Cleft–Orthognathic Surgery

The Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Deformity

• Facial Growth Implications of Cleft Palate Repair in the Infant with Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Deformity

• Timing of Orthognathic Surgery

• Residual Deformities in the Adolescent with Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate

• Orthodontic Considerations in the Patient with Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate with Jaw Deformity

• Immediate Presurgical Assessment

• Orthognathic Approach for Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Deformities

• Clinical Management after Initial Surgical Healing

• Orthognathic Surgery for Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: Review of Study

Facial Growth Implications of Cleft Palate Repair in the Infant with Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Deformity

Ross confirmed that individuals who are born with cleft lip and palate have intrinsic deficiencies in the midfacial skeleton that are made significantly worse by operations.118 Mulliken and colleagues from Boston Children’s Hospital found that 76.5% of teenagers with repaired bilateral cleft lip palate (BCLP) required maxillary advancement.43 They showed that the need for orthognathic surgery is dependent on the severity of the cleft type as well as the number and extent of previous operative procedures. Results from The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, showed that 65.1% of their patients with BCLP required or underwent orthognathic surgery, whereas 70% of children with BCLP who were referred to their team some time after cleft lip repair were found to require orthognathic surgery.23 David and colleagues from the cleft craniofacial unit in Adelaide, Australia, followed a consecutive group of patients with BCLP from birth to maturity and determined the need for orthognathic surgery.24 Each patient was followed according to treatment protocol and then at 18 years of age assessed for dentofacial deformity. A skeletal Class III malocclusion that required orthognathic correction was present in 17 of the 19 patients (89.5%), whereas the remaining 2 patients were found to have a malocclusion that was manageable with orthodontics alone. Fourteen underwent orthognathic surgery, and the remaining three declined the offer for correction.

Saperstein and colleagues discussed facial growth in children with complete clefting of the primary palate (i.e., the lip through the incisal foramen) but with an intact secondary palate (i.e., the incisal foramen through the uvula).120 This was a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of non-syndromal patients with bilateral complete clefting of the primary palate (n = 7) as compared with those with bilateral complete clefting of both the primary and secondary palates (n = 27). Angular and linear measurements of the midfacial region were made on lateral cephalograms. The research documented that individuals with a bilateral cleft of the primary palate who underwent lip repair during infancy most frequently have a normal or even slightly forward maxillary position as compared with age-matched controls. This was in contrast with children with a bilateral cleft of both the primary and secondary palates who underwent lip repair followed by palate repair before they were 1 year old, who demonstrated a high incidence of maxillary deficiency. The study clarified that cleft palate repair carried out before the patient is 1 year old—and not the cleft lip repair itself—is responsible for the high incidence of midface hypoplasia.

Coordinated Team Approach

The care of the patient with BCLP is best delivered by an integrated group of dental and medical specialists who evaluate and then provide coordinated definitive treatment.8,77,92 It is no longer acceptable for individual surgeons, orthodontists, restorative dentists, speech pathologists, and otolaryngologists to carry out extended treatment without considering all aspects of the patient’s care and communicating effectively with the patient, the family, and the collaborating clinicians. The Eurocleft study found no association between high-intensity treatments and favorable results. In other words, the more operations and years of orthodontic appliances (i.e., heavy burden of care), the worse the outcome.79

Treatment Protocol

The orthodontist provides interceptive treatment during the mixed dentition in coordination with bone grafting; and carries out definitive orthodontics in conjunction with orthognathic surgery, when indicated. From the mixed-dentition phase, the orthodontist should recognize the patient with BCLP who will likely be in need of orthognathic surgery.20,21,25,36,52,53,64,80,90,114,117,121,132,145 Instituting extensive camouflage (dental compensatory) treatment is likely to jeopardize periodontal health and lead to late dental relapse of the occlusion. Proceeding with a compromised orthodontic (camouflage) approach should only be entered into with full disclosure to the family and other treating clinicians.

Before orthognathic surgery, a speech pathologist performs an evaluation to characterize VP function and to identify articulation errors that result from the cleft palate, the jaw deformity, and the dental malocclusion (see Chapter 8). Such evaluation is important, because VP function may deteriorate after maxillary advancement. A nasoendoscopic guided speech assessment is preferred to obtain maximum objective data. VP closure that is adequate before surgery may become borderline afterward, and VP closure that is borderline may become inadequate. The successful orthodontic, surgical, and dental correction of crossbites, open bite, cleft–dental gaps, negative overjet, and residual oronasal fistula represents the most effective way to correct the identified articulation distortions (see Chapter 8).

A thorough evaluation of the upper airway is conducted to assess for any areas of obstruction (see Chapter 10). A formal sleep study (polysomnogram) is completed if there is a suspicion of obstructive sleep apnea (see Chapter 26). If indicated, simultaneous intranasal procedures to open the airway should be carried out at the time of orthognathic surgery (see Chapters 10 and 15).

Timing of Orthognathic Surgery

Correction of the cleft jaw deformity is best carried out with a consideration of skeletal maturity and before the patient finishes high school.66,69 Maxillofacial growth is generally complete between the ages of 14 and 16 years in girls and the ages of 16 and 18 years in boys. However, skeletal growth is variable, and it may be further clarified by an analysis of sequential cephalometric radiographs taken at intervals (see Chapter 17). Patient and family preferences for the timing of reconstruction on the basis of the patient’s psychosocial and functional needs (i.e., speech, swallowing, chewing, and breathing) should also be taken into account.

As early as 1986, investigators showed that, if Le Fort I advancement is completed during the mixed dentition in a patient with a cleft palate, then another orthognathic procedure will be necessary after skeletal maturity is reached.140–143 All research to date indicates that a Le Fort I osteotomy carried out at an early age, with the use of either standard or distraction osteogenesis (DO) techniques, results in no further horizontal maxillary growth.16,34,35,46,48,59,95

Residual Deformities in the Adolescent with Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate

The adolescent patient with BCLP often has several residual deformities that can be challenging to manage. The central deformity is maxillary hypoplasia, which is often combined with residual oronasal fistula, bone defects, intranasal obstruction, soft-tissue scarring, and occasionally VP dysfunction (Figs. 33-1 through 33-17). In addition, the maxillary lateral incisors are usually congenitally absent or hypoplastic (93% of the time), and the patients often have cleft–dental gaps.13 Secondary deformities of the nose, the mandible, and the chin region are also common. The prevalence of these residual deformities in mature patients with BCLP varies widely, depending on the treating clinician’s philosophy, available expertise, the individual’s intrinsic biologic growth potential, and patient and family interests. Published clinical surveys indicate that, despite a cleft team’s best efforts, a significant number of children with BCLP will not make themselves available for mixed-dentition grafting (i.e., before the eruption of the maxillary canines).33,137 In addition, a percentage of those who do will undergo unsuccessful grafting procedures and require other means of reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. For all of these reasons, a subgroup of individuals with BCLP continues to present at or after adolescence with multiple cleft-related challenges that may include the following:

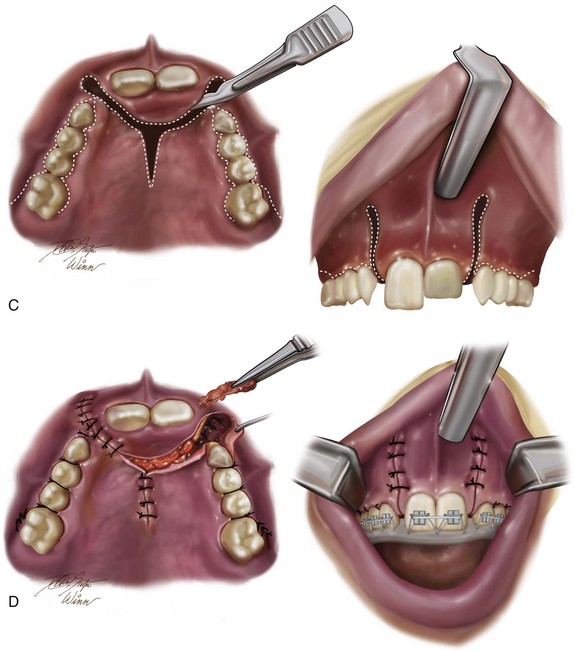

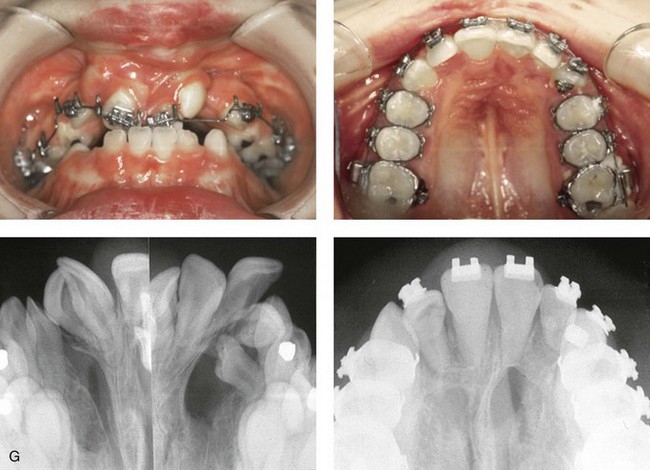

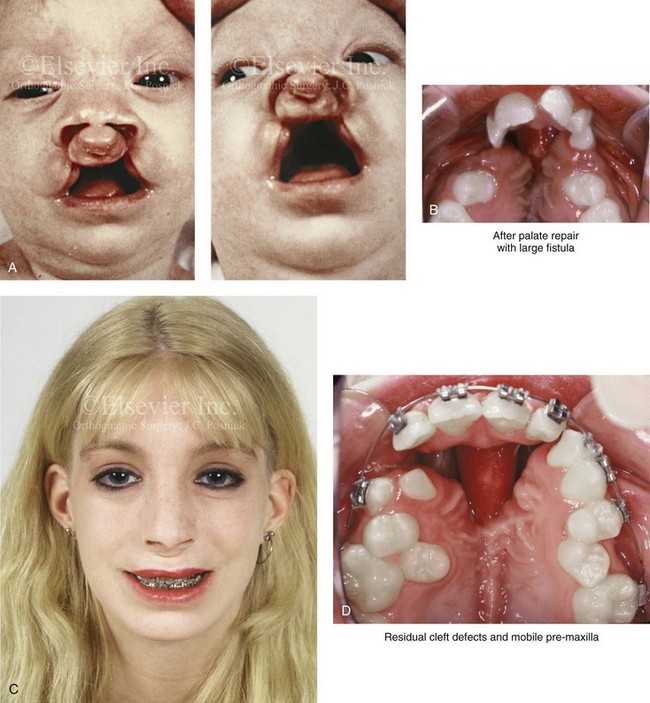

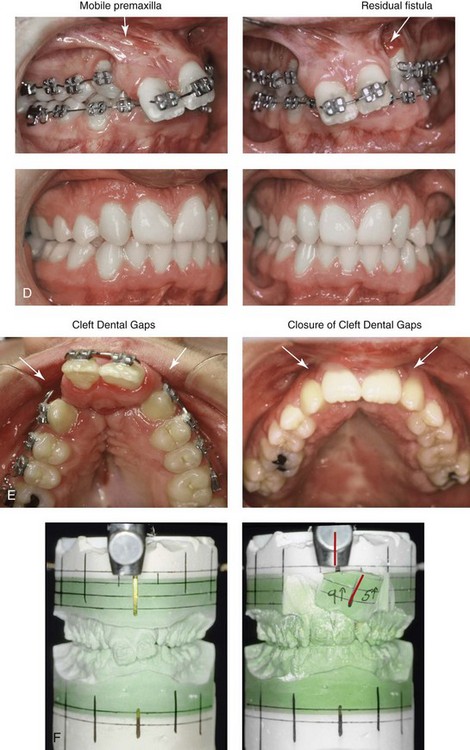

Figure 33-1 A child who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent lip and palate repair during early childhood. During the mixed dentition, she presented to this surgeon with a mobile premaxilla, alveolar and palatal defects, and residual (bilateral) labial and palatal fistulas. She then underwent a short phase of orthodontic treatment to expand the maxillary arch width. This was followed by iliac grafting of the skeletal defects and fistula closure. She was fortunate to have adequately developed lateral incisors. A, Facial views during infancy and early childhood. B, Facial and occlusal views during the mixed dentition with interceptive orthodontic treatment in progress and before bone grafting. C, Illustration of incisions for the elevation of flaps, fistula closure, and grafting during the mixed dentition in a child with BCLP. Maintenance of the labial mucosa to the premaxilla is essential. D, Illustration of flap and wound closure after grafting for fistula closure. The occlusal splint is secured to the maxillary segments to immobilize the premaxilla during initial bone healing. Parts C, D are modified from an original illustration by Bill Winn. E, Frontal and occlusal views at 14 years of age after successful grafting, fistula closure, and stabilization of the premaxilla, with definitive orthodontic alignment in progress. F, Views of the healed skin incision used to harvest the iliac graft. G, Palatal and radiographic views before and after successful bone grafting and orthodontic alignment.

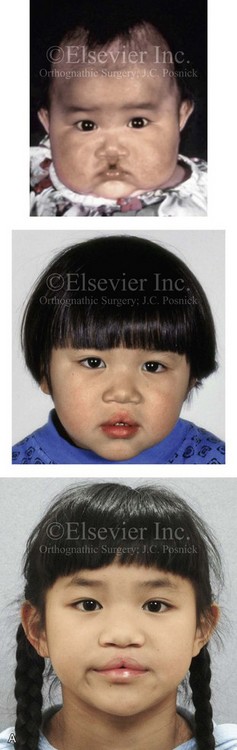

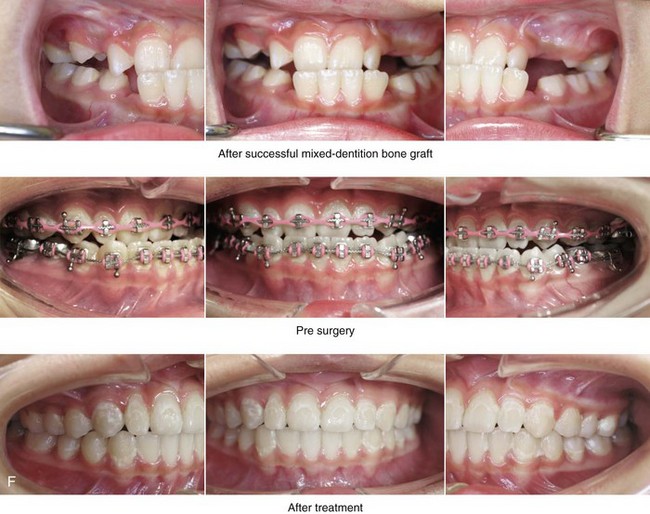

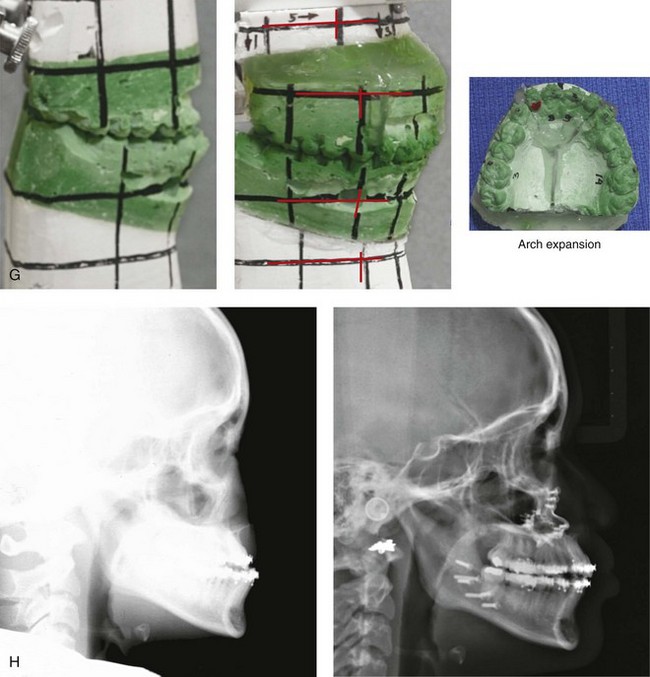

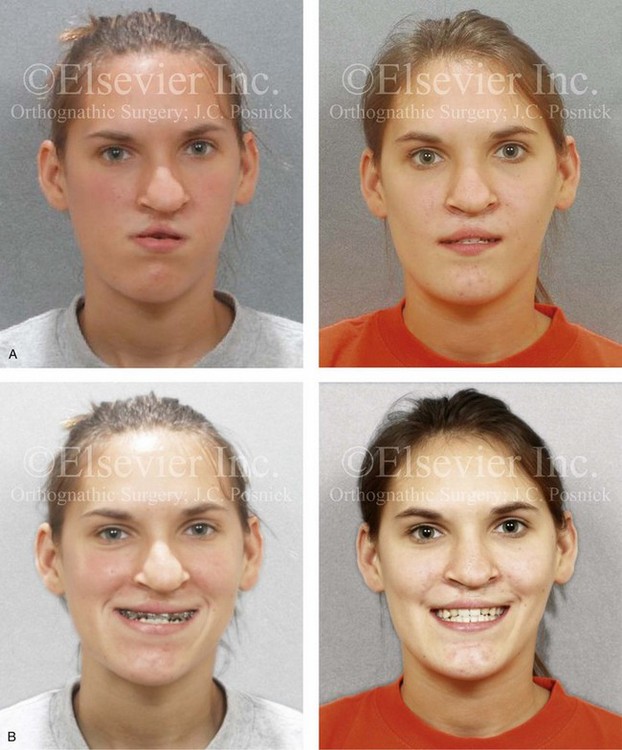

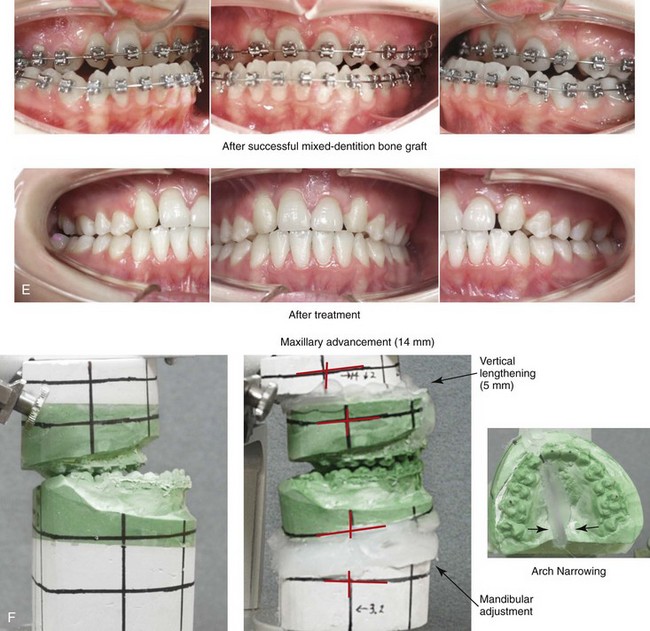

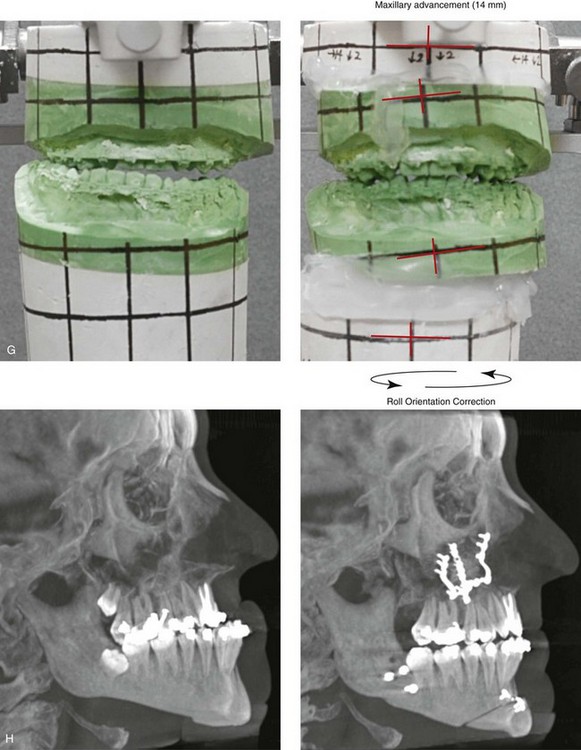

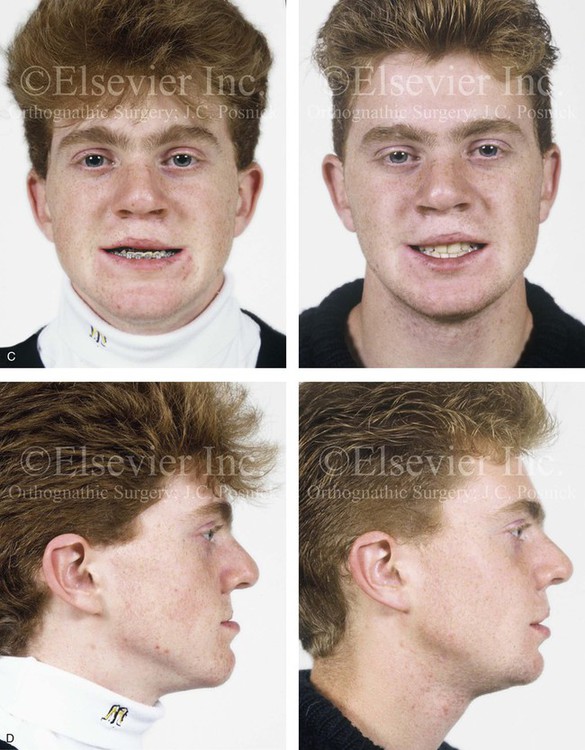

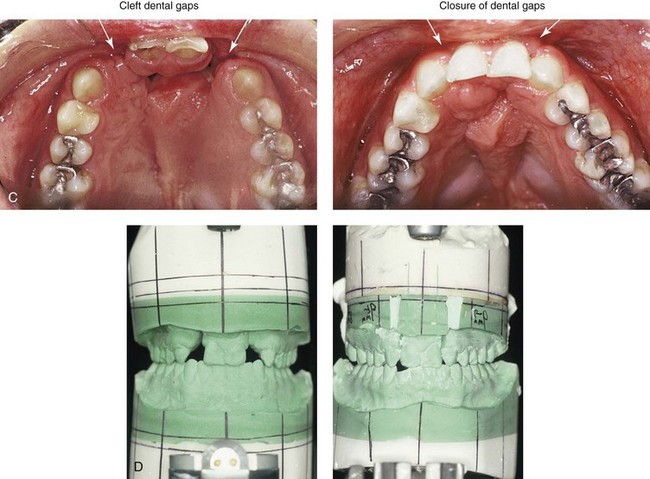

Figure 33-2 A child who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate and who had intact nasal sills. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent lip and palate repair during infancy. During the mixed dentition, she underwent successful bone grafting with stabilization of the premaxilla. The canines erupted through the grafted cleft sites and established a normal alveolar ridge. The lateral incisors were essentially normal and maintained within the arch form. With significant maxillary hypoplasia, the patient underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic approach. Her procedures included Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments (correction of arch width and curve of Spee, horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (clockwise rotation); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal facial views before lip repair, after primary lip and palate repair, and at 8 years of age just before mixed dentition grafting. B, Frontal views in repose as a teenager before and after reconstruction. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. E, Profile views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views during the mixed dentition, with orthodontics in progress before orthognathic surgery, and then after the completion of treatment. G, Articulated dental casts indicate analytic model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

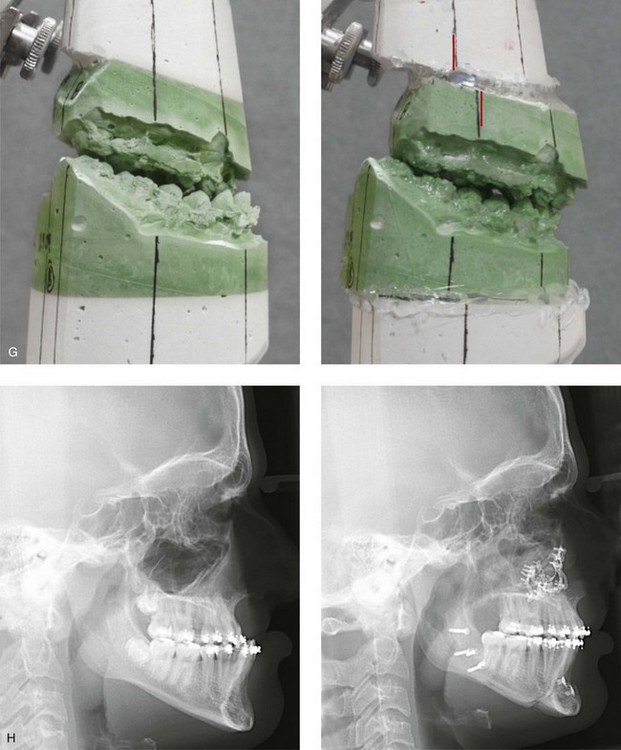

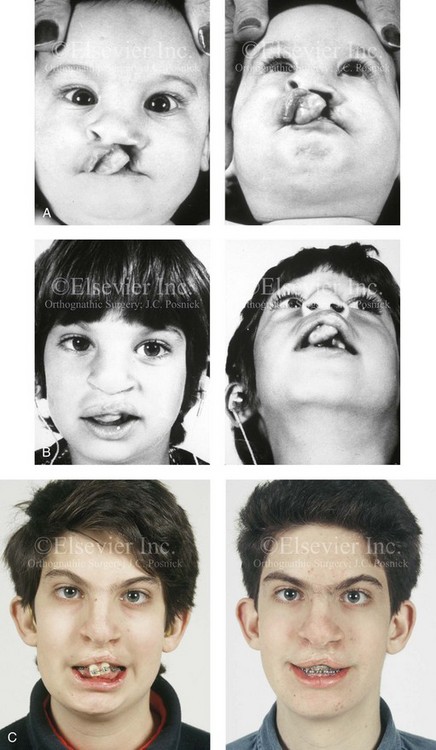

Figure 33-3 A child who was born with van der Woude syndrome that included bilateral cleft lip and palate and lower lip pits. He was referred to this surgeon and underwent lip and palate repair as well as lower lip pit excisions during childhood. He underwent successful mixed-dentition grafting and fistula closure. As a teenager, he demonstrated maxillary hypoplasia with secondary deformities of the mandible and the nasal cavity. He then underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic/intranasal surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included standard Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical lengthening, horizontal advancement, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, The patient is shown at the time of birth and then just before mixed-dentition grafting. B, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. E, Profile views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views are shown before mixed-dentition bone grafting and fistula closure, with orthodontics in preparation for orthognathic surgery, and after the completion of reconstruction. A dental implant is planned for the congenitally missing right maxillary bicuspid when the patient is 18 years old. G, Articulated dental casts indicate analytic model planning. H, Cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

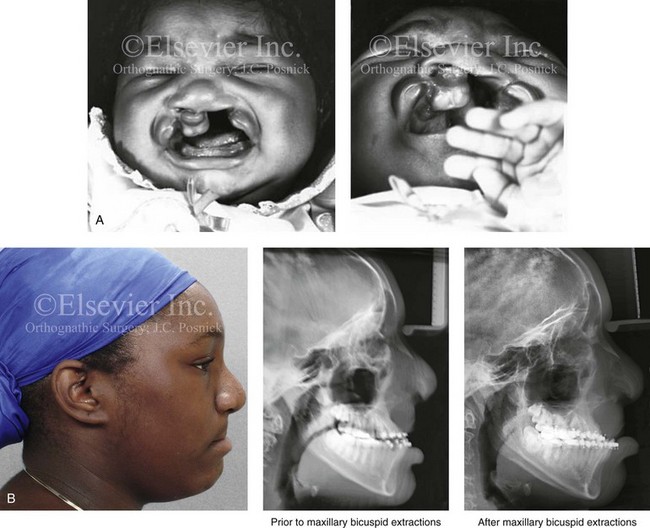

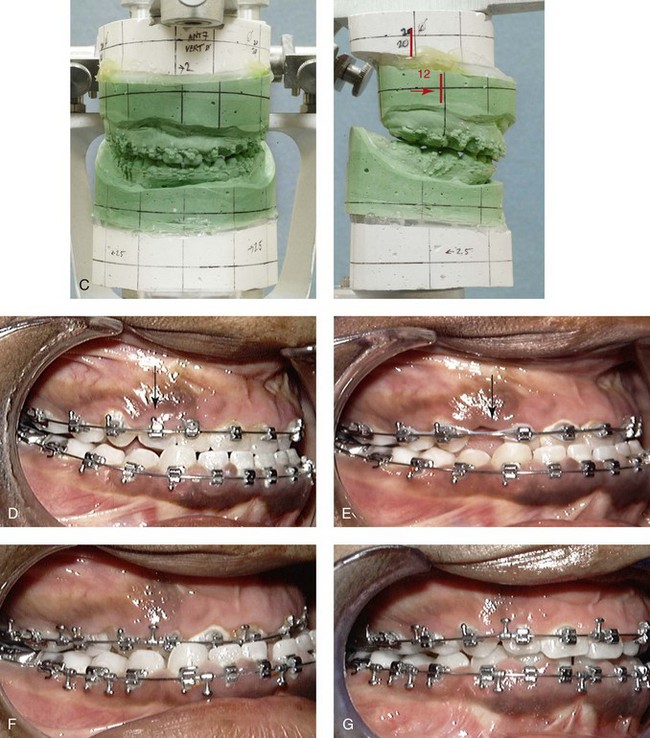

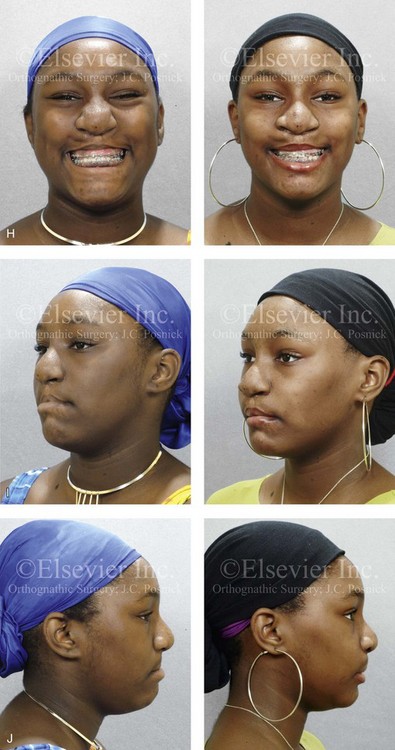

Figure 33-4 A child who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent lip and palate repair during infancy and early childhood by another surgeon. During the mixed dentition, she was referred to this surgeon with a mobile premaxilla, alveolar and palatal defects, and residual labial and palatal fistulas. She had the congenital absence of several permanent teeth. She underwent a short phase of orthodontic expansion and then successful iliac grafting and fistula closure during the mixed dentition. As a teenager, she underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic/intranasal surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included standard Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement and vertical shortening); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, The patient is shown at the time of birth. B, Facial and lateral cephalometric radiographic views during the adult dentition before and then after maxillary extractions with orthodontic retraction. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. D, Occlusal view during the adult dentition before extractions. E, Occlusal view after extractions and before orthodontic decompensation. F, Occlusal view after orthodontic retraction and before surgery. G, Occlusal view early after surgical correction. H, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. I, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. J, Profile views before and after reconstruction. K, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction.

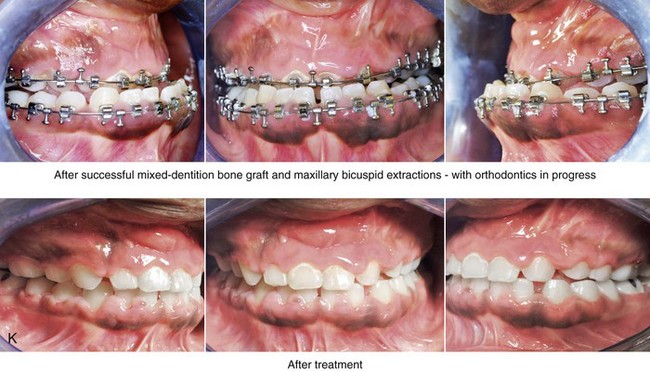

Figure 33-5 A 17-year-old girl who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. She underwent lip repair by this surgeon during childhood. This was followed at another institution by cleft palate repair; a columella lengthening of the nasal soft tissues when she was 5 years old; a pharyngeal flap for the management of velopharyngeal insufficiency when she was 7 years old; and then bone grafting to the alveolar clefts when she was 8 years old. She was referred back to this surgeon when she was 17 years old and found to have cleft nasal deformities, chronic obstructed nasal breathing, severe maxillary hypoplasia, secondary deformities of the mandible, and retained wisdom teeth. The maxilla had been successfully grafted with orthodontic closure of the cleft dental gaps. The patient then underwent reconstruction by this surgeon, including maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in two segments with differential repositioning (horizontal advancement +14 mm, vertical lengthening +5 mm, cant correction, and transverse narrowing) with interpositional grafting; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (asymmetry correction); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal base recontouring; and the removal of retained wisdom teeth. Before surgery, she underwent a nasoendoscopic speech assessment that demonstrated the satisfactory closure of the left lateral port with incomplete closure of the right lateral port (i.e., small air leakage). She maintained adequate velopharyngeal closure after surgery. Orthodontic maintenance and detailing continued and were followed by a removable maxillary retainer and a fixed lower anterior retaining wire. One year later, the patient underwent cleft rhinoplasty that included nasal osteotomies, the modification of the lower lateral cartilages, and a rib cartilage (caudal strut) graft. Note that ideal nasal aesthetics were compromised after a columella lengthening procedure that caused scarring of the soft tissues of the columella and distortions of the alar rims and tip. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views with orthodontic appliances in place and then after reconstruction. F and G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

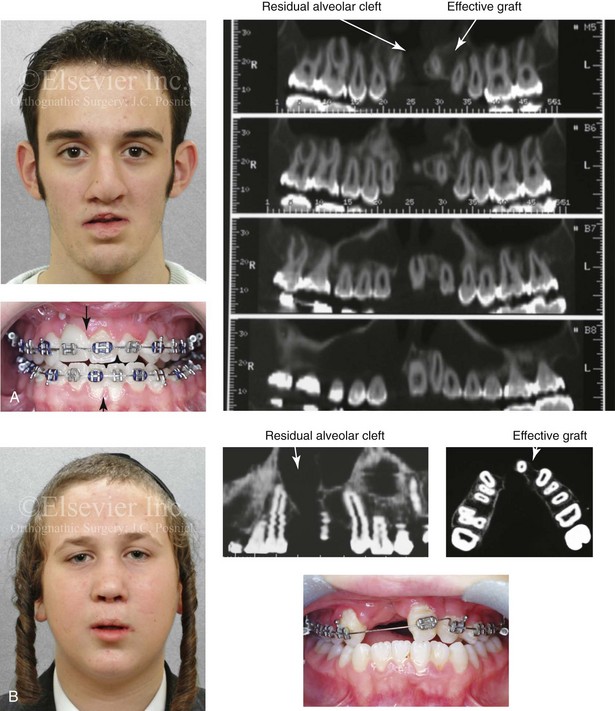

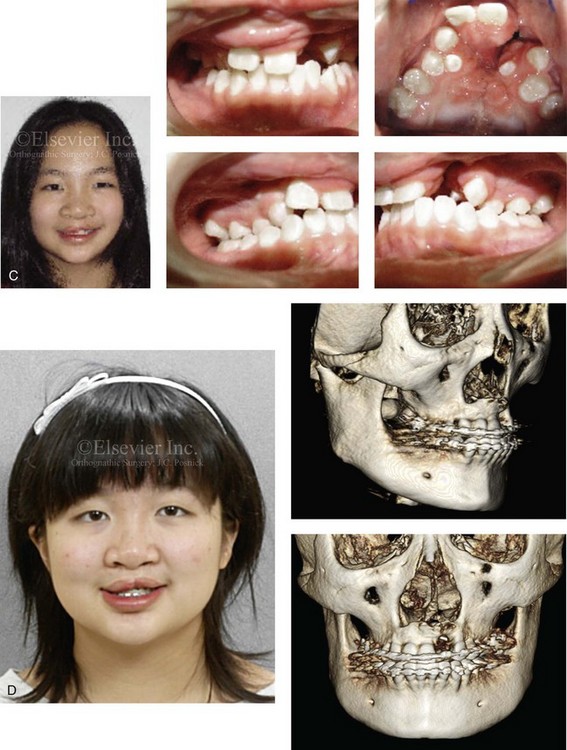

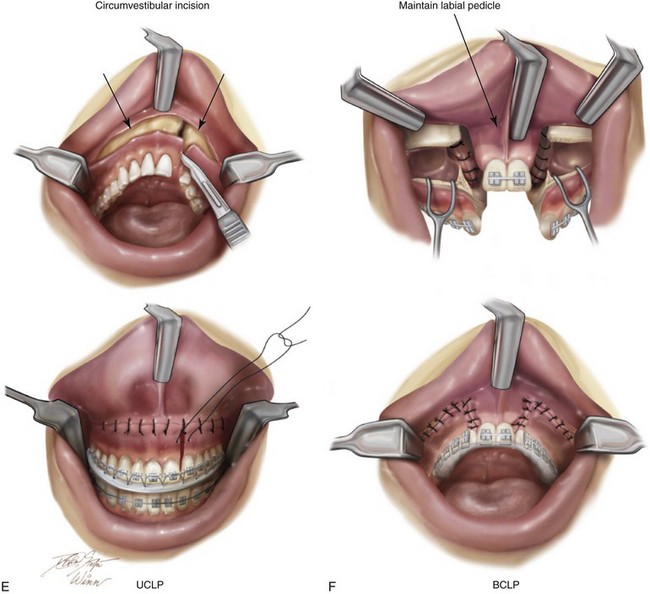

Figure 33-6 Three young adults who were born with bilateral cleft lip and palate are shown. Each had undergone bone grafting during the mixed dentition at another institution. Facial, occlusal, and computed tomography scan views indicate successful grafting at one cleft site but not at the other. It is important to make this determination when orthognathic surgery is required. If successful grafting was accomplished at one cleft site, then a circumvestibular incision can be made with full down-fracture, as one would for an ungrafted unilateral cleft alveolus. If successful grafting was not accomplished on either side, then a modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments would be required to maintain circulation to each of the three segments (i.e., the premaxilla, the left posterior segment, and the right posterior segment). This is done to avoid the complication of aseptic necrosis of the premaxilla (see Fig. 33-17). A, A teenager who was born with van der Woude syndrome and bilateral cleft lip and palate. He underwent successful grafting of one cleft site but not the other at another institution. He presented to this surgeon for orthognathic surgery. Facial, occlusal, and computed tomography scan views are shown. B, A teenager who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent successful alveolar grafting on the left side but not the right at another institution. He presented to this surgeon for orthognathic surgery. Facial, occlusal, and computed tomography scan views are shown and confirm these facts. C, A teenage girl who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent successful alveolar grafting on the right side but not the left. She then presented to this surgeon for orthognathic surgery. Facial and occlusal views when the previous patient was 7 years old, before grafting. D, Computed tomography scans of the same girl when she was 16 years old confirm successful grafting on right side but continued alveolar clefting on left side. E, Illustrations of incisions for a modified Le Fort I osteotomy in two segments either for a patient with unilateral cleft lip and palate and an open cleft or a patient born with BCLP and a successful graft on just one side. Part E modified from an original illustration by Bill Winn. F, Illustrations of the incisions required to maintain circulation to each of three segments in an unsuccessfully grafted case of bilateral cleft lip and palate.

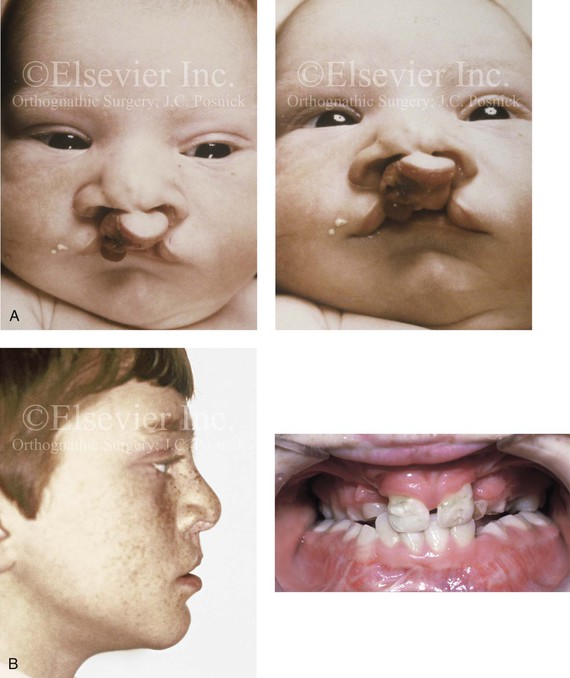

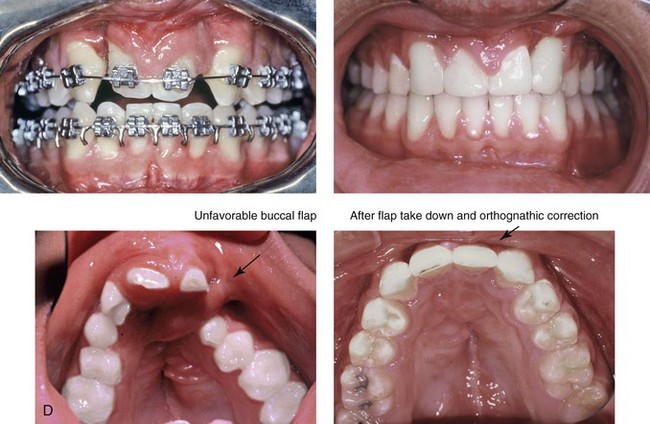

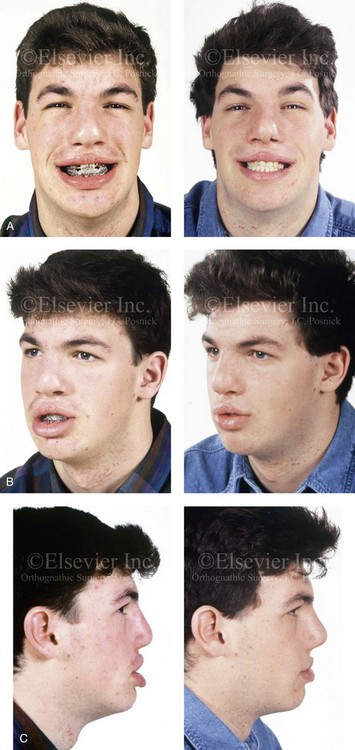

Figure 33-7 An 18-year-old boy was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate (![]() Video 14). He underwent lip and palate repair during childhood. Mixed-dentition grafting was not successful. He was then referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with closure of an oronasal fistula, alveolar defects, and cleft–dental gaps; and stabilization of the premaxilla with interpositional bone graft; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (correction of asymmetry); an osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement) and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views at before cleft lip and palate repair. B, Profile and occlusal views during the mixed dentition. Iliac grafting by another surgeon was not successful. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before and 2 years after reconstruction. A degree of relapse (skeletal versus dental) has occurred. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction (

Video 14). He underwent lip and palate repair during childhood. Mixed-dentition grafting was not successful. He was then referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with closure of an oronasal fistula, alveolar defects, and cleft–dental gaps; and stabilization of the premaxilla with interpositional bone graft; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (correction of asymmetry); an osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement) and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views at before cleft lip and palate repair. B, Profile and occlusal views during the mixed dentition. Iliac grafting by another surgeon was not successful. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before and 2 years after reconstruction. A degree of relapse (skeletal versus dental) has occurred. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction (![]() Video 14). C, D, E (top center, bottom center), from Posnick JC, Tompson B: Modification of the maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in cleft-orthognathic surgery: the bilateral cleft and palate deformity, J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51:2-11, 1993.

Video 14). C, D, E (top center, bottom center), from Posnick JC, Tompson B: Modification of the maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in cleft-orthognathic surgery: the bilateral cleft and palate deformity, J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51:2-11, 1993.

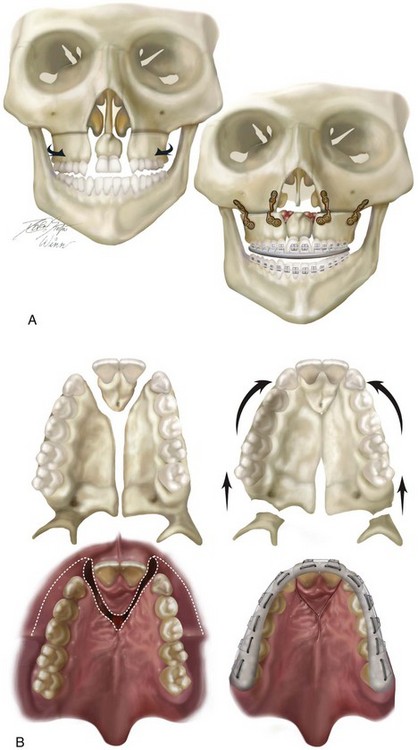

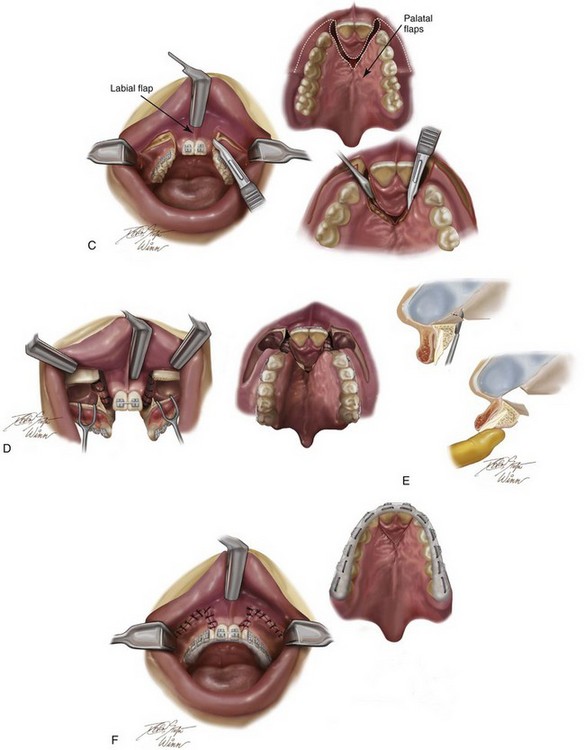

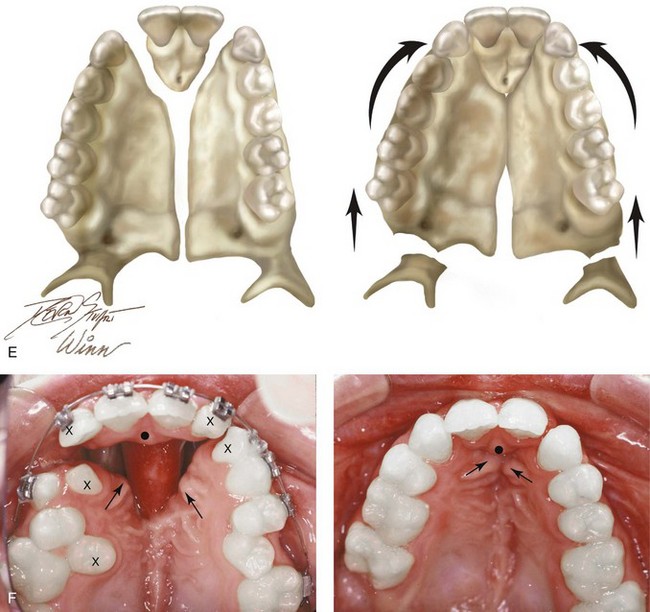

Figure 33-8 Illustrations of modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments used when mixed-dentition grafting has not been successfully accomplished (i.e., residual fistula, alveolar clefts with mobile premaxilla, and cleft dental gaps) and maxillary hypoplasia requires orthognathic surgery. A, Illustrations of a patient with bilateral cleft lip and palate before and after three-part maxillary osteotomies with repositioning of the segments. Septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction, are also shown. Skeletal views demonstrate anatomy before and after a modified Le Fort I osteotomy is three segments as described. B, Palatal views of bone segments before and after repositioning for the closure of cleft–dental gaps. Both skeletal and soft-tissue views are shown. Early after surgery, a prefabricated splint remains secured to the maxillary dentition. Parts A, C-F, modified from an original illustration by Bill Winn. C, Illustrations of incisions for modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments for the treatment of bilateral cleft lip and palate. D, Illustrations of down-fractured lateral segments demonstrating exposure for nasal-side closure of an oronasal fistula. E, Illustration of premaxillary osteotomy carried out on the palate side (vomer osteotomy) with the use of a reciprocating saw. F, Illustration demonstrating oral wounds sutured at the end of the procedure. Note that no sutures are required on the palate side. (From Posnick JC: Cleft orthognathic surgery. In Russell RC (ed): Instructional Courses. Plastic Surgery Education Foundation, vol. 4, St. Louis, Mosby-Year Book, 1991, pp 129-157.)

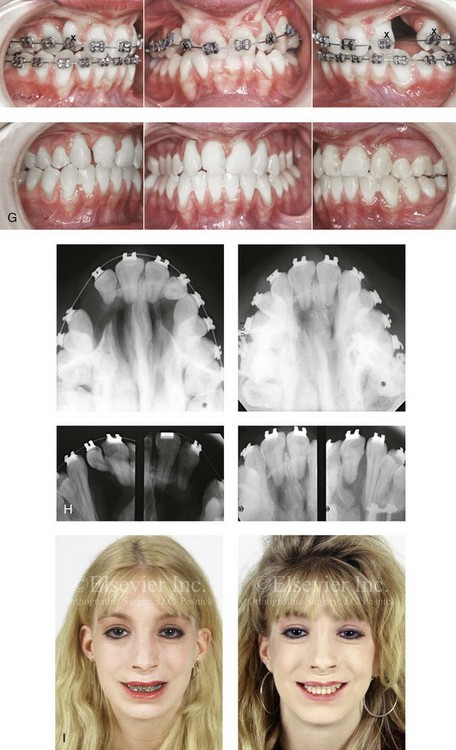

Figure 33-9 A 15-year-old girl was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. She underwent lip and palate repair during infancy and early childhood by another surgeon. She retained a large oronasal fistula in the incisal foramen region from the time of the initial palate repair. She had worn a palatal prosthesis to obliterate the opening, but this interfered with speech articulation and oral hygiene. She was referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic approach to close the large oronasal fistula, to stabilize the maxillary segments, and to restore her occlusion and periodontal health. As part of the preoperative orthodontic treatment, she underwent extraction of the five teeth for which there was inadequate alveolar bony support. During the operation, she underwent modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with differential repositioning and interpositional grafting for closure of the large oronasal fistula, the cleft–dental gaps, and the alveolar defects. She also underwent septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction to improve nasal airflow. Note that the maxilla was rehabilitated with the absence of the lateral incisors and a first bicuspid on the right side. A, Facial views before lip and palate repair. B, Palatal view during early childhood that indicates extensive oronasal fistula just after primary repair. C and D, Facial and palatal views at 15 years of age, when the patient was referred to this surgeon. E, Palatal view and illustrations demonstrating the patient’s skeletal anatomy before and after reconstruction. The “X”s mark the teeth that are planned for extraction. The black dot and the two arrows indicate the location where the palatal mucosa will come together. F, Palatal views before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation via the technique just described. G, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. H, Occlusal and periapical radiographs before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. I, Facial views before and after reconstruction.

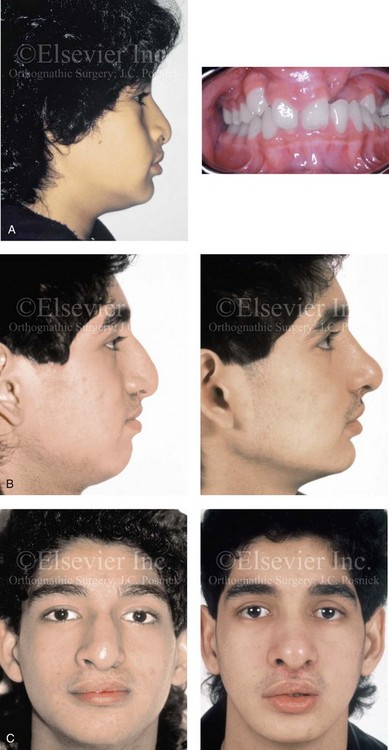

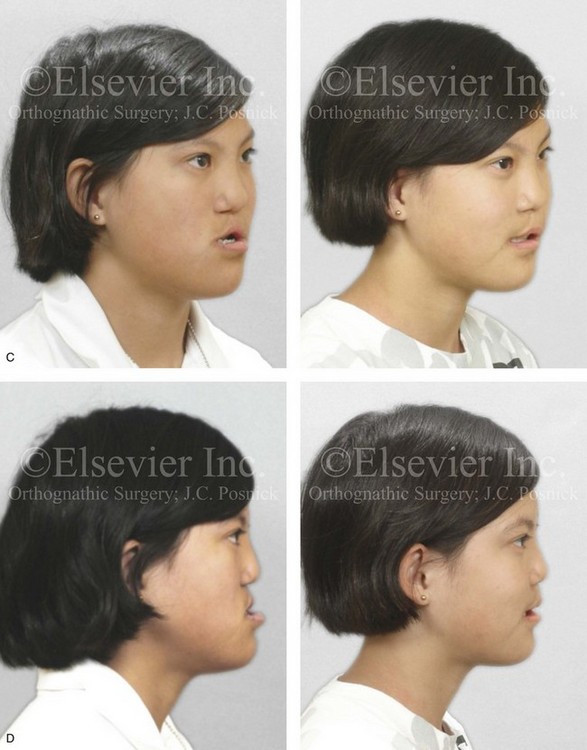

Figure 33-10 A 17-year-old boy of Hispanic descent was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. He underwent lip and palate repair during childhood and unsuccessful grafting during the mixed dentition. He was referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic approach. The patient’s procedures included a modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with differential repositioning and interpositional grafting (closure of the oronasal fistula, the alveolar defects, and the cleft–dental gaps; stabilization of the premaxilla); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. Six months later, he underwent an open rhinoplasty that included a rib cartilage (caudal strut) graft to improve nasal tip projection. A, Profile and occlusal views during the mixed dentition. B, Profile views during the teenage years before and after reconstruction. C, Frontal views during the teenage years before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. D, Occlusal and palatal views before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. B, C,D from Posnick JC, Witzel MA, Dagys AP: Management of jaw deformity in the cleft patient. In Bardach K, Morris HL, eds: Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate, Philadelphia, 1990, W.B. Saunders, p 538.

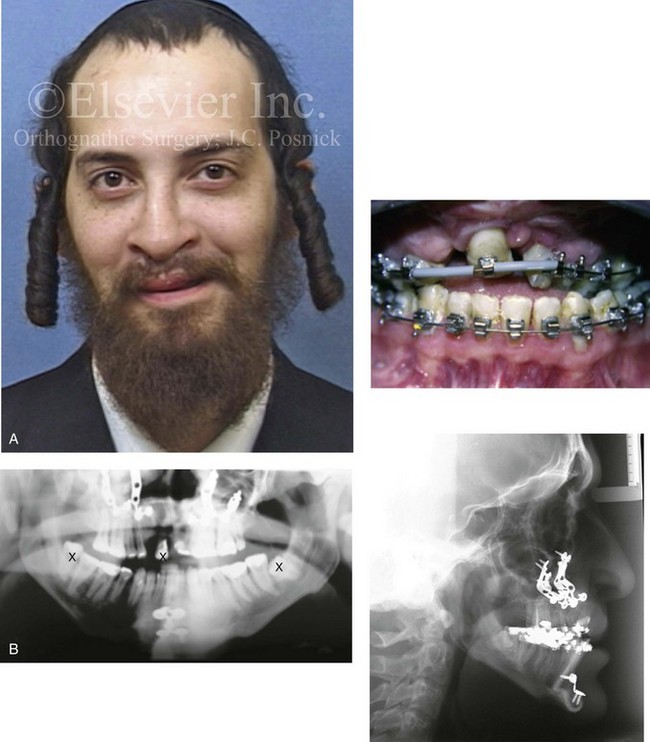

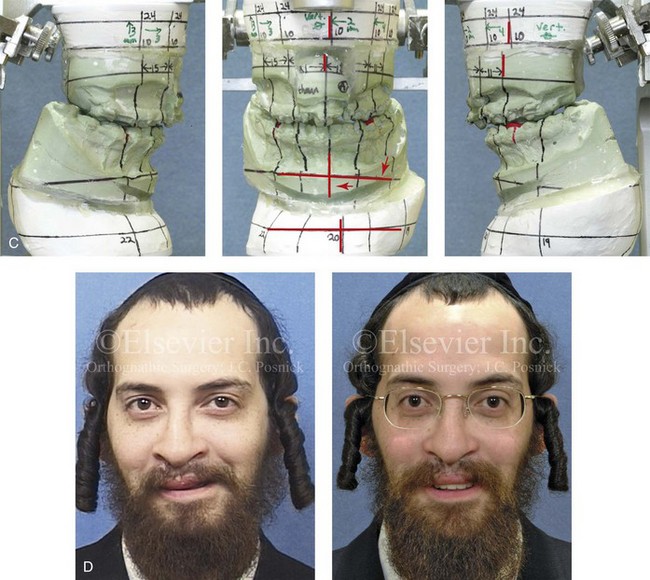

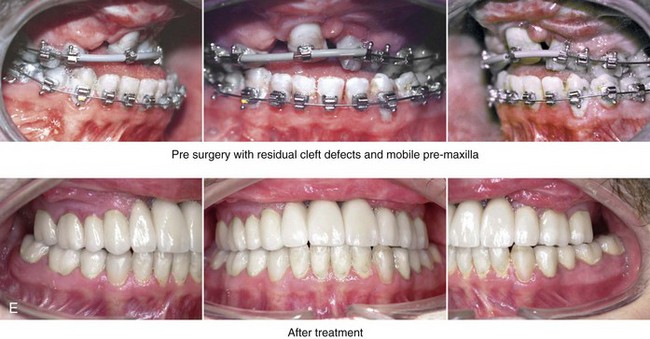

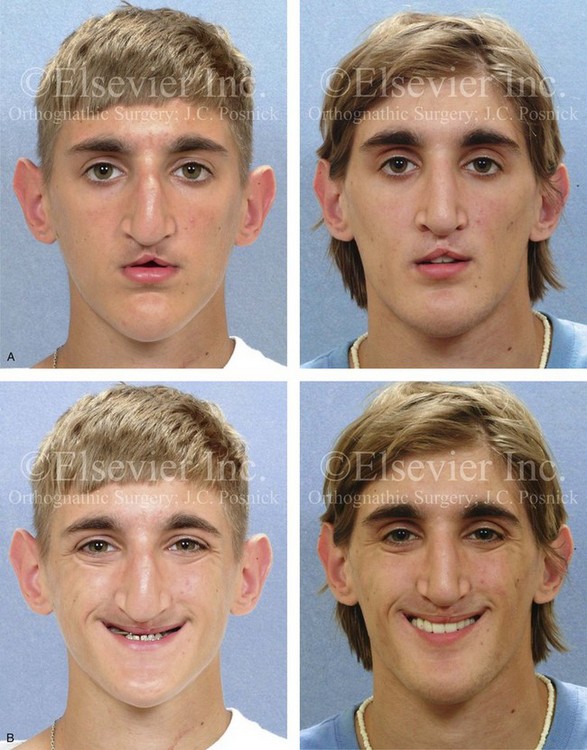

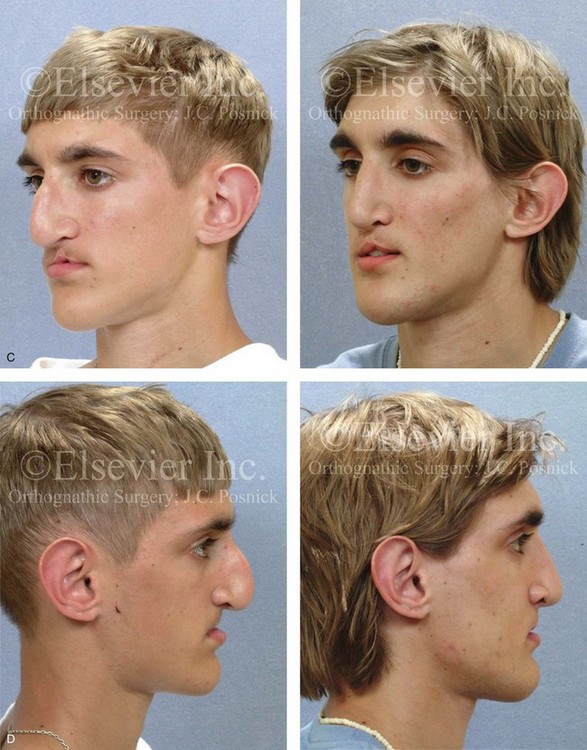

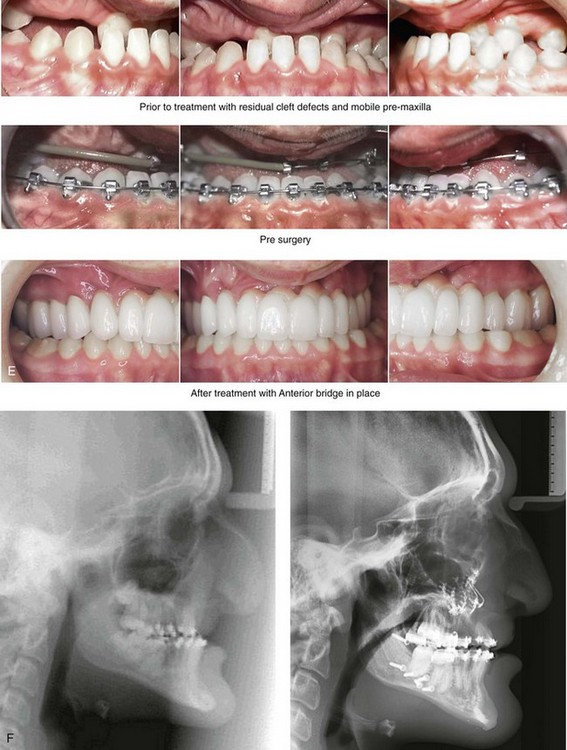

Figure 33-11 A 19-year-old man was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. He underwent lip and palate repair during childhood but did not undergo grafting during the mixed dentition. He was referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic approach. The procedures included a modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with differential repositioning and interpositional grafting (closure of the oronasal fistula, the alveolar defects, and the cleft–dental gaps; stabilization of the premaxilla) as well as septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Occlusal views with orthodontics in progress and after reconstruction. E, Palatal views before and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

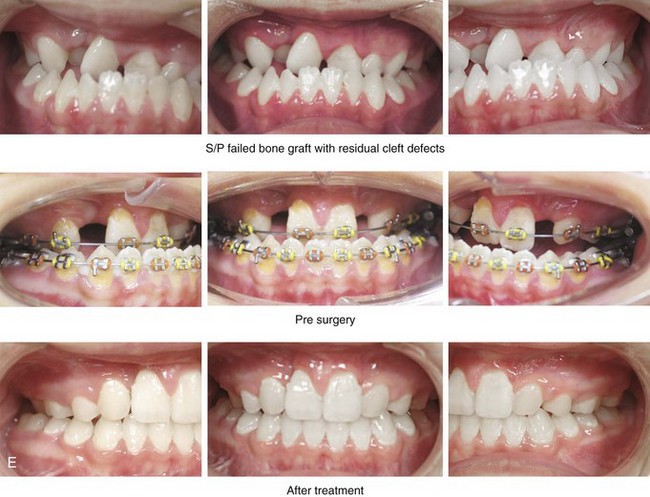

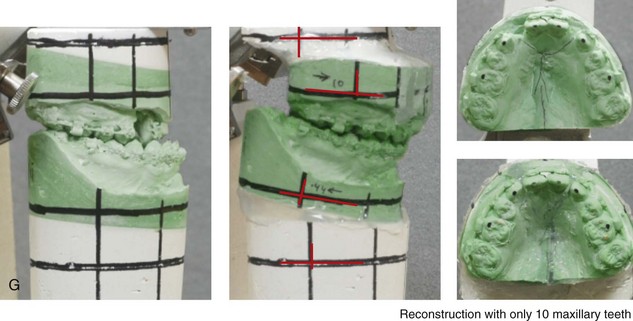

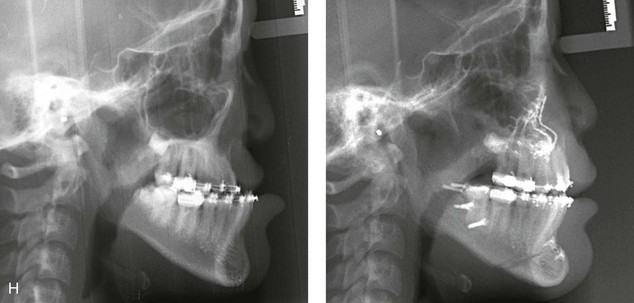

Figure 33-12 A 15-year-old girl was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. She underwent lip and palate repair during infancy. A superiorly based pharyngeal flap, lip scar revision, and tip rhinoplasty were carried out when she was 9 years old. She underwent iliac bone grafting to the alveolar clefts, without success. She was referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included modified Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with differential repositioning and interpositional grafting (closure of the oronasal fistula, the alveolar clefts, and the cleft–dental gaps, with stabilization of the premaxilla); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (clockwise rotation without set-back); oblique osteotomy of the chin (horizontal advancement); removal of retained wisdom teeth; and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and recontouring of the pyriform rims. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before the final phase of orthodontics, with orthodontics in preparation for surgery, and then after the completion of treatment. F, Palatal views before and after reconstruction. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric views before and after surgery. Note that the maxillary dentition is reconstructed with only 10 teeth; there was a congenital absence of the lateral incisors and the removal of the first bicuspids to relieve crowding. The maxillary wisdom teeth were impacted and not functional and therefore also removed.

Figure 33-13 An 18-year-old woman who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent lip and palate repair during childhood but did not undergo successful grafting during the mixed dentition. She was referred to this surgeon as a teenager and underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The procedures included lateral segmental osteotomies of the maxilla (anterior advancement of the segments with closure of oronasal fistulas, alveolar defects, and cleft–dental gaps and the stabilization of premaxilla with interpositional grafting) as well as septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. B, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. C, Palatal views before and after reconstruction. D, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. A, B, and C from Posnick JC: Discussion of: Orthognathic surgery in cleft patients treated by early bone grafting, Plast Reconstr Surg 87:840-842, 1991.

Figure 33-14 A boy with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent lip and palate repair during infancy. The premaxilla was distorted soon after birth, and it remained so into his teenage years. The patient presented to this surgeon when he was 16 years old for the management of residual dentoalveolar deformities. The maxillary (lateral) segments were well positioned, but the premaxilla was three-dimensionally distorted and mobile, bilateral labial and palatal fistulas were present, and the lateral incisors were congenitally absent. It was possible to surgically reposition (osteotomize) the premaxilla, to bone graft the defects of the palate and the floor of the nose, and to close the residual oronasal fistula during one procedure. A, Facial views in infancy after one side lip repair. B, Facial views during the mixed dentition after lip and palate repair. C, Frontal views with smile before and after premaxillary osteotomy and reconstruction. D, Occlusal views before and after premaxillary osteotomy for reconstruction. E, Palatal views before and after premaxillary osteotomy for reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

Figure 33-15 A 21-year-old man was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate. He underwent lip and palate repair, unsuccessful bone grafting, and unfavorable orthognathic surgery (Le Fort I and genioplasty) at another institution. He presented to this surgeon when he was 21 years old with a jaw deformity, malocclusion, and a limited dentition. He underwent evaluations by a periodontist, a prosthodontist, a surgeon, a speech pathologist, and an otolaryngologist. He then underwent a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. After periodontal treatment and further orthodontic (dental) decompensation, the patient’s reconstruction included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with differential repositioning and interpositional grafting (cant correction, closing down the cleft gap, closing of the fistula, horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and vertical adjustment); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (asymmetry correction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. This was followed by crown and bridge dental rehabilitation of the maxillary and mandibular dentition and ongoing periodontal surveillance. A, Frontal and occlusal views before redo orthodontics, surgery, and dental rehabilitation. B, Panorex and lateral cephalometric radiographs at time of presentation to this surgeon. C, Articulated dental models that indicate analytic model planning. D, Facial views with smile before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. E, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation.

Figure 33-16 A boy who was born with bilateral cleft lip and palate underwent lip and palatal repair and unsuccessful bone grafting at another institution. He presented to this surgeon when he was 17 years old with a severe jaw deformity and a limited dentition. He underwent evaluations by an orthodontist, a periodontist, a prosthodontist, a surgeon, an otolaryngologist, and a speech pathologist. He agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. After periodontal treatment, orthodontic (dental) decompensation was accomplished. The patient’s reconstructive surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses