Chapter 24

Scalp reconstruction

Introduction

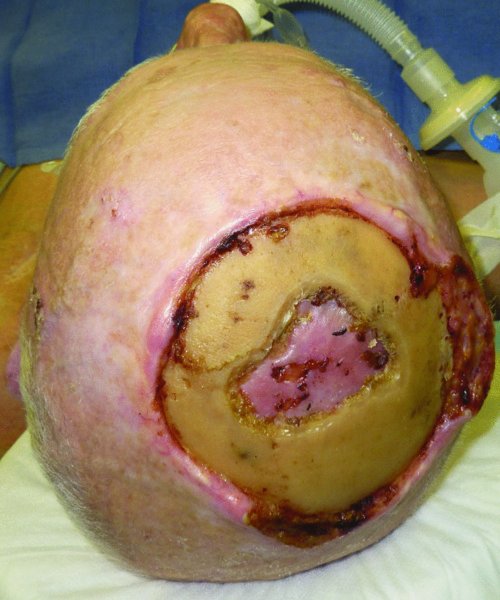

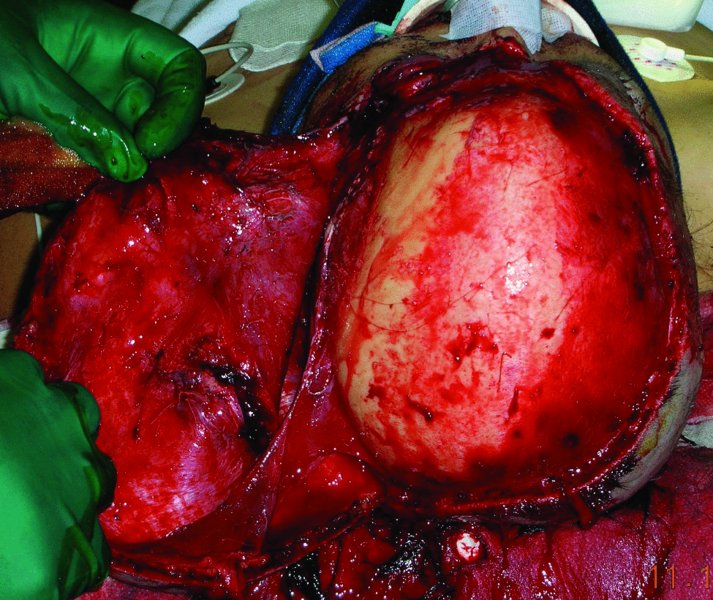

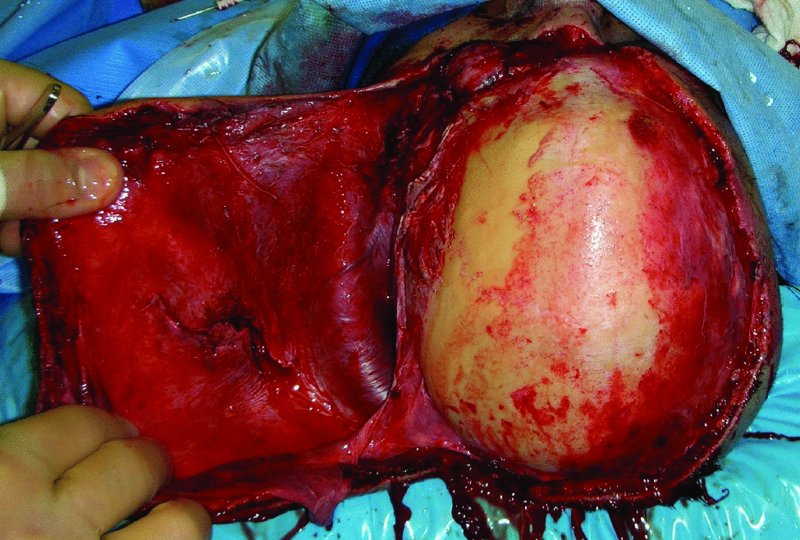

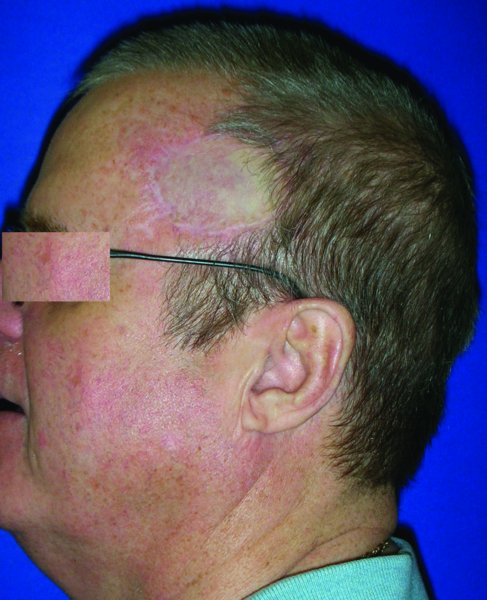

The reconstruction of scalp defects can be very challenging. The location and size of the defect can influence the degree of complexity for the surgeon. Defects of the scalp are most often encountered due to the presence of malignant lesions (Figures 24.1 and 24.2), after radiation (Figure 24.3), and occasionally due to trauma (Figure 24.4). The inherent challenges in the reconstruction of scalp defects is the status of the remaining scalp tissue as it relates to the existing blood supply and previous exposure to radiation therapy.

Figure 24.1 View of a large neglected scalp malignancy.

Figure 24.2 Appearance of a very large scalp malignancy with destruction of the calvarium.

Figure 24.3 View of a large exposed calvarium after previous radiation therapy to the scalp. Note recurrent disease on the right lateral aspect.

Figure 24.4 View of a large avulsive injury of the forehead and scalp with exposed cranium.

Many authors have described their approaches to scalp reconstruction. A name commonly associated with scalp reconstruction is Orticochea. Dr. Mario Orticochea made significant contributions to the reconstruction of scalp defects with his description of the four-flap 1 reconstruction and later the three-flap technique reconstruction, which improved the vascularity of the elevated flaps and the success of the reconstruction.2 His contributions have come to be referenced to as the banana peel flaps. Since then others have incorporated newer techniques such as the use of tissue expanders to aid and at times improve the overall reconstruction of complex scalp defects.3,4 Equally, the addition of microvascular techniques has increased our ability to reconstruct scalp defects that would previously have been deemed inoperable.5

The reconstructive surgeon involved in scalp reconstruction has to pay particularly close attention to the location of the hairline and the use of flaps so the normal hairline is not disrupted. Successful scalp reconstruction often requires intraoperative use of the intrinsic viscoelastic properties of skin, specifically, stress relation and creep.8

Anatomy

The skin of the forehead, scalp, and nape of neck constitute a single anatomic subunit.6

The layers of the scalp can be remembered according to the mnemonic SCALP: S skin, C subcutaneous tissue, A aponeurotic layer, L loose areolar tissue, and P pericranium.7 The galea aponeurosis, the strength layer of the scalp, is contiguous with the paired frontalis muscles anteriorly, the paired occipitalis muscles posteriorly, and the temporoparietal fascia laterally.8 The ability to move the scalp is gained by the loose areolar plane.

The scalp has a very rich blood supply, which it receives from both the internal as well as the external carotid systems. The blood supply to the anterior scalp is from the paired supraorbital vessels and the supratrochlear vessels. The lateral supply comes from the superficial temporal vessels. The posterior blood supply to the scalp comes from the occipital vessels which supply the territory above the nuchal line and from perforators from the trapezius and splenius capitus.

The scalp can be divided into tight and loose regions based on the underlying tissue. In areas where no muscle or fascia is present, the scalp is tight (centrally), whereas in areas where these components are present, the scalp is loose (peripherally).6

Defect assessment

Site and size oriented approach to reconstruction

The approach to the reconstruction of scalp defects can be broken down into its basic components as falling into one of the following categories: primary closure, healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, local or regional flaps, and lastly, microvascular reconstruction. The next sections will develop each category and provide case examples to substantiate each option. When discussing each option, the pros and cons of the particular reconstructive technique will be highlighted.

Primary wound closure

Scalp defects amenable to primary closure may result from the resection of small tumors or more commonly from trauma. Traumatic scalp defects are often misdiagnosed during the primary assessment as missing significant amount of tissues. The reason for this common misdiagnosis is due to the resultant contraction of the scalp (Figure 24.5). Upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that the tissues are not missing and that there is adequate tissue for primary repair of the scalp.

Figure 24.5 Appearance of a large laceration of the scalp extending from the frontal region to the occipital region.

Defects originating from ablative procedures that would be amenable for primary closure are typically very small. The defects that would fall into this category are usually not referred to the reconstructive surgeon. They are often repaired by the ablative surgeon.

Case #1

A middle-aged Caucasian female was involved in a motor vehicle accident and suffered significant injuries. One of her injuries was a near scalp amputation (Figures 24.6 and 24.7). The patient was taken to the operating room where there scalp was thoroughly irrigated and all debris were removed (Figure 24.8). The scalp was then evaluated for vascularity and overall integrity. The scalp was then repaired with primary closure over suction drains (Figure 24.9). The appearance of the patient several months after the injury shows an acceptable repair of the near total scalp avulsion with normal hair growth (Figure 24.10).

Figure 24.6 View of a scalp avulsion pedicled on a small portion of the left posterior scalp.

Figure 24.7 Exposure of a large scalp laceration pedicled on the left.

Figure 24.8 Appearance after washout and debridment in the operating room.

Figure 24.9 Repaired scalp.

Figure 24.10 Postoperative appearance of the repaired scalp.

Skin grafts

The use of skin grafts to reconstruct scalp defects is generally relegated to patients with significant medical comorbidities that would preclude them from more complex reconstructions, or to those patients in whom a staged reconstruction is contemplated. When staging the reconstruction with a skin graft, it is usually anticipated that the patient will have a tissue expander put in place and the expanded tissue used later to repair the original defect with hair-bearing scalp tissue (Figures 24.11 and 24.12).

Figure 24.11 View of a tissue expander placed on the left scalp prior to takedown and scalp reconstruction.

Figure 24.12 Repair of the scalp after advancement and rotation of the expanded scalp.

When contemplating the use of a skin graft for scalp reconstruction, the ablative surgeon should preserve the pericranium whenever possible. The successful take of the skin graft is significantly increased when the recipient tissue bed is composed of a vascularized soft tissue.

The use of skin grafts should be avoided in patients with a history of radiation therapy to the scalp or in those patients where the skull is barren. In these situations the likelihood of graft take is significantly less than in those cases where these issues are not present. If circumstances mandate an attempt at skin grafting the denuded skull, small drill holes should be made to bring bleeding points to the bed in the hope of improving the take of the graft. The skin graft should be a split graft with fenestrations.

Case #2

A 49-year-old Caucasian male presented with a biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the anterior lateral scalp region (Figure 24.13). The area for resection was marked and the lesion was removed with frozen section margin assessment (Figures 24.14 and 24.15). A split thickness skin graft was then harvested and grafted to the defect and a bolster dressing was placed (Figure 24.16). The patient was pleased with his final reconstructive appearance (Figure 24.17).

Figure 24.13 Appearance of a left scalp malignancy which extends slightly to the forehead.

Figure 24.14 Markings for the excision of the lesion.

Figure 24.15 Appearance of the defect after resection of the tumor.

Figure 24.16 Skin graft reconstruction of the scalp defect.

Figure 24.17 Late appearance of the reconstruction of the defect with a skin graft.

Case #3

An 87-year-old Caucasian male with multiple comorbidities was referred for the management of a biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the scalp vertex (Figure 24.18). Due to the patient’s overall poor health status, a decision was made for a resection and immediate reconstruction with a split thickness skin graft. This decision was felt to be the quickest way to get the patient reconstructed and off the operating table in the hope of minimizing operative and perioperative complications. The lesion was resected with a wide margin (Figures 24.19 and 24.20). The pericranium was left intact to increase the take of the graft. A large skin graft was harvested and grafted to the defect site (Figure 24.21). A large bolster dressing was made and wrapped with a petroleum-based dressing and secured in place with circumferential staples (Figures 24.22 and 24.23). The final appearance of the reconstructed scalp was acceptable with a complete take of the skin graft (Figure 24.24).

Figure 24.18 Markings for a large scalp resection of a squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 24.19 Excision of the tumor.

Figure 24.20 View of the defect and scalp bed prior to repair with a skin graft.

Figure 24.21 Skin graft repair of the scalp defect.

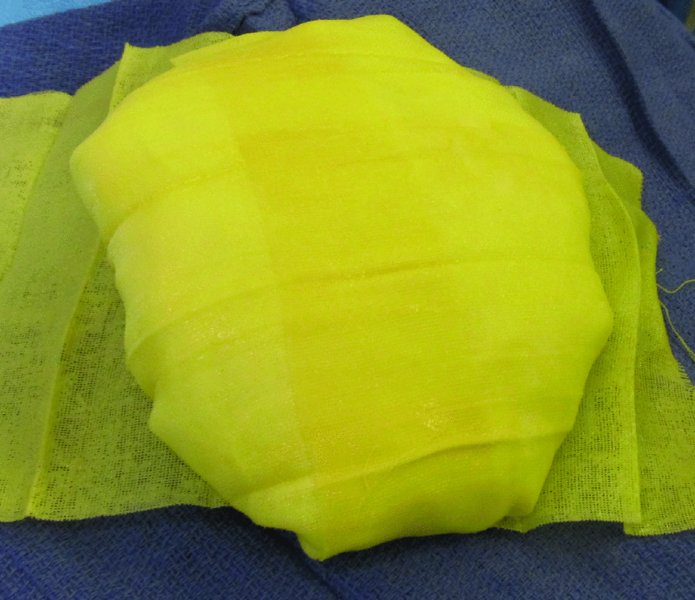

Figure 24.22 Making of a bolster dressing to be used in the scalp.

Figure 24.23 Placement of the bolster dressing to secure the skin graft in the scalp.

Figure 24.24 Postoperative appearance of the reconstructed scalp with the skin graft.

Figure 24.25 Markings for a wide local excision of a scalp malignancy with possible options of rhomboid flaps.

Local flaps

A comprehensive understanding of the vasculature of the scalp and the inherent properties of scalp tissue allows for numerous local flap options in the reconstruction of various scalp defects. The use of transposition flaps, rotational flaps, and various other combinations can be routinely used to repair moderate to large scalp defects.

The options for the reconstruction of moderate to large scalp defects include the use of multiple rhomboid flaps as previously described in Chapter 4, use of the hatchet flap as described by Emmett in 1977,9 or rotational flaps such as the pin wheel or Ying Yang flap.

Case #4: Multiple rhomboid flap

The use of the rhomboid flap to reconstruct various defects including the scalp was discussed in Chapter 4. This case illu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses