chapter 27 Intravenous Sedation: Complications

The complications associated with IV drug administration are divided into four groups: (1) those associated with venipuncture, (2) localized complications related to drug administration, (3) general drug-related problems, and (4) drug-specific complications. These are outlined in Box 27-1.

Box 27-1

Complications Associated With IV Drug Administration

VENIPUNCTURE COMPLICATIONS

Nonrunning Intravenous Infusion

IV Infusion Bag Too Close to the Heart Level

Gravity forces the IV infusate from the bag down into the patient. The greater the difference in height between the bag and the patient’s heart is, the more rapid the flow of solution can be. A simple experiment demonstrates this: The IV bag is held high above the patient’s heart level, and the rate of flow is checked. With the rate-adjusting knob opened fully, the drip should be rapid. As the bag is gradually lowered toward the level of the patient’s heart, the rate of flow of the drip decreases until, when held at the patient’s heart level, the flow ceases entirely. When the bag is lowered below the level of the patient’s heart, blood returns into the tubing (Figure 27-1).

Bevel of Needle Against Wall of Vein

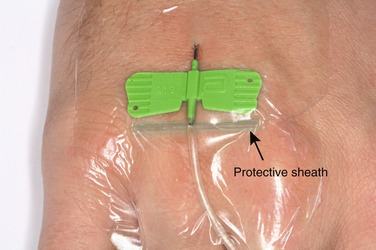

To determine whether this is the cause of a slow or nonrunning drip, the needle is carefully untaped and the wings of the butterfly needle gently lifted. This lowers the bevel of the needle off the wall of the vein. If the drip rate increases, the protective cap from the scalp vein needle (Figure 27-2) or a 2 × 2-inch gauze square is carefully placed under the wings of the needle and the needle retaped.

This is not likely to occur when an indwelling catheter is used for venipuncture because there is no bevel on the catheter. However, when a catheter is positioned in either the dorsum of the hand or antecubital fossa, it is possible for the tip of the catheter to lie in a bend in the vein, creating a slow flow of IV solution (Figure 27-3). Determine this by straightening the patient’s wrist or elbow and looking for an increase in the rate of flow of the IV drip. This may be minimized by preventing the patient from bending the joint through the use of an elbow immobilizer or wrist board.

Tourniquet Left on Arm

An embarrassing but not uncommon cause of a nonrunning IV drip following successful venipuncture may simply be that the tourniquet has been left on the patient because it has become hidden by a sleeve of a garment that has inched down. Following the return of blood into the IV tubing, the dentist or assistant opens up the control knob to start the IV drip. It is noted that the drip is not flowing and that blood does not leave the IV tubing as normally occurs. It is usually noted that more blood appears to be entering the IV tubing (as it is forced from the vein into the tubing) (Figure 27-4). Once excessive blood is noticed in the tubing, simple removal of the tourniquet will alleviate this embarrassing situation.

Hematoma

Prevention

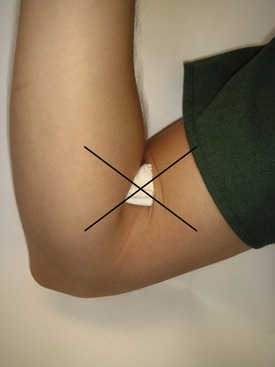

It is not always possible to prevent hematoma during venipuncture, although careful adherence to recommended technique minimizes its likelihood. Hematoma developing after the procedure may be prevented by application of firm pressure for a minimum of 5 to 6 minutes. The commonly used technique of placing gauze over the venipuncture site in the antecubital fossa and having the patient flex his or her arm (illustrated in Figure 27-5) does not always provide pressure adequate to prevent hematoma.

Infiltration

Prevention

Infiltration can be prevented by careful venipuncture technique and by not starting the IV drip or injecting drugs until it has been confirmed that the needle tip or catheter still lies within the lumen of the vein. Checking for this is quite easy. The rubber flash bulb on the IV tubing may be squeezed with blood returning into the tubing when the pressure is released, or the IV bag may be held below the level of the patient’s heart (Figure 27-6).

Air Embolism

In the highly likely event that one or more small bubbles of air enter into the venous circulation, they will be absorbed by the blood quite rapidly with no clinical sequelae. It is not always possible for all air bubbles to be removed from the IV tubing or syringes, and it is quite probable that small bubbles may enter into the venous circulation of the patient. The patient, noticing the air bubble moving slowly down the IV tubing toward his or her arm, may become quite anxious, believing (from television or movies) that as little as one bubble of air is lethal. Fortunately, this is not so. A rule of thumb in a hospital environment is that a patient can tolerate up to 1 ml/kg of body weight of air in the peripheral venous circulation without adverse effect.1

The typical IV administration set can hold approximately 13 ml of air.2 Because 10 drops of solution (or air) equals 1 ml (adult infusion set), the chances of introducing large volumes of air into the patient’s circulation are extraordinarily low. A 50-kg (110-lb) patient can tolerate 50 ml of air. This is equivalent to 500 to 750 drops of air from an adult IV administration set (10 or 15 drops/ml).

Overhydration

A rule of thumb for replacement of fluid in a patient is that the initial dose of IV solution administered is equal to 1.5 times the number of hours a patient has gone without food times the patient’s weight in kilograms.3 This is the volume of fluid in milliliters required to replace the fluid deficit created by the patient’s taking nothing by mouth (NPO) before the procedure. If a patient has been NPO for 6 hours before coming to the office, the initial volume of IV solution administered is nine times the patient’s body weight in kilograms. The maintenance dose of IV solution is 3 ml/kg. The problem of underhydration is not significant in the usual outpatient environment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses