CHAPTER 28. Respiratory tract disease

ACUTE SINUSITIS → Summary p. 448

Clinical features

There is sudden onset of pain from the sinus, often poorly localized, with tenderness of the overlying skin. Teeth with roots in or close to the antrum are painful on pressure. There is also nasal congestion, weakened sense of smell and sometimes referred pain to the ear. Fluid will often discharge into the nose on tilting the head or lying down and movement of the head worsens pain. Involvement of ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses is often perceived by patients as headache.

Management

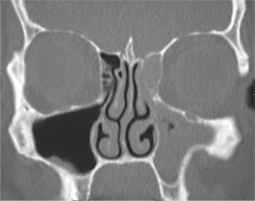

Radiography of the sinuses provides little additional information in acute sinusitis. The diagnosis may usually be made on the history and examination. Computerised tomography is the method of choice if radiographs are required (Fig. 28.1).

|

| Fig. 28.1

Acute sinusitis involving maxillary antrum and ethmoid sinuses, which are completely filled by oedematous sinus lining mucosa and inflammatory exudate.

Courtesy Mr EJ Whaites.

|

Acute sinusitis is self-limiting. No active treatment may be required but nasal decongestants aid drainage, speed recovery and provide symptomatic relief. Many patients manage well with non-prescription steam inhalations containing menthol or eucalyptus oils. More severe cases benefit from ephedrine or oxymetazoline nose drops, but these should not be continued for more than 7 days.

Bacterial infection is uncommon and antibiotic treatment is not indicated, at least initially. Persistence or worsening of symptoms after 10 days or presence of pus suggest bacterial infection and development of chronic sinusitis. The usual organisms are aerobes such as Strep. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and beta-haemolytic streptococci. Staph. aureus is a more frequent isolate from the sphenoid sinus. These pathogens frequently show antimicrobial resistance and either high-dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin with clavulanic acid are appropriate empirical first-line drugs. If these fail, a pus sample for sensitivity testing must be obtained by puncture of the sinus.

Dental causes need to be excluded, but are present in only 5% of cases and are much more likely to be identified in chronic sinusitis (see below).

Though most cases resolve, sinusitis may become recurrent or chronic.

CHRONIC SINUSITIS → Summary p. 448

Chronic sinusitis may develop with or without a preceding acute sinusitis.

The clinical features are those of the acute disease but milder and without the generalised symptoms of upper respiratory tract viral infection. When pain is poorly localised, radiographic examination of the sinuses may reveal mucosal thickening or a fluid level. Computerised tomography is the examination of choice (Fig. 28.2), but the maxillary antrum is well visualised on panoramic tomography or occiptomental view.

|

| Fig. 28.2

Chronic sinusitis with an antral polyp, a localised area of mucosal oedema and thickening. Mucosal thickening or polyps on the floor of the antrum indicate a need to exclude dental and periodontal causes.

Courtesy Dr S Connor. See also Fig. 28.3.

|

Management

Dental causes are relatively frequent. The roots of the maxillary molar teeth lie close to or within the antrum. In some patients, the root apex perforates the cortex so that only mucous membrane covers it. The commonest dental causes of sinus inflammation are therefore periapical periodontitis from a non-vital molar, extraction, root treatment or severe periodontal disease. Non-dental causes include fractures. These are best identified by vitality testing, clinical examination and dental radiography.

When no dental cause is present, the bacteria are initially those found in acute sinusitis, but the flora gradually shift to an anaerobic population after 3 months. When dental infection is a factor, additional anaerobic oral bacteria such as Prevotella spp. and Fusobacterium spp. are found. Antibiotic treatment is only effective in conjunction with removal of the cause. Appropriate regimens are amoxicillin with clavulanic acid or a penicillin with metronidazole or as guided by culture and sensitivity.

If dental and other local causes are confidently excluded or treated and treatment fails, the patient should be referred to investigate the possibility of nasal predisposing causes such as polyps, allergic or fungal sinusitis.

Fungal sinusitis

Sinusitis results from inhalation of air-borne fungal spores. These would normally be cleared by mucociliary transport but become trapped if the transport is compromised by inflammation or if the spores germinate or trigger an allergic reaction. The causative fungi grow in soil and their spores are widespread in the enviroment.

The commonest type is a ‘fungus ball’ or mycetoma, a tangled mass of fungal hyphae bound together with mucous and inflammatory exudate. The ball may grow to fill the sinus and is commonly Aspergillus spp. Radiographic diagnosis is aided by the frequent presence of spotty mineralisation in the fungus ball.

Mycetoma formation has been associated with particles of zinc-containing root filling material. These presumably enter the sinus after root treatment and may sometimes be seen on radiographs. Inflammation from apical periodontitis would favour retention of spores and zinc encourages fungal growth.

In those mounting a florid allergic reaction to the fungus, the sinuses fill with thick secretions containing numerous eosinophils but fewer fungal hyphae. Some studies have suggested that almost all cases of chronic sinusitis refractory to treatment are caused by these fungi, usually black pigmented species such as Bipolaris spp.

Mycetomas and allergic fungal sinusitis are treated by surgical removal of the fungus followed by topical or systemic antifungal treatment.

In the immunocompromised, the fungi may invade the sinus wall, cause rapid extensive destruction and often a fatal outcome. Such cases are caused by more virulent environmental fungi such as Mucor spp. and require aggressive surgical and antifungal treatment.

SURGICAL DAMAGE TO THE MAXILLARY ANTRUM

The floor of the antrum may be damaged during dental extractions which cause an oroantral communication. If the antrum is opened during an extraction, a displaced root or bacteria from the mouth can introduce infection. There is also damage to the ciliated lining and loss of normal mucociliary transport which carries foreign material out of the cavity. If sinusitis becomes established and the fistula has not been closed, the walls of the passage may become epithelialised and the opening becomes a permanent fistula.

Displacement of a root or tooth into the maxillary antrum

A whole tooth can be driven into the antrum if the tooth is conical and considerable upward force has been used. More frequently, a root is driven into the antrum when an attempt is made to dig it out via the socket, particularly when a thin antral floor extends down into the alveolar ridge.

Clinical features

Displacement of a tooth or root into the antrum can give rise to signs (Box 28.1), partly depending on the size of the opening.

Box 28.1

Signs suggesting a tooth or root displaced into the antrum

• The root or tooth suddenly disappears during the extraction

• Blowing the nose may force air into the mouth or cause frothing of blood from the socket

• The patient may notice air entering the mouth during swallowing, or fluid from the mouth escapes into the nose

• Bleeding from the nose on the affected side, occasionally

• Later, a salty taste or unpleasant discharge

• Facial pain if acute sinusitis develops

• Rarely, antral lining may prolapse into the mouth

Management

The position of the root or tooth should be confirmed. Sometimes it is still within the alveolar process or outside the antrum and between its lining and bony floor.

A root displaced into the antrum usually causes sinusitis, but it may cause no more than mucosal thickening. Severe sinusitis is less common. The root should be removed from the antrum and any oroantral opening closed. Several measures are important (Box 28.2).

Box 28.2

Principles of management of a root displaced into the antrum

• Explain to the patient how the accident has happened and give the necessary reassurance

• Do not to try to retrieve the lost root immediately by digging through the socket opening and damaging the antral floor and lining further

• If a root or tooth has been displaced into the antrum, it should be removed by elective surgery (see below)

• If the tip of a root causes a minimal antral reaction or lies between the bony floor and the mucosal lining, removal may not be essential but there is a risk of infection later

After any acute sinusitis has been treated, the surgical approach depends on the position of the root and whether there is a wide oroantral opening. The usual method is to reflect a mucoperiosteal flap in the labiobuccal sulcus, open the antrum in the canine fossa (Caldwell–Luc approach) and find the root by endoscopy. The tooth or fragment may then be removable on a sucker nozzle small enough to prevent it from disappearing into the suction apparatus and being lost before confirmation of its removal.

Oroantral fistula

Rarely, the antrum may be accidentally opened during extractions if the antral floor is damaged. If the communication is not obvious, its presence may be verified by telling the patient to blow gently while blocking the nose by pinching the nostrils together. Air (detectable with a tuft of cotton wool held in tweezers), blood, pus, or mucus will then be expelled from the opening into the mouth. Occasionally, an opening may be blocked by prolapsed lining or antral polyp which is purplish red (Fig. 28.3) and, if the opening is large enough, it may sometimes be pushed gently back into the antrum, thus confirming its origin. Alternatively, a silver probe can be gently insinuated beside the mass into the antral cavity to detect the opening.

|

| Fig. 28.3

Antral polyp. A polyp of inflamed antral mucosa has prolapsed through an oroantral fistula left untreated after the extraction of an upper first permanent molar.

|

Epithelialisation of the communication forms a fistula, which is thereby prevented from healing spontaneously. Usually, a large oroantral fistula gives adequate drainage, but a pinhole fistula blocks drainage and is often associated with recurrent attacks of sinusitis. If the patient is not seen until late after the accident, there is typically chronic antral infection, persistent discharge and proliferation of granulation tissue. The inflamed antral lining is usually much thickened and polyps may fill part of the cavity.

Principles of management are summarised in Box 28.3.

Box 28.3

Principles of management of an oroantral communication

The communication (non-epithelialised)

• Reflect a mucoperiosteal flap and suture it to give an air-tight seal over the opening

The established fistula (epithelialised communication) with infection

• Control chronic sinusitis by removal of any polyps, usually via a Caldwell–Luc approach, or through the oral opening if the fistula is sufficiently large

• Excise the entire epithelialised fistula

• Close the opening by reflecting a mucoperiosteal flap over it

Postoperatively

• Give penicillin for 5 days and a 10-day course of decongestant nose drops and inhalations

• Warn the patient against blowing the nose

Aspiration of a tooth, root or instrument

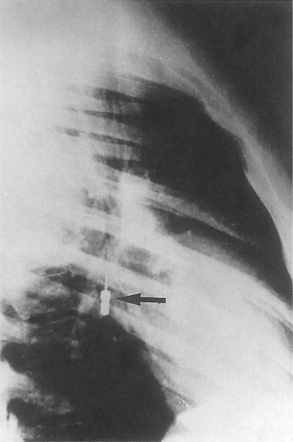

A tooth or root can rarely slip from extraction forceps but is more frequently swallowed than inhaled. The patient should be reassured but should be sent for a chest radiograph and, if necessary, bronchoscopy. Small instruments such as reamers can also occasionally be inhaled (Fig. 28.4).

|

| Fig. 28.4

Radiograph of the chest used to localise an inhaled reamer.

|

If left, a tooth in a bronchus can cause collapse of the related lobe and a lung abscess.

COMMON VIRAL UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS (‘COLDS’)

Colds often precede sinusitis. They are a contraindication to general anaesthesia. Transmission to the dentist is also a hazard.

TUBERCULOSIS

Dentists and dental personnel in the UK should all have received a BCG vaccination and be immune to tuberculosis, though occasional individuals respond poorly. A non-immune dentist is at significant risk from acquiring tuberculosis from such patients, in some of whom the infection is unsuspected or dismissed as ‘smokers’ cough’. This can be particularly dangerous if the mycobacteria are multiply drug-resistant.

Rigorous infection control must therefore be maintained, particularly now that the incidence of tuberculosis is rising.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses