Chapter 3

Gingival Colour Changes – Localised

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe those gingival colour changes that are localised in one area or, in some cases, several discrete areas of the gingivae.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the reader should have an increased awareness of the nature of local gingival colour changes, their clinical significance and appropriate management, including differential diagnosis and treatment if indicated. The contents of this chapter are summarised in Table 3-1.

| Major Categories | Sub Categories | Frequency of Condition | Management Setting |

| Red lesions | Kaposi’s sarcoma | Rare | Specialist referral for diagnostic confirmation and investigation of immune status |

| Arteriovenous malformations/ haemangiomata | Uncommon | Many lesions require no active intervention other than reassurance | |

| Telangiectasia | Uncommon | No active intervention required but may need to investigate for underlying disease – best undertaken in specialist units | |

| Erythroplakia | Very rare | A sinister lesion. Urgent referral to secondary care for diagnosis and appropriate treatment | |

| White lesions | Trauma | Common | Primary care |

| Leukoplakia | Uncommon on the gingivae | Biopsy and monitoring can be undertaken in primary care. More extensive lesions should be managed in specialist units | |

| White sponge naevus | Rare | Diagnosis will usually be the remit of specialist units. No active treatment is required and there is no known malignant potential | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Very uncommon on the gingivae | Urgent referral to specialist units | |

| Lichen planus | Common | Recalcitrant lichen planus should be referred to specialist units for diagnostic confirmation, treatment and monitoring | |

| Candidosis | Gingival involvement is very rare | Referral to specialist units for further investigations | |

| Pigmented lesions | Amalgam tattoo | Common | Primary care or referral if diagnosis is in doubt |

| Melanotic macule | Uncommon | Primary care or referral if diagnosis is in doubt | |

| Naevi | Uncommon | Primary care or referral if diagnosis is in doubt | |

| Malignant melanoma | Very rare | Urgent referral to specialist unit |

Red Lesions

It is important to consider that some localised red lesions may represent periodontal sepsis, for example a lateral periodontal abscess, but this will be discussed in Chapter 5.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma occurs in more than 50% of patients with AIDS, becoming increasingly frequent as the disease progresses. Oral involvement may be the initial site of presentation, and gingival involvement is common. This condition may present as an epulis, perhaps mimicking a vascular pyogenic granuloma.

Clinical appearance

-

Clinical appearance is variable, light (Fig 3-1), dark red (Fig 3-2), purple/blue or even de-pigmented lesions having been described.

-

Sessile macules/papules which may also have a nodular surface and become exophytic.

-

Satellite lesions may develop.

Fig 3-1 Kaposi’s sarcoma that is pale in appearance.

Fig 3-2 Kaposi’s sarcoma that is dark red in appearance.

Clinical symptoms

-

Usually asymptomatic but patients may complain about the aesthetics or of bleeding following trauma.

Aetiology

-

Human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) – a gamma herpes virus is strongly associated with the aetiology of KS.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

-

The palate is the most common site of intra-oral involvement, particularly following the course of the greater palatine neurovascular bundles (Fig 3-3).

-

Skin lesions.

-

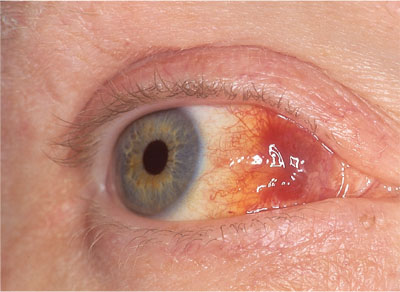

Ocular lesions (Fig 3-4).

-

Visceral involvement.

Fig 3-3 Kaposi’s following the greater palatine neurovascular bundle.

Fig 3-4 Ocular involvement of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Differential diagnosis

-

Haemangiomata/Arterio-venous malformations.

-

Inflammatory hyperplasias, e.g. pyogenic granuloma or peripheral giant cell lesions.

-

Periodontal abscess.

-

Localised plasma cell gingivitis.

-

Localised lesions of Molluscum contageosum.

-

Pigmented lesions including malignant melanoma.

-

Bacillary angiomatosis (secondary to Bartonella henselae/quintana infection).

Clinical investigation

-

Definitive diagnosis is by incisional biopsy, though lesions can appear benign and histologically identical to a pyogenic granuloma.

-

Careful medical and sexual histories are crucial to aid presumptive diagnosis.

-

In-situ polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used, where available, to identify HHV8 within the tumours.

Management options

-

Lesions are often multifocal, and thus further medical examination is necessary to identify the distribution of all lesions.

-

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) may affect resolution of the lesions.

-

Chemotherapy.

-

In early lesions local management may be indicated, (e.g. intralesional vincristine, surgical excision).

Vascular Lesions

Clinical features

-

Vascular lesions that affect the gingivae are an uncommon clinical finding.

-

Colour varies from blue/red/purple.

-

They may be flat or more commonly elevated.

-

Usually asymptomatic.

-

Blanching occurs on pressure as the vessels are emptied.

-

Occasionally they may bleed, eg if traumatised.

Aetiology

-

Haemangiomata – developmental lesions that are present from birth and spontaneously regress with age (Fig 3-5).

-

Arterio-venous malformations (Fig 3-6).

Fig 3-5 Haemangioma.

Fig 3-6 Arterio-venous malformation.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

-

Tongue.

-

Lip.

-

Any area can be involved, intra-orally or extra-orally.

Differential diagnosis

-

Telangiectasia.

-

Purpura.

-

Kaposi’s sarcoma.

-

Lymphangioma.

Clinical investigation

-

Aspiration.

-

Imaging to identify extent and distribution of the lesion (MRI, Doppler ultrasound).

-

Angiography.

Management options

-

Usually require no active treatment.

-

Cryosurgery (Fig 3-7).

-

Laser.

-

Sclerosing solutions.

-

Embolisation of feeder vasculature.

Fig 3-7 Cryosurgery to an arteriovenous malformation.

Telangiectasia

Telangiectasia, are capillary blood vessel dilatations and may occur peri-orally and intra-orally. They are uncommon on the gingival tissues (Fig 3-8).

Fig 3-8 Perioral and lingual telangiectasia in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis.

Clinical appearance

-

Small red macules, often multiple, which blanch on pressure.

Clinical symptoms

-

Telangiectasia are usually asymptomatic but may bleed on trauma.

Aetiology

-

Congenital or developmental depending on the type.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

-

Telangiectasia may occur on any skin or mucosal surface as well as involving the viscera.

Differential diagnosis

-

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome)

-

Cutaneous and gastrointestinal tract involvement is common.

-

Epistaxis is also a frequent accompanying feature.

-

-

Limited systemic sclerosis (previously known as ‘CREST’ syndrome – an acronym for: Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophagitis, Sclerodactyly and Telangiectasia). See Chapter 10.

Clinical investigation

-

The diagnosis is usually made on clinical history and examination.

Management options

-

No active intervention is usually indicated.

Erythroplakia (Erythroplasia)

Clinical features (Reichart 2005)

-

A rare lesion.

-

Appears as an atrophic, flat velvety red patch. (Fig 3-9)

-

Very high incidence of dysplasia or frank malignancy – erythroplakia should be regarded as malignant until histologically proven otherwise.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses