Chapter 23

Nasal reconstruction

Introduction

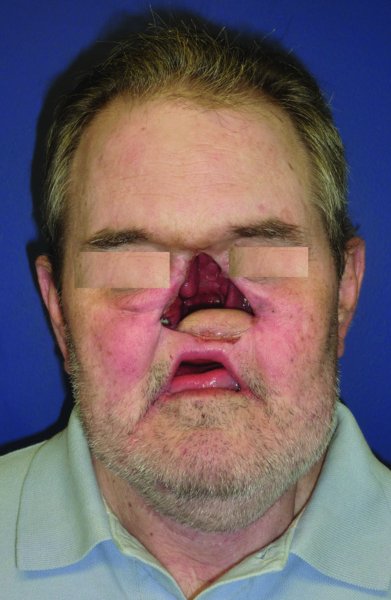

The nose takes on a prominent role in our face and is one of the principle contributors to our facial appearance. Aside from its role in facial appearance, the nose also serves an important functional role in filtering and humidifying the air that we breathe. Given its role as both a functional and esthetic unit, defects of the nose have the potential to affect both our respiratory function as well as our psyche (Figure 23.1).

Figure 23.1 View of a patient post rhinectomy with reconstruction of the oral nasal defect with a free tissue transfer.

The reconstruction of nasal defects dates back several hundred years to the Indian continent. Various methods are available to reconstruct nasal defects. The option for which flap or technique to use will be directly related to the size and composition of the defect. The focus of the nasal defect evaluation should not be simply a determination of size, it should be an evaluation of the layers of tissues that are missing. The assessment of the missing tissue should determine the status of the nasal lining, the structural support (i.e., the cartilage), and finally, the skin component.

Anatomy

The external nasal anatomy can be approached based on the subunit analysis as was described by Gonzales-Ulloa in 1957.1 Many years later, in 1985, Burget and Menick further developed this concept, focusing on nasal reconstruction.2 In their manuscript, they divided the nose into six subunits and advocated the excision of the entire subunit in order to achieve the best esthetic result. The nose was divided into the following subunits: dorsal subunit, the nasal sidewalls, the soft triangle, the ala, the columella, and the nasal tip. The nasal sidewalls, ala, and soft triangle are paired subunits; when this is taken into account, the nose can be subdivided into 9 subunits.

The bony and cartilaginous framework of the nose provides the support for the nasal cover and its arrangement is reflected in the contour of the skin.3 The structural composition of the nose is made up by the nasal bone, which extends from the nasofrontal suture until it meets the upper lateral cartilage. Extending caudally from the upper lateral cartilage is the lower lateral cartilage (alar cartilage).

The midline support is formed by the bony and cartilaginous septum. The bony component is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the vomer.

The blood supply to the nose is formed by the contribution of both the internal as well as the external carotid system. The nasal sidewalls and dorsum are supplied by the dorsal nasal and angular branches of the ophthalmic artery as well as the infraorbital artery, a branch of the maxillary artery. The nasal cavity is supplied by the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, the sphenopalatine artery, and the septal branch from the superior labial artery.

Defect assessment

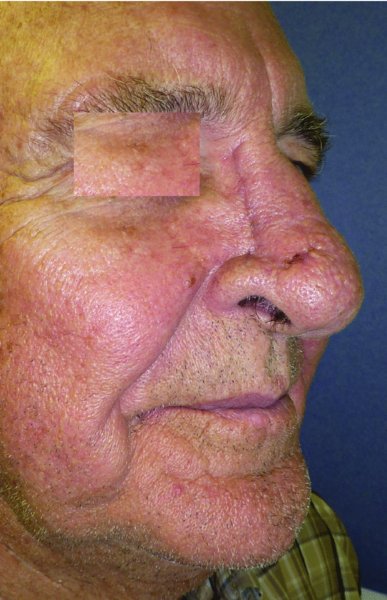

Nasal defects are most often encountered due to excision of either benign or malignant tumors. Other causes of nasal defects are traumatic and due to degenerative diseases such as Wegner’s granulomatosis. Traumatic defects can present secondary to motor vehicle collisions, interpersonal violence (Figure 23.2), and animal bites (Figure 23.3). The major difference between defects resulting from trauma vs. tumor excision is the ability to design and plan the defect.

Figure 23.2 View of a horrific defect secondary to a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the face.

Figure 23.3 View of a nasal defect after avulsive injury from a dog bite.

Menick advocates that the reconstructive surgeon ask the following set of questions: What is missing anatomically? What is missing esthetically (e.g., the facial landmarks, practically described as regional subunits)? Is the underlying disease process controlled? Are donor sites available or depleted or devascularized by prior injury or surgery? Does the patient’s health limit surgical stages, anesthesia, materials, or techniques?4

Once the defect is analyzed, whenever possible the surgeon should utilize the intact contralateral subunit to make a precise template which can be transferred to the defect site and, if needed, the remainder of the affected subunit can be excised. The use of the contralateral intact subunit gives a more precise reconstruction.

Site and size oriented approach to reconstruction

As previously stated, the location of the defect is only one of the considerations for nasal reconstruction. The surgeon should critically assess the composition of the defect as it will play a critical factor in the choice of reconstruction. The complexity of the reconstruction increases with the layers involved in the resection. Defects affecting the skin will be easier to reconstruct compared to those involving the skin and underlying cartilage and that in turn is easier than defects affection all the layers.

Resurfacing the nose

Small defects

Small size defects may occur in any of the subsites of the nose. The location of the defect will often dictate the choice of reconstruction. Defects measuring less than 1.5 cm can be reconstructed with a variety of techniques ranging from healing by secondary intention, full thickness skin grafts (Figure 23.4), or various local tissue transpositions (Figures 23.5 to 23.10).

Figure 23.4 Appearance of a full-thickness skin graft to the nasal defect.

Figure 23.5 Defect of the lateral nasal wall with markings for a repair with a sliding nasal flap.

Figure 23.6 Incision of the nasal flap prior to advancement.

Figure 23.7 Elevation and undermining of the flap.

Figure 23.8 Confirmation of the passive reach of the sliding nasal flap.

Figure 23.9 Primary repair of the defect with the sliding flap.

Figure 23.10 Early postoperative appearance of the nasal reconstruction.

23.5.2 Medium defects

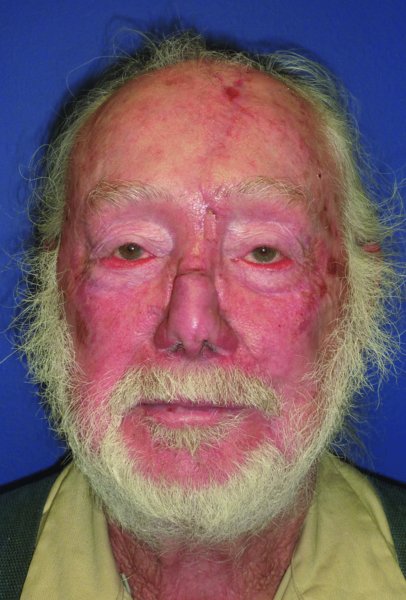

Larger defects will typically extend beyond a single subunit to encompass multiple subunits. The approach to these defects should be made with the final appearance in mind. A commonly accepted approach has been to examine the involved units and to carry out a complete subunit excision where the defect is greater than 50% of the subunit. Although this approach will result in a greater soft tissue defect, the resurfacing of the nose with a single flap gives a better final outcome of the reconstruction. When resurfacing a larger area of the nose, the most commonly utilized flap is the paramedian forehead flap. The flap, as described previously, allows small defects to be resurfaced in areas such as the ala as well as resurfacing of the entire nose. An example of the need to resurface several subunits can be seen in the case of an 80-year-old Caucasian male who was referred for reconstruction of two neglected squamous cell carcinomas of the face, one located on the nose and the other on the left face (Figure 23.11). The resection of the nasal lesion resulted in a large defect (Figure 23.12). The paramedian forehead flap was utilized to resurface the nose as a two-stage procedure (Figures 23.13 to 23.15). The final appearance after takedown of the pedicle was acceptable to the patient and he declined any further revisions (Figure 23.16).

Figure 23.11 Appearance of a patient with markings for resection of a large nasal lesion as well as a cheek lesion.

Figure 23.12 Defect after complex resection and frozen section assessment; markings for a paramedian flap reconstruction.

Figure 23.13 Elevated paramedian flap prior to transfer.

Figure 23.14 Inset of the paramedian forehead flap.

Figure 23.15 Early postoperative view of the reconstructed nasal defect with the paramedian flap prior to second stage.

Figure 23.16 Early view of the final nasal reconstruction without any re/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses