Chapter 3

Treating the Periodontally Involved Furcation

Assuming that all other pocketing around a given molar may be eliminated and necessary crown length gained through appropriate periodontal osseous resective surgery, should buccal and/or lingual furcation involvements of the tooth be treated? Is it necessary to eliminate such furcation involvements? These questions must be answered before determining the fate of, or carrying out restorative therapy on, any periodontally involved bicuspid or molar.

Definitions of Furcation Involvements

When faced with a periodontally involved furcation, treatment decisions must be made in the context of an appropriate definition of therapeutic success. As already discussed, successful periodontal therapy is not characterized by short-term clinical health and immediate gratification. The net result of successful periodontal therapy should be an ease of patient maintenance, long-term predictability, and tooth retention in a healthy state for as long as possible. Predictability is defined as stable attachment levels and no continued loss of supporting bone or periodontal attachment.

Specific patient considerations may impact this definition of success. When considering a patient of advanced age, or one whose medical status is a contraindication to performing the desired therapy, compromises in the above definitions of success must be accepted. However, this discussion will assume no medical contraindications to therapy, and will ignore actuarial considerations.

The challenges confronting the concerned clinician when considering periodontal health, whether he or she is a periodontist or a restorative dentist, are well documented. Deeper pocket depths are less conducive to plaque control efforts and the maintenance of oral health than shallower pocket depths. The literature has reported that deeper pocket depths should be viewed as having greater potential for future periodontal breakdown than shallower pocket depths. Furcation involvements have been shown to represent a unique and challenging area of potential plaque accumulation and rapid periodontal breakdown. Numerous authors have demonstrated that the presence of furcation involvements may be utilized as a predictor for future attachment loss around the tooth in question.

The definitions of success following furcation therapy must be stringent and clinically relevant. Failure to wholly eliminate the horizontal and vertical components of a furcation involvement and thus the inability to provide the patient with a milieu that is conducive to maximum effectiveness of home-care efforts, must be deemed unsatisfactory. The appropriate definition of success following furcation therapy is elimination of all horizontal and vertical components of the furcation involvement, and no probing depths in excess of 3 mm on any aspects of the tooth in question.

The treatment approach chosen, whether it be resection, regeneration, a combination of resection and regeneration, or tooth removal and implant placement, is dependent upon the involved furcation morphology. It is therefore critical that easy-to-use, clinically applicable definitions of furcation involvements be employed to aid in the development of appropriate treatment algorithms.

Furcation defects are described as a function of the extent of periodontal destruction in both the horizontal and vertical dimensions. Horizontal furcation involvements are defined as follows:

A. Class I: Entrance into the furcation proceeds less than half of the horizontal dimension of the tooth (Fig. 3.1).

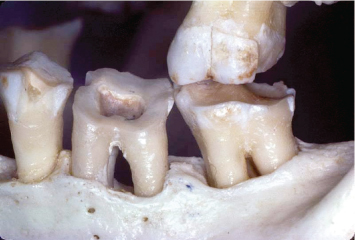

Fig. 3.1 Class I furcation involvements are noted on both molars.

B. Class II: Entrance into the furcation proceeds greater that half of the horizontal dimension of the tooth, but less than the full horizontal dimension of the tooth (Fig. 3.2).

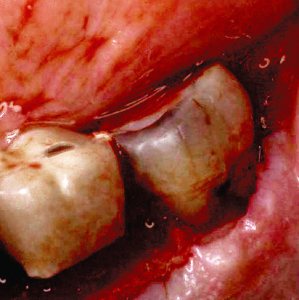

Fig. 3.2 Class II furcation involvements are present on both the first and second molars. The greater vertical component of the furcation involvement on the first molar renders treatment of this area more problematic than the Class II furcation on the second molar.

C. Class III: Entrance into the furcation proceeds along the complete horizontal dimension of the tooth, connecting both the buccal and lingual furcation entrances (Fig. 3.3).

Fig. 3.3 Class III furcation involvements are noted on both the first and second molars.

Vertical furcation involvements are defined as follows:

A. Subclass a: Loss of attachment apparatus along less than 25% of the vertical component of the furcation of the tooth.

B. Subclass b: Loss of attachment apparatus along more than 25% but less than 50% of the vertical component of the furcation of the tooth.

C. Subclass c: Loss of attachment apparatus along more than 50% of the vertical component of the furcation of the tooth.

Although the vertical component of a furcation involvement has significant ramifications in the treatment of Class II furcations, it plays a minimal role in the treatment of Class I furcations, unless the vertical involvement either extends to such a degree as to render attainment of appropriate osseous morphologies impossible, or reaches the apices of the tooth in question. In such situations, regenerative therapy or molar extraction and implant placement must be effected, depending upon the extent of the problem.

Examination of the root morphologies facing involved periodontal furcations demonstrates the difficulty, and often futility, of attempting to thoroughly debride these areas through the use of curettes and/or ultrasonic instrumentation, either through a closed or open-flap approach (Fig. 3.4). Molars presenting with additional roots, whether they be fully formed or vestigial in nature, pose an even greater challenge to the treating clinician (Fig. 3.5).

Fig. 3.4 The morphologies of the root surfaces facing a periodontally involved furcation on a mandibular molar render appropriate debridement difficult, if not impossible.

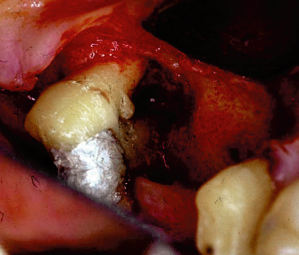

Fig. 3.5 The presence of an additional root complicates debridement of the periodontally involved furcation of the second molar.

A comprehensive review of the literature conclusively demonstrates that reduction of post-therapeutic pocket depths and the establishment of a stable, predictable attachment apparatus will result in a greater degree of long-term periodontal success with regard to the maintenance of oral health and the prevention of repocketing and reinitiation of periodontal disease processes.

An appropriate review of the literature also underscores the inadequacy of many therapies in the predictable treatment of the furcated tooth. “Maintenance” care, open-flap and closed-flap debridement of the furcation, chemical treatment of the root surfaces facing the involved furcation, and placement of various particulate materials without covering membranes or growth factors have failed to demonstrate predictable success in the treatment of the periodontally involved furcation.

Use of covering nonresorbable and resorbable membranes to treat involved furcations has traditionally met with a varying degree of success, although strict diagnostic criteria and a number of technical modifications to the conventional techniques will yield a high degree of success in the treatment of Class II buccal furcation involvements. The use of platelet derived growth factors and a number of other growth factors shows great promise in effecting regeneration of damaged bone and attachment apparatus in the periodontal involved furcation. However, this is not the forum in which to discuss such therapies.

It is critical to realize that certain therapeutic approaches are inadequate in the treatment of furcations of varying degrees of involvement, while other approaches are predictable and straightforward in resolving the problems associated with early furcation involvements.

There is no doubt that periodontally involved furcations may not be predictably maintained through root planing and curettage and repeated maintenance care sessions. In a longitudinal study of patients who refused active periodontal therapy and underwent only continuing maintenance care, Becker et al. (1) reported an overall rate of tooth loss of 9.8% in the mandible and 11.4% in the maxilla. Patients demonstrated a rate of tooth loss of 22.5% for mandibular furcated teeth and 17% for maxillary teeth with furcation involvements. These findings underscore the fact that teeth with furcation involvements are less amenable to maintenance care than their single-rooted counterparts.

The fact that teeth with furcation involvements are less amenable to maintenance care than their single-rooted counterparts is confirmed by Goldman et al. (2), who assessed tooth loss in 211 patients treated in a private periodontal practice through root planing, curettage, and open-flap debridement, and maintained for 15 to 30 years on a consistent recall schedule. Furcation involvements were not eliminated. The overall rate of tooth loss was 13.4%. Maxillary and mandibular teeth with furcation involvements were lost at a rate of 30.7% and 24.2%, respectively, a rate that was significantly higher than the incidence of nonfurcated tooth loss.

McFall (3) reported on tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease, who were maintained for 15 years or longer following active periodontal therapy. Once again, therapy did not eliminate the furcation involvements that were present. Of all teeth, 11.3% were lost over the course of observation. Maxillary teeth that demonstrated furcation involvements were lost at a rate of 22.3% over the course of this study. Mandibular furcated teeth were lost at a rate of 14.7%. Similar finding are reported throughout the literature (4–6).

As with other therapies, appropriate treatment of involved furcations depends upon many factors that are common to all aspects of dentistry. These include proper patient selection, establishment of adequate plaque control, formulation of a comprehensive overall treatment plan, and other factors previously discussed. However, a periodontally involved furcation also presents unique challenges that demand innovative treatment approaches and a realistic assessment of when to maintain a furcated tooth and when the tooth must be removed and replaced.

A study by Fleisher et al. (7) underscores the fallacy of believing that complete debridement of a periodontally involved furcation may be accomplished utilizing curettes and ultrasonic instrumentation. Fifty molars were treated through either closed curettage or open-flap debridement. All teeth were treated by experienced operators. The teeth were then extracted and stained for the presence of plaque and/or calculus. Assessment of the extracted and stained teeth demonstrated that only 68% of the tooth surfaces facing the involved furcation were calculus free.

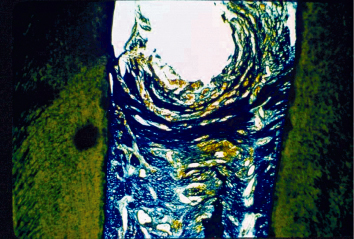

While there is no doubt that the utilization of microscopy and appropriate instrumentation will greatly improve upon this level of efficacy of furcation debridement, the three-dimensional structure of the involved furcation will remain (Fig. 3.6). The net result will be repopulation of this area by plaque, and reinitiation of a periodontal inflammatory lesion. Such an approach will “slow down” the progression of bone and attachment loss, and may prove valuable in an older patient or one who cannot or will not undergo more comprehensive therapy. However, such a treatment endpoint is not desirable in most other clinical scenarios. Therapy must be aimed at eliminating the periodontally involved furcation and providing the patient with a milieu that is amenable to appropriate plaque control efforts and reception of restorative therapy.

Fig. 3.6 Debridement of a furcation area, without elimination of the physical aspects of the furcation involvement bordered by the roots and the alveolar bone, does not halt the active disease process.

Cementoenamel projections represent another potential compromise in both periodontal health and periodontal treatment outcomes. Cementoenamel projections prevent the establishment of a connective-tissue attachment to the root surface, as connective-tissue attachment to enamel is not possible. As a result, these enamel projections are a potential funnel for bacteria into the entrance of the furcation, as the only barrier to such bacterial penetration is an overlying junctional epithelial adhesion.

As discussed in Chapter 1, epithelial adhesion has been shown to unzip in the face of a plaque front and the resultant inflammatory insult. A Class I cementoenamel projection, which extends less than 25% of the root trunk toward the furcation entrance, poses little concern with regard to periodontal health (Fig. 3.7). However, a Class II cementoenamel projection, which extends more than 50% of the dimension of the root trunk toward the furcation entrance but does not actually reach the furcation entrance, should be viewed as a weak link to the fiber-attachment periodontal defense system (Fig. 3.8). A Class III cementoenamel projection, which by definition extends to or into the entrance of the furcation, is an absolute compromise to periodontal health, as no connective-tissue attachment is present between the gingival sulcus and the entrance to the furcation (Fig. 3.9). Patients with such an abnormality are literally born with furcation involvements (Fig. 3.10). Failure to treat these areas in a timely and effective manner often leads to significant progression of periodontal disease problems in the furcation area and premature loss of the molar in question. Fig. 3.11 demonstrates a patient who presented with a Class III cementoenamel projection and was not treated through appropriate resective therapy. The result was continued periodontal breakdown. A Class III furcation involvement is now present on the tooth in question, which has a hopeless prognosis. Appropriate, timely intervention would have helped avoid such a development. The histologic specimen of the extracted tooth demonstrates attachment apparatus on the root surfaces, which were covered with cementum, and a lack of any attachment in the area of the cementoenamel projection (Fig. 3.12).

Fig. 3.7 A Class I cementoenamel projection is present on the first molar.

Fig. 3.8 A Class II cementoenamel projection is present on the first molar.

Fig. 3.9 A Class III cementoenamel projection is present on the first molar.

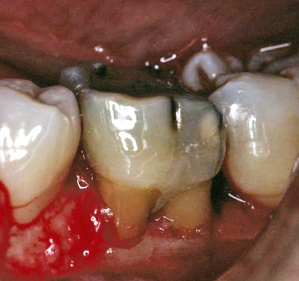

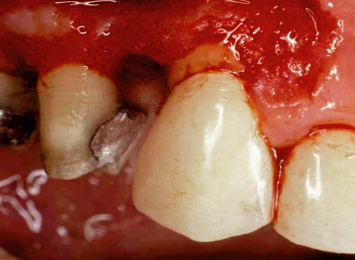

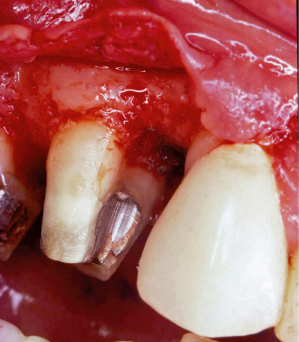

Fig. 3.10 Flap reflection reveals a Class III cementoenamel projection with the expected furcation involvement. The inability of the body to develop a connective tissue attachment to enamel renders this tooth highly susceptible to continued periodontal breakdown in the furcation area.

Fig. 3.11 Failure to treat a Class III cementoenamel projection in a timely and effective manner has resulted in the development of Class III furcation involvement and a hopeless prognosis for a mandibular first molar.

Fig. 3.12 A histologic section of the extracted tooth demonstrates both connective-tissue attachment to the cementum-covered root surfaces facing the furcation, and the lack of true attachment in the area of the cementoenamel projection.

Enamel pearls are also a significant concern (Figs. 3.13, 3.14). They represent both an area devoid of connective-tissue attachment to the root surface and a morphology that is conducive to plaque accumulation.

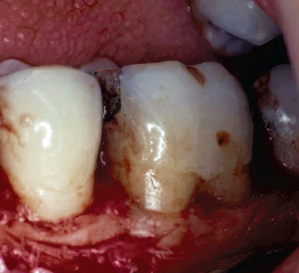

Fig. 3.13 The enamel pearl in the furcation area of the second molar both prohibits development of connective-tissue attachment in the region and serves as a nidus for plaque and calculus accumulation.

Fig. 3.14 Flap reflection reveals a large enamel pearl at the entrance of the mesial furcation of a maxillary molar. Note the periodontal destruction that has occurred in the area due to the inability to effect appropriate home-care measures.

Diagnosing Premolar Furcation Involvements

Mesial and distal furcation involvements on maxillary premolars are the most often ignored or misdiagnosed of all furcation entities. In addition, these furcation involvements pose unique dangers to overall periodontal health. An ignored mesial Class I furcation involvement on a maxillary first premolar, if allowed to progress, will result in significant loss of alveolar bone and attachment apparatus not only around the tooth in question, but also on the distal aspect of the adjacent cuspid (Figs. 3.15– 3.17). Such a development may compromise the integrity of the quadrant, or condemn a previously fabricated long-span fixed prosthesis. It is imperative that the furcation entrances of maxillary premolars be examined, diagnosed, and managed properly, to ensure long-term periodontal and restorative health.

Fig. 3.15 A patient presents with a 7-mm pocket on the mesial aspect of the maxillary first bicuspid. The patient has been under regular maintenance care at another office.

Fig. 3.16 A bitewing radiograph demonstrates the severe loss of bone and attachment apparatus which has taken place on the mesial aspect of the maxillary first bicuspid.

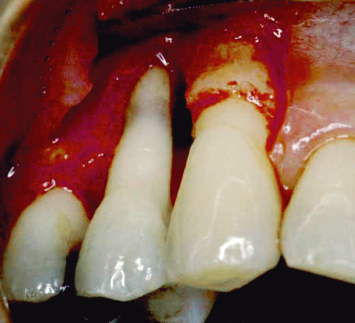

Fig. 3.17 Flap reflection reveals severe osseous loss around the maxillary first bicuspid. This tooth is now hopeless. Timely intervention when the furcation involvement first began to develop would have avoided this problem.

Treatment of Class I Furcations

The horizontal components of Class I furcation involvements may always be eliminated through ondontoplasty. If bone loss in the area of the Class I furcation involvement has a vertical component, which extends to such an extent that positive osseous architecture may not be developed, the problems in this region cannot be resolved through odontoplasty. Fortunately, such developments are rare with Class I furcation involvements. The roof of the furcation is recontoured to eliminate the cul de sac, which traps plaque, and the newly established tooth contours are carried onto the radicular surfaces of the tooth to create a continuous, smooth morphology conducive to patient plaque control efforts. Pocket-elimination surgery employing osseous resection with apically positioned flaps is performed at the same time. The net results of treatment are the elimination of deeper pocket depths and Class I furcation involvements. The post-therapeutic definition of success is no entrance of the probe into the furcation of the tooth and no probing depths in excess of 3 mm around the tooth. Coincident to the performed ondontoplasty is the elimination of all cementoenamel projections, thus enhancing the ability to form an appropriate attachment apparatus to protect the furcal entrance (Figs. 3.18, 3.19).

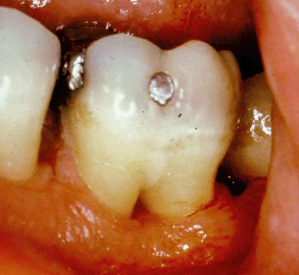

Fig. 3.18 The patient presents with a Class I buccal furcation involvement and a Class II cementoenamel projection.

Fig. 3.19 Following appropriate odontoplasty, the cementoenamel projection has been removed and the Class I furcation involvement has been eliminated. Mucoperiosteal flaps will now be sutured at osseous crest. The net result of treatment will be an area that is easily maintained by the patient.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE ONE

A patient presents having been temporized throughout the maxillary arch in anticipation of placing individual full-coverage restorations. Significant pocket depths had been noted on the mesial aspect of the maxillary first bicuspid. Flap reflection demonstrates a Class I furcation involvement (Fig. 3.20). The following treatment options must be considered by the clinician:

- “Maintenance” of the Class I furcation involvement through repeated scaling and root planing: As already discussed, this treatment approach will not halt the disease process. The net result will be continued bone and attachment loss in the area, jeopardizing both the first bicuspid and the cuspid.

- Extraction of the first bicuspid and placement of a three-unit fixed splint, extending from the second bicuspid to the cuspid: Such a treatment option poses two concerns. The first is that, if regenerative therapy is not performed at the time of tooth extraction, collapse of the socket and loss of some interproximal bone on the distal aspect of the cuspid and the mesial aspect of the second bicuspid are to be expected. The second concern is the greater difficulty in exhibiting appropriate home-care efforts around a three-unit fixed bridge than around individual crowns.

- Extraction of the first bicuspid with concomitant bone regeneration therapy and placement of a three-unit fixed splint, extending from the second bicuspid to the cuspid: Although this option addresses the concerns of bone loss subsequent to healing, assuming bone grafting is performed correctly, the concern with regard to increased difficulty of home-care efforts still remains.

- Extraction of the first premolar with immediate implant insertion and subsequent restoration: This option is highly predictable. However, there is an additional expense entailed in implant placement and restoration. The question becomes whether or not such therapy is required in this situation.

- Performance of odontoplasty to eliminate the roof of the involved furcation (Fig. 3.21) and render the area maintainable by the patient: This option presents with the advantage of eliminating the active periodontal problems, as well as the milieu which would help propagate further periodontal disease. In addition, the tooth is maintained, thus lessening the expense to the patient. It is important that the periodontist and restorative dentist communicate regarding the therapy that has been carried out, so that the restorative dentist does not attempt to cover all cut tooth structure, which would result in a restorative margin at the bone crest. In addition, care must be taken to properly contour the final restoration so as not to build in a prosthetic furcation involvement. An in-depth discussion of restorative contours following odontoplasty appears in Chapter 6.

Fig. 3.20 A patient presents with all maxillary teeth provisionalized for individual full-coverage restorations. Note the Class I furcation involvement on the mesial aspect of the maxillary first bicuspid. Failure to treat this area will severely compromise the long-term prognoses of the first bicuspid and cuspid.

Fig. 3.21 Following odontoplasty, the furcation involvement has been eliminated. Care must now be taken to finish tooth preparation at the gingival margin or slightly intrasulcularly, and to ensure that the contours of the restoration follow the newly created morphology of the tooth at the gingival area.

Ondontoplasty is highly predictable and may be carried out without a prosthetic commitment. If all therapy has been performed appropriately to manage osseous contours, including buccal and or palatal/lingual ledging, the attachment apparatus following healing of such therapy consists of approximately 1 mm of connective tissue attachment coronal to the alveolar crest, followed by approximately 1 mm of junctional epithelial adhesion. A 1–2-mm gingival sulcus will be present, against cut tooth structure. Such a minimal probing depth is easily maintainable by the patient, and does not pose a tooth sensitivity problem. After having performed ondontoplasty to eliminate Class I furcation involvements over 20,000 times in 29 years of private practice, only one instance has been encountered where tooth sensitivity persisted beyond 2 weeks post-therapy, unless caries or pulpal pathology had been present prior to treatment. Failure to eradicate early furcation involvements through odontoplasty will result in continued periodontal breakdown and attachment loss in the furcation area, and eventual tooth loss.

Elimination of Class I furcation involvements is conservative therapy. For example, if a 25-year-old patient presents with excellent home care, minimal probing depths, and a Class III cementoenamel projection in the buccal furcation area of a lower first molar, as evidenced by examination following retraction of unattached soft tissues in this area, two treatment approaches may theoretically be considered:

1. The patient could be placed on a strict maintenance schedule, and the clinician could attempt to maintain the furcation in question through repeated professional prophylaxis visits. The net results of such a treatment approach will be progression of periodontal di/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses