The Edentulous Mandible

Treatment Plans for Implant Overdentures

Carl E. Misch

The complete edentulous population comprises more than 10% of the adult population and is directly related to the age of the patient. By the age of 70 years old, almost 45% of the population has no teeth in either arch. The vast majority of these patients are treated with complete dentures. Yet the dental profession and the public are more aware of the problems associated with a complete mandibular denture than any other dental prosthesis.

The placement of implants enhances the support, retention, and stability of an overdenture. As a result, edentulous patients are very willing to accept a treatment plan for a mandibular implant overdenture (IOD). There is greater flexibility in implant position or prosthesis fabrication with a mandibular IOD; as a result, it is also an ideal treatment modality to begin an early learning curve in implant surgery and prosthetics. Therefore, one of the most beneficial treatments rendered to patients is also one of the best introductions for a dentist into the discipline of implant dentistry.

An increased awareness from the profession and patients has now rendered the mandibular IOD the treatment of choice in the edentulous patient regardless of most clinical situations, bone densities, and patients’ desires to restore an ever-growing number of patients.1–38 As a consequence, mandibular overdentures have become the minimum standard of care for most completely edentulous mandibles.

Advantages of Mandibular Implant Overdentures

The patient gains several advantages with an implant-supported overdenture prosthesis.7,8,11 (Box 23-1). The complete mandibular denture often moves during mandibular jaw movements during function and speech. A mandibular denture may move 10 mm during function. Under these conditions, specific occlusal contacts and the control of masticatory forces are nearly impossible. An IOD provides improved retention and stability of the prosthesis, and the patient is able consistently to reproduce a determined centric occlusion.39

Bone loss after complete edentulism, especially in the mandible, has been observed for years in the literature.39–41 Soft tissue abrasions and accelerated bone loss are more symptomatic of horizontal movement of the prosthesis under lateral forces. An implant-supported overdenture may limit lateral movements and direct more longitudinal forces. The anterior implants stimulate the bone and maintain the anterior bone volume.40–44 The attachment of the mentalis muscle and others are maintained as a result and therefore improve facial esthetics.

Higher bite forces have been documented for mandibular overdentures on implants. The maximum occlusal force of a patient with dentures may improve 300% with an implant-supported prosthesis.44,45 A study of chewing efficiency compared wearers of complete dentures with wearers of implant-supported overdentures. The complete denture group needed 1.5 to 3.6 times the number of chewing strokes compared with the overdenture group.38 The chewing efficiency with an IOD is improved by 20% compared with a traditional complete denture.6,7,46,47

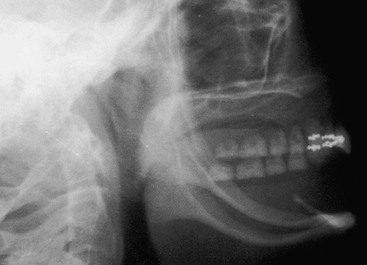

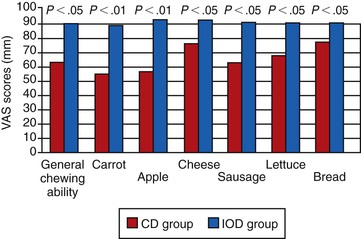

Mericke-Stern48 and Mericke-Stern et al.49 also compared mastication between root overdentures and IODs. Whereas the former was more discriminative, the latter developed slightly harder chewing strokes and tended to masticate more vertically. Jemt et al.50 showed a decrease in occlusal force when the bar connecting implants was removed, which they attributed to the loss of support, stability, and retention. As a result of improved mastication, patients with IODs can chew significantly better than with their complete dentures6 (Figure 23-1).

The contraction of the mentalis, buccinator, or mylohyoid muscles may lift a traditional denture off the soft tissue. As a consequence, the teeth may touch during speech and elicit clicking noises. The retentive IOD remains in place during mandibular movement. The tongue and perioral musculature may resume a more normal position because they are not required to limit mandibular denture movement.

The IOD may reduce the amount of soft tissue coverage and extension of the prosthesis. This is especially important for new denture wearers, patients with tori or exostoses, and patients with low gagging thresholds. Also, the existence of a labial flange in a conventional denture may result in exaggerated facial contours for a patient with recent extractions. Implant-supported prostheses do not require labial extensions or extended soft tissue coverage.

Soft and hard tissue defects from tumor excision or trauma do not permit the successful rehabilitation of patients with traditional denture support. Hemimandibulectomy patients and other maxillofacial patients also may be restored more favorably with an IOD compared with traditional procedures.51

An IOD also provides some practical advantages over an implant-supported complete fixed partial denture (Box 23-2). Fewer implants may be required when a RP-5 restoration is fabricated because soft tissue areas may provide additional support. The overdenture may provide stress relief between the superstructure and prosthesis, and the soft tissue may share a portion of the occlusal load. Regions of inadequate bone for implant placement therefore may be eliminated from the treatment plan rather than necessitating bone grafts or placing implants with poorer prognosis. As a result of less bone grafting and number of implants, the cost to treat the patients is dramatically reduced.

When cost is a factor, a two-implant-retained IOD may improve the patient’s condition at a lower overall treatment cost than a fixed implant–supported prosthesis.52 A survey by Carlsson et al. in 10 countries indicated a wide range of treatment options.53 The proportion of IOD selection versus fixed implant dentures was highest in the Netherlands (93%) and lowest in Sweden and Greece (12%). Cost was cited as the top determining factor in the choice.

The esthetics for many edentulous patients with moderate to advanced bone loss are improved with an overdenture compared with a fixed restoration. Soft tissue support for facial appearance often is required for an implant patient because of advanced bone loss, especially in the maxilla. Interdental papilla and tooth size are easier to reproduce or control with an overdenture. Denture teeth easily reproduce contours and esthetics compared with time-consuming and technician-sensitive porcelain metal fixed restorations. The labial flange may be designed for optimal appearance, not daily hygiene. In addition, abutments do not require a specific mesiodistal placement for an esthetic result because the prosthesis completely covers the implant abutments.

Hygiene conditions and home and professional care are improved with an overdenture compared with a fixed prosthesis. Periimplant probing is easier around a bar than a fixed prosthesis because the crown contour often prevents straight-line access along the abutment to the crest of the bone. The overdenture may be extended over the abutments to prevent food entrapment during function in the maxilla.

An overdenture may be removed at bedtime to reduce the noxious effect of nocturnal parafunction, which increases stresses on the implant support system. In addition, a fixed prosthesis is not desired as often for a long-term denture wearer. Long-term denture patients do not appear to have a psychologic problem associated with a removable restoration versus a fixed prosthesis.54–62

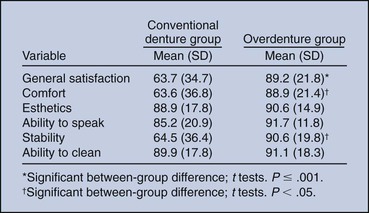

In a randomized clinical report, Awad et al.6 compared satisfaction and function in complete denture patients versus patients with two implant-supported mandibular overdentures. There were significantly higher satisfaction, comfort, and stability in the IOD group (Figure 23-2). A similar study in a senior population yielded similar results.7 Thomason et al., in the United Kingdom, also reported a 36% higher satisfaction for implant IOD patients than complete denture wearers in the criteria of comfort, stability, and chewing.8

The overdenture prosthesis is usually easier to repair than a fixed restoration. Reduced laboratory fees and fewer implants allow the restoration of patients at reduced costs compared with a fixed prosthesis.

In conclusion, the primary indications for a mandibular IOD relate to problems found with lower dentures such as lack of retention or stability, decrease in function, difficulties in speech, tissue sensitivity, and soft tissue abrasions. If an edentulous patient is willing to remain with a removable prosthesis, an overdenture is often the treatment of choice. In addition, if cost is a problem for a patient who desires a fixed restoration, the overdenture may serve as a transitional device until additional implants may be inserted and restored.

Philosophy for Implants in the Edentulous Mandible

From a bone volume conservation standpoint in the jaws, complete edentulous patients should be treated with enough implants to completely support a prosthesis whether the patient is partially or completely edentulous. The continued bone loss after tooth loss and associated compromises in esthetics, function, and health make all edentulous patients implant candidates. These issues are addressed in Chapter 1. The average denture patient does not see a dentist regularly. In fact, more than 10 years usually separates dental appointments of edentulous patients. As a consequence, patients are unaware of the insidious loss of bone in the edentulous jaw.

During the long hiatus between dental visits after dentures are used to replace the dentition, the amount of resorption from initial denture delivery to the next professional interaction already has caused the destruction of the original alveolar process. The bone loss that occurs during the first year after tooth loss is 10 times greater than in following years. In the case of multiple extractions, this often means a 4-mm vertical bone loss within the first 6 months. This bone loss continues over the next 25 years, with the mandible experiencing a fourfold greater vertical bone loss than the maxilla 35(Figure 23-3). As the bony ridge resorbs in height, the muscle attachments become level with the edentulous ridge.39,40 The more often a patient wears a denture, the greater the bone loss, yet 80% of denture patients wear their dentures day and night. To the contrary, the anterior bone under an overdenture may resorb as little as 0.6 mm vertically over 5 years, and long-term resorption may remain at less than 0.05 mm per year.4,35,43

Therefore, the profession should treat bone loss after tooth extraction in a similar fashion as bone loss from periodontal disease. Rather than waiting until the bone is resorbed or the patient complains of problems with the prostheses, the dental professional should educate the patient about the bone loss process after tooth loss. In addition, the patient should be made aware the bone loss process can be arrested by a dental implant. Therefore, most completely edentulous patients should be informed of the necessity of dental implants to maintain existing bone volume and improve prosthesis function, masticatory muscle activity, esthetics, and psychologic health.

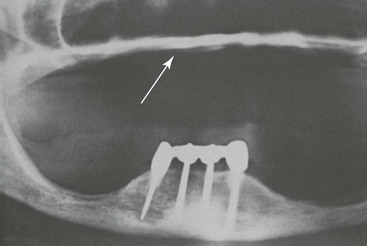

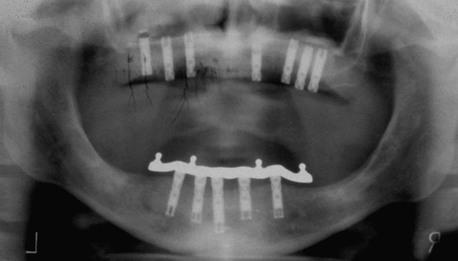

The majority of mandibular overdentures used by the profession are supported by two implants anterior to the foraminae and soft tissue support in the posterior regions (Figure 23-4). Yet posterior bone loss occurs four times faster than anterior bone loss. In a completely edentulous patient, the eventual paresthesia and mandibular body fractures are primarily from posterior bone loss (Figure 23-5). The anterior implants allow improved anterior bone maintenance, and the prosthesis benefits from improved function, retention, and stability. However, the lack of posterior support in two- and three-implant overdentures allows continued posterior bone loss. A primary concern for RP-5 overdentures (soft tissue support in the posterior regions) compared with RP-4 or fixed restorations (restorations completely supported, retained, and stabilized) is the continued bone loss in the posterior regions. The posterior bone resorbs faster than the anterior bone, and implant prostheses with posterior soft tissue support may accelerate posterior bone resorption two to three times faster than in a complete denture wearer.41–43 Therefore, the short-term benefit of decreased cost for RP-5 overdentures may be offset by the accelerated bone loss that is a primary consideration, especially in younger edentulous patients.

Patients wearing fixed implant–supported prostheses show little to no bone loss and usual occurrences of bone apposition.44,63 For example, studies by Wright et al.31 and Reddy et al.40 found prostheses completely supported by implants in the edentulous mandible actually may increase the posterior bone volume (even though posterior implants are not inserted) (Figure 23-6). Therefore, the next progression in the implant philosophy is to convert all mandibular implant and soft tissue–supported restorations to a completely implant-supported prosthesis. As a result, complete implant–supported restorations should be the restoration of choice.

As a consequence of continued posterior bone loss with a two- or three-implant overdenture, the recommendation is to consider a RP-5 prosthesis as an interim device designed to enhance the retention of the prosthesis. These restorations should not be considered an end result for all patients. Instead, a regular evaluation of patients’ performance paired with patient education should enable the transformation to a RP-4 or FP-3 (fixed prosthesis) restoration. In addition, reports indicate that RP-5 mandibular IODs may cause a combination-like syndrome, with increased looseness, subjective loss of fit, and midline fracture of the upper denture.64–68 Although not yet established as a cause-and-effect situation, the condition may be reduced with a proper occlusal scheme.66

Financial considerations have been identified as the reason for the selection of a limited treatment, which may consist of two or three implants to support the overdenture.14,25,34 These RP-5 restorations may be used as transitional devices until the patient can afford to upgrade the restoration. When a partially edentulous patient cannot afford to replace four missing first molars, the dentist often will replace one molar at a time over many years. Likewise, the dental implant team can insert one or two additional implants every few years until finally a complete implant–supported prosthesis is delivered.

The ultimate goal of bone maintenance with a complete implant–supported prosthesis may be designed in the beginning of treatment even though it may take many years to complete. The advantage of developing a treatment plan for long-term health, rather than short-term gain, is beneficial to the patient. As such, if finances are not an issue, the dentist should design a prosthesis that is completely supported, retained, and stabilized by implants. If cost is a factor, a transitional implant-retained restoration with fewer implants greatly improves the performance of a mandibular denture. Then the dentist may establish a strategy for the next one or two steps to obtain the final complete implant–supported restoration.

Disadvantages of Implant Overdentures

The primary disadvantage of a mandibular overdenture is related to the patient’s desire, primarily when he or she does not want to be able to remove the prosthesis. A fixed prosthesis often is perceived as an actual body part of the patient, and if a patient’s primary request is not to remove the prosthesis, an implant-supported overdenture would not satisfy the psychological need of the patient.

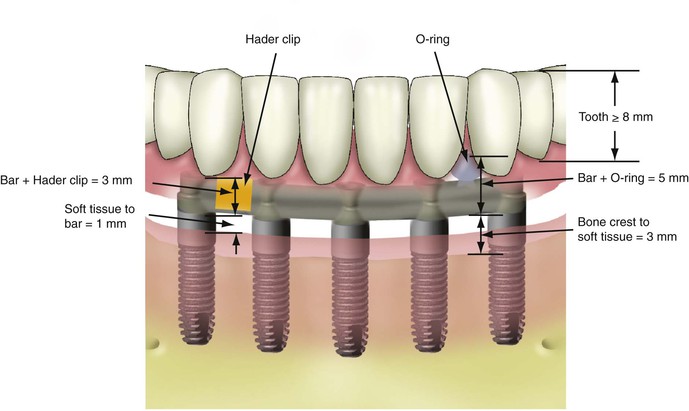

The mandible bone may also be a disadvantage for an IOD. The mandibular overdenture treatment plan requires more than 12 mm of space between crestal bone and the occlusal plane (Figure 23-7). When sufficient crown height space (CHS) is lacking, the prosthesis is more prone to component fatigue and fracture and has more complications than porcelain-to-metal fixed prostheses. The 12-mm minimum CHS provides adequate bulk of acrylic to resist fracture; space to set denture teeth without modification; and room for attachments, bars, soft tissue, and hygiene. In the mandible, the soft tissue is often 1 to 3 mm thick above the bone, so the occlusal plane to soft tissue should be at least 10 mm in height. An osteoplasty to increase CHS before implant placement is often indicated, especially when abundant bone height and width are present (Figure 23-8). Otherwise, a fixed porcelain–metal restoration should be considered.

Another complication related to the available bone is inclination or angulation of the mandible, especially when the alveolar process has resorbed. The division C–a anterior mandible is angled more than 30 degrees. If the surgeon is unaware of this angulation, the implants may perforate the lingual plate and irritate the tissues of the floor of the mouth (Figure 23-9). If the surgeon places the implants within the bone, they may enter the crest of the ridge at the floor of the mouth and make it almost impossible to restore (Figure 23-10). In a study by Quirynen et al. of 210 computer tomogram images, 28% of the anterior mandibles were lingually tilted −67.6 degrees ± 5.5 degrees.7 The mandibles with less than −60 degree tilt represent about 5% of the cases.

Although the initial cost of treatment may be less for an IOD, overdenture wearers often incur greater long-term expenses than those with fixed restorations. Attachments (such as O-rings or clips) regularly wear and must be replaced. Replacements appear more frequent during the first year but remain a necessary maintenance step.18,21,35,69–76 In a study by Bilhan et al. on 59 patients, two thirds of IOD patients had prosthetic-related complications the first year.77 For example, relines were necessary in 16%, loss of retention in 10.2%, fracture of the IOD in 8.5%, pressure spots in 8.5%, dislodged attachment in 6.8%, and screw loosening in 3.4%.

Denture teeth wear faster on an IOD than with a traditional denture because bite force and masticatory dynamics are improved. A new overdenture often is required at 5- to 7-year increments because of denture tooth wear and changes in the soft tissue support. Therefore, patient education of the long-term maintenance requirement should be outlined at the onset of implant therapy.57

A side effect of a mandibular IOD is food impaction. The flanges of the prosthesis do not extend to the floor of the mouth in the rest position (to eliminate sore spots caused by elevation of the floor of the mouth during swallowing). However, during eating, food particles migrate and become impacted under the prosthesis during swallowing. A similar condition is found with a traditional denture. However, because a lower denture “floats” during function, the food more readily goes under and then through, but the IOD traps the food debris against the implants, bars, and attachments (Box 23-3).

Review of the Literature

The concept of mandibular implant–supported overdentures has been used for many years. Successful reports were published originally with mandibular subperiostal implants or with immediately loaded and stabilized root form implants in the anterior mandible more than 4 decades ago.1,2

In 1986, a multicenter study reported on 1739 implants placed in the mandibular symphysis of 484 patients.2 The implants were loaded immediately and restored with bars and IOD with clips as retention. The overall implant success rate was 94%. Engquist et al.3 reported a 6% to 7% implant failure for mandibular implant–supported overdentures in 1988. Jemt et al.4 reported on a 5-year prospective, multicenter study on 30 maxillae (117 Brånemark implants) and 103 mandibles with 393 implants. Survival rates in the mandible were 94.5% for implants and 100% for prostheses.4 Attard and Zarb followed IOD wearers for 20 years with a success rate of 84% and 87% for prosthesis and implants, respectively.35

More recent studies demonstrate even greater implant success rates when used to support a mandibular overdenture. A review of implant literature by Goodacre et al. in 2003 found mandibular implant overdentures have higher implant survival rates compared with any other type of implant prosthesis.78 Wismeijer et al.5 reported on 64 patients with 218 titanium plasma-sprayed implants with a 97% survival with overdentures in a 6.5-year evaluation. Naert et al.15 found 100% implant success at 5 years for mandibular overdentures with different anchorage systems. In Belgium, Naert at al. reported on 207 consecutively treated patients with 449 Brånemark implants and Dolder-bar mandibular overdentures. In this report, the cumulative implant failure rate was only 3% at the 10-year benchmark.9,10 Similarly, Hutton et al.12 reported 97% survival rates for mandibular overdentures.

Misch13 reported less than 1% implant failure and no prosthesis failure over a 7-year period with 147 mandibular overdentures (IOD) when using the organized treatment options and prosthetic guidelines presented in this chapter. Kline et al. reported on 266 mandibular implant–supported overdentures for 51 patients, with an implant survival rate of 99.6% and a prosthesis survival rate of 100%.79 Mericke-Stern et al. reported 95% implant survival with two implant overdentures in the mandible. In a 10-year study of IODs in Israel, with 285 implants and 69 implant overdentures, Schwartz-Arad et al. reported implant survival was 96.1% with higher success rates in the mandible.42

In conclusion, many reports have been published over the past 2 decades that conclude that mandibular implant–supported overdentures represent a predictable option for denture wearers.

Overdenture Treatment Options

Traditional overdentures must rely on the remaining teeth to support the prosthesis. The location of these natural abutments is highly variable, and they often comprise past bone loss associated with periodontal disease. For a mandibular implant–supported overdenture, the implants may be placed in planned, specific sites, and their number may be determined by the restoring doctor and patient. In addition, the overdenture implant abutments are healthy and rigid and provide an excellent support system. As a result, the related benefits and risks of each treatment option may be predetermined.

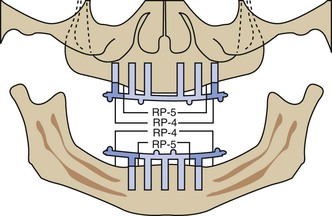

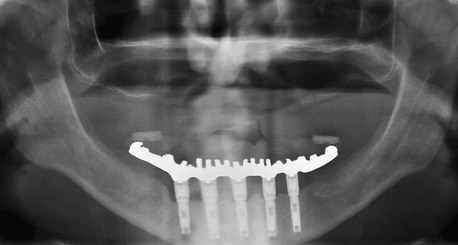

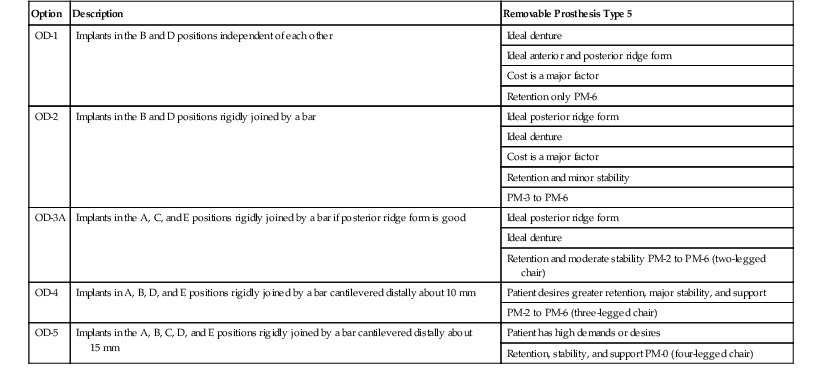

In 1985, the author presented five organized treatment options for implant-supported mandibular overdentures in completely edentulous patients.13,80,81 The treatment options range from primarily soft tissue support and implant retention (RP-5) to a completely implant-supported prosthesis (RP-4) with rigid stability (Table 23-1). The prostheses are supported by two to five anterior implants for these options. The four RP-5 options have a range of retention, support, and stability. The RP-4 restoration has a rigid cantileverd bar that completely supports, stabilizes, and retains the restoration (Figure 23-11).

TABLE 23-1

Mandibular Overdenture Treatment Options

| Option | Description | Removable Prosthesis Type 5 |

| OD-1 | Implants in the B and D positions independent of each other | Ideal denture |

| Ideal anterior and posterior ridge form | ||

| Cost is a major factor | ||

| Retention only PM-6 | ||

| OD-2 | Implants in the B and D positions rigidly joined by a bar | Ideal posterior ridge form |

| Ideal denture | ||

| Cost is a major factor | ||

| Retention and minor stability | ||

| PM-3 to PM-6 | ||

| OD-3A | Implants in the A, C, and E positions rigidly joined by a bar if posterior ridge form is good | Ideal posterior ridge form |

| Ideal denture | ||

| Retention and moderate stability PM-2 to PM-6 (two-legged chair) | ||

| OD-4 | Implants in A, B, D, and E positions rigidly joined by a bar cantilevered distally about 10 mm | Patient desires greater retention, major stability, and support |

| PM-2 to PM-6 (three-legged chair) | ||

| OD-5 | Implants in the A, B, C, D, and E positions rigidly joined by a bar cantilevered distally about 15 mm | Patient has high demands or desires |

| Retention, stability, and support PM-0 (four-legged chair) |

OD, Overdenture option; PM, prosthesis movement class.

From Misch CE: Misch Implant Institute manual, Dearborn, MI, 1984, Misch International Implant Institute.

The overdenture options err on the side of safety to reduce the risk of failure and complications of bone loss and superstructure loosening. The initial treatment options are presented for completely edentulous patients with division A (abundant) or B (sufficient) anterior bone treated with division A anterior root form implants of 4 mm or greater diameter. Modifications related to posterior ridge support and arch form also are discussed. Following these standardized conditions, anterior bone volume conditions of moderate atrophy (division C minus height [C–h]) are presented.

Overdenture Movement

To develop a treatment plan for a mandibular IOD, the final prosthesis should be determined related to the necessary retention, support, and stability required for the restoration. Retention of the restoration is related to vertical force necessary to dislodge the prosthesis. Support is related to the amount of vertical movement of the prosthesis toward the tissue. Stability of a prosthesis is evaluated with horizontal or cantilevered forces applied to the restoration. The amount of retention is related to the number and type of overdenture attachments. The stability of the IOD is more related to implant (and bar) position, and support is primarily related to implant number (and bar design in the posterior region). The patient’s complaints, anatomy, desires, and financial commitment determine the amount of implant support, retention, and stability required to predictably address these conditions. Because different anatomic conditions and patient force factors influence these factors for an IOD, not all prostheses should be treated in the same manner. In other words, a two-implant overdenture should not be the only treatment plan offered to a patient. One should emphasize that most mandibular overdentures should be designed to eventually result in a RP-4 prosthesis, as previously discussed.

The most common complications found with mandibular implant overdentures are related to prosthetics and an understanding of retention, support, and stability of the prosthesis. For example, when a fixed restoration is fabricated on implants, it is rigid, and cantilevers or offset loads are clearly identified. Rarely will a practitioner place a full-arch fixed restoration on three implants, especially with excessive cantilevers because of implant positioning. However, three anterior implants with a connecting bar may support a completely fixed overdenture, solely because of attachment design or placement. The restoring doctor thinks the three-implant overdenture has less implant support but does not realize that an overdenture that does not move during function is actually a fixed restoration. Therefore, an overdenture with no prosthesis movement (PM) should be supported by the same number, position, and design of implants as a fixed restoration.

Many precision attachments with varying ranges of motion are used in implant overdentures. The motion may occur in zero (rigid) to six directions or planes: occlusal, gingival, facial, lingual, mesial, and distal. A type 2 attachment moves in two planes and a type 4 attachment in four planes. An IOD may also have a range of movement during function. It should be understood that the resulting overdenture movement during function may be completely different from the one provided by independent attachments and may vary from zero to six directions depending on the position and number of attachments, even when using the same attachment type. For example, an “O” ring attachment may allow six directions of movement. However, when four “O” rings are placed on a bar, the prosthesis movement (PM) during function or parafunction may have no directions of movements (Figure 23-12). Therefore, attachment and PM are independent from each other and should be evaluated as such. An important item for the IOD treatment plan is to consider how much PM the patient can adapt to or tolerate on the final restoration.

Classification of Prosthesis Movement

The classification system proposed by the author in 1985 evaluates the directions of movement of the implant-supported prosthesis, not the overall range of motion for the individual attachment; therefore, the amount of PM is the primary concern. An overdenture is by definition removable, but in function or parafunction, the prosthesis may not move. If the prosthesis does not have movement during function, it is designated PM-0 and requires implant support similar to a fixed prosthesis. A prosthesis with a hinge motion is PM-2, and a prosthesis with an apical and hinge motion is PM-3. A PM-4 allows movement in four directions, and a PM-6 has ranges of PM in all directions.

Prosthesis Movement

The dentist determines the amount of PM the patient desires or the anatomy may tolerate. If the prosthesis is rigid when in place but can be removed, the PM is labeled PM-0 regardless of the attachments used. For example, O-rings may provide motion in six different directions. But if four O-rings are placed along a complete arch bar and the prosthesis rests on the bar, the situation may result in a PM-0 restoration. A hingelike PM permits movement in two planes (PM-2) and most often uses a hingelike attachment. For example, the Dolder bar and clip without a spacer or Hader bar and clip are the most commonly used hingelike attachments. A Dolder bar is egg shaped in cross-section, and a Hader bar is round. A clip attachment may rotate directly on the Dolder bar. A Hader bar is more flexible because round bars flex to the power of 4 related to the distance and other bar shapes flex to the power of 3. As a result, an apron often is added to the tissue side of the Hader bar to limit metal flexure, which might contribute to unretained abutments or bar fracture. A cross-section of the Hader bar and clip system reveals that the apron, by which the system gains strength compared with a round bar design, also limits the amplitude of rotation of the clip (and prosthesis) around the fulcrum to 20 degrees, thus transforming the prosthesis and bar into a more rigid assembly (Figure 23-13). Therefore, the Hader bar and clip system may be used for a PM-2 when posterior ridge shapes are favorabl/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses