Chapter 3

Management of Discoloured Dead Anterior Teeth

Aim

To consider relevant terminology and the methods of dealing with dead discoloured teeth, to describe the inside/outside bleaching technique in detail, and to consider alternative techniques and how to manage problems.

Outcome

The practitioner will be aware of predictable approaches to bleaching discoloured, dead anterior teeth and that bleaching is the most effective way of managing these teeth. The practitioner needs to be conscious of the destructive nature of alternative interventive treatments.

Discoloured Dead Teeth

Dentists often refer to dead teeth as non-vital teeth, and patients are frequently bemused by this. This is a good example of not using plain English! To most people the word vital means essential. In dental terms non-vital describes a tooth that has a dead pulp or has had the pulp removed as part of an endodontic procedure.

Patients with a low lip line may well accept a mildly discoloured dead front tooth while those with a high lip line may very well find any discolouration unacceptable. Such discolouration is often the reason for seeking treatment.

Improving the appearance of a discoloured dead front tooth can have a profound effect on the patient’s self-confidence and oral health. Such thinking has been recognised by the World Health Organization, which has stated that “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (1994). Marked discolouration of teeth can be a serious handicap which impacts on a person’s self-image, self-confidence, physical attractiveness and employability.

Assessment

The successful management of discoloured dead teeth is based on an accurate diagnosis followed by detailed treatment planning. A comprehensive history should be taken, including details of events that may have contributed to the discolouration. A detailed clinical examination, including special investigations as indicated clinically, should then follow.

A focused approach will reduce the chances of overlooking critical information and avoid failure of treatment. Patient input is critical. A full and frank discussion of a patient’s perceptions of their problem is especially important in assessing whether or not they have realistic expectations of the outcome of treatment. Whatever treatment plan is agreed, it should provide the best possible prospects for a durable, predictable, aesthetically pleasing and cost-effective result for the patient. This should be accomplished with the least possible biological damage.

Aetiology

The most common cause of discolouration in dead teeth is the presence of residual pulpal haemorrhagic products. These are most likely to be left in the pulp horn spaces and cervical region. The discolouration is usually caused by breakdown products of haemoglobin and other haematin molecules, which may permeate into the dentine of the dead tooth.

Trauma is the most common cause of dead front teeth. Patients may not give a clear history of the relevant trauma. They may have been under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time or they may have been more concerned about other injuries and therefore overlooked the trauma to their teeth. The discolouration, which may be gradual, is often painless and may only become apparent when others comment on it. Discolouration of a dead tooth may be an incidental finding in a routine dental examination.

Discolouration often follows endodontic treatment of a tooth. Indeed, many patients on being told that they need a root filling ask if their tooth will turn black afterwards as a consequence of this.

About 10% of patients may be unhappy with the appearance of their root-filled teeth. Incorporating blood or other stain into the tooth/restoration interface may cause, or substantially contribute to, discolouration. Materials used in endodontic procedures, including root canal sealants containing silver, eugenol, polyantibiotic pastes, and compounds containing phenol, may cause darkening of the root dentine. Metallic points, pins and posts inserted into dead teeth are a frequent cause of discolouration. In addition, leakage of restorations may be a causative or contributing factor. Sadly, much of the discolouration seen in endodontically treated teeth can be described as iatrogenic. Figs 3-1 and 3-2 show upper incisors before and after bleaching.

Fig 3-1 Discoloured upper incisors before bleaching.

Fig 3-2 Upper incisors after bleaching.

Mechanisms of Discolouration

When teeth suffer significant trauma there is disruption of the pulp contents and vascularity. This can result in haemorrhage and subsequent tooth discolouration. The extent to which the products of pulp degradation contribute to tooth discolouration remains unclear. It is considered that pulpal ischaemia and subsequent pulp death, in the absence of bacterial contamination, does not produce discolouration to the same extent as overt haemorrhage into the pulp chamber. Following haemorrhage, the haemoglobin molecules may be found to be concentrated mainly in the coronal dentine close to the pulp. They do not tend to penetrate far into the dentinal tubules. This largely explains why inside/outside bleaching produces predictably satisfactory results.

In traumatised teeth marked changes in colour appear to occur only when there has been frank haemorrhage into the pulp chamber. The coloured pigment responsible for the discolouration arises from the haemoglobin in the red blood cells. The cementum layer appears to act as a barrier to the passage of the blood pigments, preventing root surfaces from being discoloured by blood from bleeding of the soft tissues.

Any methods attempting to remove discolouration following trauma and haemorrhage into the pulp chamber should focus on the removal of the breakdown products of blood. The pulp chamber is surrounded by dentine and isolated from any inflammatory or healing response in the adjacent soft tissues. Therefore, normal healing, which could occur for example with a black eye, with the eventual loss of discolouration in the tissues, cannot occur. If the pulp does not survive following trauma and haemorrhage then the haematin material remains within the pulp chamber and consequently the tooth appears discoloured. On the other hand, if revascularisation occurs and the pulp survives then the tooth can revert to its normal colour within two to three months.

Monitoring

The colour of teeth can be monitored by using a shade guide or by taking photographs with a shade tab beside the tooth. A record should be kept. Follow-up reviews of root canal treatment should include a check for discolouration using the shade guide or photograph as a reference. If discolouration is observed, it is better to intervene sooner rather than later. Later discolouration may indicate, among other possibilities, leakage or degradation of the endodontic sealer. Delaying treatment may well result in the discolouration being more difficult to treat.

Inside/outside Bleaching

Prior to undertaking inside/outside bleaching the tooth should be root-filled in a standard fashion, under rubber dam using copious amounts of hypochlorite. Hypochlorite is a bleach and although mainly used as an antiseptic it inadvertently also removes some of the discolouration. However, this is not nearly as effective as the carbamide peroxide used in inside/outside bleaching.

This technique involves placing 10% carbamide peroxide gel simultaneously on and inside a discoloured root-filled tooth, usually with the aid of a single-tooth customised tray. This allows penetration of hydrogen peroxide both internally and externally, with the bleaching gel being protected from salivary deactivation by the tray (see Figs 3-3 to 3-5).

Fig 3-3 Discoloured luxated extruded upper left incisor.

Fig 3-4 Single-tooth tray.

Fig 3-5 Occlusal view of single-tooth tray.

Access is gained to the pulp chamber via a standard access cavity (Fig 3-6, page 40). Prior to bleaching, the contents of the chamber should be removed and the chamber thoroughly cleaned for about five minutes with an ultrasonic tip (Fig 3-7). The root filling is reduced to a level below the cemento–enamel junction and is usually sealed off with a radiopaque glass ionomer or zinc polycarboxylate cement. It is technically difficult to place this cement seal accurately. It is essential, however, that the cement does not contact the discoloured dentinal walls because if it does this will compromise effective bleaching of the neck of the tooth.

Fig 3-6 Mirror view of upper left central incisor showing access cavity.

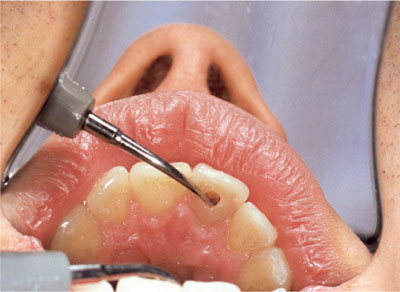

Fig 3-7 Ultrasonic cleaning of the chamber to below the cemento-enamel junction.

In cases of marked cervical discolouration it is possible to undertake bleaching without sealing over the root filling, provided patient cooperation is very good and the access cavity can be kept constantly bathed in 10% carbamide peroxide. Carbamide peroxide is a well-proven oxidising antiseptic and will inhibit Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria very effectively.

Any composite on the external or internal surfaces of the tooth must be removed before bleaching, as the hydrogen peroxide cannot penetrate through composite. The endodontic access cavity is left open for the duration of the inside/outside bleaching procedure, which usually takes two to four days.

The 10% carbamide peroxide gel, both within the tooth and in the tray, is changed every two hours and last thing at night. The more often the gel is changed, the quicker bleaching will occur.

The tray is worn continuously, except during eating, cleaning and replacing the gel. When changing the gel, and in particular after eating, the access cavity is flushed out using a syringe of the gel. Because of its viscous nature this syringing effect removes any food debris and ensures that the cavity is filled with fresh gel. The patient will not experience sensitivity because the tooth is root-filled.

The patient is instructed to stop bleaching when they are satisfied with the degree of lightening of the tooth. It is acceptable for the tooth to go a little lighter to allow for “rebound” of the colour. The patient is reviewed after two to three days to assess colour changes and to limit the time the access cavity is left open (see Figs 3-6 to 3-13).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses