6

Class III Malocclusion

Introduction

A class III malocclusion is defined by the presence of a class III incisor relationship, which may range from a reduced overjet or edge-to-edge incisor relationship to a frank reversed overjet, the severity typically reflecting the underlying skeletal pattern. However, in some cases, considerable dento-alveolar compensation can be seen masking the skeletal discrepancy. The maxilla is often deficient in all three spatial planes, which may lead to significant crowding and the presence of posterior crossbites, which are often bilateral and exacerbated by an antero-posterior skeletal discrepancy. A full range of overbite depth may also occur and can be associated with an anterior displacement on closure from the retruded contact position (RCP) to inter-cuspal position (ICP), making the skeletal class III pattern appear more severe than it actually is. The term ‘pseudo-class III’ has been coined for this situation where an anterior displacement disguises what is in fact an underlying skeletal class I base relationship.

However, the skeletal pattern is usually class III, and unlike most skeletal class II patterns, which are primarily due to mandibular deficiency, skeletal class III discrepancies can be related to maxillary retrusion, mandibular prognathism or a combination of these two features with a large range of individual variation (Guyer et al., 1986; Battagel, 1993). The extent of the antero-posterior skeletal discrepancy is usually the defining feature of the malocclusion. In the vertical dimension, variation is common, with patients presenting with a full range of vertical growth patterns from hypo- to hyper-divergent facial types. Skeletal asymmetries, particularly in conjunction with mandibular prognathism, are also relatively common in class III malocclusions (Severt and Proffit, 1997).

The prevalence of class III malocclusion is generally low in Western societies, being reported at 3–5%. There is a higher prevalence in Oriental populations. The aetiology is multifactorial, although there certainly appears to be a familial tendency, particularly in relation to mandibular prognathism (Xue et al., 2010). Patients with a history of a repaired cleft lip and palate exhibit a higher incidence of class III malocclusion, which is thought often to be iatrogenic in nature and related to scarring from the primary surgical repair in infancy.

Treatment planning in class III cases is notoriously difficult and influenced primarily by the skeletal discrepancy, size of the reverse overjet, extent of crowding, degree of existing dento-alveolar compensation and the likelihood of future growth. However, as with other types of malocclusion, there are really three main approaches to the correction of a class III malocclusion:

- Growth modification: Class III malocclusions usually present in the early mixed dentition following eruption of the permanent incisors. A decision is required at this stage as to whether correction of the incisor relationship and the underlying skeletal discrepancy should be attempted with interceptive treatment. This treatment can be aimed at modifying growth, either with reverse-pull headgear (with or without maxillary expansion) or a functional appliance. Success of this treatment will depend on establishing a positive overjet and overbite, and the nature and direction of future growth. An alternative strategy is to attempt mandibular growth suppression; however, long-term mandibular growth restraint using chin caps has met with little success (Sugawara et al., 1990).

- Orthodontic camouflage: Definitive treatment can be carried out in the permanent dentition if the skeletal discrepancy is mild and facility for dento-alveolar compensation still exists. While removable appliances and sectional fixed appliances are useful to camouflage the incisor relationship as an interceptive measure in the mixed dentition, comprehensive correction in the permanent dentition typically involves the use of fixed appliances with class III inter-arch elastic traction. Extractions are often required in the upper arch of class III cases because of crowding; however, when attempting camouflage, lower arch extractions are also commonly required to create space for retraction of the lower labial segment. Mid-arch extractions are usually undertaken in both arches, although in adult patients a single lower incisor extraction can be considered. The prolonged success of treatment depends on establishing a positive overjet and overbite, and the pattern and magnitude of further growth.

Orthodontic camouflage is not appropriate in the presence of a severe skeletal class III relationship with compensated incisors (i.e. proclined maxillary incisors and retroclined mandibular incisors). Further growth is also an important consideration as mandibular prognathism tends to deteriorate during the adolescent growth period and beyond (Battagel, 1993). If orthodontic camouflage is attempted in a case who subsequently grows unfavourably and requires surgery to definitively correct the class III relationship, lower incisor decompensation will subsequently be required as part of the pre-surgical set-up. This is difficult to achieve if teeth have been previously extracted in the lower arch without re-opening space. Several studies have attempted to provide cephalometric guidelines to distinguish cases who will be suitable for camouflage, but it is sensible in significant class III cases to delay final treatment planning until near the end of adolescent growth (Kerr et al., 1992; Burns et al., 2010). - Surgery: For those cases with a significant antero-posterior or vertical skeletal component to their malocclusion, combined orthodontic–surgical treatment is required for definitive correction. Surgery should ideally be deferred until growth is complete; otherwise continued mandibular growth will result in skeletal relapse. Therefore, monitoring mandibular growth during adolescence prior to committing to a surgical plan is considered best practice. Superimposition of serial cephalograms to confirm that active growth has reduced to acceptable levels has been advocated prior to instituting treatment (Fudalej et al., 2007).

Case 6.1

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Skeletal class I |

| Vertical | FMPA: Average |

| Lower face height: Average | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Competent with protrusive lower lip |

| Naso-labial angle: Normal | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 2 mm |

| Smiling: 5 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy, with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No active caries and good oral hygiene |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class III |

| Overjet: −2 mm | |

| Overbite: Average and incomplete | |

| Molar relationship: Class I bilaterally | |

| Anterior displacement on closure from RCP to ICP Centre line: Mandibular to the right by 2 mm | |

| Lower arch | Crowding: Aligned |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Upper arch | Crowding: Mild crowding |

| Incisor inclination: Upright | |

| Canine position: Palpable buccally | |

Summary

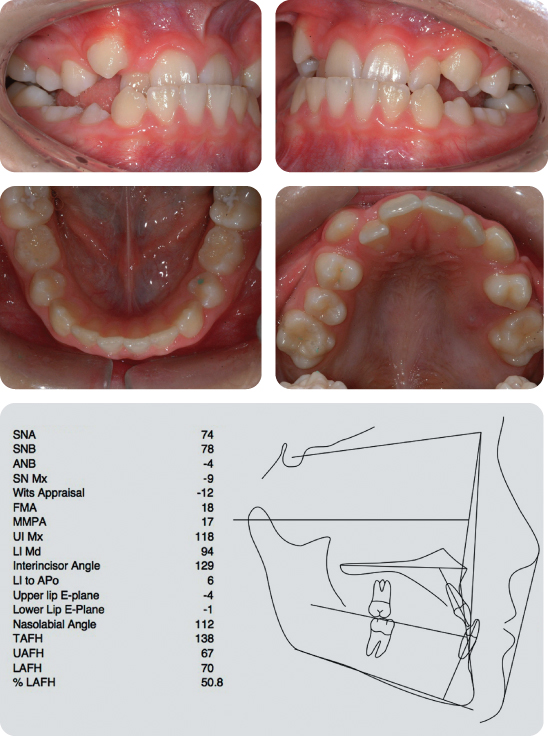

A 9-year-old female presented in the mixed dentition with a class III malocclusion on a skeletal class I base with an average lower face height, mild crowding and an anterior crossbite (Figure 6.1).

Treatment Plan (Figure 6.2)

The aims of treatment were to correct the anterior crossbite and eliminate the displacement.

A pre-adjusted edgewise appliance was placed on the upper incisors, primary canines and first permanent molars. The initial aligning archwire was a 014-inch heat-activated nickel–titanium fully engaged into the brackets on the maxillary incisors. The wire was supported in the buccal segments with 0.8 mm steel tubing to prevent distortion.

At the second visit, the initial archwire was re-activated. At the third visit a 0.020 × 0.020-inch heat-activated nickel–titanium archwire was placed and the glass ionomer bite plane removed. Thereafter, a 019 × 025-inch beta titanium archwire was placed with a vertical offset to extrude the upper central incisors and establish a positive overbite. The appliance was then removed (Figure 6.3).

Why Was Treatment Carried Out in the Mixed Dentition?

An anterior crossbite with an associated displacement is an indication for early orthodontic interception, particularly if the displacement is greater than 2 mm. An anterior crossbite can result in occlusal wear and gingival recession in the presence of an associated displacement.

Why Was Glass Ionomer Cement Placed on the Occlusal Surface of the Posterior Dentition?

This was placed to eliminate potential occlusal interferences to tooth movement.

What Retention Regime Should Be Used?

In this case, no retention was prescribed, as a positive overbite and overjet was established which should maintain the new incisor position (Figure 6.3).

What Were the Advantages of Using a Fixed Appliance in this Case?

In the mixed dentition, a fixed appliance can result in the rapid correction of a crossbite, is well tolerated and is less dependent on compliance than a removable appliance (McKeown and Sandler, 2001). Fixed appliances also offer three-dimensional control, including vertical repositioning, which is key to creating a positive overbite at the end of treatment (Skeggs and Sandler, 2002). Another advantage of a fixed appliance is that it can allow for space creation if necessary. In this case, the maxillary central incisors were actively extruded to create a positive overbite at the end of treatment to improve long-term stability.

What Other Methods Are Available to Correct an Anterior Crossbite?

Removable appliances can also be used, although these are reliant on good retention and compliance, and are only capable of tipping teeth. As such, removable appliances are most effective with only one or two teeth in crossbite, with space available to procline them. Alternatively, a functional appliance, such as a Functional Regulator or reverse Twin Block, can be used, although these also depend on good co-operation.

Case 6.2

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Moderate skeletal class III |

| Vertical | FMPA: Average |

| Lower face height: Average | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Competent with protrusive lower lip |

| Naso-labial angle: Normal | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 2 mm |

| Smiling: 5 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No active caries and good oral hygiene |

| Lower arch | Aligned |

| Incisor inclination: Upright | |

| Upper arch | Severely crowded. UL5 impacted palatally |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Canine position: Palpable buccally | |

Summarize the Occlusal Findings

- Incisor relationship: Class III

- Overjet: −3 mm

- Overbite: Average and incomplete

- Molar relationship: 1/4 unit class III bilaterally

- No anterior displacement on closing from RCP to ICP

Summary

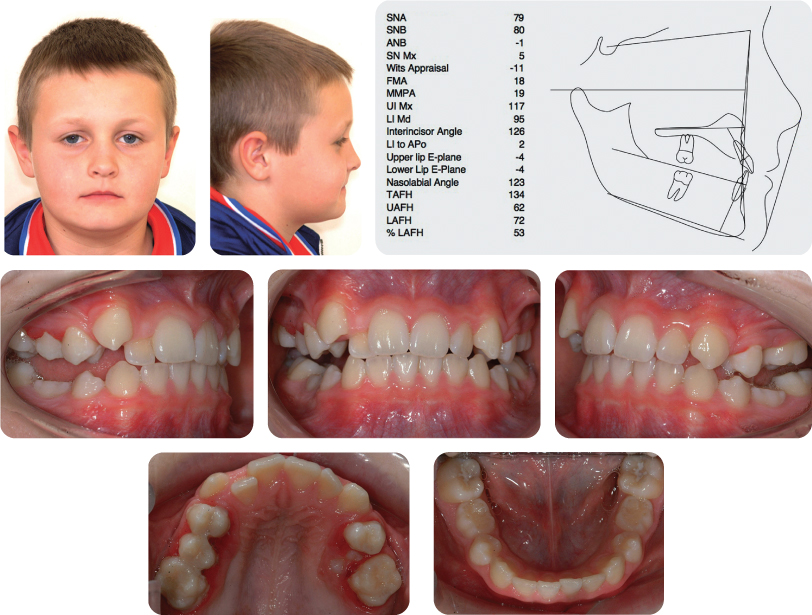

A 10-year-old male presented with a class III malocclusion on a moderate skeletal class III pattern with average lower face height, severe crowding, an impacted UL5 with an anterior crossbite without displacement in the late mixed dentition (Figure 6.4).

Treatment Plan

A bonded rapid maxillary expansion device with a HYRAX screw was initially placed and the patient asked to activate the screw once daily for 10 consecutive days. Thereafter, protraction headgear was fitted and an anterior force applied to the maxilla via elastics between hooks on the bonded appliance and the facemask of the protraction headgear. The force was increased incrementally over a period of 8 weeks to 400 g bilaterally and the position of the bar on the facemask adjusted to direct the force parallel to the occlusal plane, limiting rotational effects on the maxilla. The patient was instructed to wear the facemask for a minimum of 16 hours daily (Figure 6.5).

Comment on the Principles and Design of Protraction Headgear

Protraction headgear is not a new innovation in orthodontics, having been originally described over a century ago. However, it was re-introduced and popularized by Delaire in the early 1970s. The principles are straightforward and involve applying a force to an appliance bonded or banded to the maxilla via a frame or facemask that is primarily supported on the forehead and chin. The facemask either consists of a frame that sits lateral to the cheeks, as originally described by Delaire, or a single midline rod based on a design by Petit. With either of these appliances, the principle is the same – a force of around 400 g is applied bilaterally using heavy elastics.

Why Is Protraction Headgear Often Used in Combination with Rapid Maxillary Expansion?

Protraction headgear is often preceded by rapid maxillary expansion (RME) because in many class III malocclusions the maxilla is also narrow in the transverse plane, resulting in crowding and a posterior crossbite. Theoretically, the combined use of RME will also loosen or disengage the circum-maxillary sutures, which in theory facilitates downward and forward movement of the maxillary complex under the force of the headgear (Haas, 1973). However, current evidence would suggest that this combination does not necessarily improve maxillary advancement with protraction headgear (Vaughn et al., 2005).

What Is the Rationale for Using Protraction Headgear?

The majority of class III malocclusions seen in juveniles and adolescents who have an underlying skeletal component will demonstrate some maxillary hypoplasia (Guyer et al., 1986). Ideally, treatment in these cases should be aimed at redirecting and stimulating maxillary antero-posterior growth. One way of achieving this is with the use of extra-oral force in the form of protraction headgear. This is designed to give an ‘orthopaedic’ effect, achieving skeletal change in addition to dento-alveolar movement. The facemask is worn for as close to 24 hours per day as possible, until a positive overjet has been achieved. In this case, the overjet was corrected in 9 months, at which stage it was +4 mm (Figure 6.6).

How Has this Occlusal Correction Been Achieved?

There has been some forward movement of the maxilla (SNA has increased from 74 to 79 degrees) and this has been accompanied by a clockwise rotation of the maxilla (SN-Mx plane has changed from −9 to +5 degrees) and mandible. Interestingly, maxillary incisor inclination has remained essentially the same (UI-Mx, 118 degrees at the start versus 117 degrees at the end).

The bonded expansion appliance was removed and the patient underwent a course of fixed appliance therapy in the maxillary arch to create space for and align the UL5 (Figure 6.7 and Figure 6.8).

When Should Protraction Headgear Be Used?

Protraction headgear is indicated in class III malocclusion associated with maxillary hypoplasia. Use of this appliance appears to be more effective in pre-adolescent (under the age of 10 years) patients than adolescents (Suda et al., 2000).

Are Any Class III Patients Unsuitable for Protraction Headgear?

Patients who present with frank mandibular prognathism are not suitable for protraction headgear therapy. Various other treatment techniques have been described for these patients, including the use of chin caps in an attempt to control mandibular growth. However, even with prolonged treatment, in the long-term this has little effect on the underlying prognathic growth pattern (Sugawara et al., 1990).

What Are the Main Effects of Protraction Headgear?

Protraction headgear therapy will usually result in forward displacement of the maxillary complex of 1–3 mm and a downwards and backwards rotation of the mandible (Kim et al., 1999; Ngan et al., 1998). This will result in an increase in the SNA angle, a decrease in SNB and an increase in ANB. Treatment will also produce dento-alveoler compensation, with proclination of maxillary incisors and some retroclination of the mandibular incisors.

One problem with many of the studies that have been carried out to investigate the effects of protraction headgear has been the lack of an appropriate control group or the use of historical class I or class III controls from longitudinal cephalometric growth studies. Some investigations have tried to overcome this by having each subject act as his or her own control, using the pre-treatment period to measure growth (Ngan et al., 1998), although this is not ideal.

How Stable Is this Treatment?

Following treatment, a class III growth pattern will tend to re-impose itself (Baccetti et al., 2000) with 25–30% of patients exhibiting some relapse following successful protraction headgear therapy. Relapse appears to be primarily related to mandibular growth (Hagg et al., 2003; Wells et al., 2006). Unfavourable long-term outcomes are also associated with patients who exhibit an increased vertical growth pattern and in those starting treatment after the age of 10 years (Baccetti et al., 2004; Hagg et al., 2003).

Case 6.3

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Mild skeletal class III |

| Vertical | FMPA: Average |

| Lower face height: Average | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence: Competent with protrusive lower lip |

| Naso-labial angle: Normal | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 2 mm |

| Smiling: 5 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No active caries and good oral hygiene |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class III |

| Overjet: −3 mm | |

| Overbite: Average and incomplete | |

| Molar relationship: Class I bilaterally | |

| Anterior displacement on closing from RCP to ICP | |

| Lower arch | Crowding: Aligned |

| Incisor inclination: Proclined | |

| Upper arch | Crowding: Aligned |

| Incisor inclination: Upright | |

| Canine position: Palpable buccally | |

Summary

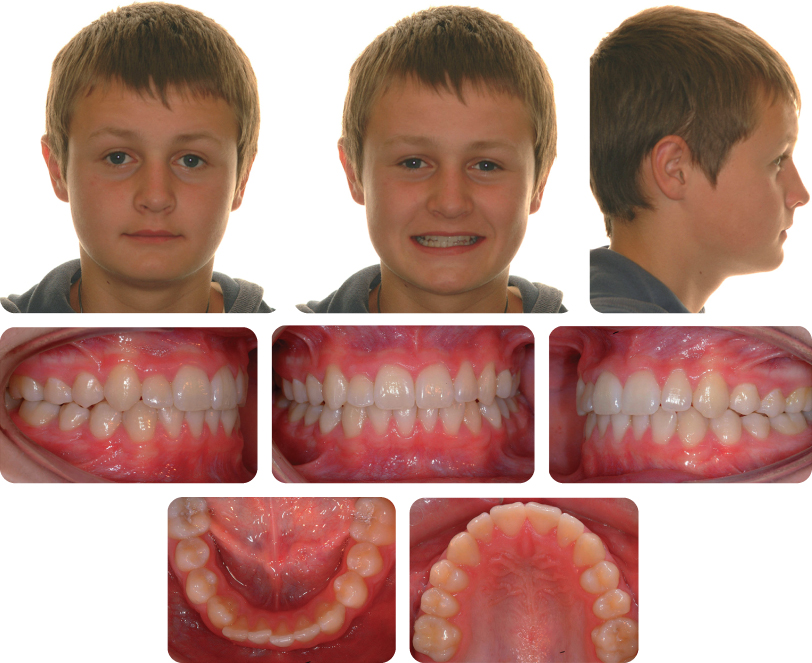

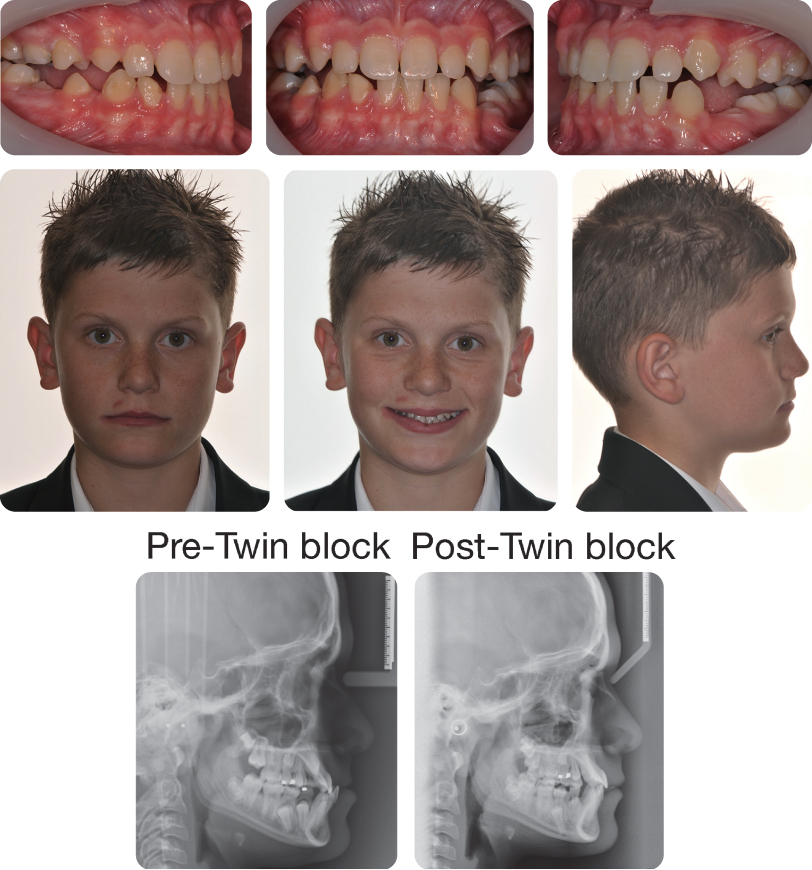

An 11–year-old male presented with a class III malocclusion on mild skeletal class III base with average lower face height, well aligned arches and an anterior crossbite with a displacement, in the late mixed dentition (Figure 6.9).

Treatment Plan

The aims of treatment were correction of the anterior crossbite and elimination of the displacement.

The patient was successfully treated with a modified Twin Block functional appliance for approximately 6 months (Figure 6.10). The design included cantilever springs behind the upper incisors, a midline expansion screw, a lower labial bow and intersecting blocks at 70 degrees with a vertical height of 7 mm. The patient was instructed to wear the appliance on a full-time basis initially, activating the midline expansion screw twice a week. On the second visit the cantilever springs were activated to procline the upper labial segment.

Why Are Functional Appliances Not Routinely Used in the Treatment of Class III Malocclusions?

Functional appliances are routinely used for the correction of class II malocclusions. However, whilst numerous appliances have been described for the treatment of class III malocclusions, none is in routine use. This is partly because the majority of class II malocclusions present with some degree of mandibular retrognathia. Advocates of functional appliances would argue that they stimulate mandibular growth and thereby make a significant contribution to correction of this type of malocclusion. However, class III malocclusions are more disparate, presenting with maxillary hypoplasia, mandibular prognathism or a combination of these (Guyer et al., 1986). While it is possible to advance the maxilla using extra-oral force, control of mandibular prognathism is more difficult. Prolonged chin cap therapy has been shown to have a positive short- term effect on growth. However, following treatment, catch-up mandibular growth has been observed as the original growth pattern is re-established (Sugawara et al., 1990). Nevertheless, some patients with class III malocclusion are amenable to treatment using a functional appliance, and with careful case selection can be treated successfully.

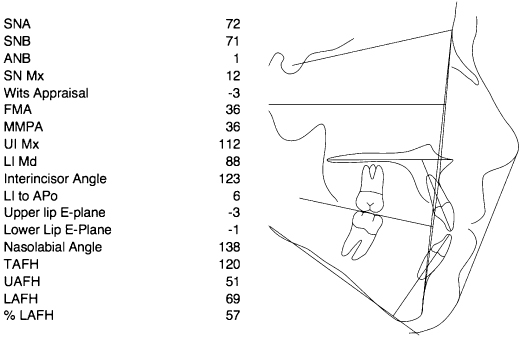

What Were the Main Effects of Treatment in this Case (Figure 6.11)?

The main effects of treatment were proclination of the upper labial segment, retroclination of the lower labial segment and some downward and backward rotation of the mandible. Following correction of the anterior crossbite, the appliance was discontinued to allow closure of the lateral open bites as the positive overbite and overjet that were achieved were judged to be self-retaining.

What Factors Determine Whether Interceptive Treatment Is Attempted in Class III Malocclusions?

The decision to treat a growing class III malocclusion is a difficult one and depends on the underlying aetiology, predicted future growth and the degree of dento-alveolar compensation present, which in turn indicates how much further compensation is possible. Indicators that early correction is possible include the presence of:

- Anterior mandibular displacement

- Average or increased overbite

- Average or reduced lower face height

- Upright or proclined lower incisors

- Upright or retroclined upper incisors.

The present case had these features; such a malocclusion has been described as a ‘pseudo-class III’, implying that it is essentially is skeletal class I but appears to be skeletal class III due to the anterior displacement. Several studies have tried to establish pre-treatment predictors for those class III malocclusions that will be treatable orthodontically as opposed to surgically (Kerr et al., 1992; Schuster et al., 2003). However, the main determinant is future growth, particularly in the vertical dimension.

How Do Functional Appliances Work in the Treatment of Class III Malocclusions?

The mode of action of functional appliances for class III correction has been subject to some limited retrospective investigation. This has shown that correction is achieved primarily by dental movement (Kidner et al., 2003; Loh and Kerr, 1985; Ulgen and Firatli, 1994). There is no sustained effect on growth of either the maxilla or mandible, although there is a reduction in SNB and an increase in ANB due to the backwards and downwards rotation of the mandible and an increase in lower face height. Therefore, this type of treatment is inappropriate for high angle cases with an already increased FMPA.

Are There Any Alternative Methods of Treatment?

Accepting that the effects of this type of treatment are dento-alveolar, other treatment modalities include:

- Removable appliances with palatal springs: The problem with using an upper removable appliance is retention; on activation of the palatal springs, the appliance is displaced vertically. With the reverse Twin Block, by occluding with the lower component of the appliance, the upper plate is re-seated and activated. Therefore, simple upper removable appliances are only effective with one or two teeth in crossbite.

- Fixed appliances: Use of a fixed appliance to correct a class III incisor relationship with a displacement can be effective and avoids the problems of compliance associated with removable appliances.

How Stable Is this Treatment?

The determinant for initial stability will be a positive overbite and overjet at the end of treatment following elimination of the anterior displacement. In the long-term, stability is reliant on the magnitude and direction of mandibular growth. With correct case selection, avoiding treatment in class III malocclusions with an overtly skeletal aetiology, stability is more predictable.

Case 6.4

| Extra-oral | |

| Skeletal relationship | |

| Antero-posterior | Mild skeletal class III |

| Vertical | FMPA: Increased |

| Lower face height: Increased | |

| Transverse | Facial symmetry: None |

| Soft tissues | Lip competence |

| Upper lip length: 20 mm | |

| Naso-labial angle: Obtuse | |

| Upper incisor show | At rest: 1 mm |

| Smiling: 5 mm | |

| Temporo-mandibular joint | Healthy with good range and co-ordination of movement |

| Intra-oral | |

| Teeth present |  |

| Dental health | Good |

| (restorations, caries) | No restorations or active caries |

| Oral hygiene | Good |

| Occlusion | Incisor relationship: Class III |

| Overjet: Edge to edge | |

| Overbite: Reduced and incomplete | |

| Molar relationship: Class I bilaterally | |

| Canine relationship: 1/2 unit class II bilaterally | |

| Centre lines: Upper to right by 1 mm | |

| Functional occlusion: Group function | |

| Bilateral crossbite tendency with no displacement | |

| Lower arch | Mild crowding |

| Incisor inclination: Retroclined | |

| Curve of Spee: Flat | |

| Upper arch | Severe crowding |

| Incisor inclination: Average | |

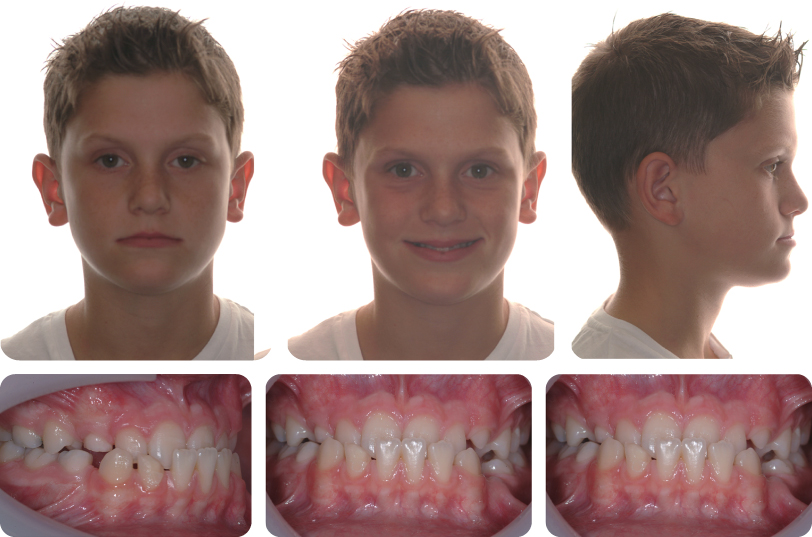

Summary

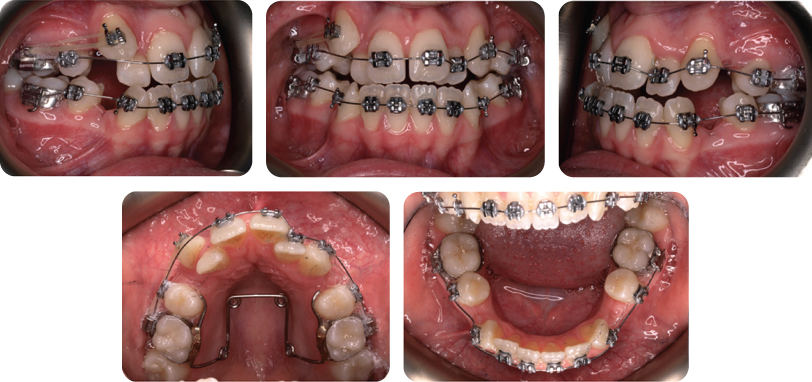

A 13-year-old female presented with a class III malocclusion on a mild skeletal class III pattern with increased vertical dimensions complicated by an edge-to-edge incisor relationship, reduced incomplete overbite and severe crowding in the maxillary arch (Figures 6.12 and 6.13).

What Factors Influence the Decision to Treat a Class III Malocclusion with Orthodontics Alone?

Key factors are the existing skeletal relationship and degree of dento-alveolar compensation. The more severe the skeletal class III relationship, the less likely it is that camouflage treatment will be successful. Similarly, the more retroclined the mandibular incisors and proclined the maxillary incisors, the less likely it is that camouflage will be possible.

Potential future growth is a key factor. In individuals with a class III malocclusion there is a tendency for mandibular growth to persist well beyond adolescent growth (Baccetti et al., 2007; Battagel, 1993). Unlike class II malocclusions, where residual antero-posterior mandibular growth is beneficial and makes orthodontic treatment to camouflage the skeletal discrepancy more likely to be successful, in class III malocclusions supplemental mandibular growth is detrimental and may result in re-establishment of a reverse overjet either during or following treatment. Therefore, it is often better to delay orthodontic treatment (particularly when it involves extractions in the lower arch and retroclination of the lower labial segment) until late adolescence or early adulthood.

What Are the Potential Risks of Orthodontic Camouflage?

The main risks are not being able to achieve a class I incisor relationship in more severe cases, or achieving correction of the incisor relationship only for post-orthodontic change to occur due to continued unfavourable growth. In these cases, if orthognathic surgery becomes necessary, the pre-surgical orthodontics will necessitate decompensation of incisor position, which in the mandibular arch can be difficult to do, particularly if extractions have been carried out, as there is a tendency for space to re-open as the incisors are advanced.

How Is Camouflage Treatment Achieved for a Class III Malocclusion?

Class III camouflage may be achieved with proclination of the maxillary incisors, retroclination of the mandibular incisors or a combination of these movements. Typically, maxillary incisors are already proclined and mandibular incisors are upright, in an attempt to compensate for the skeletal imbalance. The magnitude of movements permissible is governed by aesthetics, function, periodontal health and bone volume.

Which Tooth Movements Are Most Favourable?

Retroclination of the mandibular incisors is usually preferable to excessive maxillary incisor advancement, as significant maxillary incisor proclination may be unaesthetic and may induce non-axial loading, resulting in abnormal mobility (fremitus). However, the amount of lower incisor retroclination may be limited by insufficient alveolar bone labial to the lower incisors and a thin gingival biotype. Excessive retroclination may, therefore, risk dehiscence, root resorption and gingival recession.

What Are the Limits for Orthodontic Treatment of a Class III Malocclusion?

The limits of camouflage treatment are determined by how far the dentition can be moved physically to produce an acceptable result both aesthetically and occlusally. In a class III malocclusion, this involves proclination of the maxillary incisors and retroclination of the mandibular incisors. Retrospective studies have attempted to identify cephalometric indicators of when camouflage treatment is possible, although these are of limited value (Burns et al., 2010; Kerr et al., 1992; Stellzig-Eisenhauer et al., 2002). The limits of tooth movement are defined by the alveolar bone and gingival health. As a general rule, it is unwise to procline the upper incisors beyond 120 degrees to the maxillary plane or retrocline the lower incisors beyond 80 degrees to the mandibular plane.

The criteria for class III cases that can be successfully camouflaged are similar to those for successful interceptive treatment:

- Skeletal class I or mild class III

- Average to low maxilla to mandibular planes angle (MMPA)

- No or minimal existing dento-alveolar compensation

- Edge-to-edge incisor relationship in RCP

- Class I or up to 1/2 unit class III molar relationship in RCP.

In general, camouflage of a class III malocclusion is less successful than camouflage of a class II malocclusion, because even if an acceptable occlusal result can be achieved, retroclination of the lower incisors may increase the relative prominence of the chin and compromise the soft tissue profile further.

Summarize the Principles of Treatment When Camouflaging a Class III Malocclusion

- Avoid extracting in the upper arch or extract as far back as possible in order to support the upper labial segment and allow for advancement of the maxillary incisors.

- Extract further forward in the lower arch to create space for retroclination of the lower incisors and relief of any (usually mild) crowding.

- Mechanics may be facilitated by the extraction of upper second premolars and lower first premolars.

- An alternative in a non-growing patient is extraction of a lower incisor, facilitating retroclination of the remaining incisors.

- Use of class III elastics during treatment will help correct the incisor relationship.

- Placing contra-lateral brackets on the lower canines when using a pre-adjusted edgewise appliance will reverse the angulation in the bracket and encourage retroclination of the mandibular incisors.

- Retroclination of the lower incisors is also promoted by avoiding using a full dimension wire in the lower arch, particularly during space closure.

Summarize the Main Cephalometric Features of the Malocclusion in Figure 6.13

There is maxillary and mandibular retrognathia, a mild skeletal class III pattern and increased vertical proportions. The maxillary incisors are slightly proclined and the mandibular incisors are slightly retroclined.

What Features of this Malocclusion Suggest that Camouflage Treatment Can Be Carried Out?

The antero-posterior skeletal pattern is only mild class III, the existing incisor compensation is not excessive and there is no significant reverse overjet. In addition, the molar relationship is essentially class I bilaterally. One area of concern is the presence of increased vertical proportions and an openbite tendency, which might be difficult to address and correct with stability, particularly as there is a crossbite tendency requiring expansion to correct.

Why Have All the First Premolar Teeth Been Extracted (Figure 6.14)?

First premolars were extracted in the maxillary arch to provide space for the severely crowded upper labial segment. In the mandibular arch, by extracting first premolars in a mildly crowded arch, maximal space is available to retract the lower incisors to correct the incisor relationship and attempt some increase in the overbite.

What Tooth Movements Are Being Achieved in Figure 6.14? What Is the Purpose of the Light Elastic Attached to the UR3?

Incisor alignment is being achieved with light round nickel–titanium archwires and the crossbite is being corrected with a fixed quadhelix appliance. This light elastic is retracting the UR3 into the extraction space, which will provide space to align the palatally crowded UR2.

What Is Happening in Figure 6.15?

The UR3 has been retracted and the UR2 attached to the archwire, and alignment is continuing in the maxillary arch. In the mandibular arch, alignment is at a more advanced stage and there has been some proclination of the lower incisors, which has resulted in a worsening of the reverse overjet.

How Could the Presence of a Reverse Overjet During Alignment Have Been Prevented?

The mandibular canine brackets could have been swapped, eliminating the mesial tip but maintaining the torque. Laceback stainless steel ligatures could have been applied from the first molars to canines, which will also reduce the mesial tip of the canines during alignment. In addition, the lower archwire could have been cinched back behind the first molars to prevent forward movement of the labial segment. However, these latter two interventions are anchorage demanding – encouraging forward movement of the first molars. In this case, as the lower arch is only mildly crowded and most of the space will be used to retract the incisors, these interventions could have been used.

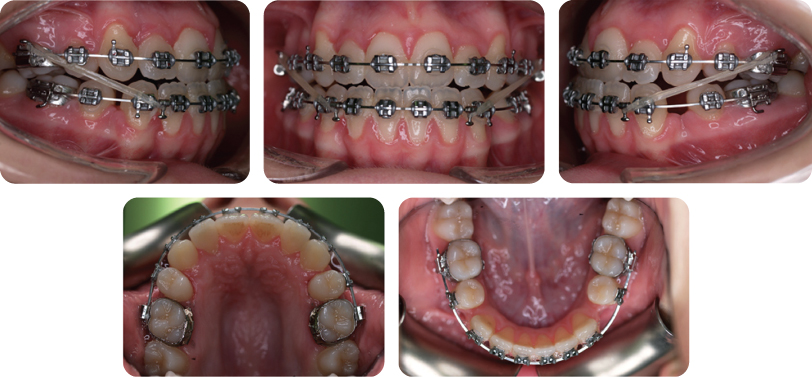

What Mechanics Are Being Used in Figure 6.16?

In both arches alignment is complete. In the maxillary arch, the quadhelix has been removed and all the extraction space has been used during alignment, because of the severe crowding that was present. Both upper lateral incisors are under-torqued at this stage, during alignment from their initial positions on the palatal side, and the crowns are now relatively more labial than the roots because the coronal portion of these teeth moves more effectively than the root. In the mandibular arch, some extraction space is left following alignment, which is essential as this is required to retract the lower labial segment and correct the incisor relationship.

Rigid rectangular stainless steel archwires are present and class III mechanics are being utilized to retract the lower labial segment, close the extraction spaces and procline the upper labial segment.

What Are the Disadvantages of Using Class III Traction in this Case?

The main disadvantage is the associated extrusive force, which will tend to worsen an already reduced overbite.

Figure 6.17 Shows the Final occlusion Following Removal of the Fixed Appliances. Describe the Finish

The overbite is a little tenuous. Any late facial growth with a vertical element might result in further reduction of the overbite, which in this case might lead to development of an open bite. The UL2 crown is slightly distally angulated and both upper lateral incisors could have their incisal edges a little higher in relation to the central incisors.

What Additional Torque Was Required for the Maxillary Lateral Incisors and How Can this Be Achieved?

These teeth required labial root torque. The maxillary incisor brackets can be inverted, which changes the torque prescription from negative to positive. Alternatively, individual torque can be placed on these teeth via third-order bends in the archwire. This can be done on a 19 × 25” stainless steel or titanium–molybdenum alloy archwire (Thickett et al., 2007).

Case 6.5

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses