Chapter 22

Lip reconstruction

Introduction

The lips along with the eyes are the two most expressive structures in our face. The lips are able to convey a myriad of minute expressions and emotions. Additionally, the lips are critical in eating and speaking. Because of its role, the need to properly repair lip defects is very important to the reconstructive surgeon. The challenge increases proportionally with the size and location of the defect. Over the years, many surgeons have tackled this challenge with numerous approaches.

The most commonly encountered lip defects are those resulting from excision of lesions affecting the lower lip. Because of the lower lips’ prominence and exposure to sunlight, it is affected nearly nine times more than the upper lip. Conversely, traumatic defects occur more often in the upper lip. This is particularly more so in bite incidences.

Traditionally, the approaches to reconstruction of lip defects have followed a simple algorithm of defect size. This approach takes into account the differences in shape, size, and pliability of the lower lip compared to the upper lip. When using the traditional approach, defects of the lower lip less than one-third of the total lip size can be repaired by primary closure. Defects greater than one-third but less than two-thirds can be reconstructed with a variety of local flap techniques. Defects greater than to two-thirds or total lip defects are often addressed with free tissue transfer. A similar approach can be used for upper lip defects with a simple caveat that smaller defects can be closed primarily; this percentage is usually around 25% of the upper lip.

Anatomy

The surface anatomy of the upper and lower lip are different. The upper lip is divided into four subunits: the central philtral, the two lateral units, and the mucosal subunit. The lateral units extend lateral to the philtral column and medial to the melolabial fold. The surface anatomy of the lower lip is composed of two subunits: the mucosal and the central.

The lip is composed of a circular muscle, the orbicularis oris, which forms the oral sphincter. The orbicularis is responsible for maintaining oral competence and seal. Attached to the orbicularis, the levators and depressors of the lips are entrusted with the fine movements of the lip and for helping to convey many of our emotions through facial expressions emanating from this area. The lateral condensation of these muscles forms the modiolus.

The inner aspect of the orbicularis muscle is lined by the oral mucosa while the skin covers the muscle. Interposed between the muscle and the mucosa are numerous minor salivary glands. The vermillion is the mucosal extension from the inner lip extending to the external aspect to meet the skin and form the vermillion cutaneous junction often referred to as the white line or white roll.

The blood supply to the lip emerges from the facial artery as it travels superiorly over the mandible towards the lip and gives off a branch to perfuse the lower lip. This branch is the inferior labial artery. The facial artery continues its superior migration lateral to the modiolus, and gives off another branch that travels medially to perfuse the upper lip. This branch is the superior labial artery. Veins bearing the same name and travelling alongside the arteries supply the venous drainage to the upper and lower lips.

The lips receive motor innervation from branches of the seventh cranial nerve. The buccal branches innervate the upper lip while the lower lip is innervated by the marginal mandibular branches. The sensory innervation is supplied by the fifth cranial nerve. The upper lip is supplied by the second division while the lower lip is supplied by the third division.

Defect assessment

Upper lip defects

Defects less than 25%

Small defects of the upper lip can be readily addressed by ensuring freshening of the lateral borders of the defect (in traumatic cases) and reapproximation of the mucosa, muscular, and skin layers. The outcome of these defects is often pleasing without much evidence of the surgical intervention.

Defects greater than 25%

Abbe flap

In cases where the defect size is greater than what could be closed with a simple advancement and closure, an Abbe flap may be used to repair the defect. The initial description of the Abbe flap is attributed to Dr. Robert Abbe based on his publication in 1898.1 Recent attention has been given to the accuracy of this attribution; some authors feel that the procedure had been previously described, albeit in different language2,3.

The flap is designed by borrowing a composite from the lower lip and transferring it to the upper lip. This is carried out in stages. The initial assessment is made after removing the lesion from the upper lip and then assessing the width and height of the defect (Figures 22.1 to 22.3). The defect measurement or template is then transferred to the lower lip. The width of the flap should be less than that of the defect (about half) while the height should remain the same (Figure 22.4). A decision should be made as to what side the flap should be pedicled from, this is done from the side that would allow easiest of transfer to the defect without kinking the pedicle and compromising the flap (Figure 22.5). The flap is then rotated to the defect (Figure 22.6). The inset should be done with care to reapproximate each of the three layers, i.e. the mucosa, the orbicularis, and the skin. Particular attention should be taken to the reapproximation of the white roll from the flap and each recipient side (Figure 22.7). The flap is allowed to heal for 2 to 3 weeks. During this time period, the flap will develop enough collateral flow that will allow for the takedown of the flap and ligation of the inferior labial artery (Figures 22.8 and 22.9). The adequacy of the collateral blood flow to the flap can be assessed prior to separation of the flap by ligating the pedicle with a rubber band and evaluating the flap for perfusion and congestion (Figure 22.10). Once the perfusion is determined to be adequate, the flap is separated and the mucosa and superior aspects of the muscle are reapproximated to establish a normal lip contour (Figure 22.11).

Figure 22.1 View of a patient with an upper lip carcinoma with markings made for the resection.

Figure 22.2 Incision of the lesion.

Figure 22.3 View of the resection and area to be reconstructed.

Figure 22.4 Markings for a transposition flap in the form of an Abbe flap.

Figure 22.5 Incision of the Abbe flap with the pedicle located on the upper left portion of the lip.

Figure 22.6 Rotation of the Abbe flap prior to inset.

Figure 22.7 Inset of the flap with the pedicle coming in from the lower lip.

Figure 22.8 Appearance of the reconstructed lip prior to takedown of the pedicle.

Figure 22.9 View of the pedicle prior to resection.

Figure 22.10 Assessment of perfusion of the flap from the collateral supply by occlusion of the pedicle.

Figure 22.11 Appearance of the final reconstruction.

V–Y advancement flap

The V–Y technique is described in Chapter 8. The technique can be used throughout the head and neck. In the reconstruction of upper lip it can be used in conjunction with other local flaps to repair very large defects. The patient in this example was referred from a mental institution for evaluation of a longstanding basal cell carcinoma of the left upper lip with extension to the cheek (Figure 22.12). The lesion was marked for resection with the anticipation of reconstructing the defect with local tissue (Figure 22.13). The defect was found to extend to the cheek and encompass nearly half of the upper lip (Figure 22.14). A combination of a V–Y flap based on the perforators from the facial artery and a cheek advancement flap was planned (Figure 22.15. The flap was elevated and mobilized while taking care not to injure the perforators to the skin flap (Figures 22.16 to 22.18). The flap was then mobilized along with a perialar crescentic flap from the contralateral side and the cheek advancement flap from the ipsilateral side to repair the defect with minimal distortion (Figures 22.19 and 22.20).

Figure 22.12 View of a patient with a large neglected malignancy on the left upper lip extending to the cheek.

Figure 22.13 Outline for the planned resection; note the very large outline.

Figure 22.14 View of the defect with greater than half of the upper lip missing as well as a large portion of the cheek.

Figure 22.15 Plan for the use of a facial artery perforator flap and a cheek advancement.

Figure 22.16 Incision of the planned flap prior to transfer.

Figure 22.17 Assessment of the advancement of the flap into the defect.

Figure 22.18 View of the underside of the flap where the perforators are gaining access to the flap.

Figure 22.19 Advancement and inset of the facial perforator flap and cheek advancement. Note that there is no distortion of the lip in this very large repair.

Figure 22.20 Lateral view of the reconstruction.

The final appearance of the patient was acceptable overall (Figure 22.21). This case illustrates the use of combining the V–Y flap with other techniques to repair very large upper lip defects.

Figure 22.21 Postoperative view of the reconstructed lip again showing little deformation of the upper lip.

Perialar crescentic flap

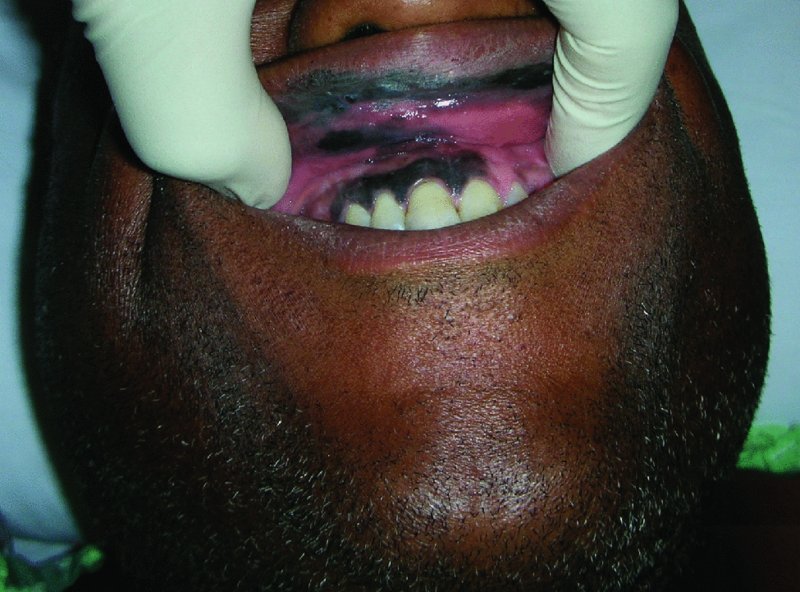

The perialar crescentic flap allows for the reconstruction of upper lip defects by mobilizing the tissues inward towards the defect. The perialar crescentic flap can be used in combination with another flap in order to repair large defects of the upper lip. The following case illustrates the use of such a combination. The patient was diagnosed with a mucosal melanoma of the upper lip, which extended towards the gingiva of the anterior maxilla (Figure 22.22). The anticipated defect would require a combination of flaps to restore the oral sphincter. The planned excision involved a near total upper lip resection and an anterior maxillectomy. The planned reconstruction was for bilateral perialar crescentic flap advancement and an Abbe transfer from the central lower lip (Figure 22.23). The resection of the upper lip and anterior maxilla was carried out as planned (Figures 22.24, 22.25, and 22.26a–c). The markings for the perialar crescentic flap were made in order to decrease the defect to about half of its original size (Figure 22.27). The skin excision was performed allowing for the advancement of the flap (Figures 22.28 and 22.29). With the size of the defect reduced to nearly 50% of its original size, the Abbe flap was marked, elevated, and transferred to repair the defect (Figure 22.30). The patient did well from the reconstruction.

Figure 22.22 View of/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses