chapter 37 The Medically Compromised Patient

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular disease ranks as the number one cause of death in the United States, United Kingdom, and other industrialized nations. It is estimated that the number of persons in the United States with signs and symptoms of cardiovascular disease exceeds 80.7 million. In 2005, 869,724 persons died from cardiovascular disease in the United States. Cancer, the second leading cause, was responsible for 553,888 deaths.1

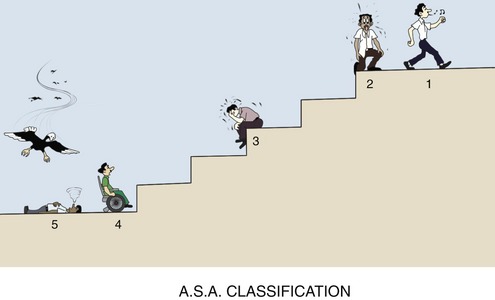

Patients at cardiovascular risk are usually able to tolerate elective and emergency dental care. Modifications in the planned dental treatment are based on the severity (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] 2, 3, or 4) of the disease process as determined through physical evaluation of the patient (see Chapter 4). Sedation and pain control are of much greater importance in these patients than in ASA 1 patients. Specific details relating to the management of cardiovascular-risk patients are discussed in the following section.

Angina Pectoris

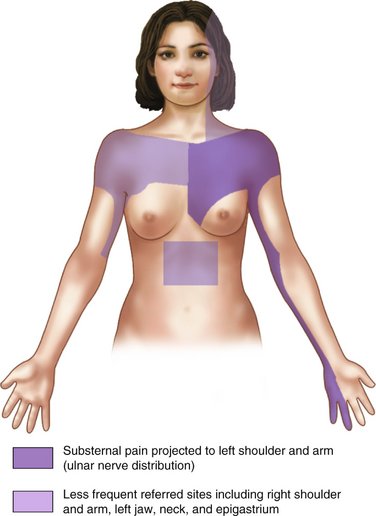

Angina pectoris is usually a result of arteriosclerotic heart disease, but may occasionally occur in the absence of significant disease through coronary artery spasm, severe aortic stenosis, or aortic insufficiency. The basic mechanism involved in angina pectoris is a discrepancy between myocardial O2 demand and O2 delivery through the coronary arteries. Anginal pain is described as a squeezing or pressurelike pain, retrosternal or slightly to the left of the sternum, that appears suddenly during exertion and may radiate in a set pattern (Figure 37-1); it typically resolves with rest or the administration of nitrates. Patients with angina may be taking long-acting nitrates, such as isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil, Sorbitrate), to prevent the occurrence of acute episodes. Nitroglycerin is available for administration in several forms, including an intravenous (IV) form, translingual spray (Nitrolingual), transmucosal tablet, oral sustained-release form, topical ointment, transdermal patch, and the traditional sublingual tablet.2

Factors increasing the likelihood of an acute exacerbation of anginal pain include the following:

Myocardial Infarction

More than 1.39 million Americans suffer acute MI annually.1 In 2004, ischemic heart disease and acute MI were responsible for 607,000 deaths in the United States.3 Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, responsible for 20% of all deaths occurring in the United States in 2004.3

Patients who have suffered an acute MI and survived represent a definite risk during dental and surgical treatment. Immediately after an MI, the incidence of reinfarction is high (36% reinfarction rate on surgical patients within 3 months of first MI).4,5 With time and the formation of a myocardial scar, the incidence of reinfarction declines. Reinfarction rates fall to 16% at 5 months for post-MI patients undergoing surgical procedures and to 5% at 6 months after infarction. Reinfarction rates then level off at 5% and remain at that level indefinitely. By comparison, the risk of infarction during surgical procedures for a patient who has not had an MI is less than 0.1%.

An acute MI may be precipitated when the patient undergoes unusual stress, whether physical (pain) or emotional (anxiety). Unfortunately, the patient need not be undergoing any physical activity at the time of onset of the MI. Alpert and Braunwald reported that 51% of patients were at rest and 8% were asleep when the signs and symptoms of MI initially developed.6 Of the patients, 18% were performing moderate or usual exertion, whereas only 13% were physically exerting themselves. It therefore appears to be more a matter of (bad) timing than a result of dental treatment when an acute MI develops in the dental office. Stress, however, does increase the risk to the patient who has had an MI and must be considered.

Oral sedation is recommended for minimal levels (see Chapter 7). More profound (deep) sedation increases the risk of hypotension and respiratory depression with hypoxia. In the event that this does occur, airway management with supplemental O2 administration is essential. IM sedation is not recommended unless other techniques are unavailable or ineffective, and then only minimal to moderate sedation is indicated, with the administration of O2 via nasal cannula or nasal hood encouraged.

Inhalation sedation is highly recommended. N2O-O2 inhalation sedation provides the myocardium with additional O2 throughout the procedure. N2O-O2 has been used by paramedical and medical personnel for pain management during acute MI and has proven valuable in decreasing or eliminating the pain of MI.7

High Blood Pressure

Elevated blood pressure is not uncommon within the dental office because the stress associated with treatment leads to increased catecholamine release and subsequent elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. In Chapter 4, ASA classifications for blood pressure were presented. The two categories that must be reviewed are ASA 3 and 4. ASA 3 patients have a blood pressure of 160 to 199 mm Hg systolic and/or 95 to 115 mm Hg diastolic. ASA 3 patients may receive elective dental care; however, steps should be taken to prevent any further elevation of blood pressure. Two of the most important steps are the management of pain through the effective use of local anesthesia (vasopressors are not contraindicated in the hypertensive ASA 3 patient) and the management of fear and anxiety. Hypertensive ASA 4 patients have a systolic blood pressure above 200 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure in excess of 115 mm Hg. Elective dental care is postponed until the blood pressure is better controlled. Emergency procedures may be performed; however, sedation and effective pain control are absolutely mandatory to prevent any further elevation in blood pressure. Hospitalization of the ASA 4 patient who requires emergency dental care should receive serious consideration.

Further elevation of the hypertensive patient’s blood pressure may lead to a number of acute cardiovascular crises, including cerebrovascular accident (CVA, stroke, “brain attack”), acute MI, acute renal failure, and acute HF (pulmonary edema). Most patients with high blood pressure are taking antihypertensive drug therapy to lower their blood pressure. Many drugs, each of which has its own side effects, are used to manage high blood pressure. The dentist must be aware of these side effects and any possible drug-drug interactions and take steps to minimize their occurrence or at least be able to manage them successfully. Table 37-1 lists the major categories of antihypertensive drugs and their more common side effects.

Table 37-1 Side Effects and Drug Interactions of Antihypertensive Medications

| Drug | Major Side Effects | Drug Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | Hypotension | |

| Reversible renal insufficiency | ||

| Reversible hyperkalemia | ||

| Clonidine | Drowsiness | |

| Orthostatic hypotension | ||

| Xerostomia | ||

| Guanethidine | Orthostatic hypotension | Alcohol increases orthostatic hypotension |

| Hydralazine | Tachycardia | |

| Palpitation | ||

| Increased angina | ||

| Increased CHF | ||

| Loop diuretics | Hypokalemia | |

| αα-Methyldopa | Orthostatic hypotension | |

| Drowsiness | ||

| Depression | ||

| Xerostomia | ||

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | Hyperkalemia | |

| Nausea (triamterene) | ||

| Prazosin | Orthostatic hypotension with syncope | |

| Dizziness | ||

| Weakness | ||

| Blurred vision | ||

| Nausea | ||

| Headache | ||

| Palpitation | ||

| Propranolol | Bradycardia CHF Increased asthmaWeaknessDepression |

Epinephrine may induce bradycardia |

| Reserpine | Drowsiness Sedation Weakness Depression Bradycardia |

Hypotension with general anesthesia |

| Thiazide diuretics | GI upset | |

| Weakness | ||

| Hypokalemia | ||

| Hyperglycemia |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; CHF, congestive heart failure; GI, gastrointestinal.

Dysrhythmias

Patients with clinically significant dysrhythmias will be receiving antidysrhythmic drugs. These drugs include quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide, flecainide, propafenone, sotalol, and many others.8

Local anesthesia is recommended for intraoperative and postoperative pain management. The use of vasopressor-containing local anesthetics is not contraindicated in most ASA 2 and 3 patients. Epinephrine-impregnated gingival retraction cord should be avoided in these patients. Box 37-1 lists contraindications (absolute and relative) to the inclusion of vasopressors in local anesthetic solutions.

Heart Failure

An estimated 4.8 million Americans have HF with an estimated 400,000 new cases occurring each year. The incidence of HF is equally frequent in men and women, and annual incidence approaches 10 per 1000 population after 65 years of age. Incidence is twice as common in persons with hypertension compared with normotensive persons and five times greater in persons who have had a myocardial infarction compared with persons who have not. High blood pressure is a common precursor, with more than 75% of patients with CHF having a history of preexisting high blood pressure.9

There is considerable variation in the severity of HF. A commonly used method of classification of HF is called the functional reserve category. Four classes are recognized, based on a patient’s ability to climb a normal flight of stairs (Figure 37-2). The functional reserve classification is defined as follows:

These numbers can be considered the ASA physical status classification for HF.

Congenital Heart Disease

The incidence of congenital heart disease is 9 per 1000 live births. Some defects develop as a result of genetic abnormalities; however, most congenital heart lesions occur in the absence of any detectable chromosomal abnormality. Although there are a large number of congenital lesions, those listed in Box 37-2 account for more than 80% of those seen in children with congenital heart disease. Ventricular septal defects account for approximately one third of all lesions, and atrial septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus account for 10% each; other relatively common defects include pulmonary stenosis and coarctation of the aorta. Less common are tetralogy of Fallot, aortic stenosis, and transposition of the great arteries.

Box 37-2

Congenital Heart Lesions

Primary concerns associated with dental management of this patient include the exacerbation of HF and cardiac dysrhythmias secondary to the stresses associated with dental treatment and the possibility of infection producing bacterial endocarditis. Consulting the most recent American Heart Association (AHA), American Medical Association (AMA), and American Dental Association (ADA) guidelines for prophylaxis along with possible medical consultation with the patient’s primary care physician will aid in determining the need for prophylactic antibiotics.10 In many patients with surgically repaired defects, the need for antibiotic coverage during dental care exists for life.

Valvular Heart Disease

Valvular heart disease is a possible sequela of rheumatic fever. The incidence of valvular heart disease secondary to rheumatic fever has diminished over the past 4 decades; however, congenital valvular lesions are diagnosed with increasing regularity. It is estimated that more than 18,000 cardiac valvular replacements are performed annually in the United States.11

Life expectancy is prolonged for most patients receiving valvular replacements. Along with this benefit, however, is the ever-present prospect of bacterial endocarditis. The reader is referred to the guidelines for prophylaxis, which present detailed antibiotic regimens for these patients.10 The patient’s primary care physician may be consulted before dental treatment.

RENAL DISEASE

An estimated 20 million adults in the United States have chronic kidney disease (CKD)—about one in nine adults.12 Glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis, nephrotic syndrome, chronic renal insufficiency, and chronic renal failure are the most common disorders of renal function. Renal dialysis and transplantation are used in the management of chronic renal failure. In 2006 it was estimated that more than 200,000 persons were undergoing dialysis for end-stage renal disease.12 In 2006, 17,092 patients received renal transplants in the United States. There were more than 95,000 patients awaiting kidney transplant as of April 2007. In 2006, 3916 kidney patients died while awaiting their kidney transplant.12

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses