish and detail the occlusion. Removal of four second premolars was considered necessary to alleviate the dental crowding. Consequently, fixed appliances were also required to close the remaining extraction spaces after alignment. Achievement of good buccal segment inter-digitation makes prolonged stability of class II correction more likely (Pancherz, 1991) (Figure 4.4).

Case 4.2

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Moderate skeletal class II |

| Vertical | FMPA: Reduced |

| Lower face height: Reduced | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Incompetent with lower lip resting palatally to maxillary incisors |

| Upper lip length: 17 mm | |

| Naso-labial angle: Average | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 3 mm |

| Smiling: 8 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present: |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No restorations or active caries |

| Oral hygiene | Good |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class II division 1 |

| Overjet: 11 mm | |

| Overbite: Increased and complete | |

| Molar relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Canine relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Centre lines: Coincident with each other and the facial midline | |

| Functional occlusion: Group function | |

| Lower arch | Spaced |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Curve of Spee: Increased | |

| Upper arch | Spaced |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

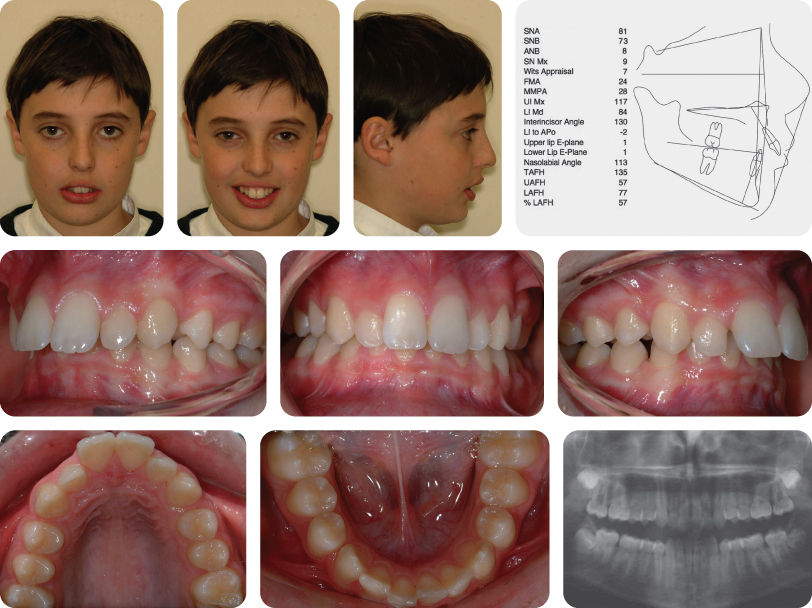

Summary

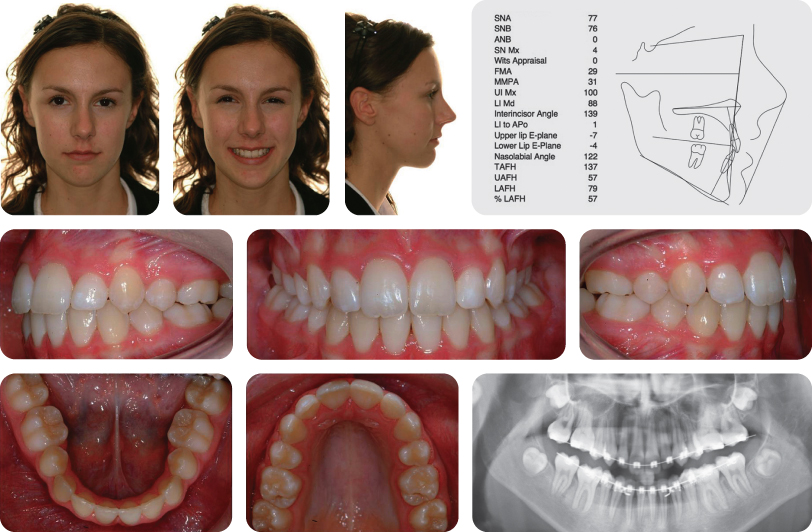

An 11-year-old female presented with a class II division 1 malocclusion on a moderate skeletal class II pattern with reduced vertical dimensions complicated by an increased overjet (11 mm), increased overbite, generalized spacing and bi-maxillary proclination (Figure 4.5).

Treatment Plan

- Modified Twin Block functional appliance with sectional lower fixed appliance

- Upper and lower pre-adjusted edgewise appliances

- Long-term retention

The final result of treatment is shown in Figure 4.6.

What Is the Likely Aetiology of This Malocclusion?

The aetiology of this malocclusion is multi-factorial. The moderate skeletal class II discrepancy resulted in an increased overjet and class II molar relationship. The overjet was exacerbated by the presence of a lower lip trap. The generalized spacing was a result of an underlying dento-alveolar disproportion. This was compounded by bi-maxillary proclination, which arose due to resting soft tissue pressures and dento-alveolar compensation.

Why Was a Lower Fixed Appliance Placed in Conjunction with the Functional Appliance?

- To correct the inclination of the mandibular incisors

- To facilitate optimum skeletal changes with functional appliance therapy

- Consolidation of lower arch space

What Is Dento-Alveolar Compensation?

- A natural alteration in the position of the dentition to limit the occlusal effect of an underlying skeletal discrepancy.

- It can occur in all three planes of space.

- It is typically most pronounced in class III malocclusion with retroclination of mandibular incisors and proclination of the maxillary incisors compensating for a skeletal class III discrepancy.

How Long Does Functional Appliance Therapy Take?

At this stage there is no evidenced-based answer to this question, with treatment time being dictated by operator preferences and the individual response of patients to treatment. However, it usually takes around 6–12 months. Shorter periods of appliance wear are likely to be less stable than longer courses of treatment.

How Can the Transition between Functional and Fixed Appliances Be Managed?

- Integration of functional and fixed appliances (e.g. Herbst appliance)

- Continuation of functional appliance wear at night only

- Use of headgear

- Inter-arch class II elastic traction following fixed appliance placement

Is This Treatment Result Likely to Be Stable (Figure 4.6)?

The prognosis for long-term stability of class II correction is good in this case, as the new maxillary incisor position will be controlled by the lower lip following the achievement of lip competence. Prolonged compliance with the retention regimen will be required to maintain intra-arch alignment, particularly in view of the pre-treatment spacing and bi-maxillary proclination.

Case 4.3

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Moderate skeletal class II |

| Vertical | FMPA: Average |

| Lower face height: Average | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Incompetent with lower lip acting palatally to maxillary incisors |

| Upper lip length: 18 mm | |

| Naso-labial angle: Obtuse | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 5 mm |

| Smiling: 11 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No restorations or active caries |

| Oral hygiene | Good |

Summary

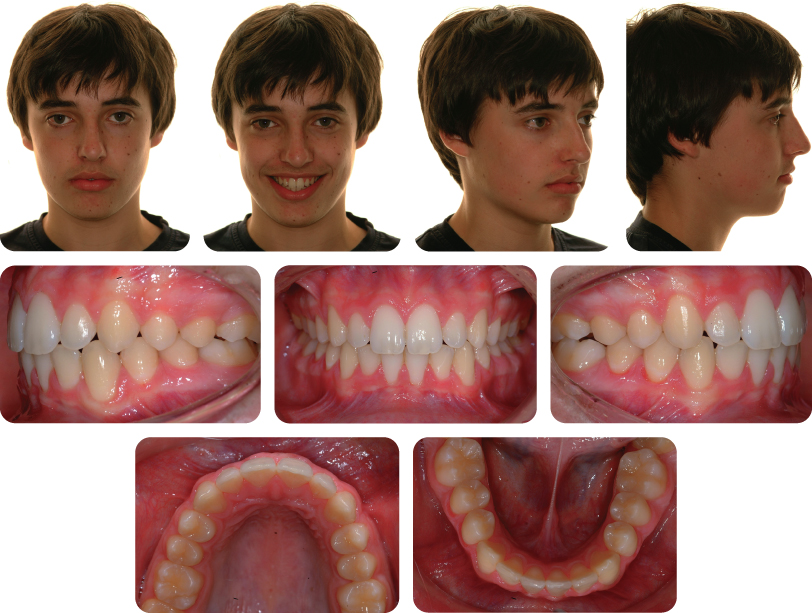

A 12-year-old male presented with a class II division 1 incisor relationship on a moderate skeletal class II pattern with average vertical dimensions complicated by an increased overjet (11 mm) and overbite with well-aligned dental arches (Figure 4.7).

Summarize the Occlusal Features of This Case

- Incisor relationship: Class II division 1

- Overjet is increased (11 mm)

- Overbite increased and complete

- Molar relationship: Class II bilaterally

- Canine relationship: Class II bilaterally

- Centre line discrepancy of 2 mm (1/3 tooth unit) (Upper dental centre line correct to facial midline, lower dental centre line deviated 2 mm to right)

- Lower arch:

- Crowding: Mild

- Incisor inclination: Average

- Curve of Spee: Increased

- Upper arch:

- Crowding: Mild

- Incisor inclination: Proclined

Does the Cephalometric Analysis Agree with the Clinical Appearance?

Yes. The cephalometric analysis is suggestive of a skeletal class II discrepancy (ANB = 8 degrees, Wits appraisal = 7 mm) with mandibular retrognathia (SNA = 81 degrees but SNB = 73 degrees); however, the vertical skeletal relationship is within the normal range (maxillary–mandibular planes angle [MMPA] = 28 degrees).

Treatment Plan

- Modified Twin Block functional appliance to reduce the overjet

- Upper and lower pre-adjusted edgewise appliances to align and co-ordinate the dental arches

- Long-term retention

Figure 4.8 Shows the Occlusion After 7 Months of Twin Block Therapy. What Is Characteristic about This Appearance?

The overjet has reduced but bilateral lateral open bites are present. Overjet reduction usually takes place faster than correction of the vertical relationship. The appearance of bilateral lateral open bites is therefore commonly seen. Additional time will be required for these to close; however, overjet reduction will need to be maintained. Night-time wear of the appliance, occlusal trimming of the blocks on the Twin Block or the use of a simple removable appliance with an inclined anterior bite plane, which allows vertical development of the mandibular buccal dentition whilst maintaining the reduced overjet, can all be used.

When Is the Best Time to Use a Functional Appliance?

Functional appliances are typically used in the late mixed dentition in growing patients. Prospective research has focused on the ability of functional appliances to modify mandibular growth in pre-pubertal children and overall, it seems that functional appliances are most efficient when used at this stage. Consequently, the functional phase can then be followed by fixed appliances to detail the occlusion in a single phase.

The chronological age corresponding to maximal pre-pubertal growth is variable, but generally treatment is commenced at 10–12 years of age in females and 11–14 years of age in males. This time period tends to coincide with establishment of the late mixed or early permanent dentition, permitting optimal retention of tooth-borne appliances.

Is There a Greater Risk of Trauma with an Increased Overjet?

- An overjet exceeding 3 mm has an approximately two-fold increased risk of sustaining incisor trauma (Nguyen et al., 1999).

- In children with an overjet exceeding 9 mm, up to 45% have sustained traumatic dental injury (Todd and Dodd, 1985).

- Risk of trauma is gender-specific, with excessive overjet more likely to be linked to trauma in females.

Has Orthodontic Treatment been Shown to Reduce the Incidence of Dental Trauma?

A large prospective clinical study has failed to confirm the association between interceptive orthodontic treatment in 9–10-year olds with an overjet of 7 mm or more and prevention of trauma (Koroluk et al., 2003). This finding may be related to the fact that traumatic injury often arises in the mixed dentition, before treatment would typically commence. Indeed, 29% had already been affected by trauma before participating in this research study. Therefore, from a public health viewpoint, initiating treatment in all children with excessive overjets at an early stage to prevent trauma would be inappropriate.

What Soft Tissue Factor Contributed to the Increased Overjet in This Case?

A lower lip trap, with the lip acting palatal to the maxillary incisors, resulted in excessive proclination of the central incisors. The lip trap may arise due to mandibular retrognathia; this in turn, increases maxillary incisor proclination with an additive effect on the overjet. The lip trap has been eliminated following treatment (Figure 4.9). Incompetent lips may also arise due to reduced tonicity, predisposing to proclination of the incisors. Asymmetric inclination changes can also occur due to resting lip position (Figure 4.10).

Case 4.4

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Mild skeletal class II |

| Vertical | FMPA: Average |

| Lower face height: Average | |

| Transverse | Facial asymmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Incompetent with lower lip acting behind the maxillary incisors |

| Naso-labial angle: Average | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 4 mm |

| Smiling: 10 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health (restorations, caries) | Good |

| Oral hygiene – periodontal | Good oral hygiene |

| Lower arch | Crowding: Mild |

| Incisor inclination: Average | |

| Curve of Spee: Average | |

| Upper arch | Crowding: Mild |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Canine position: Line of the arch | |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class II division 1 |

| Overjet: Increased (10 mm) | |

| Overbite: Average and incomplete | |

| Molar relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Canine relationship: Class II bilaterally | |

| Centre lines: Maxillary centre line is 1 mm to the left side, the lower is coincident with the mid-facial axis | |

| Functional occlusion: Group function | |

Summary

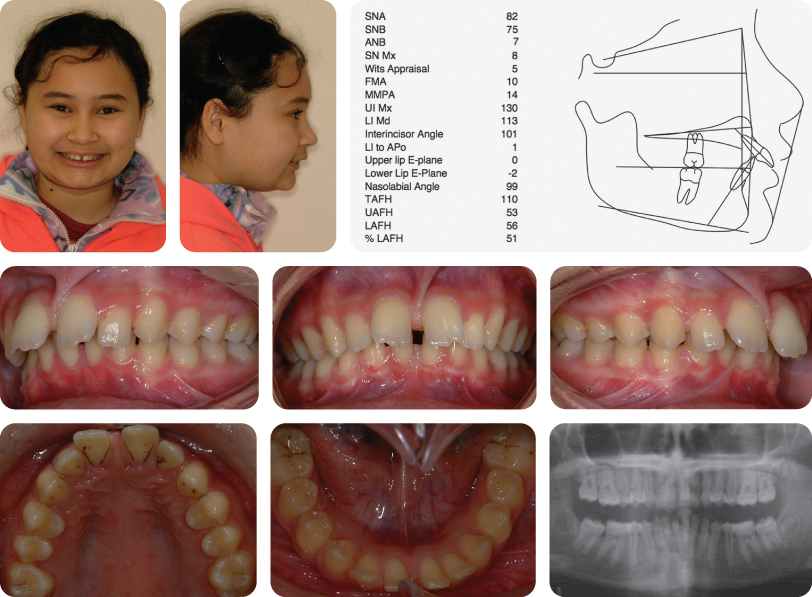

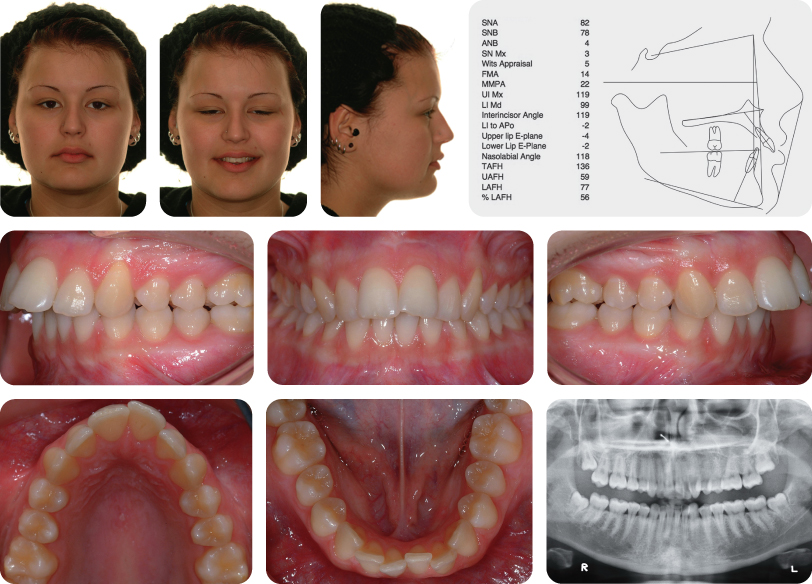

An 18-year-old female presented with a class II division 1 malocclusion on a mild skeletal class II pattern with average vertical dimensions, an increased overjet of 10 mm and mild crowding of both dental arches (Figure 4.11).

Treatment Plan

- Upper and lower pre-adjusted edgewise appliances with extraction of maxillary first premolars bilaterally

- Temporary anchorage devices (TADs) between the maxillary second premolars and first molars (Figure 4.12)

- Long-term retention

What Is the Primary Aim of Treatment in This Case?

The primary aim of treatment was overjet reduction to camouflage the underlying skeletal class II discrepancy. The anchorage demand to facilitate overjet reduction was high because the pre-treatment molar relationship was a full unit class II bilaterally and the overjet was significantly increased. Consequently, maxillary first premolars were removed to maximize retraction of the upper labial segment. Some proclination of the mandibular incisors was also planned to reduce the maxillary arch anchorage requirement. In addition, TADs were placed mesial to the first permanent molars to prevent mesial migration of the maxillary buccal segments whilst retracting the maxillary incisors maximally. Consequently, the class II molar relationship was maintained and both the canine and incisor relationships were corrected to class I (Figure 4.13).

What Is Anchorage?

Anchorage is the resistance to unwanted tooth movement. In this case, anchorage was necessary to prevent mesial migration of the maxillary buccal segments during overjet reduction.

How May Antero-Posterior Anchorage Be Supplemented to Facilitate Overjet Reduction?

- Intra-arch mechanics:

- Headgear

- TADs

- Nance palatal arch

- Transpalatal arch

- Inter-arch mechanics:

- Functional appliances

- Class II elastics

- Fixed class II correctors

What Are the Limitations of Headgear?

- Patient compliance. Headgear wear of up to 14 hours per day may be required. The duration of wear is often less than half this time (Brandao et al., 2006). Compliance is particularly poor in adults.

- Risk of injury. Reports of iatrogenic injury, including blindness, have been attributed to headgear injury, although this is extremely rare (Postlethwaite, 1989).

- For maximum effect, residual maxillary growth is required.

- Successful distal molar movement is difficult after maxillary second permanent molars have erupted.

How May Compliance with Headgear Be Improved?

- Encouragement and rewards

- Headgear charts (Cureton et al., 1993)

- Headgear timers

- Patient should be actively growing

What Are the Risks of TAD Use?

- Root damage

- Failure of the TAD

The risks of TADs would appear to be relatively minor, with evidence to suggest root damage relating to iatrogenic placement is transient. Nevertheless, it is suggested that patients are counselled on the advantages, disadvantages, risks and alternatives prior to TAD placement, and appropriately consented. A national audit is currently being undertaken by the British Orthodontic Society to investigate the relative merits of TAD use in the UK.

What Are the Problems Associated with Extracting Premolar Teeth in the Maxillary Arch Only?

Space closure can be difficult, particularly if the lower incisor teeth are proclined during treatment. The main problem originates from the fact that a single maxillary premolar tooth width is often larger than a single tooth ‘unit’. Therefore, with the overjet reduced, the molars in a full unit class II relationship and the canines class I, a small tooth size discrepancy can remain, which can result in a small amount of residual space. This can be completely closed by bringing the molars forward into a ‘super’ class II relationship or rotating the maxillary premolars slightly to increase their relative width.

Case 4.5

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Moderate skeletal class II |

| Vertical | FMPA: Reduced |

| Lower face height: Reduced | |

| Transverse | Facial asymmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Incompetent with lower lip acting palatally to maxillary incisors |

| Naso-labial angle: Average | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 2 mm |

| Smiling: 5 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No restorations or active caries |

| Oral hygiene – periodontal | Good |

| Lower arch | Crowding: Moderate |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses