These interferences, which may be of many types and may occur at any stage, may have repercussions on other anatomic structures (skeletal, dentoalveolar, temporomandibular joint-related, or postural), esthetics, or the psychological well-being of the child.

There are three general categories of interference: mechanical, functional, and psychological (Gugino and Duss 2000). This chapter will discuss only the first two.

Interferences associated with malpositioned maxillary teeth—the functional guidance arch—precipitate compensatory reactions in the mandibular arch. This tends to lock the mandible into positions that limit its capacity to complete excursive movements, limiting mastication to primarily vertical activity.

Mechanical interference can be dental or skeletal in origin, can occur in the maxilla or in the mandible, and can operate in all three dimensions of space.

Transverse

Transverse interference is common (Figs 3-1 and 3-2).

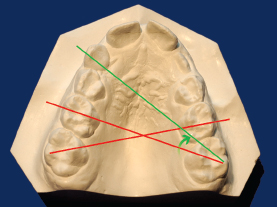

Fig 3-1a A V-shaped maxillary arch with mesial rotation of the permanent first molars, which occurs, according to Cetlin (1983), in 80% of patients, can cause premature contacts and interfere with lateral excursion. When a molar is rotated mesially, it occupies 12.0 mm of space instead of the normal 10.0 mm. Simply by correcting these rotations, the orthodontist can often obtain the space required to eliminate minor Class II malocclusions, while, at the same time, freeing the mandible from constraints. When molars are correctly positioned, a line connecting the distobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar with its mesiopalatal cusp should, when continued, pass across the distal third of the contralateral canine tooth (green line). Molars can be rotated mesially, as shown in the figure (red lines), or distally.

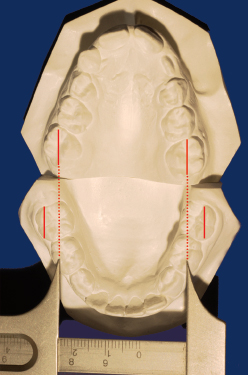

Fig 3-1b A V-shaped maxillary arch forces the mandible to position itself posteriorly to adapt to the reduced transverse maxillary dimensions. In this instance, the mandibular transverse dimensions are normal. The distance registered by the caliper corresponds to the maxillary intermolar distance, revealing how much smaller it is than the mandibular intermolar distance.

Fig 3-2b Premature contact of the primary right canines in centric relation provokes a lateral mandibular deviation.

Vertical

Anterior overbites, whether they result from alveolar discrepancies or skeletal ones, such as severe rotation during anterior growth, and open bites can both interfere with vertical mandibular movement (Figs 3-3 and 3-4).

Fig 3-3 In serious cases of deep bite, including all Class II division 2 malocclusions, the palatal inclination of the maxillary incisors interferes with anterior movement of the mandible and forces it posteriorly. Because the incisal palatal guidance is vertical, the mandible can escape this constraint only by opening downward and backward, a nonphysiologic movement. To accomplish this movement, the muscles that retract and lower the mandible are called into play; muscular harmony is altered, as are the pressures exerted by the condyles on the temporomandibular joint and, consequently, growth equilibrium. The posterosuperior pressure on the retrodiscal tissues of the temporomandibular joint provokes, through reflex action, tension on the pterygoid disc muscle, which pulls the disc forward as the condyle is pushed backward. In this situation, discal subluxation is frequent. During the course of growth in patients with overbite, incisors erupt along the line of their axial inclination, while maxillary molars descend along the facial axis, downward and forward (see chapter 4). In this type of growth, the distance between incisors and molars is diminished, the mandible is put at increasingly greater risk of being locked lingually, and the possibility of impaired eruption of the maxillary canines is increased. These observations indicate the importance of early intervention to unlock the mandible.

Sagittal interferences result from anterior overjet, linguoversion of the maxillary incisors, anterior crossbite, and molar prematurities or other occlusal interferences with lateral or protrusive excursive movements (Figs 3-5 and 3-6).

Functi/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses