Chapter 3

Radiology and the Dental Emergency Clinic

Introduction

X-ray examination is an important tool that helps clinicians to diagnose, plan and monitor both treatment and lesion development. In the United Kingdom, dental radiographs account for approximately one-third of all diagnostic radiological examinations, which emphasises their value in virtually all areas of dental work.

X-rays are part of the electromagnetic spectrum with a high energy and ability to cause ionisation and damage to living tissue. Low-dose damage is cumulative and adverse effects can take decades to become manifest but include the potential development of malignancy. As a consequence, X-rays need to be used prudently. Their use is controlled by specific legislation, which in the United Kingdom includes the Ionising Radiations Regulations 1999 (IRR99) and the Ionising Radiations (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000 (IR (ME) R2000). Details of these regulations will not be given here but are based on three core concepts of radiation protection: justification, optimisation and limitation, which are discussed in the following sections.

Justification

The prescription of a radiograph must, in every case, be of some positive benefit to the patient and influence their treatment. The clinician should be sure that the information required is not already available on an existing film or obtainable using any other means. In the dental emergency clinic, this can cause significant inconvenience but the basic principle should be remembered.

Optimisation

Where the decision has been made to request a radiograph, the dose must be kept ‘as low as reasonably practicable’. This can be achieved by using appropriate equipment, good technique and by having a quality control programme in place to ensure films are consistently of diagnostic quality.

Limitation

Limitation incorporates the concepts of justification and optimisation and also that all X-ray equipment is operating within accepted dose limits. It is important that X-ray equipment is subject to formal acceptance testing, routine quality control, undergoes proper maintenance and has all the standard dose reduction features present.

An essential aspect of justification for any radiographic examination is that such examination should not be undertaken until after a clinical history and examination has been performed. The concept of ‘routine’ or ‘screening’ radiographs should be avoided. Guidelines on the appropriate use of radiographs in dental practice, such as those produced by the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners of the Royal College of Surgeons of England should be followed.

It should be remembered that children are more susceptible to the damaging effects of ionising radiation and consequently their use should be even more circumspect.

There are basically four types of dental radiological procedure:

1. Intra-oral (bitewing, periapical and occlusal) radiography

2. Panoramic radiography (DPT)

3. Cephalometric radiography

4. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT)

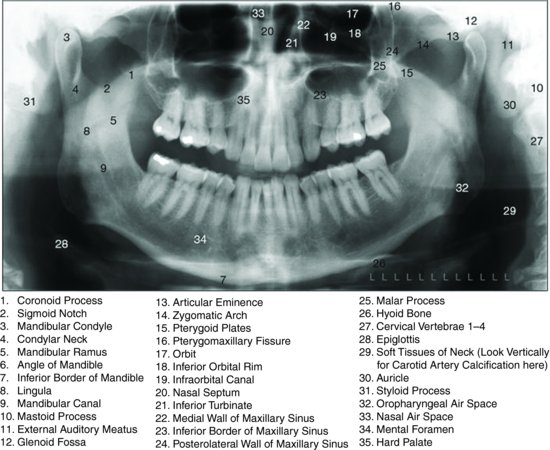

Figure 3.1 shows a panoramic radiograph and is labelled to show the features. Generally, where detail is required, such as for the assessment of dental caries, periapical pathology, periodontal assessment or root fractures, intra-oral views are the most useful, whereas if the examination requirement extends beyond purely the dento-alveolar region, extra-oral imaging may be more appropriate. However, extra-oral views have a higher radiation dose.

Figure 3.1 A panoramic radiograph demonstrating the anatomy that can be imaged.

The increasing use of digital sensors in dental radiography does result in a lowering of dose, particularly for intra-oral radiographs, and also gives the facility for computer manipulation of the images as well as enhancing their diagnostic usefulness. Typical effective doses in dental radiography are shown in Box 3.1.

Box 3.1 Effective doses in dental radiography

- Intra-oral dental X-ray imaging procedure 1–8 μSv

- Panoramic examinations 4–30 μSv

- Cephalometric examinations 2–3 μSv

- Cone beam computed tomography procedures 34–652 μSv (for small dento-alveolar volumes) and 30–1079 μSv (for large ‘cranio-facial’ volumes)

- Natural background radiation 2–8 mSv/year

(μSv = microsievert)

Cone-beam computed tomography

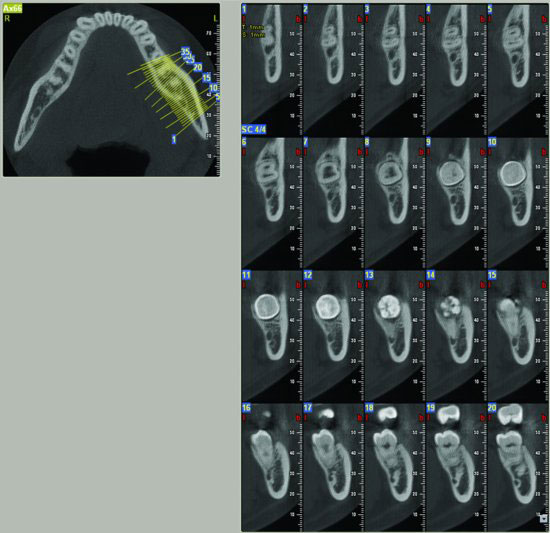

CBCT offers the dental surgeon a new way to image their patients in axial, coronal and sagittal planes with three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions as well as in variable panoramic slices. The full potential of this technique is still to be fully realised. An example of a CBCT image is shown in Figure 3.2 demonstrating the detail provided. As equipment becomes more common and affordable, the number of clinical situations when CBCT may be used will increase but it should be remembered that the dose is considerably higher than for other dental imaging modalities. Views such as intra-orals may still be the most appropriate, however in many situations. In general, the following guide for CBCT can be considered.

Figure 3.2 Cone-beam computed tomographic image that shows the detail of anatomy, including its facility for cross-sectional imaging.

Factors to consider in the use of CBCT

The smallest volume compatible with the clinical situati/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses