3

How Two Young Dentists Changed the History of Surgery

Horace Wells (1815–1848) and William Thomas Green Morton (1819–1868)

The necessity for speed in surgery, due to the inability to control bleeding, limited its quality. In order to amputate a limb, as was frequently necessary for war casualties, the patient would be tied down and/or physically restrained by two or three assistants and given a wooden block to bite on. A stiff drink was known to help somewhat at operations, although the large doses required to have any effect were likely to cause vomiting instead of a drunken stupor. A less scientific method occasionally used consisted of a knockout punch to the jaw (as long as any resulting fracture caused less hurt than the operation). In similar fashion, the patient’s head was occasionally protected with a helmet, after which a strong blow was struck on it with a wooden hammer!

With the patient inevitably awake and terrified, the surgeon would begin the amputation. The skin and muscle would be cut to expose the bone, which would then be sawn off (generally within about a minute): the wound might then have been cauterised with a red-hot poker or had boiling oil poured into it in the hope of stemming post-operative bleeding. The patient would be fortunate to faint during the procedure. The only certainty along with the excruciating pain was a high death rate. Surgeons of yesteryear must have had very strong constitutions, especially as they did not have the same standing as physicians. It is against this background that two young American dentists, Horace Wells and William Thomas Green Morton, enter the story.

Horace Wells

Horace Wells (Figure 3.1) was born in January 1815 in Hartford, Vermont. He lived in a farming community, receiving a good education at local schools. He moved to Boston at age 19 and chose a career in dentistry. Although some dentists were educated at that time, occasionally even obtaining a medical degree, the majority had no formal qualifications. The reputation of dentists was low, especially compared with doctors. Dentistry was carried out mainly by quacks and charlatans so that, wherever possible, people avoided treatment. Learning the practical skills meant becoming apprenticed to a dentist, observing and assisting. However, improvements for better training were under way with the opening of the first dental college in Baltimore in 1840.

Figure 3.1 Portrait of Dr Horace Wells.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wells_Horace.jpg. This media file is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to 1 January 1923.

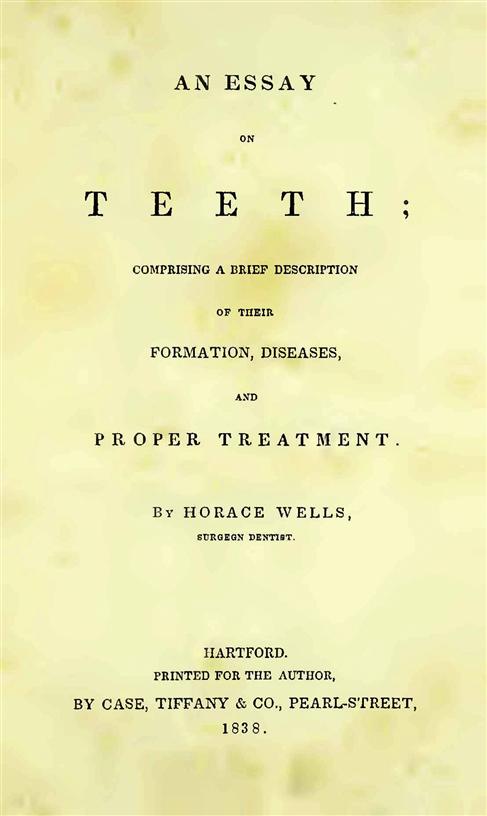

Following a 2-year apprenticeship, Wells opened his own dental practice in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1836: he was 21 years old. At that time, dentistry consisted mainly of extracting teeth, plugging large cavities and providing false teeth. Unlike many in his profession at the time, Wells was an intelligent, enquiring, conscientious and innovative practitioner. In 1838, he published a small pamphlet entitled ‘An essay on teeth, comprising a brief description of their formation, diseases and proper treatment (Figure 3.2). In this 70-page essay, the young Wells considers some of the important clinical aspects of dentistry. He reveals himself as mature, well-read and literate, with a considerable mastery of his subject. He displays a sharp mind and evidence of a critical, scientific approach. He scolds the great John Hunter (see Chapter 12) for suggesting the teeth do not have a circulation (viable dental pulp), commenting that ‘Mr Hunter was not a practical Dentist: but a very able Surgeon, and writer: had he attended to the practical part of Dental Surgery, it is not improbable that his opinion on this subject would have met with a material change’. In discussing the causes of tooth decay, he makes the following perceptive statement: ‘A simple diet is the surest preventive of disease in the teeth which can be recommended. Sumptuous fare might not act as a direct cause of caries, but it most assuredly has its influence through other agents. If this statement requires proof, we need but look among our savage tribes, who live on coarse fare, and never experience the many infirmities to which we are subject; but pass along to old age with good health, never requiring the aid of a dentist’.

Figure 3.2 Front piece of the 1838 pamphlet produced by Horace Wells.

Source: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Wells soon developed a successful practice and was respected both within the community and among his fellow dentists. However, an aspect of dentistry that must have caused him feelings of inadequacy was tooth extraction, one of the mainstays of any dental practice. The extreme pain of toothache would delay people seeking treatment until the very last minute, knowing how painful the procedure of extraction would be. All that Wells could suggest to his patients in order to mitigate the pain would be to swig some alcohol beforehand, give them some laudanum (tincture of opium), or, occasionally, some morphine. Speed, strength and a sure technique would have been useful assets for a successful dentist. Imagine needing more than one tooth extracted at the same time! Wells must have been concerned about the suffering and would have been looking for anything that might alleviate the pain.

With such a busy practice, Wells was soon in a position to employ an apprentice and, in 1842, took on William Thomas Green Morton (Figure 3.3). Born in August 1819 in Charlton, Massachusetts, he was 4 years younger than Wells. Morton left school at 16 years with relatively little education. Having already been unsuccessful in a number of different (and shady) enterprises, he embarked upon a career in dentistry. In associating with Wells, Morton was fortunate to become apprenticed to a man with a growing professional reputation.

Figure 3.3 Portrait of William Thomas Green Morton, 1868.

Source: Posted by R. Cusari 2006. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:WilliamMorton.jpg. This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to Australia, the European Union and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years.

As these two young men would be quietly working away in their small, provincial dental practice, it seems inconceivable to think that they, in preference to all the eminent scientific and medical minds of the time, would be responsible for one of the greatest medical advances in history.

By 1843, the enterprising Wells had developed a new technique whereby he could successfully solder false teeth onto a denture without any subsequent corrosion. As was common at the time, he sought an endorsement of his discovery from a prominent scientist and chose Dr Charles Thomas Jackson (Figure 3.4). Jackson agreed to allow his name to be used in endorsing this product. In the latter part of 1843, Wells and Morton formed a partnership to use this new product, and both were confident that it could make their fortunes. To this purpose, they opened a new practice in Boston.

Figure 3.4 Portrait of Dr Charles Thomas Jackson. Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jackson_Charles_Thomas.jpg. This media file is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to 1 January 1923.

Unfortunately, the partnership did not immediately bring in the economic rewards expected and was dissolved within a few weeks. There may have been personality clashes; but whatever the cause, the eventual result was that Wells returned to Hartford while Morton stayed on in Boston.

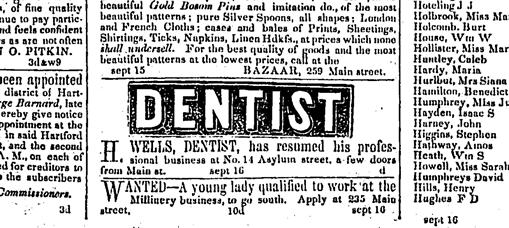

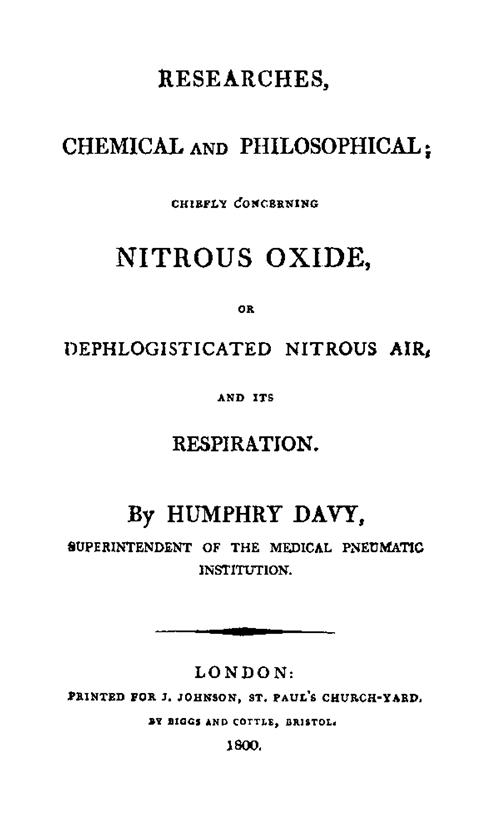

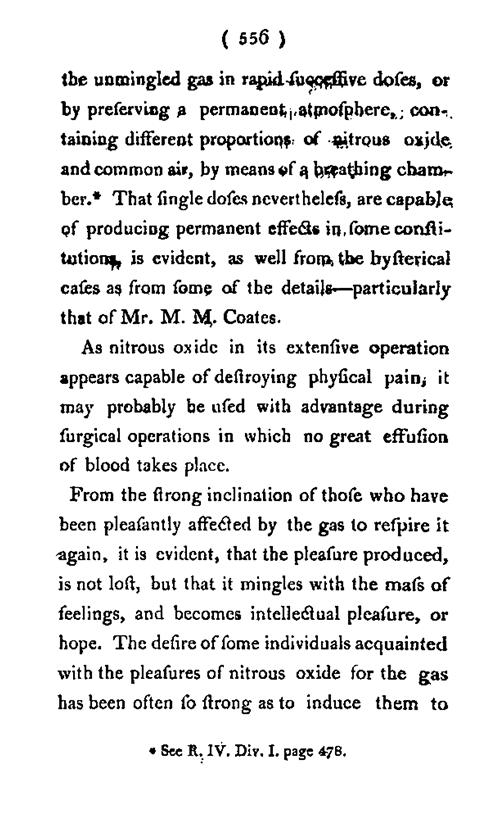

Wells announced his return in the Hartford Courant (Figure 3.5) and there re-established his dental practice. A form of entertainment popular at the time consisted of shows featuring ‘laughing gas’. Laughing gas was the common name for nitrous oxide, which had first been identified by the English chemist Joseph Priestly in 1772. In 1800, another Englishman, Sir Humphry Davy, described numerous detailed experiments in which he himself inhaled the gas in varying quantities and for varying amounts of time. He also described the reactions of friends who volunteered to inhale the gas, including the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the potter Josiah Wedgewood. Davy discovered that inhaling the gas aroused him to an excitable state, sometimes leading to uncontrollable laughter, but the effects quickly wore off. For this reason, Davy called nitrous oxide laughing gas. He also wrote with great prescience that, as the gas ‘appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place’ (Figures 3.6 and 3.7). However, these perceptive comments were not followed up for another 50 years.

Figure 3.5 Advert in Hartford Courant advising of Wells’s return and reestablishing his dental practice. It states ‘H. Wells, dentist, has resumed his professional business at no 14 Asylum Street, a few doors from Main St. September 16’.

Source: Courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress.

Figure 3.6 Front piece to Humphry Davy’s book on nitrous oxide published in 1800.

Figure 3.7 Middle paragraph on page 556 from Sir Humphry Davy’s book seen in Figure 5. Stating ‘As nitrous oxide in its extensive operation appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place.

At laughing gas entertainments, an entrance fee would be charged and the showman would give an introductory lecture on the properties of the gas. This would then be followed by practical demonstrations when volunteers from the audience would come up on stage and inhale through the mouth from bags containing the gas, while their nostrils were pinched together. When the volunteers had inhaled enough gas, it would give them a feeling of exhilaration and intoxication, leading them to carry out amusing, involuntary antics, such as running around, fighting, bumping into objects and laughing. There were no unpleasant aftereffects as the gas rapidly wore off. The volunteers would have no recollection of their embarrassing on-stage behaviour, much to the amusement of their friends and onlookers.

On 10 December 1844, Wells attended one of these popular shows when the gas was administered by ‘Professor’ Gardner Quincy Colton, who himself had studied medicine. Wells was an eager volunteer to inhale the gas. Amidst all the escapades carried out on stage, he noticed that one of the participants, who afterwards sat down beside him, had gashed his knee badly while under the influence of the nitrous oxide and yet had no recollection of any pain. Wells immediately had the inspired thought that perhaps teeth could be extracted without pain using the laughing gas.

That same evening he discussed the idea with his colleague and friend John Riggs, who ran a dental practice nearby. They concluded that such a procedure would necessitate taking a patient beyond the light, excitatory stage seen at shows, to a deeper level leading to loss of consciousness. They did not have any knowledge of either the chemical properties or the biological properties of nitrous oxide, but they were aware that there was a risk of danger and even death. Wells had a troublesome upper wisdom tooth (third molar) that needed extracting, and so he bravely (or recklessly!) volunteered to be the first patient.

The following morning, 11 December, Wells went to his surgery to meet Riggs, whose support was noteworthy, because if anything untoward happened, Riggs was likely to receive some very unfavourable publicity. Colton was on hand to provide a bag of nitrous oxide which Wells held while inhaling from it. Wells soon drifted into a state of unconsciousness, at which time Riggs stepped forward and swiftly extracted the tooth. Recovering rapidly from the anaesthesia, Wells declared he had experienced absolutely no pain. That simple experiment is regarded as one of the great moments in medicine: the first, successful, pain-free operation.

Over the next few days, Wells used nitrous oxide to extract teeth without pain in about 15 patients, generally, but not always, meeting with success. Colton taught him how to prepare and administer the nitrous oxide gas. Hearing about this procedure, local doctors also used the gas for one or two minor surgical operations, with Wells administering the anaesthetic. Wells told others, including Morton and Jackson, of his new discovery.

As Wells believed that an important sign of the anaesthetic effect was its excitatory properties in low concentrations, there is some evidence that he did try using ether, which also had an excitatory phase. In discussing the pros an/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses