Candidosis (candidiasis)

INTRODUCTION

Some 50% of the normal population harbour (carry) the fungus Candida albicans as a normal oral commensal mainly on the posterior dorsum of tongue (without any disease) and are therefore termed ‘Candida carriers’. The opportunistic pathogen grows either as yeasts or hyphae (i.e. it is a dimorphic fungus). Actual infection with Candida (usually Candida albicans) is common mainly in people who are otherwise unwell; candidosis is thus called a ‘disease of the diseased’. The importance of Candida has increased greatly, particularly as the HIV pandemic extends since, when host defences are compromised, Candida typically colonizes mucocutaneous surfaces and causes only superficial infections but in immunocompromised people candidosis is commonly oro-pharyngeal and can be a portal for entry into deeper tissues and invasive candidosis (see Chs 53 and 54).

AETIOLOGY

Host defences against Candida species include the following:

Oral epithelium: a physical barrier.

Oral epithelium: a physical barrier.

Microbial interactions: competition and inhibition by the oral flora.

Microbial interactions: competition and inhibition by the oral flora.

Salivary non-immune defences: mechanical cleansing plays a major role but other factors include salivary antimicrobial proteins (AMPs):

Salivary non-immune defences: mechanical cleansing plays a major role but other factors include salivary antimicrobial proteins (AMPs):

lysozyme (muramidase): can damage Candida, stimulate phagocytosis and agglutinate Candida

lysozyme (muramidase): can damage Candida, stimulate phagocytosis and agglutinate Candida

lactoferrin: is antifungal and antibacterial due to binding of iron or altering yeast cell wall permeability

lactoferrin: is antifungal and antibacterial due to binding of iron or altering yeast cell wall permeability

lactoperoxidase: is anticandidal via multiple factors (H2O2 and halides)

lactoperoxidase: is anticandidal via multiple factors (H2O2 and halides)

glycoproteins antigenically similar to blood group antigens – affect adherence to mucosa

glycoproteins antigenically similar to blood group antigens – affect adherence to mucosa

Oral immune defences, which include mainly cell-mediated responses:

Oral immune defences, which include mainly cell-mediated responses:

T cells and phagocytes. The full expression of phagocyte effectiveness is dependent on augmentation by cytokines synthesized or induced by T cells, such as lymphokines and IFN-γ. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) and macrophages phagocytose and produce cytokines, such as: myeloperoxidase, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), nitric oxide and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF).

T cells and phagocytes. The full expression of phagocyte effectiveness is dependent on augmentation by cytokines synthesized or induced by T cells, such as lymphokines and IFN-γ. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) and macrophages phagocytose and produce cytokines, such as: myeloperoxidase, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), nitric oxide and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF).

Salivary sIgA antibodies: which aggregate Candida organisms and/or prevent adherence.

Salivary sIgA antibodies: which aggregate Candida organisms and/or prevent adherence.

PATHOGENESIS

C. albicans can switch frequently and reversibly between several variant, heritable, phenotypes associated with changes in micromorphology, physiology and virulence (‘colony switching’).

C. albicans can switch frequently and reversibly between several variant, heritable, phenotypes associated with changes in micromorphology, physiology and virulence (‘colony switching’).

C. albicans adhere to the oral epithelial surface via extracellular polymeric materials, including mannoprotein and adhesins.

C. albicans adhere to the oral epithelial surface via extracellular polymeric materials, including mannoprotein and adhesins.

Adhesins, such as HWP1 (hyphal wall protein 1), originating from the yeast cell surface, appear important in making hyphal forms adhere more strongly than do yeast forms.

Adhesins, such as HWP1 (hyphal wall protein 1), originating from the yeast cell surface, appear important in making hyphal forms adhere more strongly than do yeast forms.

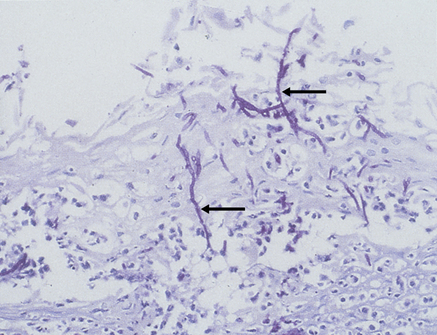

Hyphae invade the superficial epithelium and penetrate, via enzymes such as the phospholipases, lysophospholipases and aspartyl proteinase (secretory aspartyl proteinases; SAP) (Fig. 39.1) as far as the stratum spinosum.

Hyphae invade the superficial epithelium and penetrate, via enzymes such as the phospholipases, lysophospholipases and aspartyl proteinase (secretory aspartyl proteinases; SAP) (Fig. 39.1) as far as the stratum spinosum.

Epithelial endocytic pathways are key innate immune mechanisms in host defence. Defective endolysosomal maturation may partially explain the inability of oral epithelial cells to kill C. albicans.

Epithelial endocytic pathways are key innate immune mechanisms in host defence. Defective endolysosomal maturation may partially explain the inability of oral epithelial cells to kill C. albicans.

C. albicans invades oral epithelial cells by inducing its own endocytosis by the adhesin and invasin Als3 and gains access to epithelial vacuolar compartments. C. albicans is internalized by oral epithelial cells through actin-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis and is taken into vacuolar compartments immediately following its internalization. Candida-containing endosomes transiently acquire early endosomal marker EEA1, but show marked defects in acquisition of late endosomal marker LAMP1 and lysosomal marker cathepsin D.

C. albicans invades oral epithelial cells by inducing its own endocytosis by the adhesin and invasin Als3 and gains access to epithelial vacuolar compartments. C. albicans is internalized by oral epithelial cells through actin-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis and is taken into vacuolar compartments immediately following its internalization. Candida-containing endosomes transiently acquire early endosomal marker EEA1, but show marked defects in acquisition of late endosomal marker LAMP1 and lysosomal marker cathepsin D.

The innate immune system is a first-line defence and involves pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors and C-type lectin-receptors that not only induce innate immune responses but also modulate cellular and humoral adaptive immunity.

The innate immune system is a first-line defence and involves pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors and C-type lectin-receptors that not only induce innate immune responses but also modulate cellular and humoral adaptive immunity.

IL-12: a cytokine family which includes IL-12, IL-23, IL-27, and IL-35 – links to both innate and adaptive immunity systems. An essential component of the response that leads to the generation of Th1-type cytokine responses and protection activity against disseminated candidosis.

IL-12: a cytokine family which includes IL-12, IL-23, IL-27, and IL-35 – links to both innate and adaptive immunity systems. An essential component of the response that leads to the generation of Th1-type cytokine responses and protection activity against disseminated candidosis.

CD4 T-cells are crucial in the regulation of immunity and inflammation; Th1/2, helper cells, together with Th17 and Treg cells are important.

CD4 T-cells are crucial in the regulation of immunity and inflammation; Th1/2, helper cells, together with Th17 and Treg cells are important.

Th17 and release IL-17 (which recruits neutrophils), IL-21 (which stimulates CD8 or NK cells) and IL-22, the latter stimulating epithelial cells to produce proteins with antimicrobial activity against Candida.

Th17 and release IL-17 (which recruits neutrophils), IL-21 (which stimulates CD8 or NK cells) and IL-22, the latter stimulating epithelial cells to produce proteins with antimicrobial activity against Candida.

Fungal pattern-recognition receptors such as C-type lectin receptors trigger protective Th17 responses which play the predominant role against mucosal candidiasis. IL-17A and IL-17 F are essential for mucocutaneous immunity against C. albicans

Fungal pattern-recognition receptors such as C-type lectin receptors trigger protective Th17 responses which play the predominant role against mucosal candidiasis. IL-17A and IL-17 F are essential for mucocutaneous immunity against C. albicans

Dectin-1, a C-type lectin that recognizes 1,3-beta-glucans from fungi, including Candida, is involved in the initiation of the immune response against fungi. Patients bearing the Y238X polymorphism in the DECTIN-1 gene are more likely to be colonized with Candida species, compared with patients bearing wild-type DECTIN-1.

Dectin-1, a C-type lectin that recognizes 1,3-beta-glucans from fungi, including Candida, is involved in the initiation of the immune response against fungi. Patients bearing the Y238X polymorphism in the DECTIN-1 gene are more likely to be colonized with Candida species, compared with patients bearing wild-type DECTIN-1.

Oral epithelial cells orchestrate an innate response to C. albicans via NF-κB and a biphasic MAPK response.

Oral epithelial cells orchestrate an innate response to C. albicans via NF-κB and a biphasic MAPK response.

Activation of NF-κB and the first MAPK response, constituting c-Jun activation, is due to fungal cell wall recognition while the second MAPK phase, constituting MKP1 and c-Fos activation, depends upon hypha formation and fungal burdens – and correlates with the pro-inflammatory responses.

Activation of NF-κB and the first MAPK response, constituting c-Jun activation, is due to fungal cell wall recognition while the second MAPK phase, constituting MKP1 and c-Fos activation, depends upon hypha formation and fungal burdens – and correlates with the pro-inflammatory responses.

Activation of the kallikrein–kinin system and other factors result in an inflammatory response in the connective tissue comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells and other leukocytes.

Activation of the kallikrein–kinin system and other factors result in an inflammatory response in the connective tissue comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells and other leukocytes.

PMNL migrate into the epithelium in defensive mode, but candidal cell-wall mannans and glycans may impair PMNL chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst, T lymphocyte reactivity and the macrophage secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF).

PMNL migrate into the epithelium in defensive mode, but candidal cell-wall mannans and glycans may impair PMNL chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst, T lymphocyte reactivity and the macrophage secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF).

Defective cell-mediated immune responses are commonly associated with mucocutaneous Candida infections.

Defective cell-mediated immune responses are commonly associated with mucocutaneous Candida infections.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Candidosis (candidiasis; moniliasis) is the state when Candida species cause lesions or symptoms:

The most dominant oral Candida species, in decreasing order of frequency, are:

The most dominant oral Candida species, in decreasing order of frequency, are:

C. albicans is the only common cause of oral fungal or yeast infection. C. albicans can be differentiated serologically into A and B serotypes, equally distributed in healthy individuals, but there is a significant shift to type B in immunocompromised patients.

C. albicans is the only common cause of oral fungal or yeast infection. C. albicans can be differentiated serologically into A and B serotypes, equally distributed in healthy individuals, but there is a significant shift to type B in immunocompromised patients.

Species other than C. albicans (especially C. krusei) are increasingly seen, especially in persons with compromised immunity. In HIV disease, for example, C. dubliniensis and C. geotrichium may appear.

Species other than C. albicans (especially C. krusei) are increasingly seen, especially in persons with compromised immunity. In HIV disease, for example, C. dubliniensis and C. geotrichium may appear.

Antifungal resistance is an increasingly serious clinical reality.

Antifungal resistance is an increasingly serious clinical reality.

Symptomatic oral candidosis presents as mainly:

white lesions, in which hyphal forms are common: these include thrush, candidal leukoplakia and chronic mucocutaneous candidosis

white lesions, in which hyphal forms are common: these include thrush, candidal leukoplakia and chronic mucocutaneous candidosis

red lesions, in which yeast forms predominate: these include denture-related stomatitis, median rhomboid glossitis, and erythematous candidosis. These may be symptomless, although antibiotic stomatitis and angular cheilitis in particular can cause soreness.

red lesions, in which yeast forms predominate: these include denture-related stomatitis, median rhomboid glossitis, and erythematous candidosis. These may be symptomless, although antibiotic stomatitis and angular cheilitis in particular can cause soreness.

Factors that can increase the liability to oral candidosis are shown in Box 39.1. Candidosis may also affect or spread from or to the mouth, from:

pharynx, oesophagus, and rarely lungs, liver or elsewhere

pharynx, oesophagus, and rarely lungs, liver or elsewhere

anogenital region: candidosis can also be sexually shared (e.g. by vaginal, oral or anal sex)

anogenital region: candidosis can also be sexually shared (e.g. by vaginal, oral or anal sex)

By tradition, the most frequently adopted classification of oral candidosis has been into (Box 39.2):

pseudomembranous candidosis (thrush)

pseudomembranous candidosis (thrush)

hyperplastic candidosis, which was further subdivided into four groups based on localization patterns and endocrine involvement as follows: chronic oral candidosis (Candida leukoplakia); candidosis endocrinopathy syndrome; chronic localized mucocutaneous candidosis; and chronic diffuse candidosis.

hyperplastic candidosis, which was further subdivided into four groups based on localization patterns and endocrine involvement as follows: chronic oral candidosis (Candida leukoplakia); candidosis endocrinopathy syndrome; chronic localized mucocutaneous candidosis; and chronic diffuse candidosis.

DIAGNOSIS OF CANDIDOSIS

Diagnosis can, if necessary, be supported by:

identification of blastospores and pseudohyphae in stained smears from a lesion

identification of blastospores and pseudohyphae in stained smears from a lesion

culture, usually on Sabouraud or dextrose Sabouraud medium

culture, usually on Sabouraud or dextrose Sabouraud medium

PCR studies – mainly for detection of invasive candidosis

PCR studies – mainly for detection of invasive candidosis

occasionally by histology stained by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS).

occasionally by histology stained by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS).

up to about 50% of the population are carriers

up to about 50% of the population are carriers

any attempt at quantitation of Candida is affected by time of sampling and the way in which the specimen is handled.

any attempt at quantitation of Candida is affected by time of sampling and the way in which the specimen is handled.

Tests of immune function are indicated mainly in HIV disease or chronic mucocutaneous candidosis.

Since some endocrine disorders may be associated with chronic mucocutaneous candidosis, tests of thyroid, parathyroid and adrenocortical function are warranted in selected individuals (Table 39.1).

Table 39.1

Aids that might be helpful in diagnosis/prognosis/management in some patients suspected of having candidosis (candidiasis)*

| In most cases | In some cases |

| Culture and sensitivity Full blood picture |

Biopsy Serum ferritin, vitamin B12 and corrected whole blood folate levels ESR CD4 counts Serology for antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies Plasma cortisol Plasma calcium and phosphate levels |

TREATMENT OF CANDIDOSIS (see also Chs 4 and 5)

Few patients have spontaneous remission unless the condition is solely related to, for example, the use of an antimicrobial, or a topical corticosteroid, and thus, in other cases, treatment is often indicated (Table 39.2). Often, in the treatment of fungal infections, attention to the underlying cause will avoid the need for prolonged or repeated courses of treatment. Intermittent or prolonged topical antifungal treatment may be necessary where the underlying cause is unavoidable or incurable. Treatment includes the following measures:

Table 39.2

Regimens that might be helpful in management of patient suspected of having candidosis

| Regimen | Use in primary or secondary care |

| Beneficial | Nystatin Miconazole Fluconazole Itraconazole |

| Unproven effectiveness | Chlorhexidine Ciclopirox Genti/> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses