Chapter 3 Photography

Digital and Analog

Section A Clinical Photography Standards

Relevance of Photography to Esthetic Dentistry

Equipment options

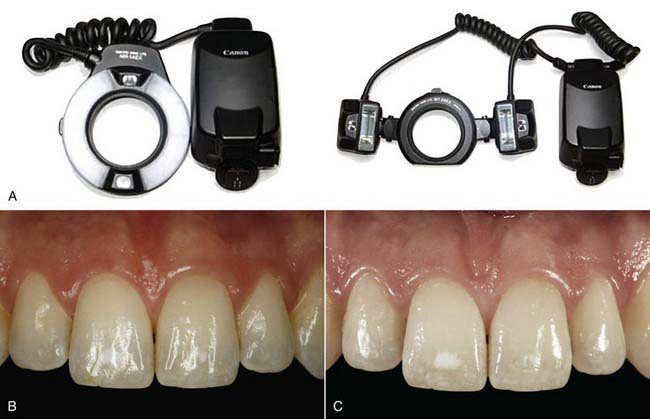

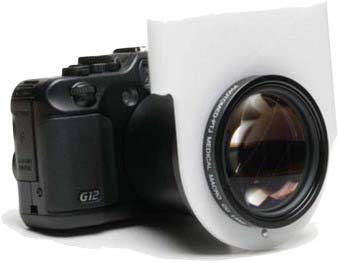

There are three levels of sophistication. Assuming that the 35-mm film camera is no longer in use, many dentists’ entry point into clinical photography is a modified “point-and-shoot” camera (Figure 3-1) or an entry-level digital SLR camera (Figure 3-2). For the dentist who wants to improve their clinical photography, there is more sophisticated equipment that allows better images and greater clinical latitude.

FIGURE 3-1 A typical “point-and-shoot” setup.

(Courtesy PhotoMed International, Van Nuys, California.)

FIGURE 3-2 A typical single-lens reflex (SLR) setup.

(Courtesy PhotoMed International, Van Nuys, California.)

Current Best Approach

In addition to the body and the lens, a flash is required. In order to achieve images with all the teeth in sharp focus, the shutter speed is set to a fraction of a second to eliminate camera shake, the aperture is set to a very small opening size to maximize depth of field, and thus there is a need for an additional light source as ambient light will be far from sufficient. The most straightforward option for most practitioners is a ring flash. For a few practitioners who are very interested in taking the absolutely best-quality clinical pictures possible, more sophisticated flashes are available (Figure 3-3). These include a dual point flash, a twin light source that allows the alteration of the illuminations to show line angles and translucencies on teeth and restorations more accurately. This permits one to have more control over the final image. However, the requirement to adjust the flash heads individually for each shot makes it impractical for many dentists.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses