Differential diagnosis by site

Keypoints

Cervical lymph node disease

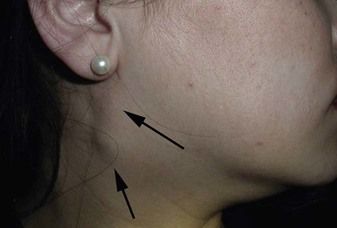

Cervical lymph nodes must be examined in every patient. Though most causes of enlargement (lymphadenopathy) are inflammatory (lymphadenitis), especially arising from local infection; others may be caused by malignant disease (Figure 3.1) – either local, distant or systemic – or other serious causes.

Infection (the usual cause) may be:

Other inflammatory causes may be:

Drugs – particularly phenytoin – may also be a cause.

Causes may include:

local viral (e.g. herpes simplex infections) or bacterial (dental, scalp, ear, nose or throat) – including cat-scratch fever, staphylococcal lymphadenitis and cervicofacial actinomycosis (Figure 3.2)

local viral (e.g. herpes simplex infections) or bacterial (dental, scalp, ear, nose or throat) – including cat-scratch fever, staphylococcal lymphadenitis and cervicofacial actinomycosis (Figure 3.2)

Salivary gland disease

Keypoints

Causes may include:

Acute bacterial (ascending) sialadenitis

Rare, except when following hyposalivation.

Mucocele

Mumps (acute viral sialadenitis)

This is more common in childhood if vaccination with MMR (mumps, measles and rubella vaccine) is not taken.

Salivary gland neoplasms

These are uncommon. Classification of the most common salivary neoplasms is:

Neoplasms in major salivary glands

Intraoral (minor) salivary gland neoplasms

Sarcoidosis

Uncommon granulomatous condition.

Sialosis

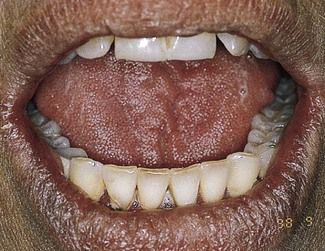

Sjögren syndrome

Uncommon, the cause is unknown but it is immunological and possibly viral. The common features are dry mouth and dry eyes: joint and other problems may be associated.

Most of these lymphomas are relatively low-grade and require either no treatment apart from regular follow-up or low-dose chemotherapy.

dry mouth:

dry mouth:

IgG4 syndrome

IgG4 syndrome (‘IgG4 related systemic sclerosing disease’, ‘IgG4-related autoimmune disease’, ‘IgG4-related systemic disease’, ‘IgG4-positive multiorgan lymphoproliferative syndrome’) often manifests with enlarged salivary glands (previously called Mikulicz disease or Kuttner tumour [sclerosing sialadenitis]) and one-third also suffer from dry eyes and dry mouth and arthralgias, so for many years this was considered a subgroup of Sjögren syndrome.

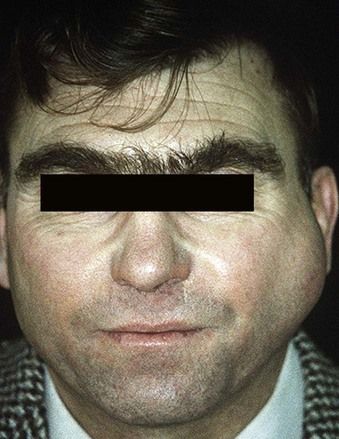

IgG4 syndrome affects mainly middle-aged men. Many other organs and tissues are also involved, including pancreas (the most commonly affected tissue), gall bladder, bile duct, retroperitoneum, kidneys, lung, prostate, lymph nodes, breast, and thyroid and pituitary glands.

Patients have neither anti-Ro/SS-A nor anti-La/SS-B autoantibodies but they have low titres of rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear autoantibodies (ANA), and decreased serum complement. Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids or anti-CD20 therapy (rituximab).

Lip lesions

Keypoints

Actinic burns and cheilitis

Mainly seen in fair-skinned individuals exposed in sunny climes or at high altitude.

Allergic angioedema

Uncommon: mainly seen in those with allergic (atopic) tendency.

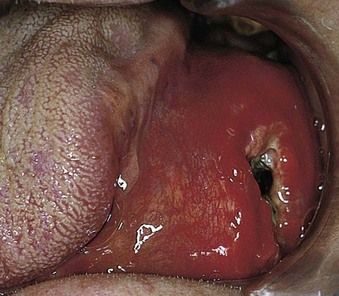

Angioma (haemangioma)

These are fairly common oral lesions.

Sturge–Weber syndrome (angioma that extends deeply and rarely involves the ipsilateral meninges, producing a facial angioma and seizure disorder, sometimes with learning impairment)

Sturge–Weber syndrome (angioma that extends deeply and rarely involves the ipsilateral meninges, producing a facial angioma and seizure disorder, sometimes with learning impairment)

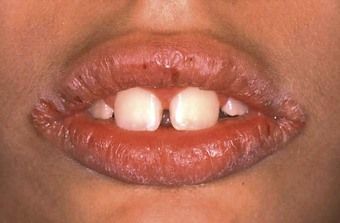

Carcinoma

Uncommon in England and Wales (600 cases/year) and declining: much more common nearer the Equator, especially in white-skinned people.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)

Rare. DLE may be categorized as:

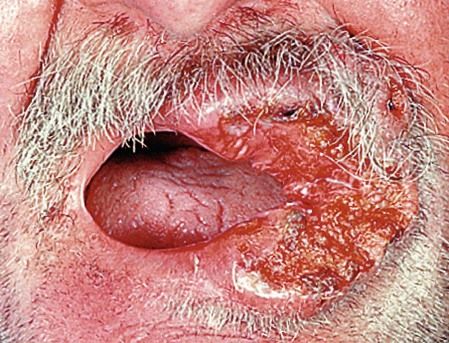

Erythema multiforme

Exfoliative cheilitis (factitious cheilitis, le tic de lèvres)

Hereditary angioedema

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses