Chapter 3

Children’s Behavior in the Dental Office

Jaap S.J. Veerkamp

This chapter discusses the reactions of children to dental treatment. It is intended to assist the dental health team in raising its perception of children’s behavior. The information will hopefully help dental professionals attain a greater sensitivity to the underlying factors which contribute to children’s reactions in the dental office. It is this kind of broad understanding that facilitates decisions concerning the management techniques that are likely to be successful for an individual child patient. Although clinical suggestions are offered on fostering positive reactions and dealing with negative ones, this is not the chapter’s main purpose: that information receives more attention in Chapter Six.

Historically, early writing on the subject of children’s behavior in the dental office began by following two lines of thought. First, a number of techniques for the “containment” of children in the dental environment were suggested. Second, the need for psychological knowledge and its application to children’s treatment was realized.

In the 1930s, the profession began to assess and detail children’s reactions to dentistry. There was an immediate interest in these writings which has been maintained and has steadily grown. The writings have taken two forms. The early descriptions were, for the most part, based on clinical observations and personal opinion. Collectively, these writings can be highly informative and useful in supporting theoretical guidelines. In the 1960s, controlled data-seeking investigations began to appear in the dental literature. As a result of differing viewpoints and experimental designs, the information gleaned from these studies can sometimes be confusing or contradictory. Nonetheless, they are helpful.

Guidelines are currently research-based. The focus is on evidence-based clinical trials (Roberts et al. 2010), which implies the use of randomized clinical trials (RCT). Since there has been a deficiency of this type of pediatric dentistry research over the past few decades, evidence often is gathered from other disciplines such as psychology or medicine (Klingberg 2008, Gustafsson et al. 2010).

The writings describing children’s behavior in the dental office have centered around three main areas. These areas include: (1) classifying children’s behavior, (2) describing various forms of behavior, wherein negative behavior patterns have been labeled and, (3) elaborating on factors which affect behavior in the dental environment. Hence, these main areas have served as natural focal points for the organization of this chapter.

Classifying Children’s Behavior

Numerous systems have been developed for classifying children’s behavior in the dental environment. The knowledge of these systems holds more than academic interest and can be an asset to clinicians in two ways: it can assist in evaluating the validity of current research, and it can provide a systematic means for recording patients’ behaviors. Interestingly, most classification systems that are used in clinical practice nowadays were spawned from research investigations.

When a clinician treats a child patient, the first issue of concern is the child’s behavior. The clinician has to classify the behavior (mentally at least) to help guide the management approach. There is wide variation between classification systems. One of the first was described by Wilson (1933), who listed four classes of behavior—normal or bold, bashful or timid, hysterical, and rebellious. During the same year, Sands wrote that children were of five types—hypersensitive or alert, nervous, fearful, physically unfit, and stubborn. These systems identified behaviors during dental procedures that mainly limited success of treatment. Nowadays, classification systems are often based on principles used in psychological questionnaires. Child behaviors during daily, non-dental situations may be placed into categories that summarize the personality of the child (Klaassen 2002). This provides information on the attitude of the child that is unrelated to treatment situations.

One of the most widely used systems was introduced by Frankl et al. in 1962. It is referred to as the Frankl Behavioral Rating Scale. The scale divides observed behavior into four categories, ranging from definitely positive to definitely negative. A detailed description of the scale is provided in Table 3-1.

The Frankl classification method, as seen in Table 3-1, is often considered the gold standard in clinical rating scales, mainly as a result of its wide usage and acceptance in pediatric dentistry research. Its popularity as a research tool has stemmed from three features. First, it is functional, as has been demonstrated through repeated usage. Second, it is quantifiable. Since it has four categorizations, numerical values can be assigned to the observed behavior. Finally, it is reliable. A high level of agreement among observers can be obtained. In fact, many investigations using this tool have shown the level of agreement to be 85% or higher—a very acceptable level in this type of research. These are the criteria for a measurement tool that are necessary for a successful investigation.

Table 3-1. The Frankl Behavior Rating Scale: A four-point scale with two degrees of positive behavior and two degrees of negative behavior.

| Categories of Behavior |

| Rating 1: Definitely negative Refusal of treatment, crying forcefully, fearfulness, or any other overt evidence of extreme negativism. Rating 2: Negative Reluctance to accept treatment, uncooperative behavior, some evidence of a negative attitude but not pronounced (i.e., sullen, withdrawn). Rating 3: Positive Acceptance of treatment, at times cautious, willingness to comply with the dentist, at times with reservation but follows the dentist’s directions cooperatively. Rating 4: Definitely positive Good rapport with the dentist, interested in the dental procedures, laughing and enjoying the situation. |

Other classification systems similar to the Frankl scale have been developed. Most notable are Likert-type scales, which have five levels of response (Rud and Kisling 1973). The studies of Venham et al. (1977) used the five-point scales to measure anxiety and behavior (self-report and proxy-report). Repeating their study, it was found that the two scales correlated so highly that the use of a single scale seemed appropriate (Veerkamp 1995). Other scales, such as the Houpt clinical rating scale (Houpt 1993) or the self-reporting Wong and Baker (1988) facial scale, are comparable systems. These are also useful in clinical settings, as well as research.

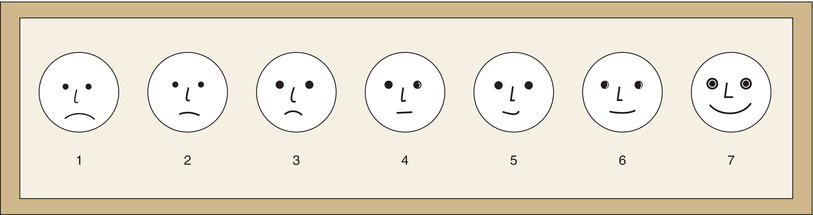

Self-report is the first method of choice when studying pain and/or anxiety. However, children under eight years of age have limited cognitive capacities: to depend on the accuracy of their reporting (ten Berge 2001) offers a greater risk of incorrect information. To improve the information on self-reporting rating scales for young children, some investigators have used small icons of dentistry-related situations or happy-to-sad faces as clinical endpoints (Venham et al. 1979; Wong and Baker, 1988, Chapman and Kirby-Turner, 2002). An example of such a scale is shown in Figure 3-1. In general, visual analogue scales (VAS) are the most effective with young children, with “very cooperative” and “uncooperative” as the clinical endpoints.

In her literature review, Aartman (1998) stated that the method of choice is to take two measurements, e.g., a self-report and an independent observer, and base conclusions on a combination of both reports. However, this approach may be impractical for some researchers and clinicians.

Classification procedures have important clinical application. Many general dentists have two thousand patients in their practices. If a fifth of these are children, the practice would contain four hundred child patients. It is impossible to recall how each child reacted during former visits. For pediatric dentists, having two thousand children in a practice and remembering their behaviors is even more daunting. Since the behavior of a child is an integral factor in the treatment planning, noting reactions can be of major assistance. Developing the habit of systematically recording patients’ behaviors on their clinical records takes little effort and can result in a big payoff.

Figure 3-1. A visual analogue scale using happy and sad faces as its endpoints. Chapman, H.R., Kirby-Turner, N. (2002). Visual/verbal analogue scales: examples of brief assessment methods to aid management of child and adult patients in clinical practice. British Dental Journal 193, 447–450.

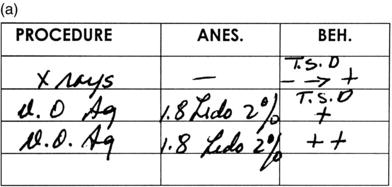

Figure 3-2. A section of a patient’s chart showing a child’s behavior recorded over a series of appointments (a). A separate column on the chart is reserved for this purpose. Notation of behavior should also be made in computerized patient charts (b). Courtesy of Elaine Schroit.

Knowledge of the progression of a child’s behavior during a series of appointments, or over a period of years, can assist in behavior management. It provides a base for planning. To gather this information, a separate column on the patient chart should be reserved for recording behavior. Figure 3-2 records a child’s behavior over several appointments using the Frankl Rating Scale. Note that the scale lends itself to a shorthand form. A child displaying positive cooperative behavior can be identified by jotting down (+) or (++). Conversely, uncooperative behavior can be noted by (−) or (=). This enables a child’s performance to be discerned at a glance. Similar notation of behavior can be made in computerized patient charts using appropriate software.

Rating scales, such as the Frankl Scale, have two clear shortcomings. First, they do not communicate sufficient clinical information for uncooperative children. If a child is judged to be (−), the scale does not identify the type of negative behavior. Thus, the dentist using this classification system has to qualify as well as categorize the reaction. An example might be: (−) timid. If behavior ranges from negative to positive during a visit, a simple notation could be (− > +). The management technique can also be recorded. TSD shows that behavioral change was accomplished by the T (Tell), S (Show), D (Do) technique (Addelston 1959). Personal abbreviations can be developed for the various situations such as (−) INJ, which reminds the dental team that behavior was negative at the time of injection or VC indicating the use of voice control. Second, a behavioral scale represents a child’s performance during the actual treatment. It has no prognostic value. Nonetheless, it helps clinicians to prepare for the child’s future behavior, based on past performances, and to guide the behavior during treatment instead of simply reacting.

Simple, direct rating scales show a high inter- and intra- observer reliability (Rud and Kisling 1973). Studies have shown substantial correlations between observations of child behaviors during sequential treatment sessions as well as within parts of each treatment appointment (Veerkamp 1995b). Thus, it would be extremely beneficial for dentists to learn and make use of one of the classification systems on child behavior. A few digits are read more easily than a long, detailed report on a child’s behavior.

Before leaving this subject, it is important to note that all clinicians do not perceive behavior in precisely the same way. It follows, therefore, that some dentists feel compelled to develop their own classification consistent with their views of children’s reactions to dentistry. Furthermore, not only do clinicians perceive children’s behavior in different ways, but they also tolerate children’s behavior differently (Alwin et al. 1995).

The interesting concept of the clinician’s “tolerance level” was introduced by Wright (1975) in his original behavior management book. Consider children who present with borderline cooperative-uncooperative reactions to dentistry. What is acceptable to Dr. Jones may be totally unacceptable to Dr. Smith. Certain behavior may be highly irritating to one dentist but only slightly bothersome to another. The dentists have different tolerance levels. They withstand stress differently, and this influences their classifications of children’s behaviors as well their selection of management techniques. Tolerance level is an important but seldom-discussed concept. It helps to explain differences in the numerous descriptive classifications. Moreover, an appreciation of this concept points out the necessity for educators to train dentists in a variety of management techniques.

Descriptions of Behavior

In describing child behavior, the interest or emphasis in the literature has been on behaviors that dentists find difficult to deal with or are inappropriate in some way. However, there are other aspects of behavior that sometimes can be important, and dentists may need to consider these as well. Questionnaires appear in Chapter Six that can be used to investigate children’s environments, how children react to different situations, and how they express fears prior to and during aversive situations. Children’s methods of play and oral habits are forms of behavior. Astute receptionists can observe children playing in the waiting room and often provide important information to the clinician.

When a dentist examines a child patient, one type of behavior—the cooperative behavior—is always assessed because a key to the rendering of treatment is cooperative ability. Most clinicians, consciously or not, characterize children in one of three definable ways (Wright 1975):

Knowing the clinical aspects of these distinctive child behaviors is important to behavior management and treatment planning.

Cooperative Behavior

Most children seen in dental offices cooperate. This is substantiated by dental office experiences, as well as indirect data from behavioral science studies (ten Berge 2001). Cooperative children are reasonably relaxed. They have minimal apprehensions. They may be enthusiastic. Further description of their reactions appears in Frankl’s positive groupings (Table 3-1).

Children judged to be cooperative can be treated by a straightforward, behavior-shaping or tell-show-do approach (see Chapter Six). When guidelines for their behavior have been established, they perform within the provided framework. These children present a “reasonable level” of cooperation, which allows the dentist to function effectively and efficiently. They seldom require pharmacologic adjuncts to help accomplish their treatments.

Lacking Cooperative Ability

In contrast to the cooperative child is the child lacking cooperative ability. This could include very young children (less than three years of age) with whom communication cannot be established. Comprehension cannot be expected. If their treatment needs are urgent, they can pose major behavioral problems. Pharmacologic adjuncts may be required for their treatment. MacDonald (1969) referred to these children as being in the pre-cooperative stage. For these children, time usually solves the behavior problems. As they grow older, they develop into cooperative dental patients and treatment is provided with behavior shaping.

Another group of children who lack cooperative ability are those with specific debilitating or handicapping conditions. The severity of their conditions often prohibits cooperation in the usual manner. Obtaining information on their intellectual development can give the dentist valuable information about the expected level of cooperation. At times, special behavior management techniques, such as body restraints or sedation, are employed to control body movements. While the treatment is accomplished, major positive behavioral changes cannot be expected.

In most western societies, thrust in intellectual impairment services is community-oriented, and as large institutions for the mentally challenged are phased out, more children with special needs are being treated in dental offices today. More and more, these children and adults are living in group and private homes within residential communities. Many dental faculties have recognized this societal change, and programs have been established to prepare undergraduate and post-graduate students to meet the foreseeable demand. Chapter Seven provides a more complete description of the disabled patient.

Potentially Cooperative Behavior

Until recently, the nomenclature applied to a potentially cooperative child was “behavior problem.” The child may be healthy or disabled. However, there is a difference between the potentially cooperative child and the child lacking cooperative ability. The potentially cooperative child has the capability to behave well. It is an important distinction. When characterized as potentially cooperative, the judgment is that the child’s behavior can be modified: the child has the age-related cognitive capacities to learn to deal with dentistry and can become cooperative.

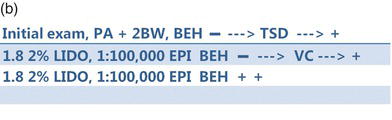

Perhaps one of the most challenging issues for the clinician is to determine what behavior can be expected from the new patient. There are those children who may approach the dental office crying or screaming. Their behavior is apparent. Conversely, there are children who are quiet, shy, or withdrawn. These children can be hard to read. They may or may not be difficult to treat. Behavioral science researchers in dentistry and allied professions have made efforts to predict children’s behaviors before their arrival at a dental clinic. Since the 1990s the Children’s Fear Survey Scale-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) has received considerable attention. Initially presented by Cuthbert and Melamed (1982), the CFSS-DS has been used worldwide. Indeed, it has been translated and tested in various cultures and nations such as Finland, the Netherlands, Bosnia, India, and Japan (ten Berge et al. 1998, Bajric, 2011; Singh, 2010). All venues had similar positive findings when rating fear/anxiety.

Figure 3-3. Items on The Child Fear Survey Schedule—Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS). Krikken et al., 2012, and Milgrom et al., 1995.

The CFSS-DS scale has been used in large patient samples between four and fourteen years of age, it is considered to work well on a group basis, and it has been evaluated as a diagnostic tool on an individual level. In a report comparing properties of different self-report measures, it was concluded that CFSS-DS was preferred, as it has better psychometric properties measuring dental fear more precisely.(Aartman 1998). The psychometric properties were further analyzed and found appropriate for children from four to fourteen years (ten Berge 2001). The test consists of fift/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses