chapter 23 Anatomy for Venipuncture

Venipuncture is not a difficult technique to learn. Indeed, Malamed demonstrated that the initial attempt at venipuncture by untrained dental students had a greater than 90% success rate.1 However, proficiency requires practice. Once learned, knowledge of the technique remains with the dentist forever; yet because it is an acquired skill, if not used regularly, the level of the dentist’s ability will diminish.

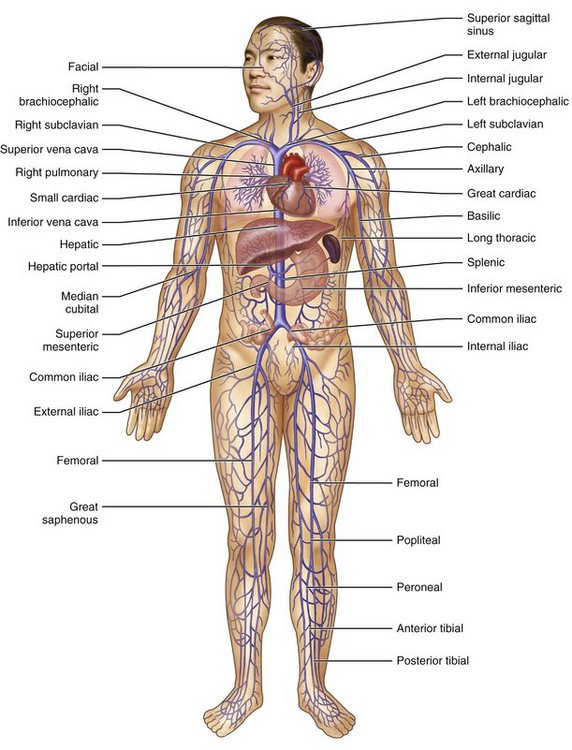

In theory, venipuncture may be attempted in any superficial vein of a size sufficient to accommodate the needle. Figure 23-1 illustrates the major superficial veins in the human body. In practice, however, elective venipuncture is usually confined to one of the patient’s extremities. Either an arm or leg may be used. The usual preference is the arm, with the leg used when arm veins are inadequate or in emergency situations in which the arm may be unavailable or unsuitable for use.

ARTERIES OF THE UPPER LIMB

Blood to the right upper limb leaves the aortic arch through the short, wide brachiocephalic (innominate) trunk, which divides into the right common carotid and right subclavian arteries, the latter delivering arterial blood to the upper limb. On the left side, the subclavian artery is a direct branch of the arch of the aorta. From this point onward, the arteries of the two sides are symmetric.2

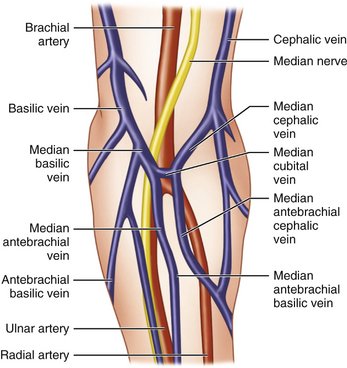

At the outer border of the first rib, the subclavian artery turns laterally to enter into the axilla. At this point, it is termed the axillary artery. The axillary artery leaves the axilla at the lower border of the teres major muscle to enter the arm or brachium as the brachial artery. Approximately 1 inch below the antecubital fossa, the brachial artery bifurcates into the radial and ulnar arteries (Figure 23-2), which travel distally in the forearm and terminate in the palm as an arterial arch. The ulnar artery forms the superficial palmar arch, which travels to the level of the web of the thumb, where it is completed by a small branch arising from the radial artery, the superficial palmar branch. The radial artery crosses the bottom of the so-called snuffbox (the hollow at the base of the thumb), reaching the dorsum of the hand and then entering the palm. There it forms the deep palmar arch, which is completed by a small branch from the ulnar artery, the deep palmar branch.

VEINS OF THE UPPER LIMB

Slots are an essential part of orthodontic treatment, allowing wires to be secured to braces and guiding teeth into proper alignment. These small channels in the brackets are carefully designed to hold the wire in place while still allowing for necessary adjustments.The superficial veins of the upper limb are the veins selected for most elective venipuncture. Their anatomy is discussed in the following sections (see Figure 23-1).

ANATOMY

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses