3

Surgical Exposure of Impacted Teeth

Aims of surgery for impacted teeth

Surgical intervention without orthodontic treatment

The surgical elimination of pathology

The principles of the surgical exposure of impacted teeth

Partial and full-flap closure on the palatal side

Buccally accessible impacted teeth

A conservative attitude to the dental follicle

Quality-of-life issues following surgical exposure

Cooperation between surgeon and orthodontist

The team approach to attachment bonding

Aims of Surgery for Impacted Teeth

In the past, the decision on how a particular impacted tooth should be treated was usually made by the oral surgeon and, by and large, the alternatives were decided and stage-managed by him. This situation has changed in recent years.

Prior to the 1950s, few orthodontists were prepared to adapt their skills and their ingenuity to the task of resolving the impaction of maxillary canines and incisors. Accordingly, the orthodontists themselves referred patients to the oral surgeon, who would decide if the impacted tooth could be brought into the dental arch. Where the circumstances were potentially favourable, the tooth would be surgically exposed and, when the surgical field was displayed fully, the surgeon would make his assessment of the prognosis of the case, and decide and act solely in accordance with his own judgement. In this way, many potentially retrievable impacted teeth were scheduled for extraction.

There are no surgical methods, other than transplantation, by which positive and active alignment of an impacted tooth may be carried out. The best a surgeon can do is to provide the optimal environment for normal and unhindered eruption and then hope that the tooth will oblige. In the past and with this in mind, therefore, those teeth that were considered worth trying to recover were widely exposed and packed with some form of surgical or periodontal pack to protect the wound during the healing phase and to prevent re-healing of the tissues over the tooth. For a variety of reasons, several other steps were taken, depending on the preferences and beliefs of the operator, with the aim of providing that ‘extra something’ that would improve the chances of spontaneous eruption still further. These measures were often very empirical in nature and included one or more of the following:

- clearing the follicular sac completely, down to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) area;

- clearing the bone around the tooth, down to the CEJ area, to dissect out and free the entire crown and the coronal portion of the root of the impacted tooth;

- ‘loosening’ the tooth by subluxating it with an elevator;

- bone channelling in the desired direction of movement of the tooth;

- packing gauze or hot gutta percha into the area of the CEJ, under pressure, in order to apply force to deflect the eruption path of the tooth in a particular direction.

In those years, few patients were referred to the orthodontist until full eruption had been achieved, and the tooth then needed only to be moved horizontally into line with its neighbours. Up to that point, the problem was considered to be within the realm of the oral surgeon. In many cases, ‘success’ in achieving the eruption of the tooth was pyrrhic and often subordinated to failure of a different kind, namely the periodontal condition of the newly erupted tooth and its survival potential – its prognosis. This was the inevitable result of the aggressive and overenthusiastic surgical techniques that had been used, specifically those listed above, which typically left the tooth with an elongated clinical crown, a lack of attached gingiva and a reduced alveolar crest height [1–6].

Surgical Intervention Without Orthodontic Treatment

We come across cases in which the only clinical problem relates to the impacted tooth, the occlusion and alignment being otherwise acceptable. For these patients, the following question needs to be addressed: what surgical methods are available that may be expected to provide a more or less complete solution without orthodontic assistance? To be in a position to answer this question, it is necessary to provide a description of the position of the teeth that will respond to this kind of treatment.

Exposure Only

A superficially placed tooth, palpable beneath the bulging gum, is an obvious candidate. This type of tooth may be seen in the maxillary canine area (Figure 3.1a), but also in the mandibular premolar area (see Figure 1.8) and the maxillary central incisor area, usually where very early extraction of the deciduous predecessor was performed while the immature permanent tooth bud was still deep in the bone and unready for eruption. Healing occurred, the gum closed over and the permanent teeth were unable to penetrate the thickened mucosa [7, 8]. Removing the fibrous mucosal covering or incising and resuturing it to leave the incisal edges exposed (Figure 3.2) will generally lead to a fairly rapid eruption of the soft tissue impacted tooth, particularly in the maxillary incisor area. The more the tooth bulges the soft tissue, the less likely is a reburial of the tooth in healing soft tissue and the faster is the eruption.

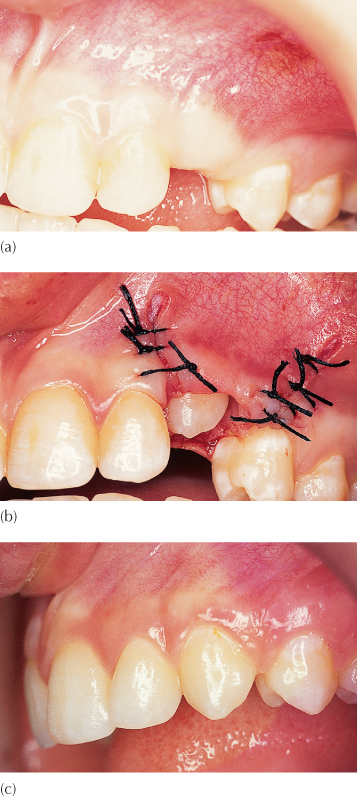

Fig. 3.1 (a) A 16-year-old female exhibits an unerupted maxillary left canine, which has been present in this position for two years and has not progressed. (b) The tooth was exposed and the flap, which consisted of attached gingiva, was apically repositioned. (c) At nine months post-surgery, the tooth has erupted normally.

(Courtesy of Professor L. Shapira.)

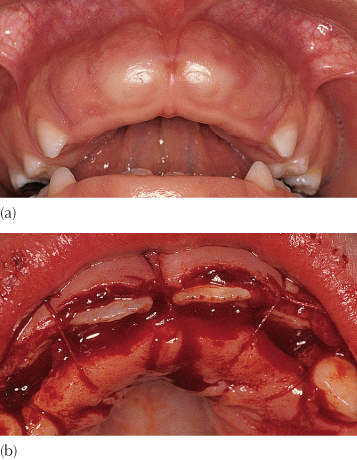

Fig. 3.2 (a) Soft tissue impaction of maxillary central incisors. (b) Apical repositioning of both labial and palatal flaps to leave the incisor edges exposed.

Exposure with Pack

Taking this one step further, we will understand that a less superficial tooth requires a more radical exposure procedure and may need a pack to prevent the tissues from re-healing over the tooth. While the surgeon may be rewarded with spontaneous eruption, this will take longer and a compromised periodontal result should be expected (Figure 3.3).

Fig. 3.3 Following exposure and packing the tooth has erupted spontaneously, but the bone level is compromised.

We have defined over-retained deciduous teeth as teeth still present in the mouth when their permanent successors have reached a stage of root development that is compatible with their full eruption. These deciduous teeth may then be considered as obstructing the normal development which would be expected to proceed in their absence. The deciduous teeth should be extracted, but provision should be made to encourage the permanent teeth to erupt quickly. Many of these permanent teeth with delayed eruption are abnormally low in the alveolus and are in danger of becoming reburied by the healing tissue of the evacuated socket of the deciduous tooth. Accordingly, the crowns of the teeth should be exposed to their widest diameter and a surgical or periodontal pack placed over them and sutured in place for 2–3 weeks. This will encourage epithelialization down the sides of the socket and, generally, prevent the re-formation of bone over the unerupted tooth.

Most surgeons and periodontists today will use a proprietary pack, such as CoePak™, to maintain the opening which, at the same time, acts as a dressing for the wound. A careful assessment of the space requirement should be made in these cases and consideration given to the need for space maintenance. It should be remembered that space loss in the mixed dentition may often be very rapid, and the erupting tooth may be arrested in its progress by its proximal contact with the adjacent teeth. Alternatively, particularly with regard to maxillary canines, placement of a removable acrylic plate, which is prepared before surgery, can be used to hold in a small pack over the exposed tooth [9].

Exposing and packing has recently been reintroduced and recommended for the treatment of severely palatally displaced maxillary canines [10]. When this is done, spontaneous resolution of even quite severe displacements has been claimed to occur in most cases, in the months that follow. This takes the form of at least partial eruption through the surgically created and pack-maintained opening and permits relatively easy access for attachment bonding and subsequent alignment of the tooth when appliance therapy is later initiated.

Exposure with Pressure Pack

Mesial impaction of a mandibular second permanent molar beneath the distal bulbosity of the first permanent molar is analogous to the more common mesial impaction of a third molar beneath the distal of the second. In either case, and in its mildest form, it is a condition that may sometimes respond to surgical intervention and packing only. This involves exposure of the occlusal surface of the tooth and the deliberate wedging of the pack in the area between the two teeth and leaving it there for 2–3 weeks. During this time, the pressure will often succeed in eliciting a distal movement of the impacted molar, which may then erupt more freely when the pack is removed. The degree of control available to the operator in judging the amount of pressure applied and the extent to which the pack interferes periodontally is minimal, although damage to the periodontium of the two adjacent teeth is possible. Success in bringing about an improved position of the tooth may thus not be matched by the health of its supporting structures. Others have used brass wire [11] or elastic separators to apply a similar disimpacting force.

The Surgical Elimination of Pathology

Soft Tissue Lesions

In Chapters 8 and 11 we shall refer more specifically to benign tumours and cysts. Surgery is the only treatment that is indicated for these conditions, in the first instance. This should be performed without delay, if only for reasons of obtaining biopsy material to confirm the innocence of a tentative diagnosis. Orthodontic treatment should be suggested then, but begun only after a filling-in of bone has occurred. At that point, there will be an improvement of the positions of the grossly displaced teeth, together with an improvement of the bony defect that will be evident in the anatomy of the alveolar bone in the area. However, this may take many months to occur. In the interim, the preparation of the patient for the proposed orthodontic treatment may be undertaken, which must begin with seeing positive results from a preventive dental health programme aimed at eliminating marginal gingival inflammation and reducing the caries incidence for that patient.

Hard Tissue Obstruction

Obstructive impaction invites the logical step of removing the offending body causing the non-eruption. This is performed by the surgeon and, on many occasions, it is without recourse to orthodontic assistance and enjoys varying degrees of success. In Chapter 5 we shall refer to the reliability of spontaneous eruption, following the various surgical procedures involved in the treatment of impacted incisors. For the present discussion, we must recognize that there is a significant number of cases in which eruption does not occur in a reasonable time-frame.

Following the removal of the obstruction, be it a supernumerary tooth, an odontome, residual deciduous roots or an infra-occluded primary tooth, the position of most unerupted teeth improves with time. However, many of these teeth do not erupt without assistance due to their severe displacement, which is a result of the existence of the erstwhile obstruction and the healing tissues.

A hard tissue body is generally made up of the dental tissues and, with its accompanying dental follicle, occupies much space. This causes a gross displacement of the developing tooth bud of the normal tooth, which is true in terms of both overall distance from its normal location and the usually marked deflection of the orientation of its long axis. Thus, the root or the crown of the tooth may be deflected mesially, distally, lingually or buccally, or displaced superiorly (in the upper jaw) or inferiorly (in the lower), compromising its chances for spontaneous eruption. Abnormally shaped roots may develop in the cramped circumstances in which they find themselves between the displacing influence of the pathological entity and the adjacent teeth, on the one hand, and the floor of the nose or lower border of the mandible [12], on the other. Teeth with abnormally shaped roots may have deviated eruption paths and do not always erupt spontaneously, although they may be successfully erupted with orthodontic appliances, provided their periodontal ligament (PDL) is normal.

Non-eruption of an impacted tooth disturbs the eruption pattern of the adjacent teeth, which then assume abnormal relationships to one another, usually characterized by space reduction and tipping. This then provides a secondary physical impediment to the eruption of the impacted tooth.

Infra-Occlusion

As we shall discuss in Chapter 8, infra-occluded permanent teeth are usually ankylosed to the surrounding bone and as such cannot respond to orthodontic traction. In many cases, the ankylosed area of root is minute and may be easily broken by a deliberate, but gentle luxation of the tooth. This is usually performed with an elevator or extraction forceps and is done in such a way as to loosen the rigid connection of the bony union, which is unbending. The tooth is not removed from its socket, nor is the principal aim even to tear the periodontal fibres. The purpose is to bring the tooth to a higher degree of mobility, beyond that characteristic of a normal tooth.

Unfortunately, the fate of the tooth that has undergone this procedure is usually a rehealing and reattachment of the ankylotic connection, leading to a return to the original situation. Accordingly, this approach can only be successful if a continuously active traction force is applied to the tooth from the time of its luxation. This force may then act to modify the rehealing of bone due to a localized microcosm of distraction osteogenesis [13, 14] that it causes. If the range of force is small and loses its potency between visits for adjustment, re-ankylosis will result and the tooth will not move. Thus, to be effective, it must be of sufficient magnitude to cause distraction and of sufficient range to remain active between one visit for adjustment and the next. The risk is that a poor biomechanical auxiliary, insufficient force levels or missed appointments may cause the exercise to founder, due to the re-establishment of the ankylosis bridge.

The Principles of the Surgical Exposure of Impacted Teeth

In general there are two basic approaches to surgically exposing impacted teeth, described below.

The Open Eruption Technique

Historically, the first method used to uncover impacted teeth left the tooth exposed to the oral environment, while surrounded by freshly trimmed soft tissue of the palate or labial oral mucosa, following the removal of the mucosa and bone actually covering the tooth. This is known as the open eruption technique and it may be performed in two ways.

The window technique involves the surgical removal of a circular section of the overlying mucosa and the thin bony covering. For most labially displaced teeth, due to their height, this entire surgical procedure would most likely only be possible above the level of attached gingiva (Figure 3.4), in the mobile area of the oral mucosa. Notwithstanding, it is clear that this is the simplest, most conservative and most direct manner to expose a tooth which is palpable immediately under the oral mucosa and it may often be accomplished with surface anaesthetic spray only. An attachment may then be bonded to the tooth and orthodontically encouraged eruption may proceed without delay, to complete its alignment within a very short time. While this obviously represents a significant advantage in the treatment of a young patient, the long-term outcome of the procedure will be characterized by a muco-gingival attachment on the labial side of the tooth which is not of attached gustatory epithelium, but rather a mobile, thin, oral mucosa that does not function well as a marginal tissue, as has been widely documented in the periodontal literature. The only situation in which this exposure procedure is clinically advantageous is when there is a very wide band of attached gingiva and where a labially impacted tooth is situated well down in this band, such that a simple removal of the tissue overlying the crown will still leave 1–2 mm of bound epithelial attachment inferior to the free, movable, oral mucosal lining of the sulcus.

Fig. 3.4 (a) A high buccal canine exposed by circular incision of the sulcus mucosa. (b) Following alignment, the oral mucosa is attached directly to the gingiva.

(Courtesy of Dr G. Engel.)

By contrast, the palatal mucosa is very thick and tightly bound down to the underlying bone. Thus, no parallel precautions need to be made to ensure a good attachment for the final periodontal status of a palatally impacted tooth, following its eruption into the palate. When the window technique is used on the palatal side, the cut edges of the wound need to be substantially trimmed back and the dental follicle removed to prevent re-closure of the very considerable width of palatal soft tissue over the exposed tooth (see Figure 6.29). For a deeply buried palatal canine, the exposure will additionally need to be maintained using a surgical pack.

The apically repositioned flap is an alternative way of performing an open exposure technique on the buccal side. It is aimed at improving the periodontal outcome by ensuring that attached gingiva covers the labial aspect of the erupted tooth in the final instance. This is done by raising a labial flap, taken from the crest of the ridge, and relocating it higher up on the crown of the newly exposed tooth. This method, a recognized and accepted procedure in periodontics, was first described in the context of surgical and orthodontic treatment of unerupted labially displaced teeth by Vanarsdall and Corn [15]. In their method, and in the absence of the deciduous canine, a muco-gingival flap, which incorporates attached gingiva, is raised from the crest of the ridge (Figure 3.1). If a deciduous canine is present, the flap is designed to include the entire area of buccal gingiva that invests it, and the deciduous tooth itself is extracted. In either case, the flap is detached from the underlying hard tissue some way up into the sulcus, to expose the canine. The flap is then sutured to the labial side of the exposed crown of the permanent canine, to cover the denuded periosteum and overlie its cervical area, while the remainder of the crown remains exposed. Subsequent eruption of the tooth is accompanied by the healing gingival tissue and, when the tooth takes up its final position in the arch, it will be found to be invested with a good width of attached gingiva.

This particular method of exposure is best suited to buccally/labially impacted teeth which are situated above the band of attached gingiva, but which are not displaced mesially or distally from their place in the dental arch. If the case presents with more than a minor degree of horizontal displacement in the sagittal plane, a raised and full thickness soft tissue flap will denude the alveolar bone covering the adjacent tooth to an unacceptable degree, contraindicating the use of this surgical modality. In order to overcome this, a partial thickness surgical flap may be raised, which leaves the donor area invested with a connective tissue cover [16], which will heal over by epithelial proliferation.

With any form of open exposure surgery, the tooth acquires a new gingival margin which comprises the cut edge of gingival tissue, which will heal in this position and will move with the tooth as it is drawn down into its place in the arch. While the periodontal parameters may be very satisfactory, the appearance of the tissues surrounding the aligned tooth at the end of treatment by this method lacks a completely natural look and it is usually possible to distinguish the previously affected tooth with ease, even several years later (Figure 3.8).

The Closed Eruption Technique

The alternative approach to surgical exposure, the closed eruption technique, has an attachment placed at the time of the exposure and the tissues fully replaced and sutured to their former place, to re-cover the impacted tooth. This was described by Hunt [17] and McBride [18], although it seems to have been in use earlier [19, 20], and it is a procedure that may be used regardless of the height or mesio-distal displacement of the tooth. For a buccally impacted tooth, a surgical flap is raised from the attached gingiva at the crest of the ridge, with suitable vertical releasing cuts, and elevated as high as is necessary to expose the unerupted tooth. An attachment is then bonded and the flap fully sutured back to its former place. The twisted stainless steel ligature wire or gold chain, which is preferred by some clinicians, which has been tied or linked to the attachment, is then drawn inferiorly and through the sutured edges of the fully replaced flap. The surgical wound is, therefore, completely closed and the exposed tooth and its new attachment are sealed off from the oral environment. Spontaneous eruption is less likely to occur than when the tooth remains exposed following apical repositioning, and active orthodontic force will probably need to be applied to the tooth to bring about its eruption. Traction is then applied to the twisted stainless steel ligature or gold chain to bring about the full eruption of the tooth [18, 21, 22]. In this method, the tooth progresses towards and through the area of the attached gingiva several weeks or months after complete healing of the repositioned surgical flap has occurred and it creates its own portal through which it exits the tissues and erupts into the mouth. As such, it very closely simulates normal eruption and the clinical outcome will usually be difficult to distinguish from any normally and spontaneously erupting tooth, in terms of its clinical appearance and objective periodontal parameters.

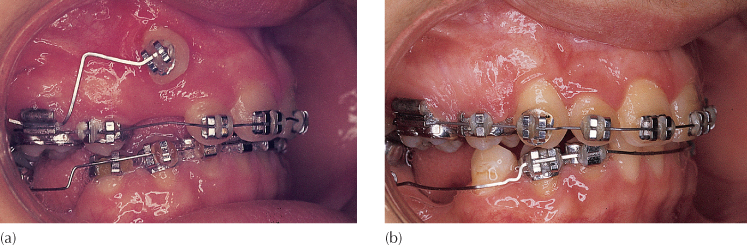

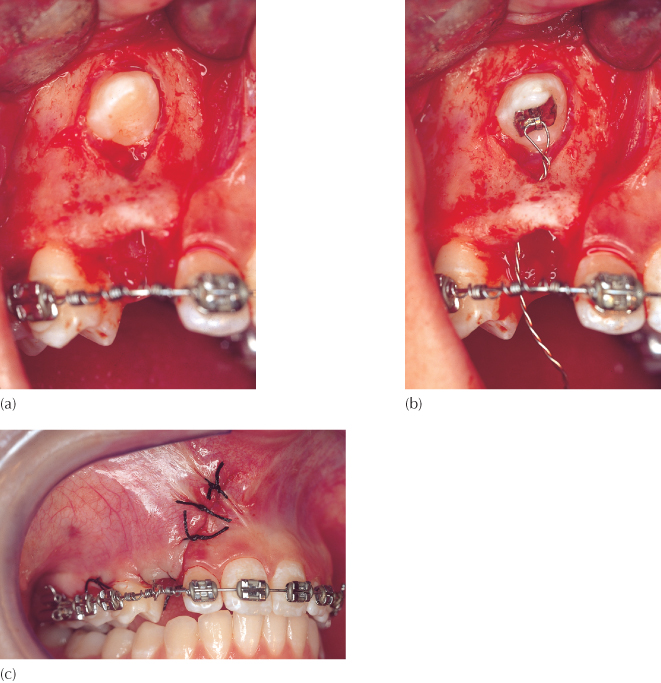

A modification of the closed eruption technique has been described by Crescini et al. specifically in respect of maxillary permanent canines [23]. In this procedure, a full buccal flap is raised from the attached gingival at the neck of the deciduous canine and adjacent teeth, to expose the surface of alveolar bone up to and including that covering the labially impacted buccal canine. The buccal crown surface of the canine is exposed and the deciduous canine extracted. The twisted steel ligature or gold chain linked to the eyelet, which is now bonded to the tooth, is threaded into the apical area of the recently vacated socket of the deciduous canine and drawn downwards to exit through its coronal end. No buccal bone is removed beyond that immediately overlying the crown of the exposed canine. The flap is now sutured back to its former position, leaving only the end of the ligature/gold chain visible through the socket of the deciduous canine. The aim of this aptly named ‘tunnel’ technique is to mimic even further the natural eruption process by applying extrusive force to move the impacted canine directly through the socket of the recently extracted deciduous canine (Figure 3.5). Furthermore, by retaining the buccal bridge of bone during surgery, the final outcome will show the aligned tooth to have an excellent bony support, in terms of both its width and level.

Fig. 3.5 Crescini’s tunnel variation of the closed eruption technique.

(Courtesy of Dr E Ketzhandler.)

(a) A very high labial canine has been exposed with a full flap exposure, which included the gingival margin of the extracted deciduous canine. The bridge of buccal bone is left intact. (b) An attachment is bonded to the palatal aspect of the permanent canine and its pigtail ligature is directed through the socket vacated by the extracted deciduous tooth. (c) The flap is sutured to its former place and vertical traction will draw the tooth down, maintaining alveolar bone on its labial side.

Each method has its advantages and its drawbacks from the points of view of efficacy of treatment, postsurgical recover and the overall treatment outcome in relation to aesthetics, periodontal prognosis and stability of the final result.

Efficacy of Treatment

Should the Orthodontist Be Present at the Time of Surgery?

The greatest inconvenience of the closed eruption technique is that it is preferable that the orthodontist be present in the operating room for bonding of the attachment before the flap is sutured back to its former place. It is true that many oral surgeons bond the attachments themselves. However, since the surgeon bonds orthodontic attachments far less frequently than does the orthodontist, the chances of bond failure are relatively increased – the more so since the surgeon, when working with only chair-side nursing assistance, will need to undertake both the task of maintaining a dry and uncontaminated tooth surface in a very haemorrhagic field and, at the same time, that of performing the bonding procedure. It should be emphasized that in the case of the closed eruption technique, bond failure will dictate the need for a second surgical intervention. If the attachment is to be bonded at a later visit, the orthodontist does not need to be present at the surgeon’s side for an open exposure case. However, this means that the surgeon must expose the tooth much more widely, place surgical packs and aim for healing by ‘secondary intention’ only, with attendant negative periodontal implications.

Of far greater importance and directly related to ensuring successful resolution of the impaction, the orthodontist is able to see the exact position of the crown, the direction of the long axis and the deduced location of the root apex, by being present. The height of the tooth and its relation to adjacent roots may all be noted, and the orthodontist may confirm or change the original plan for the strategy of its resolution, by direct vision, in the light of what he/she now sees ‘in the flesh’. The orthodontist will be in a position to decide exactly where the attachment should be placed from a mechano-therapeutic point of view and will bond it there. The orthodontist is also the best person to fabricate and place a suitable and efficient auxiliary to apply a directional force of optimal magnitude and a wide range of movement, and to do so at the time of or, preferably, immediately prior to surgery. It is not fair to expect the oral surgeon to be aware of how different attachment positions may affect the orthodontic or periodontic prognosis; nor should it be expected that he/she will be sufficiently experienced with the bonding technique to do this. Indeed, without the presence of the orthodontist, the surgeon may carry out the exposure of the tooth and place a bracket in the most convenient location that may seem to him/her to be entirely appropriate. At a subsequent visit, the application of traction by the orthodontist may need to be made in a particular direction which, because of an incorrectly placed attachment, is impossible to attain, and the tooth may cause damage to adjacent structures by being drawn in an unfavourable direction.

It becomes evident that the inconvenience caused to the orthodontist by his/her being present at the exposure is handsomely rewarded in the long run by far greater control of the destiny of the impacted tooth, including efficacy and predictability of treatment and the quality of outcome.

The Reliability of Bonding

For the patient who has had an open exposure procedure, the reliability of bonding at a subsequent visit is, paradoxically, much poorer than when the attachment bonding is performed at the time of surgery [24] for the following reasons.

During a closed surgery procedure, a wide tissue flap is usually raised, which provides good visibility and access, especially to a deeply buried tooth (Figure 3.6). The margins of the wide flap are distant from the tooth, enabling better control of moisture and bleeding in the immediate area. The orthodontist can bond the attachment efficiently, while the surgeon and the nurse maintain haemostasis and the necessary dry field. In contrast, an open exposure involves raising a small flap in the area immediately surrounding the tooth and maintaining the patency of the opening (usually with the help of a periodontal pack) until an attachment is bonded at a later date. At that visit, secondary healing will have occurred, and the newly epithelialized cut surface will be very sensitive to any form of manipulation. Accordingly, the patient will have avoided brushing the area and a degree of inflammation will be present, due to the accumulation of plaque and the freshness of the healing wound. Prophying the tooth under these conditions of restricted access and fragile haemorrhagic tissue is not conducive to successful bonding. In addition, the presence of eugenol from the periodontal pack may inhibit composite polymerization and thereby weaken the bond strength.

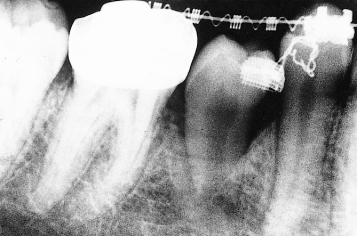

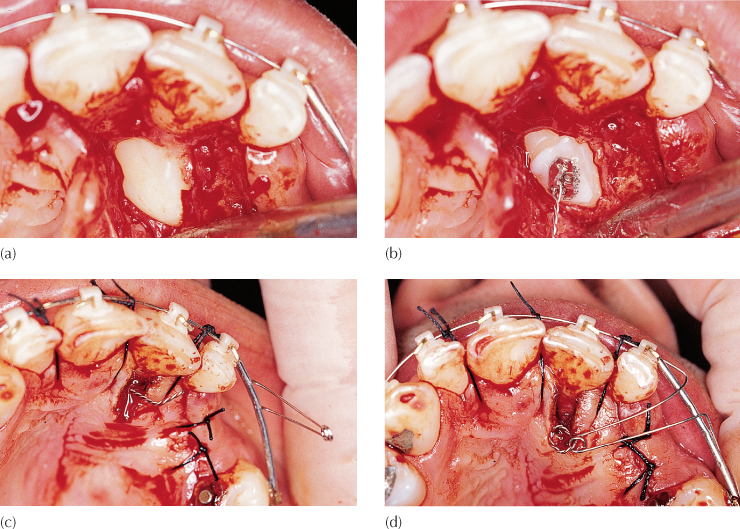

Fig. 3.6 (a) The crown of an impacted canine is exposed using a wide flap, but with removal of minimal bone. The unexposed crown lies between the roots of the central incisors, having traversed the midline suture. (b) An attachment is bonded, while haemostasis is maintained by the surgeon. (c) The flap has been divided to accommodate the ligature pigtail in its desired position, before being fully replaced and sutured. (d) The labial spring auxiliary loop, seen in its passive position in (c), has been turned inwards towards the palate and secured to the stainless steel ligature pigtail.

When orthodontic brackets are bonded in day-to-day practice, the teeth are first cleaned, using a rubber cup and pumice. The aim of this procedure is to remove extraneous materials, which include soft plaque, dried saliva, organic and chemical staining, and deposits which adhere or adsorb to the enamel prisms and which may prevent penetration of the etchant. Once these are removed, the enamel surface becomes vulnerable to the orthophosphoric acid liquid or gel, which is the key to a successful adhesion of the attachment. In contrast, newly exposed impacted teeth are completely free of these extraneous materials. Their only covering is Nasmyth’s membrane, which is made up of the enamel cuticle and the reduced enamel epithelium and is about 1 micron thick. This appears to present no barrier whatsoever to the etching effect that is achieved by the application of orthophosphoric acid [24]. Accordingly, there is no advantage to be gained by pumicing these teeth as part of the bonding procedure. Rather, the reverse is the case. To permit the introduction of a hand piece and rubber cup or a small electric toothbrush or hand brush, exposure has to be considerably broader for prophylaxis to be effective. It is difficult to control these implements during the brushing exercise and, as a direct consequence, the brush or cup traumatizes the exposed bone and soft tissues. This generates renewed bleeding, while giving rise to a dispersal of the pumice over the immediate surgical field. Prophylaxis is therefore completely superfluous.

A significant problem with the closed eruption technique is sometimes caused by a poor choice of orthodontic attachment. Since the mid-buccal position of this tooth is easy to expose and to bond to, the orthodontist may be tempted to use a conventional orthodontic bracket in this instance [25] and there is no contradiction in doing this with an open eruption technique.

However, due to the buccal prominence of the tooth, the lack of buccal bone, and the relative tightness of the replaced flap, damage may be caused to this muco-gingival tissue by the bulk of wide and high profile conventional brackets (see Figure 4.3), with the closed eruption technique. This may lead to a breakdown of the overlying tissue, to cause a dehiscence or even ‘buttonholing’ (Figure 3.7) of the mucosa. In such circumstances, any attachment placed on the tooth should be as small as is practical and with a minimum height profile, in order that it will cause as little adverse effect on the gingival tissues as possible, on its way through. This will be dealt with more fully in the next chapter.

Fig. 3.7 Buttonholing.

Duration of the Surgical Procedure

When the surgical field is opened, there is considerable bleeding at the cut edges of the surgical flap and of the whole area that has been exposed by its reflection. The exposed area needs to be wide enough to afford the surgeon good visibility to perform the needed episode accurately and efficiently and, in order to fulfil any task, whether this be to remove a supernumerary tooth, dissect away bone, free an impacted tooth from its surrounding tissues or bond an attachment, good haemostasis must be achieved. This is usually done using high-power suction, packs of various sorts and the application of pressure. If the duration of the surgically inflicted wound is excessive, the surface of exposed bone will become desiccated, leading to cell death and it may take several weeks or months of healing before the necrotic section of bone is resorbed and replaced with healthy new bone. More importantly, desiccation of exposed roots of teeth, periodontal ligament and cementum may occur, which will damage these tissues – a factor that may sometimes be compounded by the over-generous use of acid etchant. Adverse changes may then occur in these tissues which could result in impairment of the eruption mechanism of the tooth. This may be irreversible and result in failure to elicit eruption of the impacted tooth, even when traction is applied. The reader is referred to the sections on ankylosis and invasive cervical root resorption in Chapter 7 for a description of these phenomena. It is therefore important to select a surgical procedure or technique that may be completed in as short a time as possible.

On the face of it, it would seem that an open exposure should take less time than a closed procedure. However, the results of a study performed by our group have indicated quite the opposite [26, 27]. It seems that the wide tissue flap raised in the closed procedure improves visibility, permitting easier and quicker exposure of the impacted tooth, thus shortening its overall duration. Suturing the full flap back to its former place is also considerably quicker and neater than suturing an apically repositioned flap into its new position with accompanying pack placement.

Initiation of Traction

During a closed surgical technique procedure, the orthodontist may or may not be present but it is imperative that an attachment be bonded at the time. Absence places the onus on the surgeon to do this. It is obviously propitious to apply the eruptive force to the impacted tooth immediately, taking full advantage of the prevailing anaesthesia.

In contrast, when open surgery is performed, the presence of the orthodontist is unnecessary, the intention being to prepare the stage for the placement of an attachment at a future date by the orthodontist in his/her office. This means that the surgeon must complete the exposure in such a manner as to be sure that the tissues will not heal over and make the tooth inaccessible in the few post-surgical weeks until an attachment is bonded in the orthodontist’s office and traction may begin. Since orthodontic procedures in general do not require local anaesthesia, the orthodontist is unlikely to offer this to the patient at this orthodontic appointment, and additional delay in the application of force is inevitable due to the general sensitivity of the area to even gentle manipulation. It is therefore beneficial that an attachment be placed at surgery to maintain the treatment momentum.

Speed of Eruption

When traction is applied to a palatally impacted canine in the closed eruption technique, the tooth may move rapidly and create a very palpable bulge beneath the thick mucosa of the palate, but will often experience difficulty in erupting through it. In these circumstances, it is recommended that a small circular incision be made around the crown tip of the impacted tooth and the tissue removed, to re-expose the tooth to a level not exceeding the greatest circumference of its crown. Further traction will then erupt the tooth very rapidly. Delay in performing this simple procedure will simply cause the anchor teeth to intrude and the overall arch form to become disrupted.

The Final Treatment Outcome

Over the years, several groups of researchers in a number of countries have studied the post-treatment pulpal and periodontal status following the orthodontic resolution of impacted teeth, particularly in relation to maxillary canines and the open exposure technique. A Norwegian group [28] found an increased depth of periodontal pockets on the distal of the impacted teeth and bone loss on the mesial. In a group of patients with impacted canines, treated by undefined ‘conservative’ surgical procedures, a Seattle group [29] found attachment loss, reduced alveolar bone height and frequent instances of pulp obliteration, discoloration and misalignme/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses